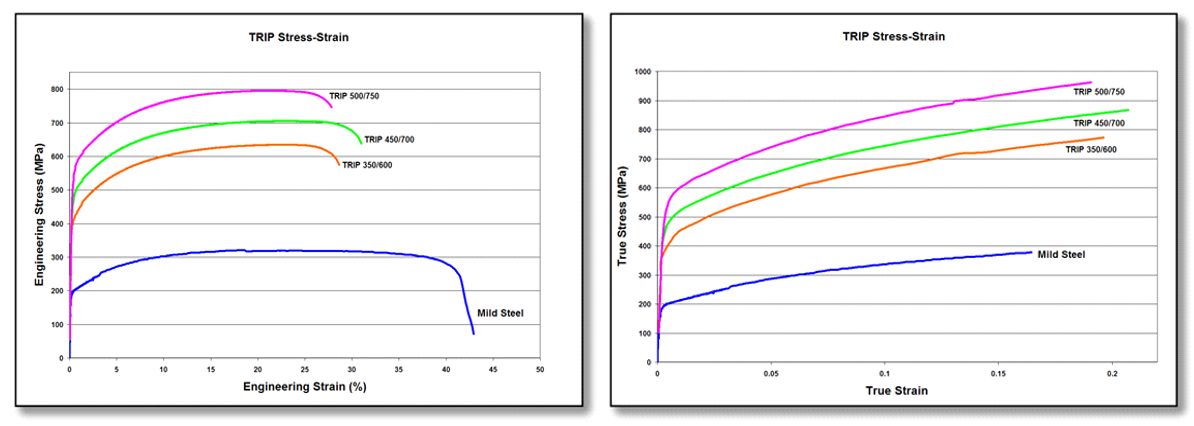

| Tensile Testing: Engineering Stress-Strain Curves vs. True Stress-Strain Curves | Advanced High-Strength Steels, AHSS, engineering stress, Engineering Stress-Strain Curve, tensile, tensile testing, True Stress-Strain Curve | AHSS, Blog, homepage-featured-top, main-blog, Mechanical Properties | advanced-high-strength-steels ahss engineering-stress engineering-stress-strain-curve tensile tensile-testing true-stress-strain-curve | ahss blog homepage-featured-top main-blog mechanical-properties steel-grades metallurgy forming |

