1stGen AHSS, AHSS, Steel Grades

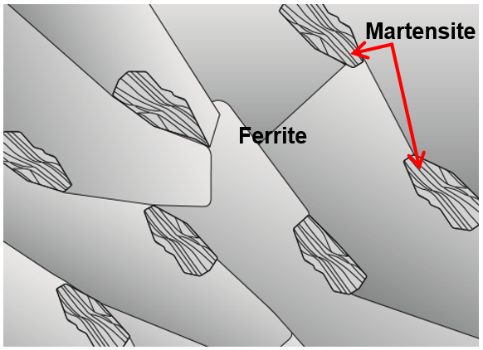

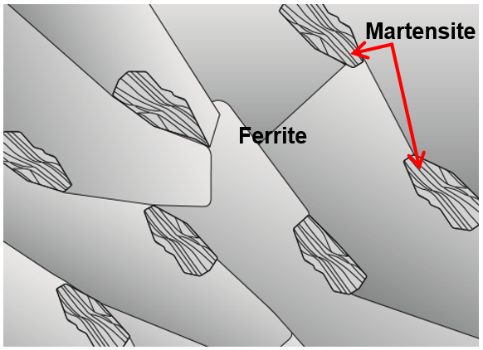

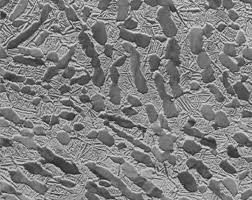

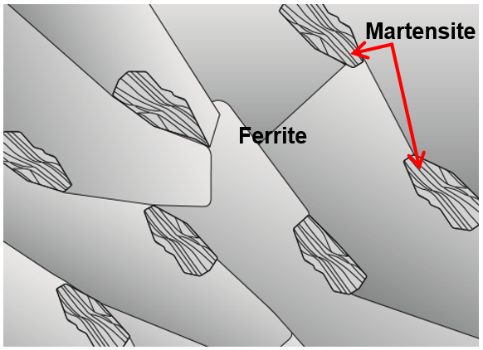

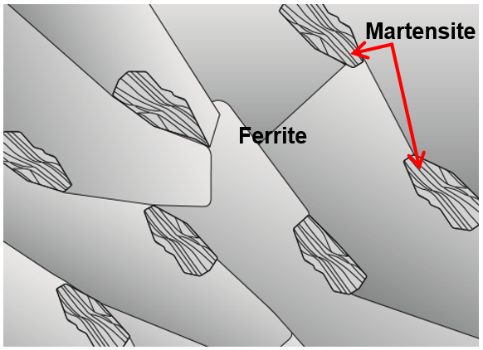

Dual Phase (DP) steels have a microstructure consisting of a ferritic matrix with martensitic islands as a hard second phase, shown schematically in Figure 1. The soft ferrite phase is generally continuous, giving these steels excellent ductility. When these steels deform, strain is concentrated in the lower-strength ferrite phase surrounding the islands of martensite, creating the unique high initial work-hardening rate (n-value) exhibited by these steels. Figure 2 is a micrograph showing the ferrite and martensite constituents.

Figure 1: Schematic of a Dual Phase steel microstructure showing islands of martensite in a matrix of ferrite.

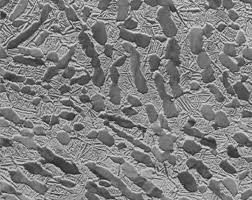

Figure 2: Micrograph of Dual Phase Steel

Hot rolled DP steels do not have the benefit of an annealing cycle, so the dual phase microstructure must be achieved by controlled cooling from the austenite phase after exiting the hot strip mill finishing stands and before coiling. This typically requires a more highly alloyed chemistry than cold rolled DP steels require. Higher alloying is generally associated with a change in welding practices.

Continuously annealed cold-rolled and hot-dip coated Dual Phase steels are produced by controlled cooling from the two-phase ferrite plus austenite (α + γ) region to transform some austenite to ferrite before a rapid cooling transforms the remaining austenite to martensite. Due to the production process, small amounts of other phases (bainite and retained austenite) may be present.

Higher strength dual phase steels are typically achieved by increasing the martensite volume fraction. Depending on the composition and process route, steels requiring enhanced capability to resist cracking on a stretched edge (as typically measured by hole expansion capacity) can have a microstructure containing significant quantities of bainite.

