Blog, homepage-featured-top, main-blog

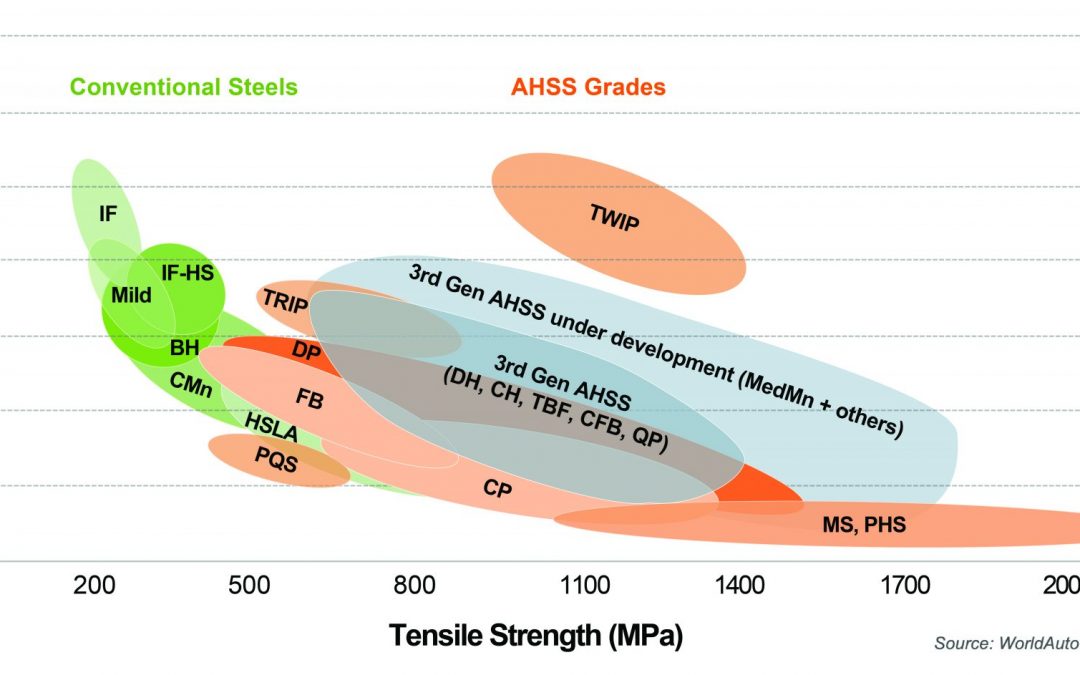

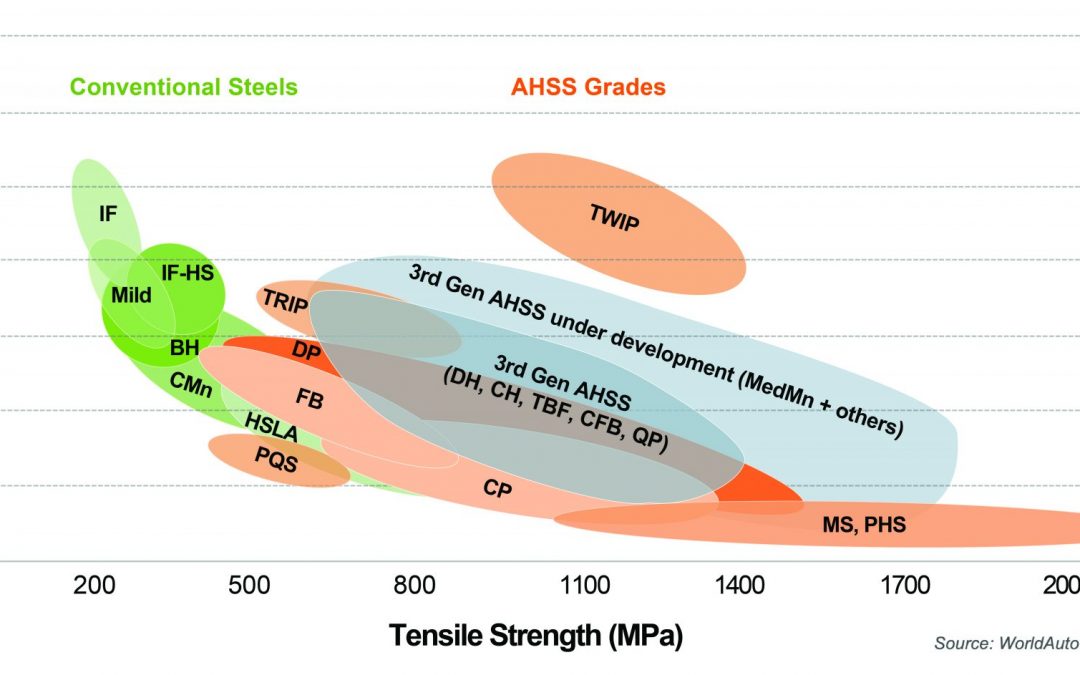

Bubble chart. Banana diagram. Steel strength ductility diagram—it’s been called a lot of things over the years. But the 2021 chart shown in Figure 1 is the subject of hundreds of requests for use we receive from engineers and students all over the world and appears in thousands of presentations and papers. Because of that, we periodically update it to make sure it reflects the most current picture of both commercially available, as well as emerging steel grades. In this blog, we are providing our updated GFD for download as well as definitions of steel classifications, as agreed to by our member companies.