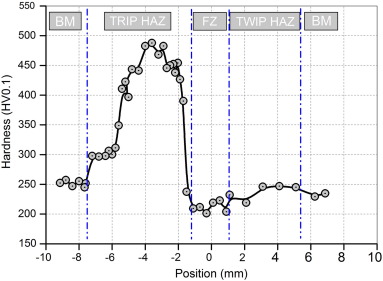

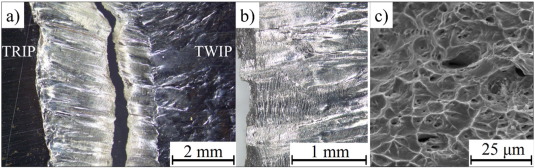

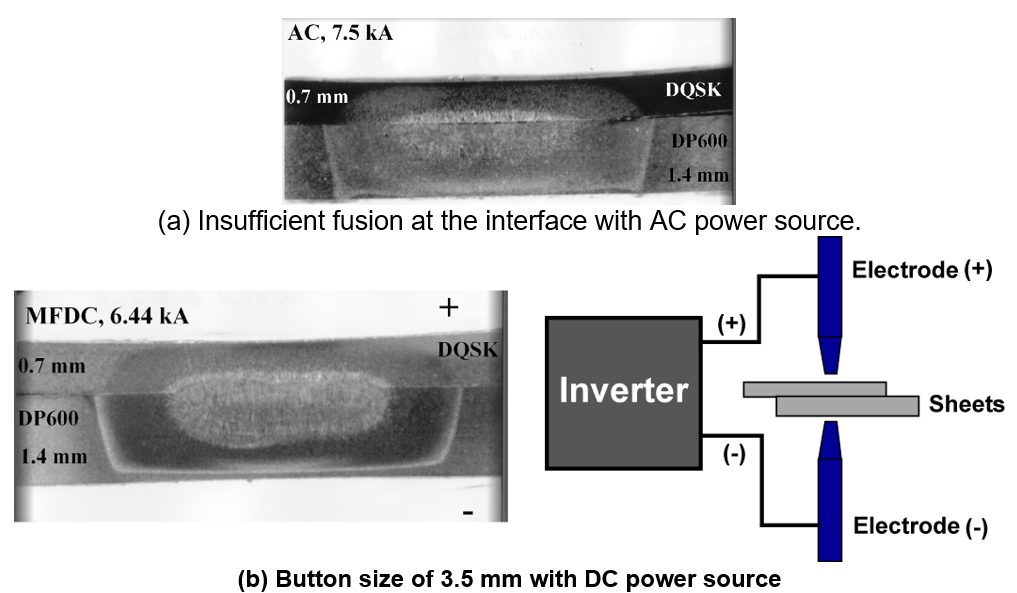

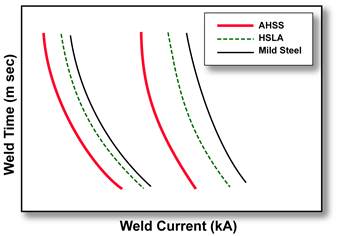

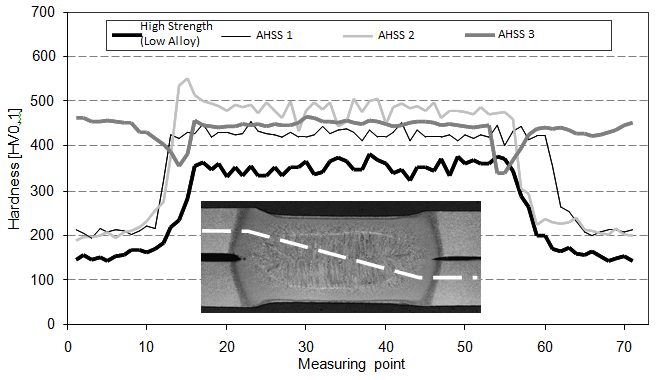

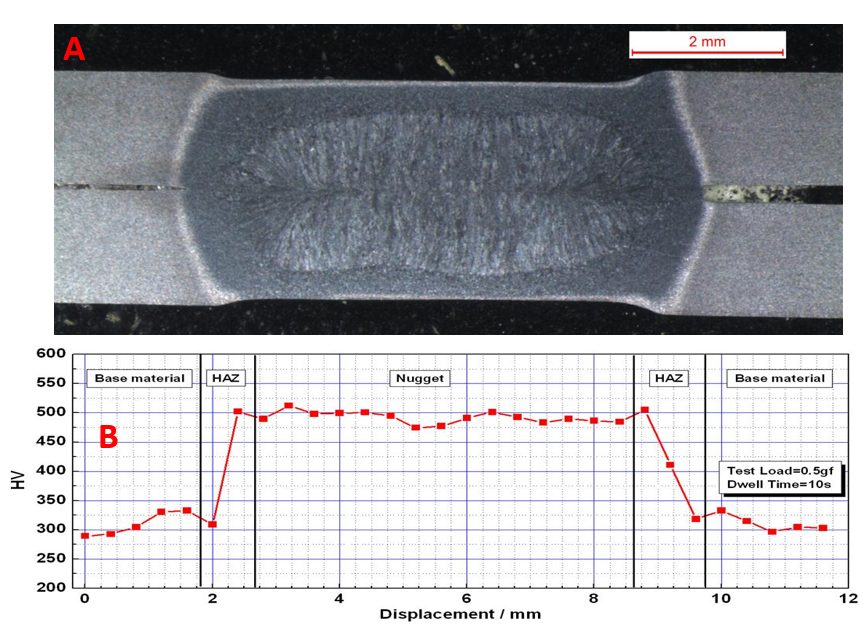

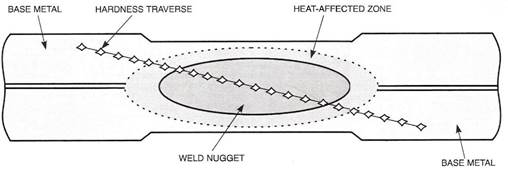

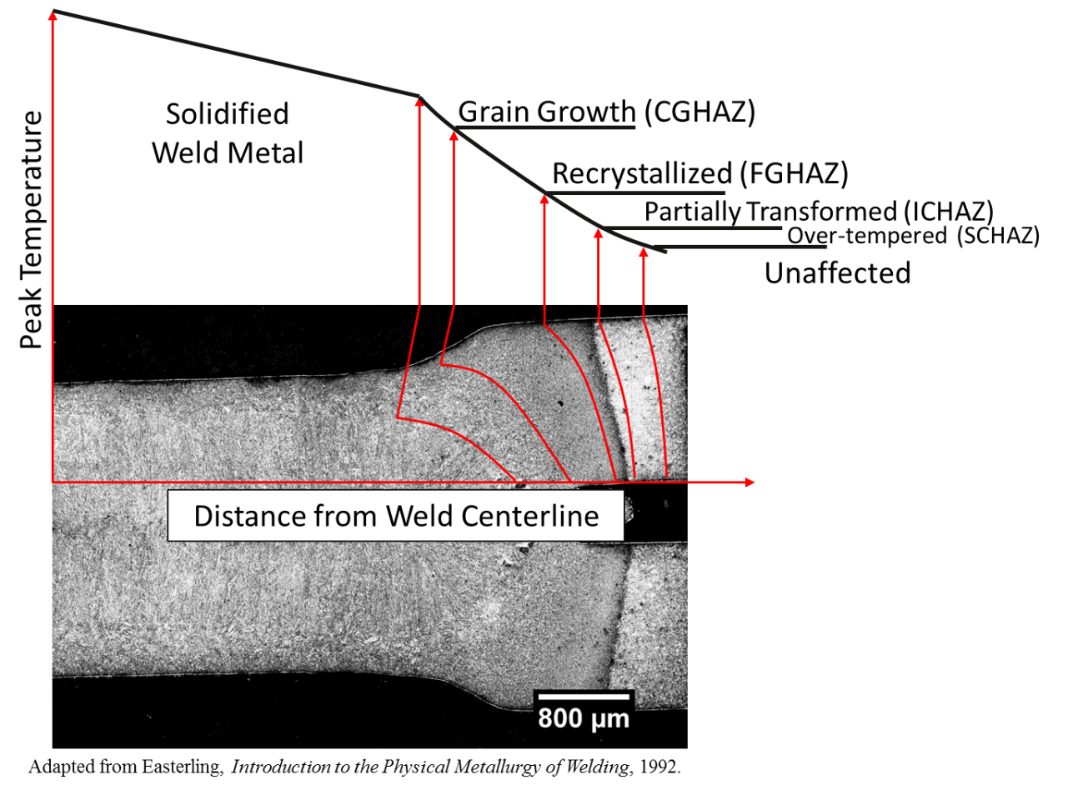

| Resistance Spot Welding with Advanced High-Strength Steels: Cold Stamped and Hot Formed | Advanced High-Strength Steels, AHSS, M. Kimchi, resistance spot welding, RSW, RSW procedures | AHSS, Blog, homepage-featured-top, Joining, Joining Dissimilar Materials, main-blog, Steel Grades | advanced-high-strength-steels ahss m-kimchi resistance-spot-welding rsw rsw-procedures | ahss blog homepage-featured-top joining joining-dissimilar-materials main-blog steel-grades metallurgy |

| Steel E-Motive AHSS Body Concept Demonstrates Benefits Of Part Integration | | AHSS, Blog, homepage-featured-top, main-blog, News | | ahss blog homepage-featured-top main-blog news steel-grades metallurgy |

| How Steel Properties Influence the Roll Forming Process | | 3rdGen AHSS, AHSS, Blog, Forming, main-blog, News, Press Hardened Steels, Roll Forming, Roll Stamping, Springback, Steel Grades | | 3rdgen-ahss ahss blog forming main-blog news press-hardened-steels roll-forming roll-stamping springback steel-grades metallurgy |

| Resistance Spot Welding: 5T Dissimilar Steel Stack-ups for Automotive Applications | 5T stack ups, AHSS, resistance spot welding, RSW, RSW parameters, RSW procedures, stack ups | AHSS, Blog, homepage-featured-top, Joining, main-blog, News, Resistance Spot Welding, RSW of Dissimilar Steel, Steel Grades, Tool & Die Professionals | 5t-stack-ups ahss resistance-spot-welding rsw rsw-parameters rsw-procedures stack-ups | ahss blog homepage-featured-top joining main-blog news resistance-spot-welding rsw-of-dissimilar-steel steel-grades tool-die-professionals metallurgy resistance-welding-processes |