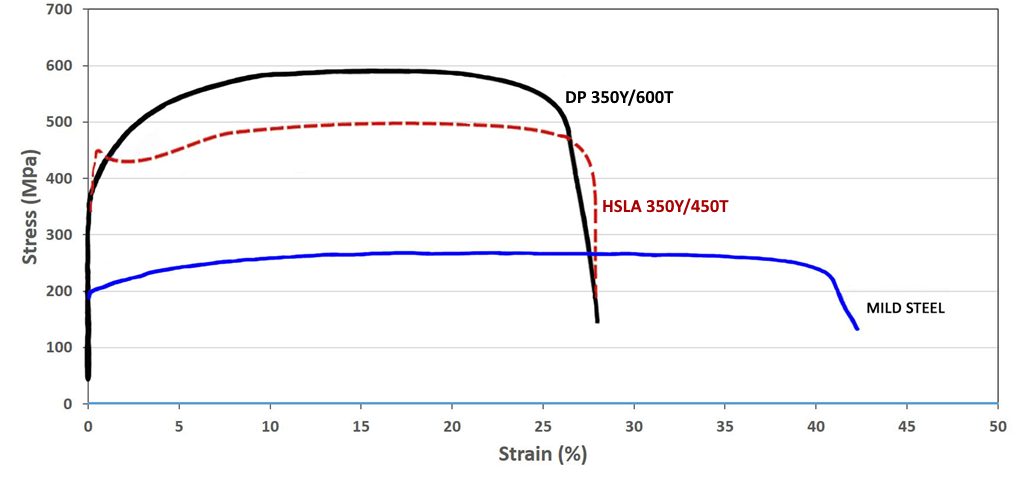

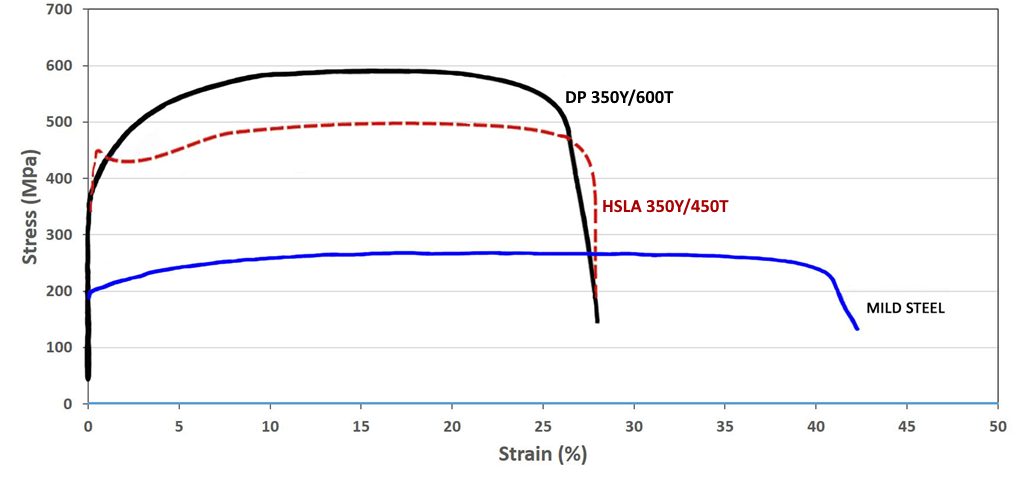

The work hardening rate plus excellent elongation creates DP steels with much higher ultimate tensile strengths than conventional steels of similar yield strength. Figure 3 compares the engineering stress-strain curve for HSLA steel to a DP steel curve of similar yield strength. The DP steel exhibits higher initial work hardening rate, higher ultimate tensile strength, and lower YS/TS ratio than the HSLA with comparable yield strength. Additional engineering and true stress-strain curves for DP steel grades are presented in Figures 4 and 5.

Figure 3: A comparison of stress strain curves for mild steel, HSLA 350/450, and DP 350/600K-1

Figure 4: Engineering stress-strain curves for a series of DP steel grades.S-5, V-1 Sheet thicknesses: DP 250/450 and DP 500/800 = 1.0mm. All other steels were 1.8-2.0mm.

Figure 5: True stress-strain curves for a series of DP steel grades.S-5, V-1 Sheet thicknesses: DP 250/450 and DP 500/800 = 1.0mm. All other steels were 1.8-2.0mm.

DP and other AHSS also have a bake hardening effect that is an important benefit compared to conventional higher strength steels. The extent of the bake hardening effect in AHSS depends on an adequate amount of forming strain for the specific chemistry and thermal history of the steel.

In DP steels, carbon enables the formation of martensite at practical cooling rates by increasing the hardenability of the steel. Manganese, chromium, molybdenum, vanadium, and nickel, added individually or in combination, also help increase hardenability. Carbon also strengthens the martensite as a ferrite solute strengthener, as do silicon and phosphorus. These additions are carefully balanced, not only to produce unique mechanical properties, but also to maintain the generally good resistance spot welding capability. However, when welding the higher strength grades (DP 700/1000 and above) to themselves, the spot weldability may require adjustments to the welding practice.

Examples of current production grades of DP steels and typical automotive applications include:

| DP 300/500 |

Roof outer, door outer, body side outer, package tray, floor panel |

| DP 350/600 |

Floor panel, hood outer, body side outer, cowl, fender, floor reinforcements |

| DP 500/800 |

Body side inner, quarter panel inner, rear rails, rear shock reinforcements |

| DP 600/980 |

Safety cage components (B-pillar, floor panel tunnel, engine cradle, front sub-frame package tray, shotgun, seat) |

| DP 700/1000 |

Roof rails |

| DP 800/1180 |

B-Pillar upper |

Some of the specifications describing uncoated cold rolled 1st Generation dual phase (DP) steel are included below, with the grades typically listed in order of increasing minimum tensile strength and ductility. Different specifications may exist which describe hot or cold rolled, uncoated or coated, or steels of different strengths. Many automakers have proprietary specifications which encompass their requirements.

- ASTM A1088, with the terms Dual phase (DP) steel Grades 440T/250Y, 490T/290Y, 590T/340Y, 780T/420Y, and 980T/550YA-22

- EN 10338, with the terms HCT450X, HCT490X, HCT590X, HCT780X, HCT980X, HCT980XG, and HCT1180XD-6

- JIS G3135, with the terms SPFC490Y, SPFC540Y, SPFC590Y, SPFC780Y and SPFC980YJ-3

- JFS A2001, with the terms JSC590Y, JSC780Y, JSC980Y, JSC980YL, JSC980YH, JSC1180Y, JSC1180YL, and JSC1180YHJ-23

- VDA 239-100, with the terms CR290Y490T-DP, CR330Y590T-DP, CR440Y780T-DP, CR590Y980T-DP, and CR700Y980T-DPV-3

- SAE J2745, with terms Dual Phase (DP) 440T/250Y, 490T/290Y, 590T/340Y, 6907/550Y, 780T/420Y, and 980T/550YS-18