Figure 1: The 2021 Global Formability Diagram comparing strength and elongation of current and emerging steel grades.

Steel Classifications

There are different ways to classify automotive steels. One is a metallurgical designation providing some process information. Common designations include lower-strength steels (interstitial-free and mild steels); conventional high strength steels, such as bake hardenable and high-strength, low-alloy steels (HSLA); and Advanced High-Strength Steels (AHSS) such as dual phase and transformation-induced plasticity steels. Additional higher strength steels include press hardening steels and steels designed for unique applications that have improved edge stretch and stretch bending characteristics.

A second classification method important to part designers is strength of the steel. This document will use the general terms HSLA and AHSS to designate all higher strength steels. The principal difference between conventional HSLA steels and AHSS is their microstructure. Conventional HSLA steels are single-phase ferritic steels with a potential for some pearlite in C-Mn steels.

AHSS are primarily steels with a multiphase microstructure containing one or more phases other than ferrite, pearlite, or cementite – for example martensite, bainite, austenite, and/or retained austenite in quantities sufficient to produce unique mechanical properties. Some types of AHSS have a higher strain hardening capacity resulting in a strength-ductility balance superior to conventional steels. Other types have ultra-high yield and tensile strengths and show a bake hardening behavior.

What are 3rd Gen Steels?

Third Generation, or 3rd Gen, AHSS builds on the previously developed 1st Gen AHSS (DP, TRIP, CP, MS, and PHS) and 2nd Gen AHSS (TWIP), with global commercialization starting around 2020. Third Gen AHSS are multi-phase steels engineered to develop enhanced formability as measured in tensile, sheared edge, and/or bending tests. Typically, these steels rely on retained austenite in a bainite or martensite matrix and potentially some amount of ferrite and/or precipitates, all in specific proportions and distributions, to develop these enhanced properties.

Graphical Presentation

Generally, elongation (a measure of ductility) decreases as strength increases. Plotting elongation on the vertical axis and strength on the horizontal axis leads to a graph starting in the upper left (high elongation, lower strength) and progressing to the lower right (lower elongation, higher strength). When considering conventional steels and the first generation of advanced high strength steels, this shape led to the colloquial description of calling this the banana diagram.

With the continued development of advanced steel options, it is no longer appropriate to describe the plethora of options as being in the shape of a banana. Instead, with new grades filling the upper right portion of Figure 1, perhaps it is more accurate to describe this as the football diagram as the options now start to fall into the shape of an American or Rugby Football. Officially, it is known as the steel Global Formability Diagram.

Even this approach has its limitations. Elongation is only one measure of ductility. Other ductility parameters are increasingly important with AHSS grades, such as hole expansion and bendability. There are several other approaches that have been proposed by experts around the world. Have a look at our Defining Steels article, from which this article was drawn, to learn more about them. You will also find within Defining Steels a detailed explanation of the nomenclature used throughout the Guidelines to define steels. If you have questions, please use the Comments tool below or on the Defining Steels page.

Download the GFD

Because of its popularity, we provide high resolution image files of the GFD here for your download and use. Please source it “Courtesy of WorldAutoSteel” in your papers and presentations. We are happy for you to use it. If you require our signed permission, please write us at steel@worldautosteel.org. We’ll respond quickly.

* The Guidelines use the general terms HSLA and AHSS to designate all higher strength steels.

![Defining Steels]()

Metallurgy

Basis

There are different ways to classify automotive steels. One is a metallurgical designation providing some process information. Common designations include lower-strength steels (interstitial-free and mild steels); conventional high strength steels, such as bake hardenable and high-strength, low-alloy steels (HSLA); and Advanced High-Strength Steels (AHSS) such as dual phase and transformation-induced plasticity steels. Additional higher strength steels include press hardening steels and steels designed for unique applications that have improved edge stretch and stretch bending characteristics.

A second classification method important to part designers is strength of the steel. This document will use the general terms HSLA and AHSS to designate all higher strength steels. The principal difference between conventional HSLA steels and AHSS is their microstructure. Conventional HSLA steels are single-phase ferritic steels with a potential for some pearlite in C-Mn steels. AHSS are primarily steels with a multiphase microstructure containing one or more phases other than ferrite, pearlite, or cementite – for example martensite, bainite, austenite, and/or retained austenite in quantities sufficient to produce unique mechanical properties. Some types of AHSS have a higher strain hardening capacity resulting in a strength-ductility balance superior to conventional steels. Other types have ultra-high yield and tensile strengths and show a bake hardening behavior.

AHSS include all martensitic and multiphase steels having a minimum specified tensile strength of at least 440 MPa. Those steels with very high minimum specified tensile strength are sometimes referred to as Ultra High Strength Steels (UHSS). Several companies choose 980 MPa as the threshold where “Ultra” high strength begins, while others use higher thresholds of 1180 MPa or 1270 MPa. There is no generally accepted definition among the producers or users of the product. The difference between AHSS and UHSS is in terminology only – they are not separate products. The actions taken by the manufacturing community to form, join, or process is ultimately a function of the steel grade, thickness, and mechanical properties. Whether these steels are called “Advanced” or “Ultra” does not impact the technical response.