| Stronger AHSS Knowledge Required for Metal Stampers | AHSS, Coil Processing, heat treatment, metal stamping, Tooling | 1stGen AHSS, 2ndGen AHSS, 3rdGen AHSS, AHSS, Blog, homepage-featured-top, main-blog, News, Production Managers, Steel Grades, Tool & Die Professionals | ahss coil-processing heat-treatment metal-stamping tooling | 1stgen-ahss 2ndgen-ahss 3rdgen-ahss ahss blog homepage-featured-top main-blog news production-managers steel-grades tool-die-professionals metallurgy |

| Steel E-Motive: A Future Mobility Concept Paving the Way to Net Zero Emissions | battery electric vehicles, electric vehicles, future mobility, Level 5 autonomy, steel e-motive | AHSS, Blog, main-blog, News | battery-electric-vehicles electric-vehicles future-mobility level-5-autonomy steel-e-motive | ahss blog main-blog news steel-grades metallurgy |

| Steel E-Motive: Autonomous Vehicles That Only Steel Can Make Real | Advanced High-Strength Steels, AHSS, Steel EMotive | 3rdGen AHSS, AHSS, Blog, General, main-blog, Metallurgy, News, Steel Grades | advanced-high-strength-steels ahss steel-emotive | 3rdgen-ahss ahss blog general main-blog metallurgy news steel-grades |

| Talk Like a Metallurgist | defining steel, metallurgy, steel definitions, steel grades, steel nomenclature | 1stGen AHSS, 2ndGen AHSS, 3rdGen AHSS, AHSS, Blog, Conventional HSS, Lower Strength Steels, Metallurgy, Steel Grades | defining-steel metallurgy steel-definitions steel-grades steel-nomenclature | 1stgen-ahss 2ndgen-ahss 3rdgen-ahss ahss blog conventional-h-s-s lower-strength-steels metallurgy steel-grades |