1stGen AHSS, 3rdGen AHSS, AHSS, Steel Grades

topofpage

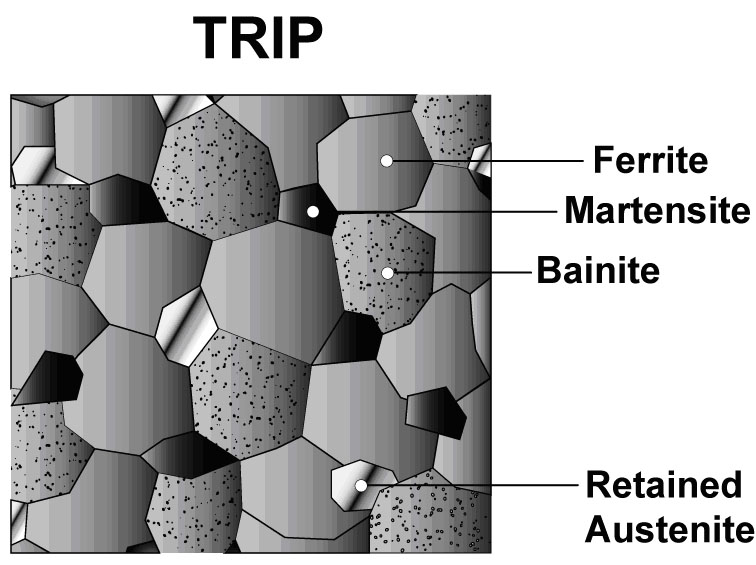

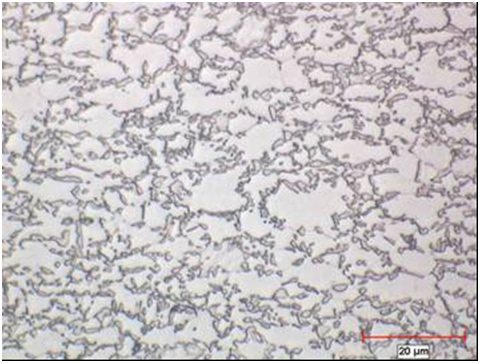

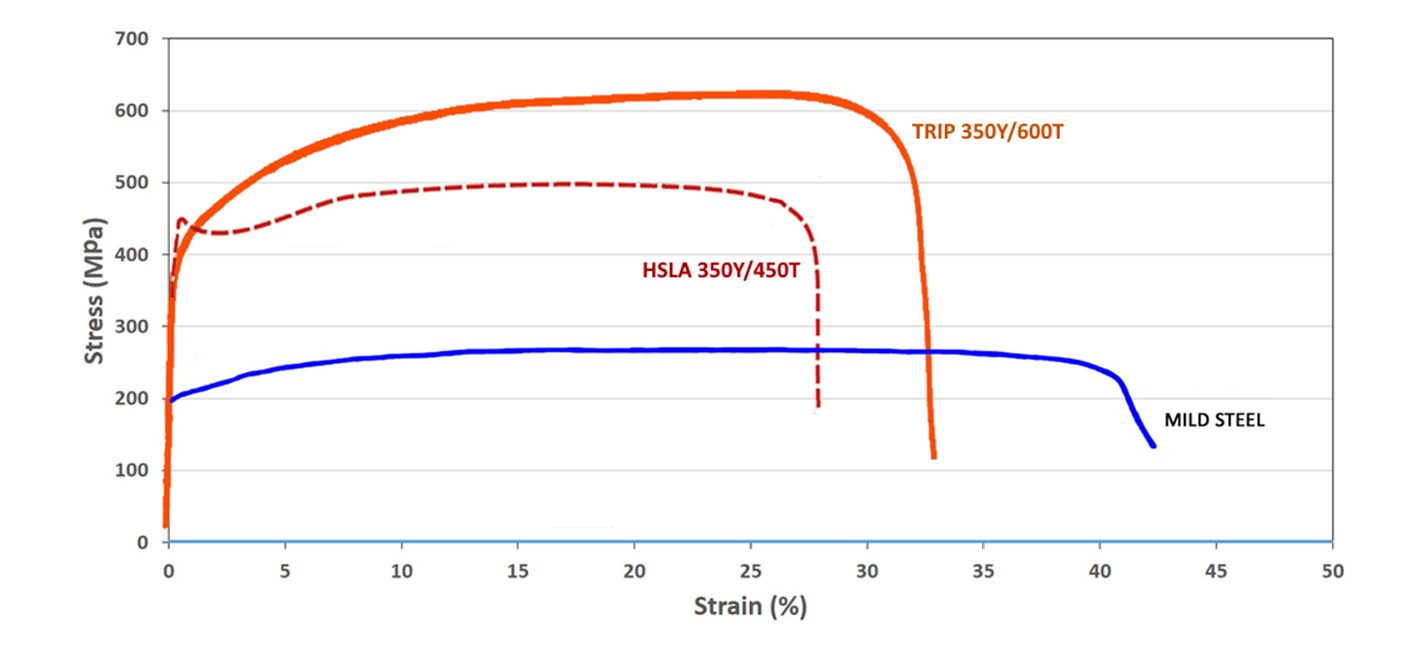

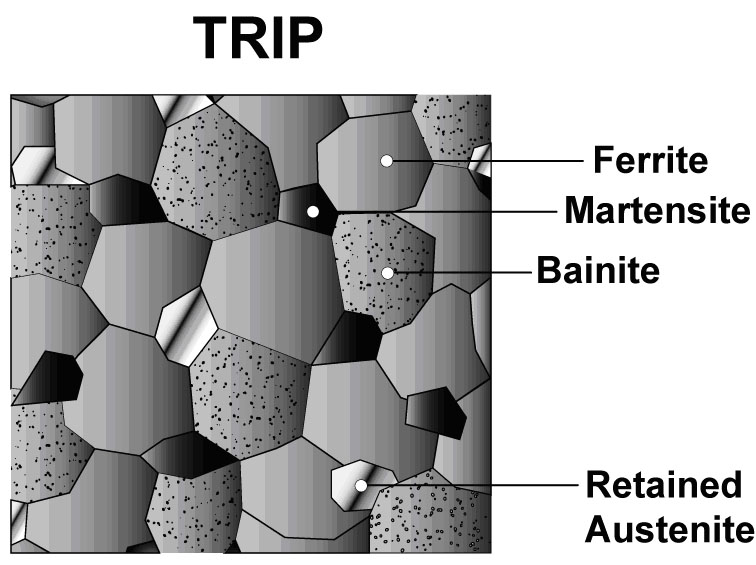

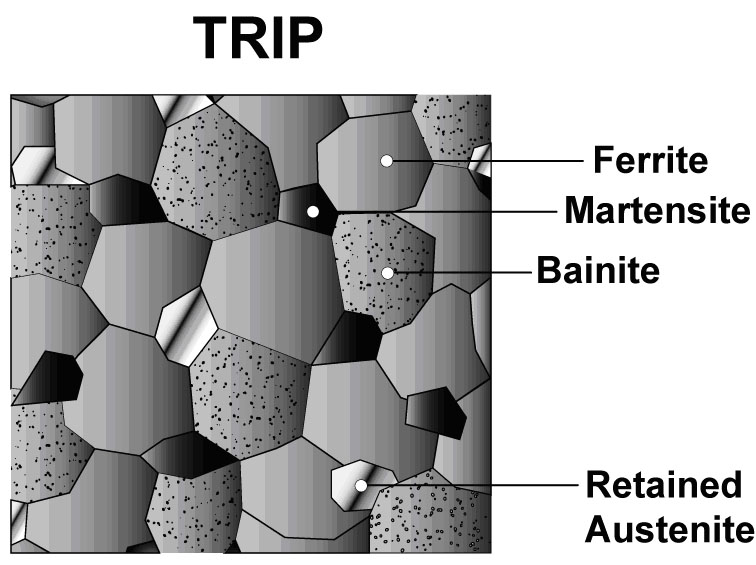

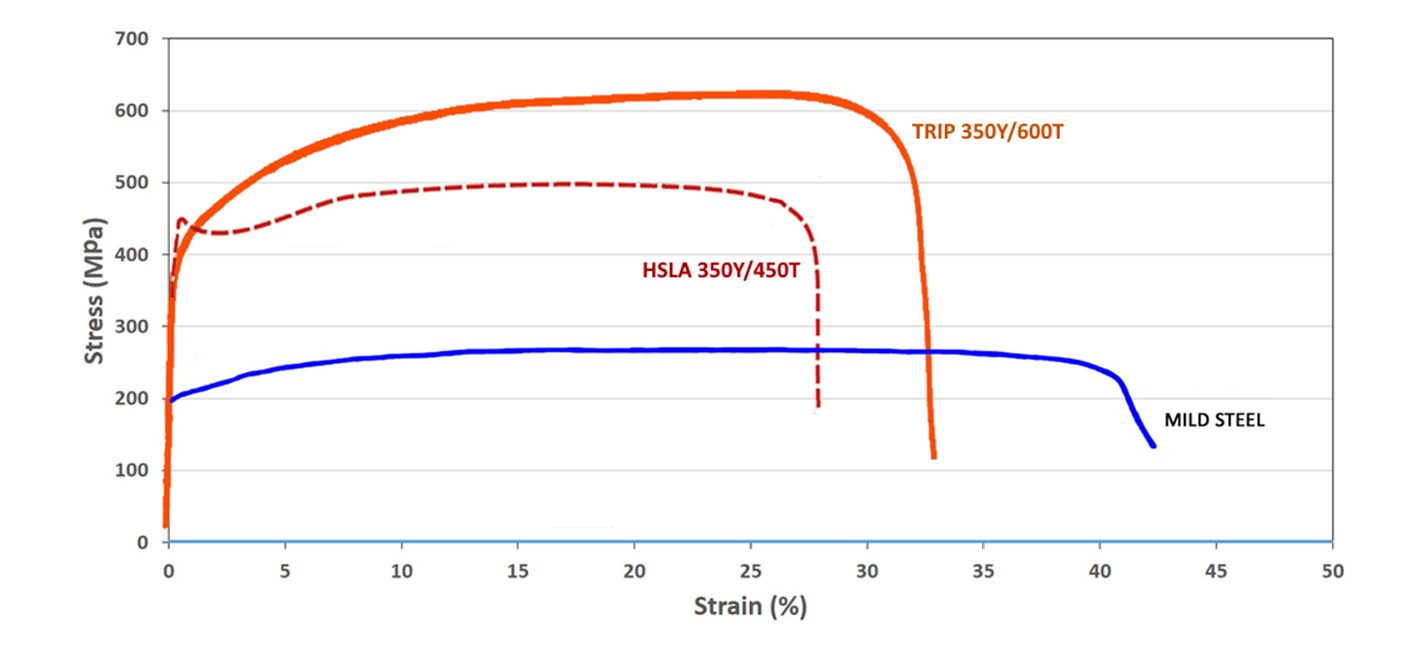

The microstructure of Transformation Induced Plasticity (TRIP) steels contains a matrix of ferrite, with retained austenite, martensite, and bainite present in varying amounts. Production of TRIP steels typically requires the use of an isothermal hold at an intermediate temperature, which produces some bainite. Higher silicon and carbon content of TRIP steels result in significant volume fractions of retained austenite in the final microstructure. Figure 1 shows a schematic of TRIP steel microstructure, with Figure 2 showing a micrograph of an actual sample of TRIP steel. Figure 3 compares the engineering stress-strain curve for HSLA steel to a TRIP steel curve of similar yield strength.

Figure 1: Schematic of a TRIP steel microstructure showing a matrix of ferrite, with martensite, bainite and retained austenite as the additional phases.

Figure 2: Micrograph of Transformation Induced Plasticity steel.