Third Generation, or 3rd Gen, AHSS builds on the previously developed 1st Gen AHSS (DP, TRIP, CP, MS, and PHS) and 2nd Gen AHSS (TWIP), with global commercialization starting around 2020. 3rd Gen AHSS are multi-phase steels engineered to develop enhanced formability as measured in tensile, sheared edge, and/or bending tests. Typically, these steels rely on retained austenite in a bainite or martensite matrix and potentially some amount of ferrite and/or precipitates, all in specific proportions and distributions, to develop these enhanced properties.

Nomenclature

Historically, HSLA steels were described by their minimum yield strength. Depending on the region, the units may have been ksi or MPa, meaning that HSLA 50 and HSLA 340 both describe a High Strength Low Alloy steel with a minimum yield strength of 50 ksi = 50,000 psi ≈ 340 MPa. Although not possible to tell from this syntax, many of the specifications stated that the minimum tensile strength was 70 MPa to 80 MPa greater than the minimum yield strength.

Development of the initial AHSS grades evolved such that they were described by their metallurgical approach and minimum tensile strength, such as using DP590 to describe a dual phase steel with 590 MPa tensile strength. Furthermore, when Advanced High Strength Steels were first commercialized, there was often only one option for a given metallurgical type and tensile strength level. Now, for example, there are multiple distinct dual phase grades with a minimum 980 MPa tensile strength, each with different yield strength or formability.

To highlight these different characteristics throughout this website, each steel grade is identified by whether it is hot rolled or cold rolled, minimum yield strength (in MPa), minimum tensile strength (in MPa), and metallurgical type. Table 1 lists different types of steels.

Table 1: Different Types of Steels and Associated Abbreviations.

As an example, CR-500Y780T-DP describes a cold rolled dual phase steel with 500 MPa minimum yield strength and 780 MPa minimum ultimate tensile strength. There is also another grade with the same minimum UTS, but lower yield strength: CR440Y780T-DP. If the syntax is simply DP780, the reader should assume either that the referenced study did not distinguish between the variants or that the issues described in that section applies to all variants of a dual phase steel with a minimum 780 MPa tensile strength.