| Martensite | 1stGen steel, AHSS, ASTM A980M, cold stamping, MART, martensite, Martensite metallurgy, microstructural components, microstructure, MS, SAE J2745, VDA 239-100 | 1stGen AHSS, AHSS, Steel Grades | 1stgen-steel ahss astm-a980m cold-stamping mart martensite martensite-metallurgy microstructural-components microstructure ms sae-j2745 vda-239-100 | 1stgen-ahss ahss steel-grades metallurgy |

| Press Hardened Steels | 1stGen steel, 3rd Gen, AHSS, AlSi, AS coating, Bake Hardenability, Boron Steel, critical cooling rate, Direct Press Hardening, E. Billur, hot forming, hot press forming, hot stamped boron, Hot Stamping, Indirect Press Hardening, martensite, Medium-Mn, PHS, PHS Grades Over 1500 MPa, PHS Grades with Tensile Strength Approximately 1500 MPa, PQS Grades with High Elongation, Pre-cooled Direct Process, Press Hardening, Press Hardening Steels, Press Quenched Steel, quenching, Stainless, VDA 239-500, Zn coated PHS | 1stGen AHSS, AHSS, Press Hardened Steels, Steel Grades | 1stgen-steel 3rd-gen ahss alsi as-coating bake-hardenability boron-steel critical-cooling-rate direct-press-hardening e-billur hot-forming hot-press-forming hot-stamped-boron hot-stamping indirect-press-hardening martensite medium-mn phs phs-grades-over-1500-mpa phs-grades-with-tensile-strength-approximately-1500-mpa pqs-grades-with-high-elongation pre-cooled-direct-process press-hardening press-hardening-steels press-quenched-steel quenching stainless vda-239-500 zn-coated-phs | 1stgen-ahss ahss press-hardened-steels steel-grades metallurgy forming |

| Defining Steels | 3rd Gen, 3rd Generation, AHSS, banana diagram, bubble diagram, defining AHSS, defining UHSS, football diagram, Global Formability Diagram, Hance Diagram, Local Formability, local/global formability map, microstructural components, microstructure, nomenclature, syntax, tensile, terminology, UHSS, yield | Metallurgy | 3rd-gen 3rd-generation ahss banana-diagram bubble-diagram defining-ahss defining-uhss football-diagram global-formability-diagram hance-diagram local-formability local-global-formability-map microstructural-components microstructure nomenclature syntax tensile terminology uhss yield | metallurgy |

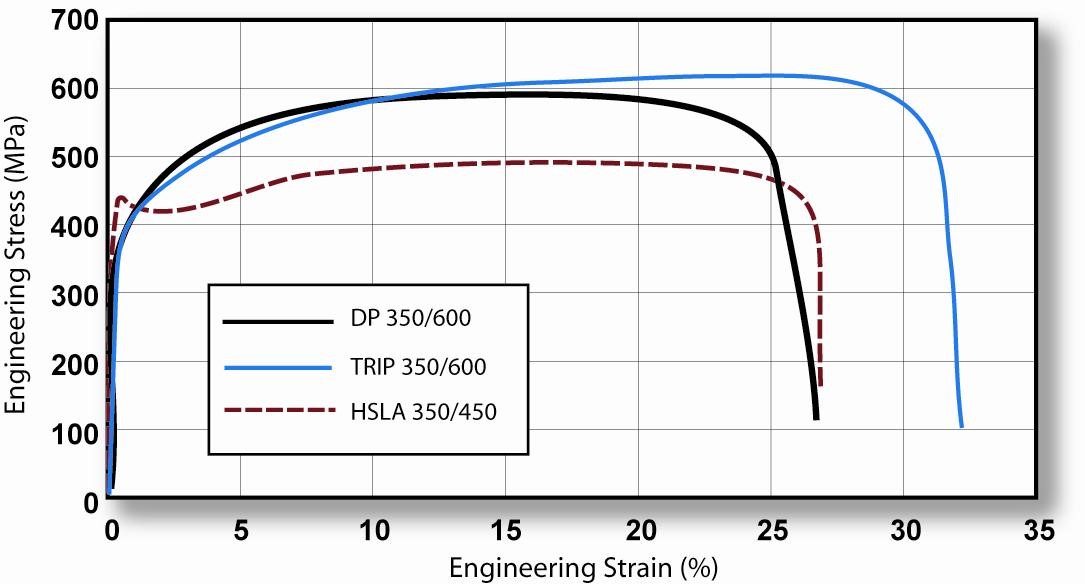

| Dual Phase | 1stGen steel, AHSS, ASTM A1088, bake hardening effect, DP, Dual Phase, EN 10338, ferrite, JFS A2001, JIS G3135, martensite, microstructure, SAE J2745, Strain Hardening Exponent, VDA 239-100, work hardening | 1stGen AHSS, AHSS, Steel Grades | 1stgen-steel ahss astm-a1088 bake-hardening-effect dp dual-phase en-10338 ferrite jfs-a2001 jis-g3135 martensite microstructure sae-j2745 strain-hardening-exponent vda-239-100 work-hardening | 1stgen-ahss ahss steel-grades metallurgy |