Figure 3: A comparison of stress strain curves for mild steel, HSLA 350/450, and TRIP 350/600.K-1

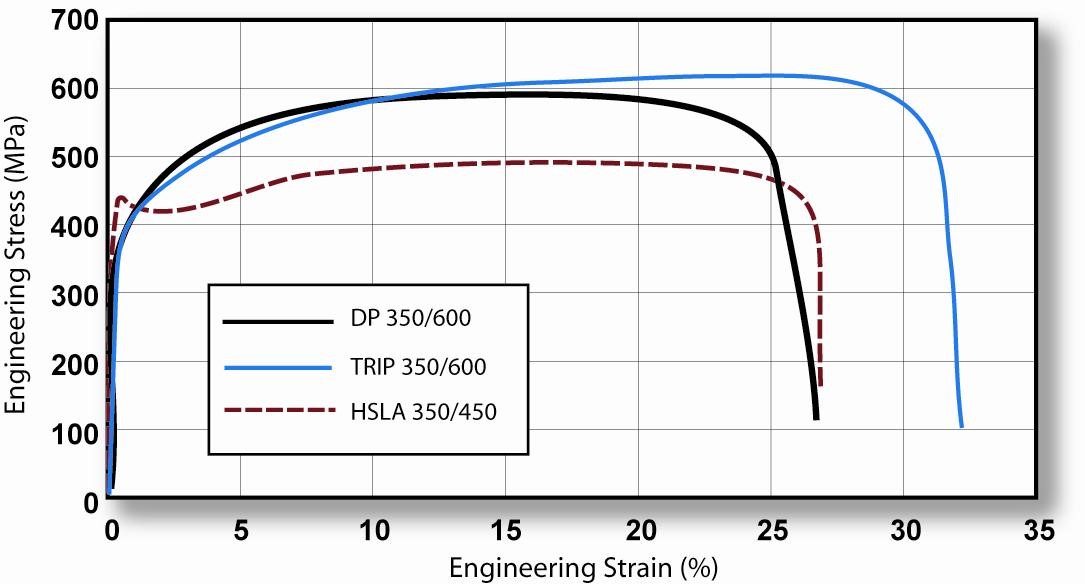

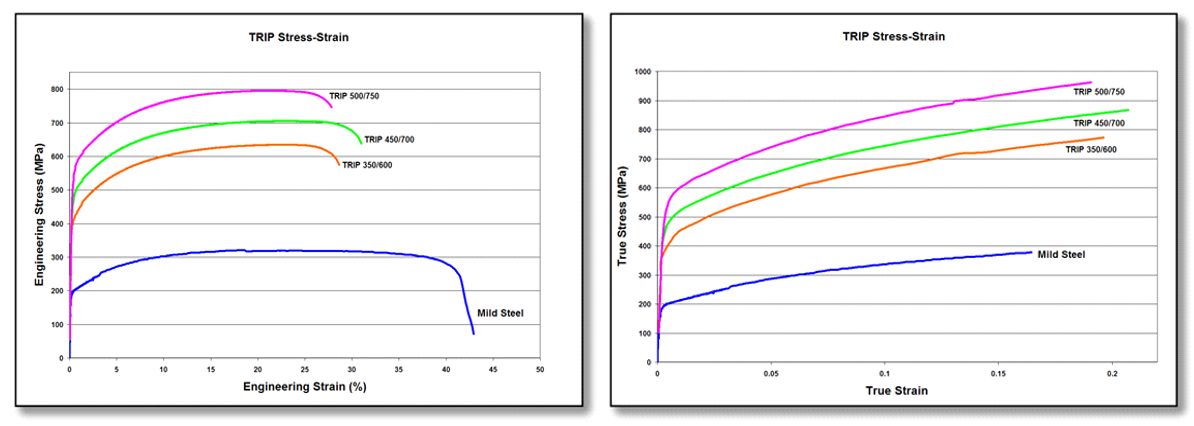

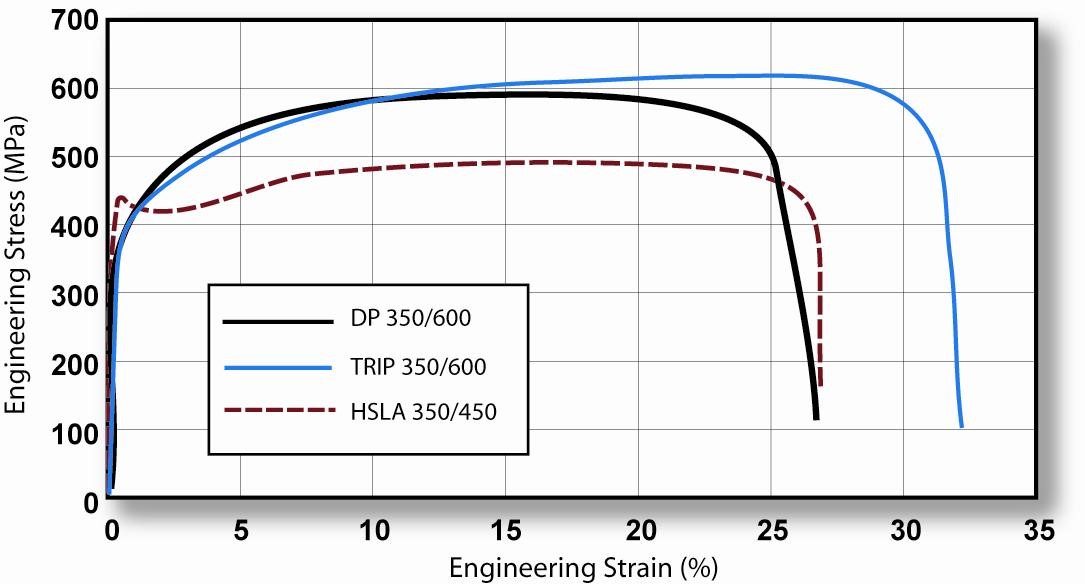

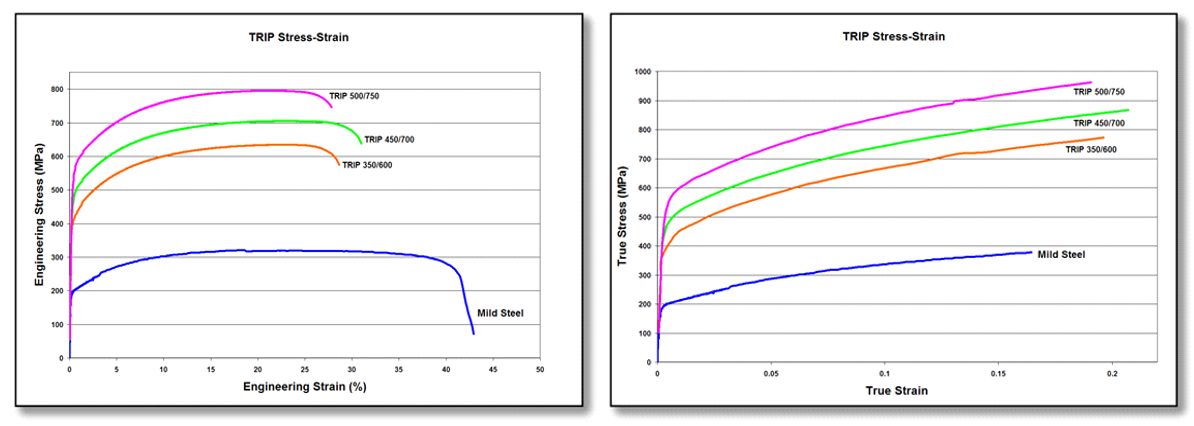

During deformation, the dispersion of hard second phases in soft ferrite creates a high work hardening rate, as observed in the DP steels. However, in TRIP steels the retained austenite also progressively transforms to martensite with increasing strain, thereby increasing the work hardening rate at higher strain levels. This is known as the TRIP Effect. This is illustrated in Figure 4, which compares the engineering stress-strain behavior of HSLA, DP and TRIP steels of nominally the same yield strength. The TRIP steel has a lower initial work hardening rate than the DP steel, but the hardening rate persists at higher strains where work hardening of the DP begins to diminish. Additional engineering and true stress-strain curves for TRIP steel grades are shown in Figure 5.

Figure 4: TRIP 350/600 with a greater total elongation than DP 350/600 and HSLA 350/450. K-1

Figure 5: Engineering stress-strain (left graphic) and true stress-strain (right graphic) curves for a series of TRIP steel grades. Sheet thickness: TRIP 350/600 = 1.2mm, TRIP 450/700 = 1.5mm, TRIP 500/750 = 2.0mm, and Mild Steel = approx. 1.9mm. V-1

The strain hardening response of TRIP steels are substantially higher than for conventional HSS, resulting in significantly improved formability in stretch deformation. This response is indicated by a comparison of the n-value for the grades. The improvement in stretch formability is particularly useful when designers take advantage of the improved strain hardening response to design a part utilizing the as-formed mechanical properties. High n-value persists to higher strains in TRIP steels, providing a slight advantage over DP in the most severe stretch forming applications.