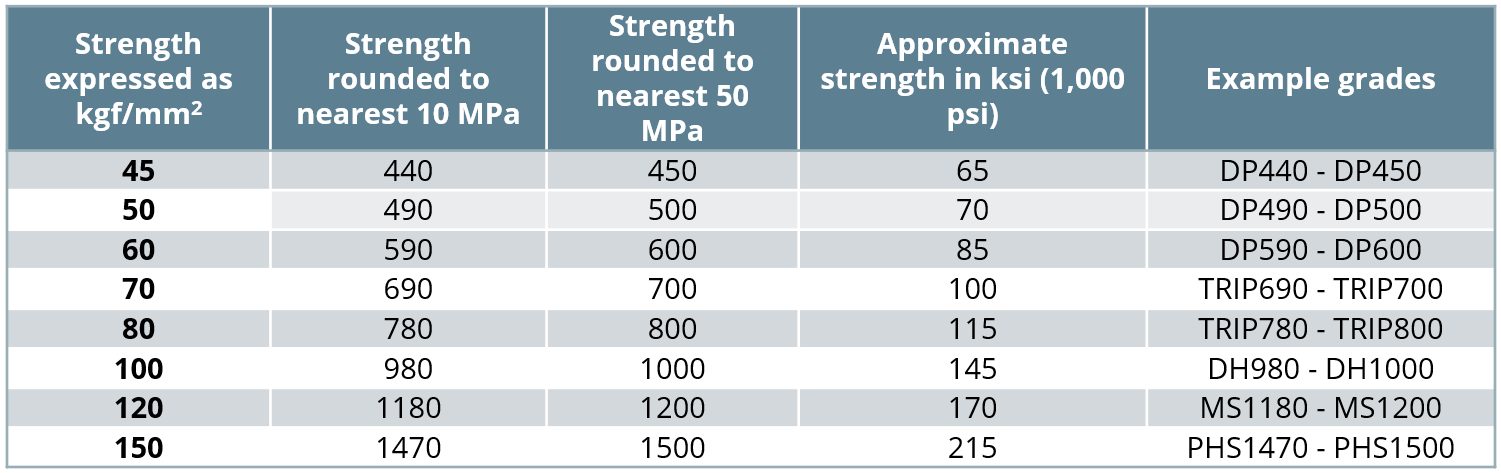

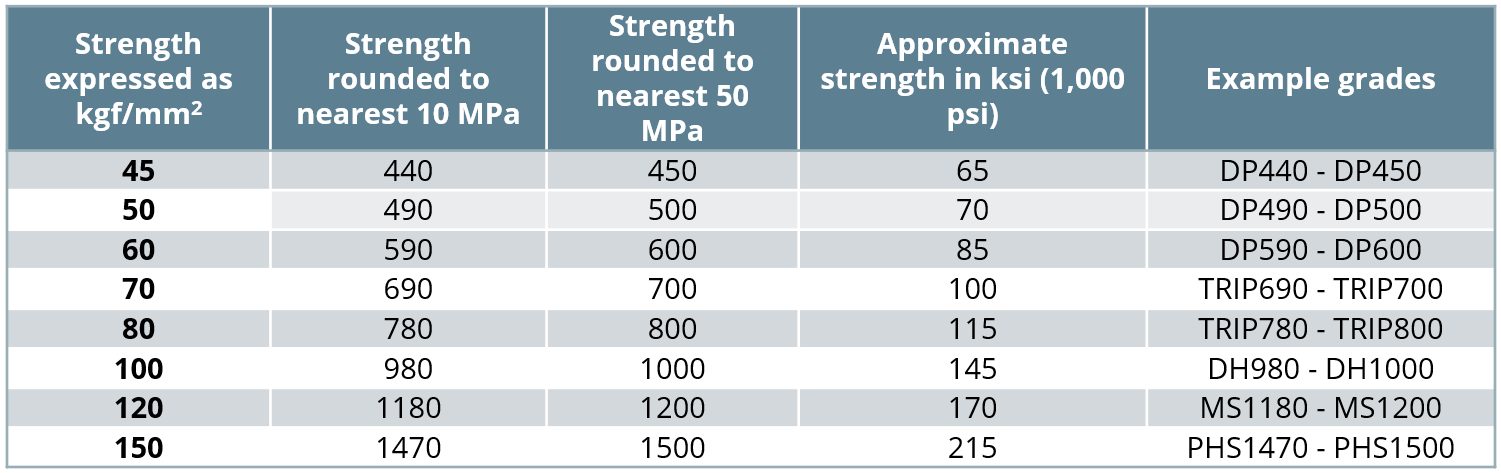

Another syntax issue is the presentation of the strength (yield or tensile), and whether it is rounded to the nearest 10 or 50 MPa. For example, consider DP980 compared with DP1000. Both forms represent essentially the same grade. In Europe, this steel may be described as having a tensile strength of 100 kgf/mm2, corresponding to 981 N/mm2 (981 MPa), and expressed as DP980. In Asia, the steel may be referred to as 100K (an abbreviation for 100 kgf/mm2). In other parts of the world, it may be rounded to nearest 50 MPa, as DP 1000. This naming approach applies to many grades, with some shown in Table 2. In some cases, although the OEM specification may list the steel as DP800 (for example), the minimum tensile strength requirement may still be 780 MPa. Furthermore, independent of the chosen naming syntax, the steel company will supply to the actual specification requirements, and will use different process controls to meet a 780 MPa minimum compared with an 800 MPa minimum.

Table 2: Syntax Related to AHSS Strength Levels

Press hardening steels sometimes require a different syntax. Some OEMs will use a similar terminology as described above. For example: CR-950Y1300T-PH (PH stands for Press Hardenable or Press Hardened) or CR-950Y1300T-MB (MB stands for Manganese-Boron steel) can describe the same cold rolled press hardening steel with 950 MPa minimum yield strength and 1300 MPa minimum tensile strength after completing the press hardening operation. Other specifications may show suffixes which highlight the forming process used, such as -DS for direct hot stamping, -IS for indirect hot stamping and MS for a multi-step process. Furthermore, sources may describe this product focused on its typical tensile strength as PHS1500T. The abbreviation PQS (Press Quenched Steel) is typically used for grades that do not harden after hot stamping. These may be noted as PQS450 and PQS550, where the numbers stand for the approximate minimum tensile strength after the hot stamping cycle (see the section on Grades With Higher Ductility on the linked page).

Graphical Presentation

Generally, elongation (a measure of ductility) decreases as strength increases. Plotting elongation on the vertical axis and strength on the horizontal axis leads to a graph starting in the upper left (high elongation, lower strength) and progressing to the lower right (lower elongation, higher strength). This shape led to the colloquial description of calling this the banana diagram.

Figure 1: A generic “banana” diagram comparing strength and elongation.

With the continued development of advanced steel options, it is no longer appropriate to describe the plethora of options as being in the shape of a banana. Instead, with new grades filling the upper right portion (see Figure 2), perhaps it is more accurate to describe this as the football diagram as the options now start to fall into the shape of an American or Rugby Football. Officially, it is known as the steel Global Formability Diagram.

Even this approach has its limitations. Elongation is only one measure of ductility. Other ductility parameters are increasingly important with AHSS grades, such as hole expansion and bendability. BillurB-61 proposed a diagram comparing the bend angle determined from the VDA238-100 testV-4 with the yield strength for various press hardened and press quenched steels.

Figure 3: VDA Bending Angle typically decreases with increasing yield strength of PHS/PQS grades.B-61

Figure 4 shows a local/global formability map sometimes referred to as the Hance Diagram named after the researcher who proposed it.H-16 This diagram combines measures of local formability (characterized by true fracture strain) and global formability (characterized by uniform elongation), providing insight on different characteristics associated with many steel grades and helping with application-specific material grade selection. For example, if good trim conditions still create edge splits, selecting materials higher on the vertical axis may help address the edge-cracking problems. Likewise, global formability necking or splitting issues can be solved by using grades further to the right on the horizontal axis.

Figure 4: The Local/Global Formability Map combines measures of local formability (true fracture strain) and global formability (uniform elongation) to highlight the relative characteristics of different grades. In this version from Citation D-12, the colors distinguish different options at each tensile strength level.

Grade Portfolio

Previous AHSS Application Guidelines showcased a materials portfolio driven by the FutureSteelVehicle (FSV) program, with more than twenty new grades of AHSS acknowledged as commercially available by 2020. The AHSS materials portfolio continues to grow, as the steel industry responds to requirements for high strength, lightweight steels. Table 3 reflects available AHSS grades as well as grades under development and nearing commercial application. The Steel Grades page provides details about these grades and their applications.