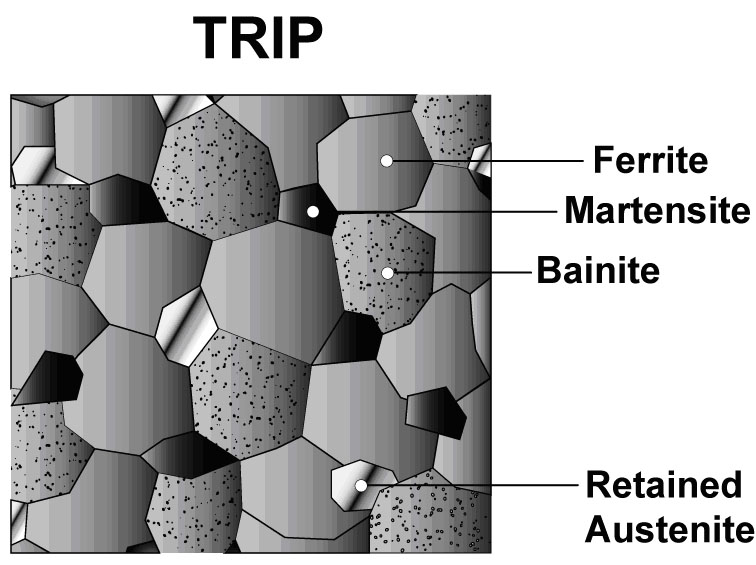

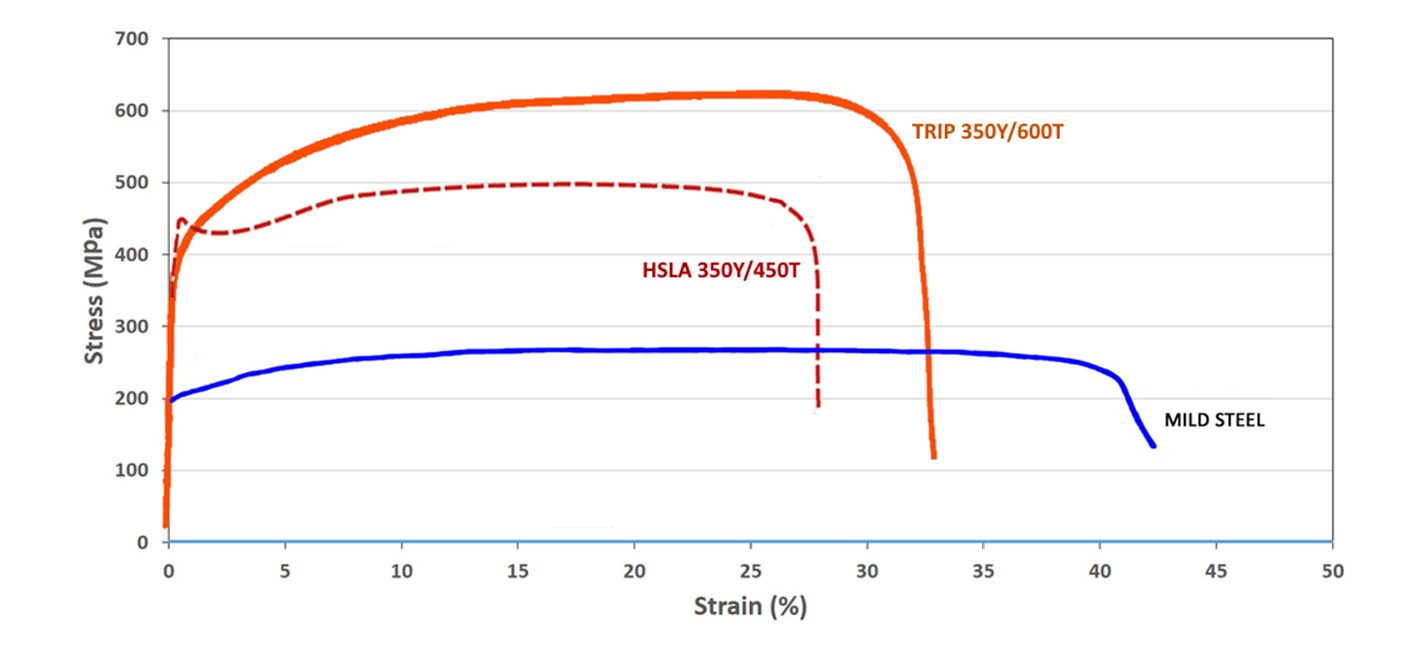

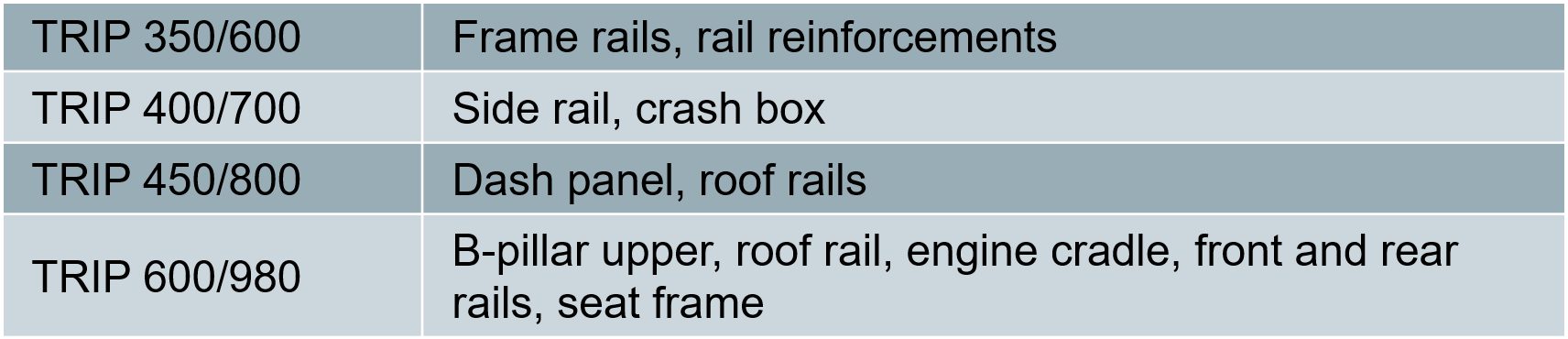

| Transformation Induced Plasticity (TRIP) | 1stGen steel, 3rd Generation, AHSS, ASTM A1088, Bainite, EN 10338, ferrite, JFS A2001, martensite, microstructure, retained austenite, SAE J2745, Strain Hardening Exponent, Transformation Induced Plasticity, TRIP, TRIP Effect, TRIP metallurgy, VDA 239-100, work hardening | 1stGen AHSS, 3rdGen AHSS, AHSS, Steel Grades | 1stgen-steel 3rd-generation ahss astm-a1088 bainite en-10338 ferrite jfs-a2001 martensite microstructure retained-austenite sae-j2745 strain-hardening-exponent transformation-induced-plasticity trip trip-effect trip-metallurgy vda-239-100 work-hardening | 1stgen-ahss 3rdgen-ahss ahss steel-grades metallurgy |

| Complex Phase | 1stGen steel, AHSS, ASTM A1088, Bainite, bendability, Bending, Complex Phase, CP, EN 10338, ferrite, Local Formability, martensite, microalloy, microstructural components, microstructure, precipitation strengthening, retained austenite, VDA 239-100 | 1stGen AHSS, AHSS, Steel Grades | 1stgen-steel ahss astm-a1088 bainite bendability bending complex-phase cp en-10338 ferrite local-formability martensite microalloy microstructural-components microstructure precipitation-strengthening retained-austenite vda-239-100 | 1stgen-ahss ahss steel-grades metallurgy |