Austenite is a higher temperature phase and is not stable at room temperature under equilibrium conditions. Along with a specific thermal cycle, carbon content greater than that used in DP steels are needed in TRIP steels to promote room-temperature stabilization of austenite. Retained austenite is the term given to the austenitic phase that is stable at room temperature.

Higher contents of silicon and/or aluminum accelerate the ferrite/bainite formation. These elements assist in maintaining the necessary carbon content within the retained austenite. Suppressing the carbide precipitation during bainitic transformation appears to be crucial for TRIP steels. Silicon and aluminum are used to avoid carbide precipitation in the bainite region.

The carbon level of the TRIP alloy alters the strain level at which the TRIP Effect occurs. The strain level at which retained austenite begins to transform to martensite is controlled by adjusting the carbon content. At lower carbon levels, retained austenite begins to transform almost immediately upon deformation, increasing the work hardening rate and formability during the stamping process. At higher carbon contents, retained austenite is more stable and begins to transform only at strain levels beyond those produced during forming. At these carbon levels, retained austenite transforms to martensite during subsequent deformation, such as a crash event.

TRIP steels therefore can be engineered to provide excellent formability for manufacturing complex AHSS parts or to exhibit high strain hardening during crash deformation resulting in excellent crash energy absorption.

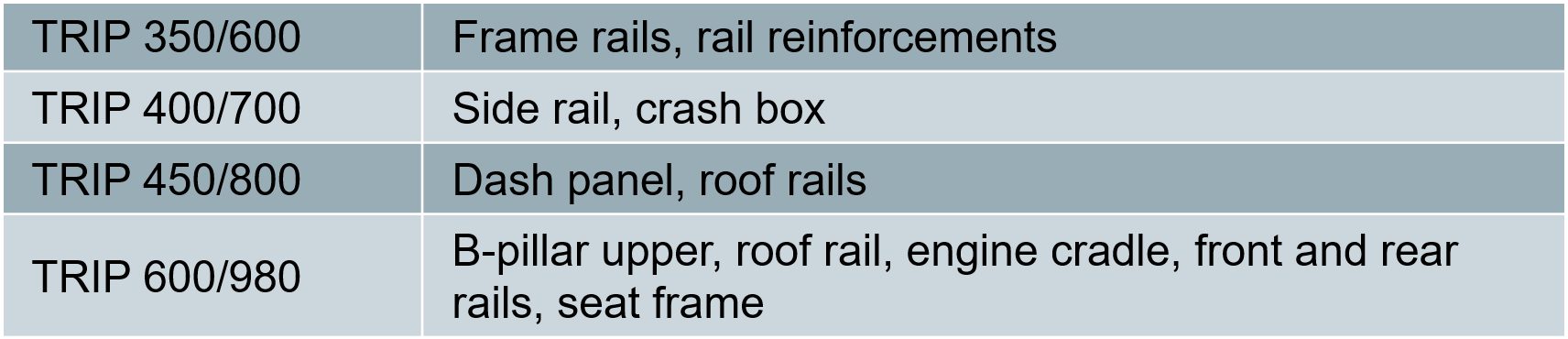

The additional alloying requirements of TRIP steels degrade their resistance spot-welding behavior. This can be addressed through weld cycle modification, such as the use of pulsating welding or dilution welding. Table 1 provides a list of current production grades of TRIP steels and example automotive applications:

Table 1: Current Production Grades Of TRIP Steels And Example Automotive Applications.