Table 3: Commercially available AHSS Grades and grades under development for near-term application. Grade names shown in Italicized Bold were available in FutureSteelVehicle. For all but PQS/PHS, Grade Name indicates the minimum yield strength, minimum tensile strength, and the type of AHSS. The min EL column indicates a typical minimum total elongation value, which may vary based on test sample shape, gauge length, and thickness. PQS/PHS grade name indicates nominal tensile strength.

Global automakers create steel specification criteria suited for their vehicle targets, manufacturing infrastructure, and other constraints. Although similar specifications exist at other companies, perfect overlap of all specifications is unlikely. Global steelmakers have different equipment, production capabilities, and commercial availability.

Minimum or typical mechanical properties shown on this web page and throughout this site illustrates the broad range of AHSS grades that may be available. Properties of hot rolled steels can differ from cold rolled steels. Coating processes like hot dip galvanizing or galvannealing subjects the base metal to different thermal cycles that affect final properties. Test procedures and requirements have a regional or OEM influence, such as preference to using tensile test gauge length of 50 mm or 80 mm, or specifying minimum property values parallel or perpendicular to the rolling direction.

Steel users must communicate directly with individual steel companies to determine specific grade availability and the specific associated parameters and properties, such as:

- Chemical composition specifications,

- Mechanical properties and ranges,

- Thickness and width capabilities,

- Hot-rolled, cold-rolled, and coating availability,

- Joining characteristics.