| Ferrite-Bainite | 1stGen steel, AHSS, Bainite, cut edge stretching, edge stretchability, EN 10338, FB, ferrite, Ferrite-Bainite, HHE, hole expansion, Hole Extrusion, Hole Flanging, hot rolled steel, JFS A2001, microstructural components, microstructure, Stretchability, Stretching, VDA 239-100 | 1stGen AHSS, AHSS, Steel Grades | 1stgen-steel ahss bainite cut-edge-stretching edge-stretchability en-10338 fb ferrite ferrite-bainite hhe hole-expansion hole-extrusion hole-flanging hot-rolled-steel jfs-a2001 microstructural-components microstructure stretchability stretching vda-239-100 | 1stgen-ahss ahss steel-grades metallurgy |

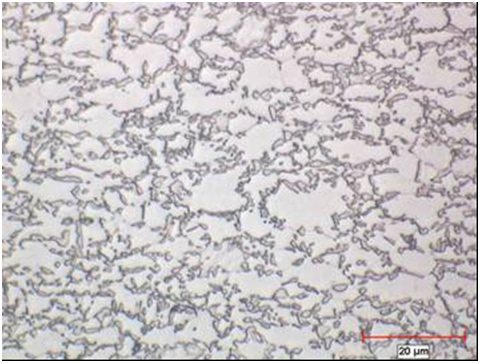

| Ultra-Low Carbon (DDS – EDDS) | DDS, deep drawing steel, EDDS, extra deep drawing steel, ferrite, ferrite Ultra-low carbon mild steel, microstructure, mild steel, ULC, ultra low carbon, vacuum degassed, VD-IF | Lower Strength Steels, Steel Grades | dds deep-drawing-steel edds extra-deep-drawing-steel ferrite ferrite-ultra-low-carbon-mild-steel microstructure mild-steel ulc ultra-low-carbon vacuum-degassed vd-if | lower-strength-steels steel-grades metallurgy |