Some of the specifications describing uncoated cold rolled 1st Generation transformation induced plasticity (TRIP) steel are included below, with the grades typically listed in order of increasing minimum tensile strength and ductility. Different specifications may exist which describe hot or cold rolled, uncoated or coated, or steels of different strengths. Many automakers have proprietary specifications which encompass their requirements.

• ASTM A1088, with the terms Transformation induced plasticity (TRIP) steel Grades 690T/410Y and 780T/440YA-22

• JFS A2001, with the terms JSC590T and JSC780TJ-23

• EN 10338, with the terms HCT690T and HCT780TD-18

• VDA 239-100, with the terms CR400Y690T-TR and CR450Y780T-TRV-3

• SAE J2745, with terms Transformation Induced Plasticity (TRIP) 590T/380Y, 690T/400Y, and 780T/420YS-18

Transformation Induced Plasticity Effect

Austenite is not stable at room temperature under equilibrium conditions. An austenitic microstructure is retained at room temperature with the combined use of a specific chemistry and controlled thermal cycle. Deformation from sheet forming provides the necessary energy to allow the crystallographic structure to change from austenite to martensite. There is insufficient time and temperature for substantial diffusion of carbon to occur from carbon-rich austenite, which results in a high-carbon (high strength) martensite after transformation. Transformation to high strength martensite continues as deformation increases, as long as retained austenite is still available to be transformed.

Alloys capable of the TRIP effect are characterized by a high ductility – high strength combination. Such alloys include 1st Gen AHSS TRIP steels, as well as several 3rd Gen AHSS grades like TRIP-Assisted Bainitic Ferrite, Carbide Free Bainite, and Quench & Partition Steels.

Back to the Top

![Ferrite-Bainite]()

1stGen AHSS, AHSS, Steel Grades

Ferrite-Bainite (FB) steels are hot rolled steels typically found in applications requiring improved edge stretch capability, balancing strength and formability. The microstructure of FB steels contains the phases ferrite and bainite. High elongation is associated with ferrite, and bainite is associated with good edge stretchability. A fine grain size with a minimized hardness differences between the phases further enhance hole expansion performance. These microstructural characteristics also leads to improved fatigue strength relative to the tensile strength.

FB steels have a fine microstructure of ferrite and bainite. Strengthening comes from by both grain refinement and second phase hardening with bainite. Relatively low hardness differences within a fine microstructure promotes good Stretch Flangable (SF) and high hole expansion (HHE) performance, both measures of local formability. Figure 1 shows a schematic Ferrite-Bainite steel microstructure, with a micrograph of FB 400Y540T shown in Figure 2.

Figure 1: Schematic Ferrite-Bainite steel microstructure.

Figure 2: Micrograph of Ferrite-Bainite steel, HR400Y540T-FB.H-21

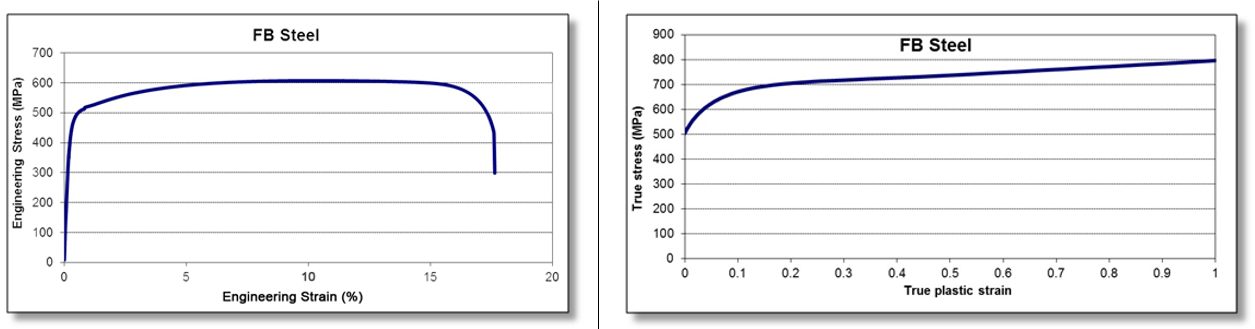

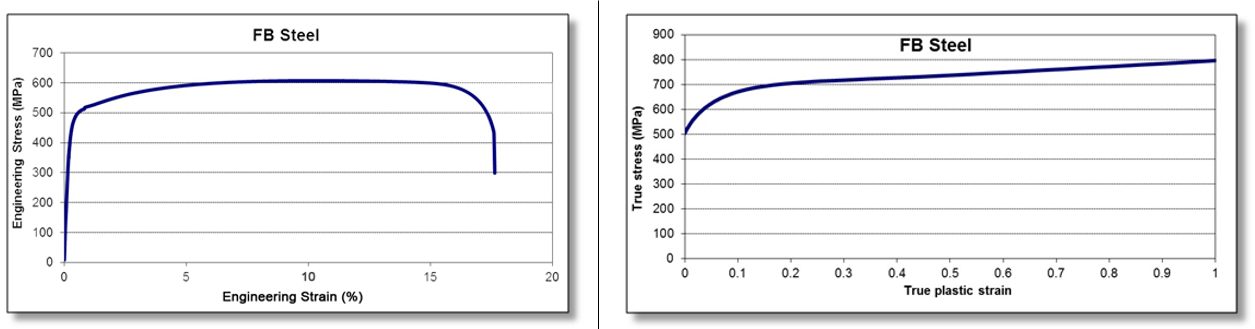

The primary advantage of FB steels over HSLA and DP steels is the improved stretchability of sheared edges as measured by the hole expansion test. Compared to HSLA steels with the same level of strength, FB steels also have a higher strain hardening exponent (n-value) and increased total elongation. Figure 3 compares FB 450/600 with HSLA 350/450 steel. Engineering and true stress-strain curves for FB steel grades are shown in Figure 4.