1stGen AHSS, 3rdGen AHSS, AHSS, Steel Grades

topofpage

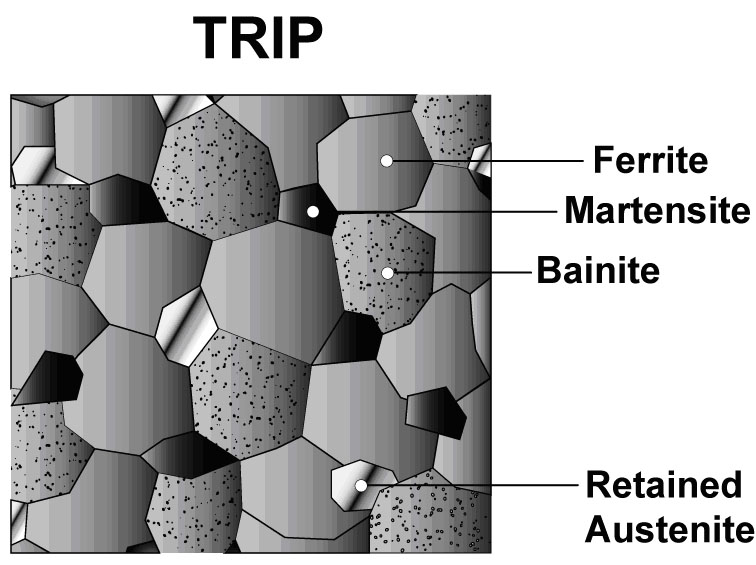

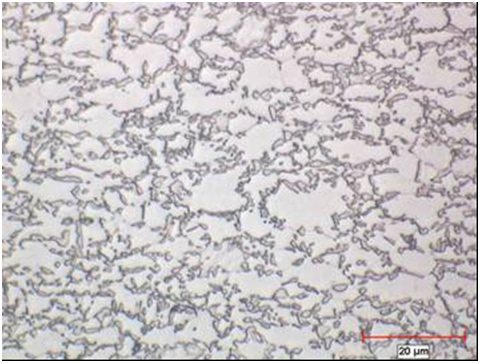

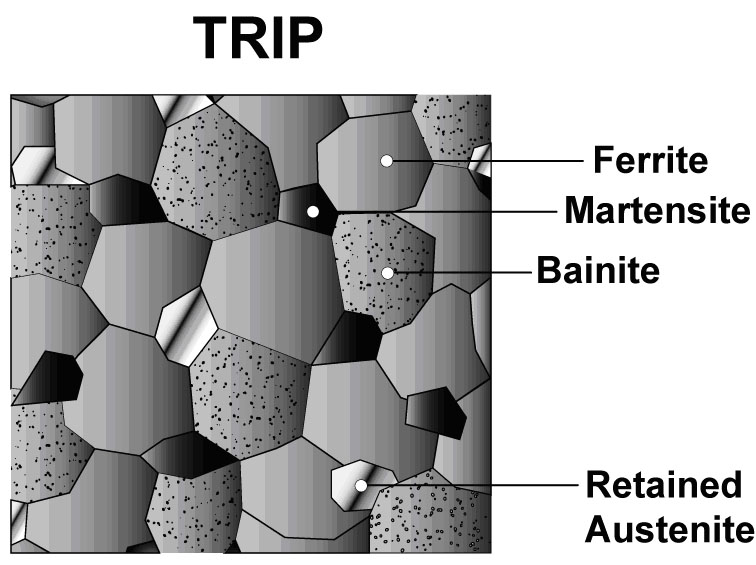

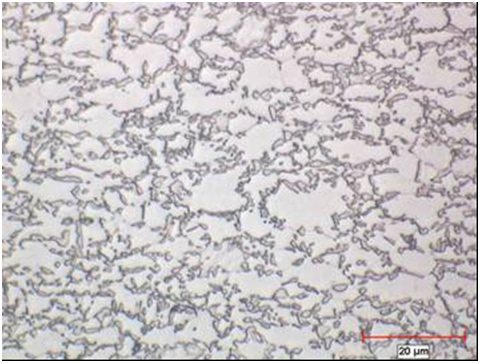

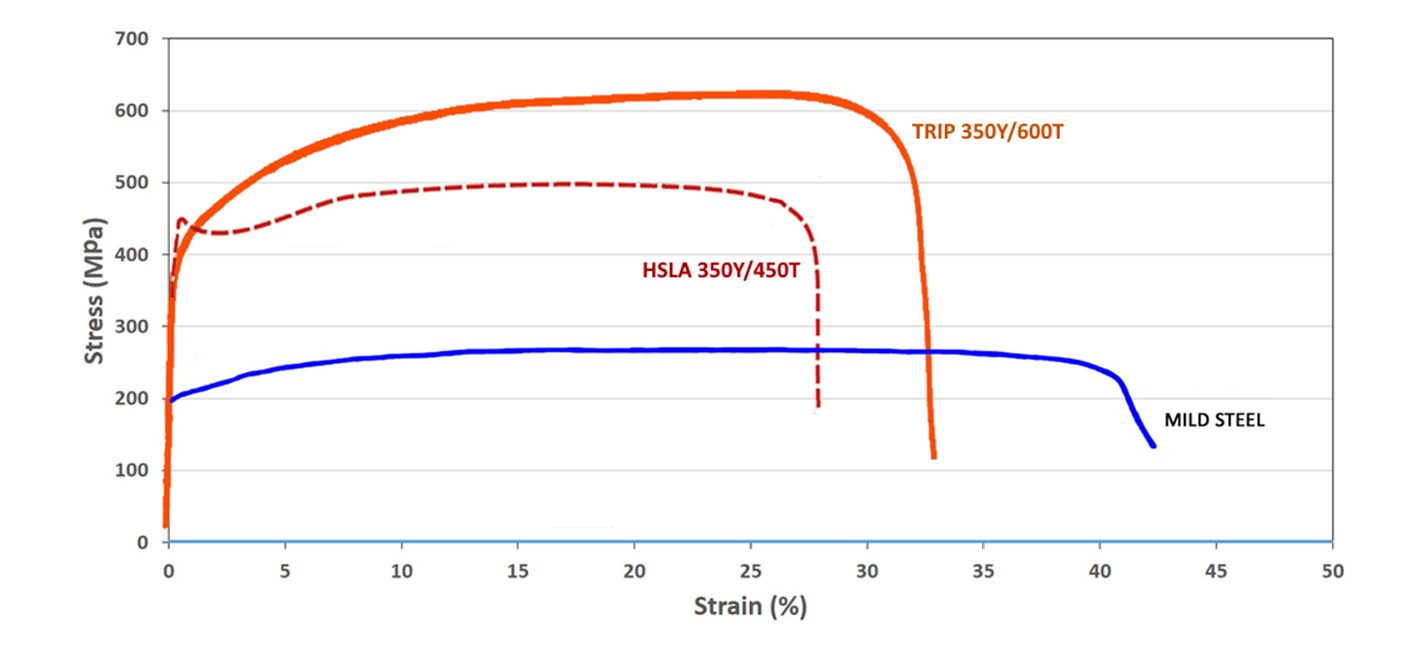

The microstructure of Transformation Induced Plasticity (TRIP) steels contains a matrix of ferrite, with retained austenite, martensite, and bainite present in varying amounts. Production of TRIP steels typically requires the use of an isothermal hold at an intermediate temperature, which produces some bainite. Higher silicon and carbon content of TRIP steels result in significant volume fractions of retained austenite in the final microstructure. Figure 1 shows a schematic of TRIP steel microstructure, with Figure 2 showing a micrograph of an actual sample of TRIP steel. Figure 3 compares the engineering stress-strain curve for HSLA steel to a TRIP steel curve of similar yield strength.

Figure 1: Schematic of a TRIP steel microstructure showing a matrix of ferrite, with martensite, bainite and retained austenite as the additional phases.

Figure 2: Micrograph of Transformation Induced Plasticity steel.