| 3rd Generation Steels | 3rd Gen, Advanced High-Strength Steels, AHSS, Carbide Free Bainite, CFB, CH, complex phase high ductility, CP-HD, DH, downgauging, DP-HD, dual phase - high ductility, high ductility, Intercritical anneal, manganese, Medium-Mn, overaging, QP, Quench and Partition, TBF, Third Generation, TRIP Assisted Bainitic Ferrite, TRIP Effect | 3rdGen AHSS, AHSS, Steel Grades | 3rd-gen advanced-high-strength-steels ahss carbide-free-bainite cfb ch complex-phase-high-ductility cp-hd dh downgauging dp-hd dual-phase-high-ductility high-ductility intercritical-anneal manganese medium-mn overaging qp quench-and-partition tbf third-generation trip-assisted-bainitic-ferrite trip-effect | 3rdgen-ahss ahss steel-grades metallurgy |

| Carbon-Manganese (CMn) | ASTM A1008M, C-Mn, carbon, carbon and manganese, Carbon-manganese, CMn, conventional high-strength steel, high strength steel, JFS A2001, JIS G3135, manganese, structural steel, Yield Strength | Conventional HSS, Steel Grades | astm-a1008m c-mn carbon carbon-and-manganese carbon-manganese cmn conventional-high-strength-steel high-strength-steel jfs-a2001 jis-g3135 manganese structural-steel yield-strength | conventional-h-s-s steel-grades metallurgy |

| High Strength Low Alloy Steel | ASTM, ASTM A1008M, C-Mn, Carbon-manganese, CMn, conventional high-strength steel, EN 10268, High strength low alloy, HSLA, JFS A2001, JIS G3135, LA, microalloy, precipitation strengthening, VDA 239-100, Yield Strength | Conventional HSS, Steel Grades | astm astm-a1008m c-mn carbon-manganese cmn conventional-high-strength-steel en-10268 high-strength-low-alloy hsla jfs-a2001 jis-g3135 la microalloy precipitation-strengthening vda-239-100 yield-strength | conventional-h-s-s steel-grades metallurgy |

| Mild Steels | ASTM A1008M, DQ, DQAK, DQSK, draw quality steel, drawing steel, DS, EN 10130, ferrite, JFS A2001, JIS G3141, low carbon, microstructure, mild steel, ULC, ultra low carbon, VDA 239-100 | Lower Strength Steels, Steel Grades | astm-a1008m dq dqak dqsk draw-quality-steel drawing-steel ds en-10130 ferrite jfs-a2001 jis-g3141 low-carbon microstructure mild-steel ulc ultra-low-carbon vda-239-100 | lower-strength-steels steel-grades metallurgy |

| Interstitial-Free High Strength | EDDS, EN 10268, IF, IF-HS, IF-Rephos, Interstitial-Free High Strength, JFS A2001, Rephosphorized, ULC, VD-IF, VDA 239-100 | Conventional HSS, Steel Grades | edds en-10268 if if-hs if-rephos interstitial-free-high-strength jfs-a2001 rephosphorized ulc vd-if vda-239-100 | conventional-h-s-s steel-grades metallurgy |

| Bake Hardenable | ASTM A1008M, Bake Hardenability, Bake hardenable, bake hardening, bake hardening effect, Baking Index, BH, BH effect, BHI, carbon, dent, dislocations, EN10268, JFS A2001, JIS G3135, microstructural components, paint bake, SAE J2575, strain aging, VDA239-100, work hardening | AHSS, Conventional HSS, Steel Grades | astm-a1008m bake-hardenability bake-hardenable bake-hardening bake-hardening-effect baking-index bh bh-effect bhi carbon dent dislocations en10268 jfs-a2001 jis-g3135 microstructural-components paint-bake sae-j2575 strain-aging vda239-100 work-hardening | ahss conventional-h-s-s steel-grades metallurgy |