Figure 3: A comparison of stress strain curves for mild steel, HSLA 350/450, and FB 450/600.

Figure 4: Engineering stress-strain (left graphic) and true stress-strain (right graphic) curve for FB 450/600.T-10

Examples of typical automotive applications benefitting from these high strength highly formable grades include automotive chassis and suspension parts such as upper and lower control arms, longitudinal beams, seat cross members, rear twist beams, engine sub-frames and wheels.

Some of the specifications describing uncoated hot rolled 1st Generation ferrite-bainite (FB) steel are included below, with the grades typically listed in order of increasing minimum tensile strength and ductility. Different specifications may exist which describe uncoated or coated versions of these grades. Many automakers have proprietary specifications which encompass their requirements.

- EN 10338, with the terms HDT450F and HDT580F D-18

- VDA239-100, with the terms HR300Y450T-FB, HR440Y580T-FB, and HR600Y780T-FB V-3

- JFS A2001, with the terms JSC440A and JSC590AJ-23

Conventional HSS, Steel Grades

Carbon-Manganese High Strength Steel

Carbon and manganese are the two most cost-effective alloying additions to increase strength. While effective at strengthening, these additions reduce ductility and toughness, and make welding more challenging.

The practical usage of these grades typically limits the highest strength to no more than 280 MPa. Adding enough carbon and manganese to achieve higher strength results in a product without sufficient ductility for challenging applications, low toughness, and welding difficulty. These products sometimes are referred to as structural steels, and achieve their strength from the mechanism of solid solution strengthening.

Until the commercialization of High Strength Low Alloy steels, the CMn approach was the only option for users to obtain a high strength sheet metal.

Some of the specifications describing uncoated cold rolled Carbon-Manganese (CMn) or structural steels are included below, with the grades typically listed in order of increasing minimum yield strength and ductility. Different specifications may exist which describe hot or cold rolled, uncoated or coated, or steels of different strengths. Many automakers have proprietary specifications which encompass their requirements. Note that ASTM terminology is based on minimum yield strength, while JIS and JFS standards are based on minimum tensile strength. Also note that JIS G3135 does not explicitly state that these grades must be supplied with a C-Mn chemistry. An HSLA approach is satisfactory as long as the mechanical property criteria are satisfied.

- ASTM A1008M, with the terms Grade 25 [170], Grade 30 [205], Grade 33 [230] Type 1, Grade 33 [230] Type 2, Grade 40 [275] Type 1, Grade 40 [275] Type 2, Grade 45 [310], Grade 50 [340], Grade 60 [410], Grade 70 [480], and Grade 80 [550] A-25

- JIS G3135 with the terms SPFC340, SPFC370, SPFC390, SPFC440, SPFC490, SPFC540, and SPFC590 J-3

- JFS A2001, with the terms JSC340W, JSC370W, JSC390W, and JSC440W J-23

Conventional HSS, Steel Grades

Carbon-Manganese Steels (CMn) are a lower cost approach to reach up to approximately 280MPa yield strength, but are limited in ductility, toughness and welding.

Increasing carbon and manganese, along with alloying with other elements like chromium and silicon, will increase strength, but have the same challenges as CMn steels with higher cost. An example is AISI/SAE 4130, a chromium-molybdenum (chromoly) medium carbon alloy steel. A wide range of properties are available, depending on the heat treatment of formed components. Welding conditions must be carefully controlled.

The 1980s saw the commercialization of high-strength low-alloy (HSLA) steels. In contrast with alloy steels, HSLA steels achieved higher strength with a much lower alloy content. Lower carbon content and lower alloying content leads to increased ductility, toughness, and weldability compared with grades achieving their strength from only solid solution strengthening like CMn steels or from alloying like AISI/SAE 4130. Lower alloying and elimination of post-forming heat treatment makes HSLA steels an economical approach for many applications.

This steelmaking approach allows for the production of sheet steels with yield strength levels now approaching 800 MPa. HSLA steels increase strength primarily by micro-alloying elements contributing to fine carbide precipitation, substitutional and interstitial strengthening, and grain-size refinement. HSLA steels are found in many body-in-white and underbody structural applications where strength is needed for increased in-service loads.

These steels may be referred to as microalloyed steels, since the carbide precipitation and grain-size refinement is achieved with only 0.05% to 0.10% of titanium, vanadium, and niobium, added alone or in combination with each other.

HSLA steels have a microstructure that is mostly precipitation-strengthened ferrite, with the amount of other constituents like pearlite and bainite being a function of the targeted strength level. More information about microstructural components is available here.

Some of the specifications describing uncoated cold rolled high strength low alloy (HSLA) steel are included below, with the grades typically listed in order of increasing minimum yield strength and ductility. Different specifications may exist which describe hot or cold rolled, uncoated or coated, or steels of different strengths. Many automakers have proprietary specifications which encompass their requirements. Note that ASTM, EN and VDA terminology is based on minimum yield strength, while JIS and JFS standards are based on minimum tensile strength. Also note that JIS G3135 does not explicitly state that these grades must be supplied with an HSLA chemistry. A C-Mn approach is satisfactory as long as the mechanical property criteria are satisfied.

- ASTM A1008M, with the terms HSLAS 45[310], 50[340], 55[380], 60[410], 65[450], and 70[480] along with HSLAS-F 50 [340], 60 [410], Grade 70 [480] and 80 [550]A-25

- EN10268, with the terms HC260LA, HC300LA, HC340LA, HC380LA, HC420LA, HC460LA, and HC500LAD-5

- JIS G3135, with the terms SPFC340, SPFC370, SPFC390, SPFC440, SPFC490, SPFC540, and SPFC590J-3

- JFS A2001, with the terms JSC440R and JSC590RJ-23

- VDA239-100, with the terms CR210LA, CR240LA, CR270LA, CR300LA, CR340LA, CR380LA, CR420LA, and CR460LAV-3