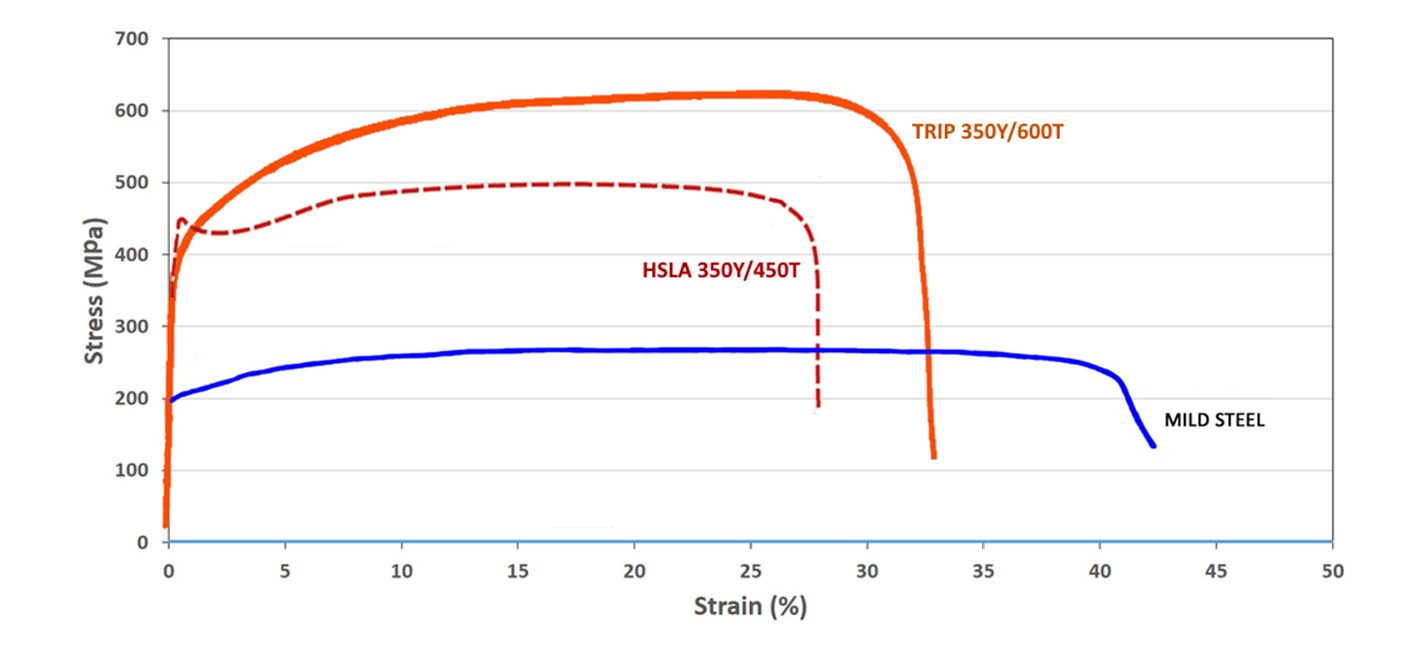

Figure 3: A comparison of stress strain curves for mild steel, HSLA 350/450, and TRIP 350/600.K-1