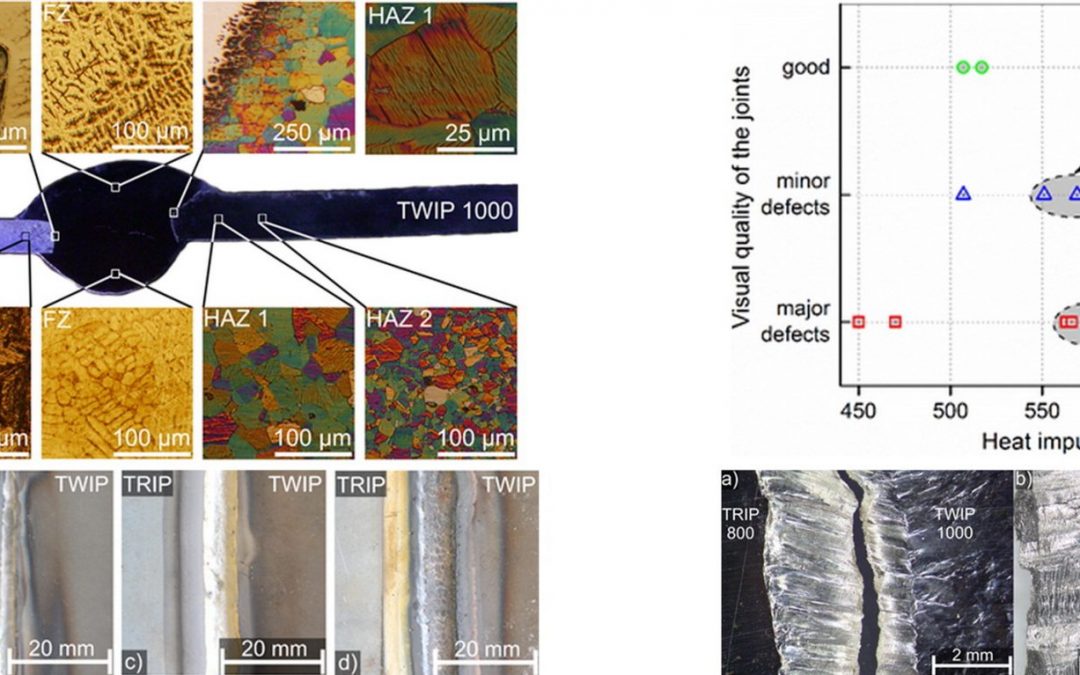

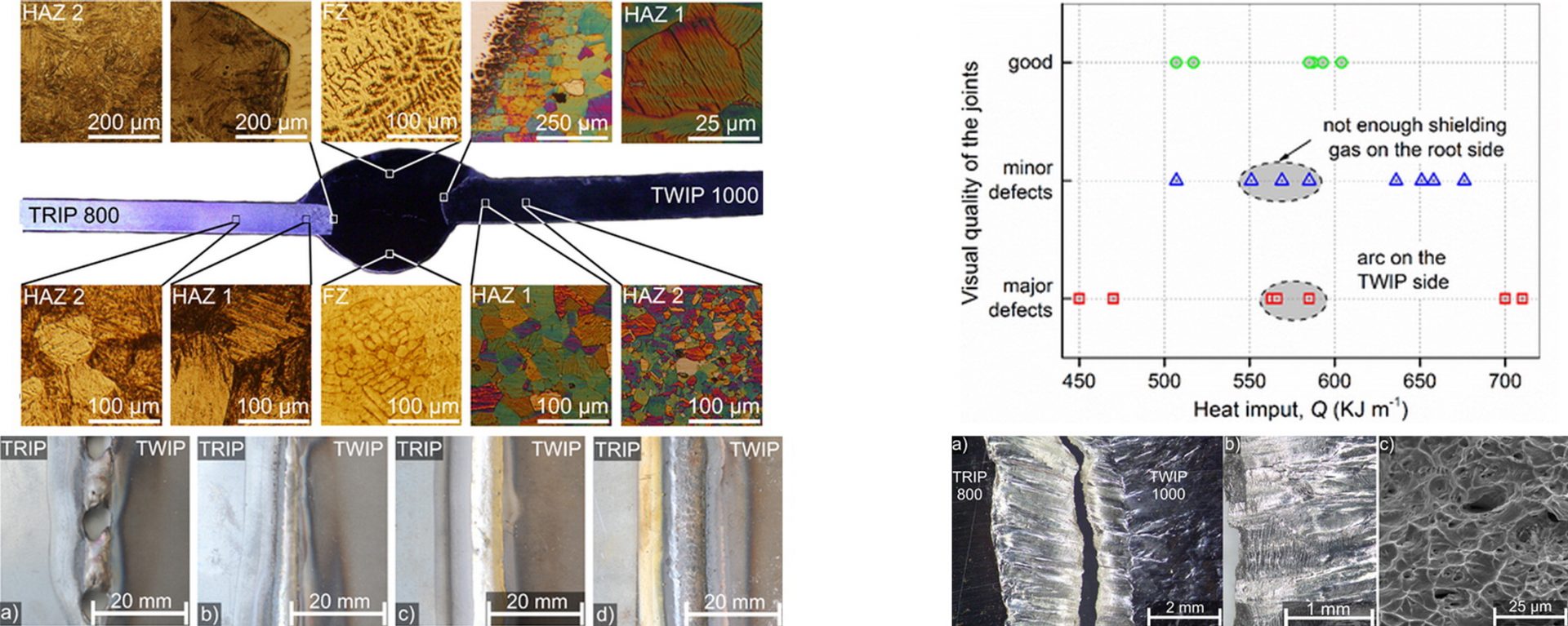

| Twinning Induced Plasticity | 2nd Gen, AHSS, dynamic strain aging, Fe-Mn, manganese, microstructure, PLC effect, Portevin-LeChatelier effect, Strain rate sensitivity, stretch formability, Twinning Induced Plasticity, TWIP, TWIP4EU | 2ndGen AHSS, AHSS, Steel Grades | 2nd-gen ahss dynamic-strain-aging fe-mn manganese microstructure plc-effect portevin-lechatelier-effect strain-rate-sensitivity stretch-formability twinning-induced-plasticity twip twip4eu | 2ndgen-ahss ahss steel-grades metallurgy |