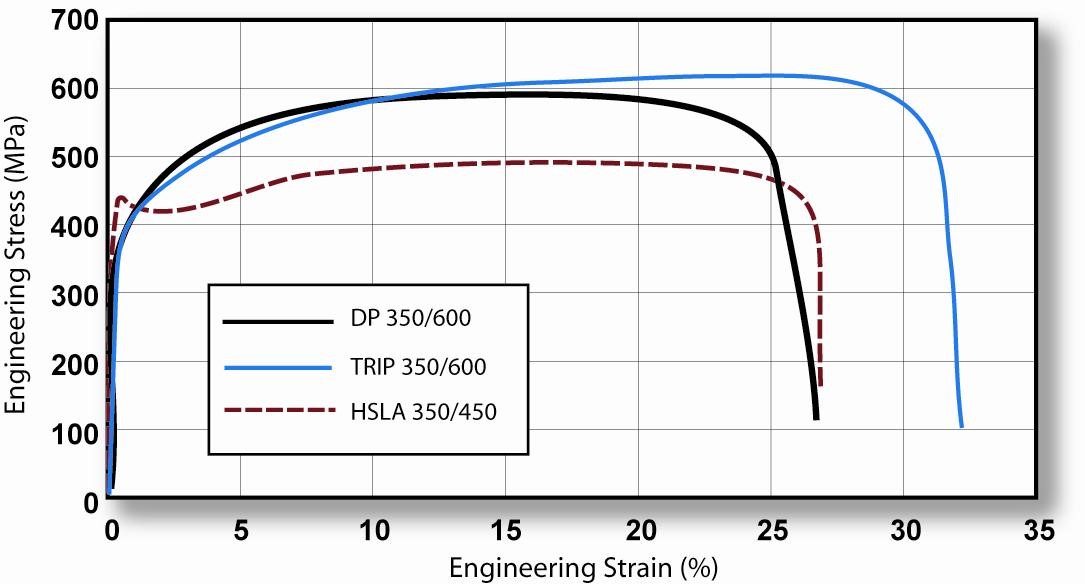

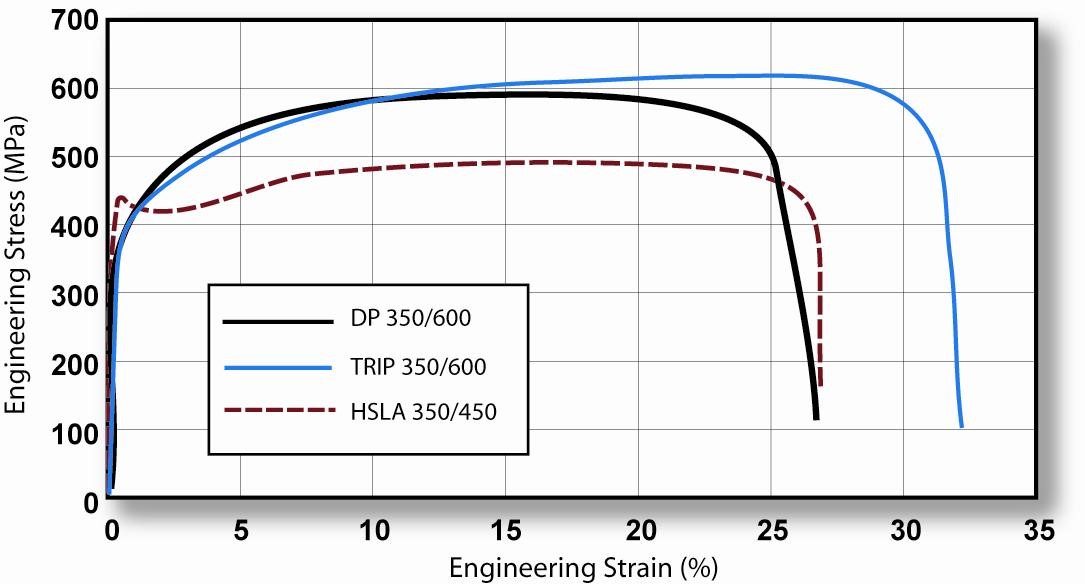

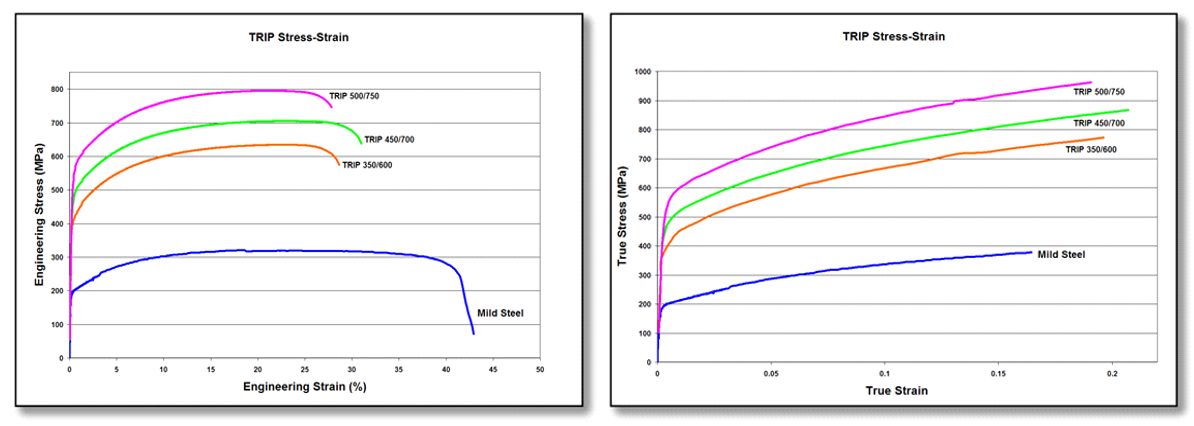

During deformation, the dispersion of hard second phases in soft ferrite creates a high work hardening rate, as observed in the DP steels. However, in TRIP steels the retained austenite also progressively transforms to martensite with increasing strain, thereby increasing the work hardening rate at higher strain levels. This is known as the TRIP Effect. This is illustrated in Figure 4, which compares the engineering stress-strain behavior of HSLA, DP and TRIP steels of nominally the same yield strength. The TRIP steel has a lower initial work hardening rate than the DP steel, but the hardening rate persists at higher strains where work hardening of the DP begins to diminish. Additional engineering and true stress-strain curves for TRIP steel grades are shown in Figure 5.

Figure 4: TRIP 350/600 with a greater total elongation than DP 350/600 and HSLA 350/450. K-1

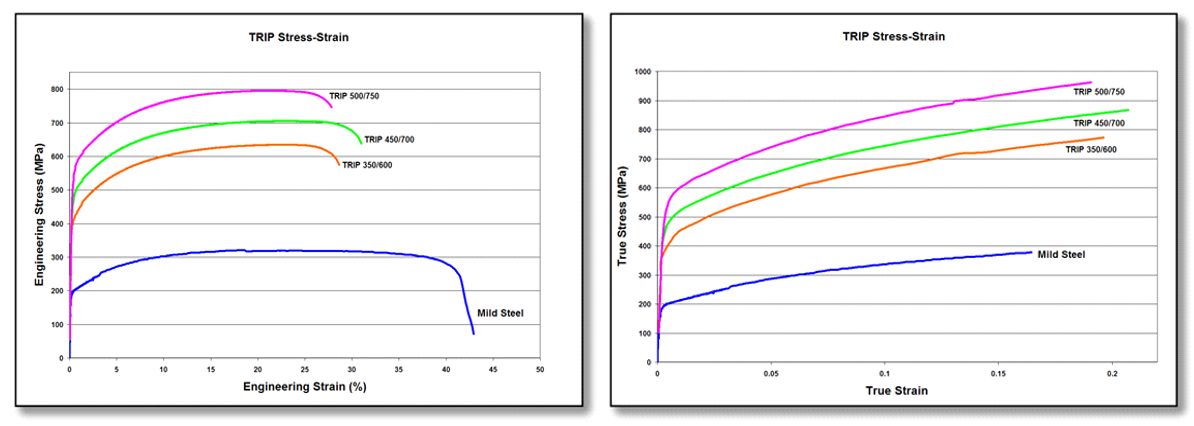

Figure 5: Engineering stress-strain (left graphic) and true stress-strain (right graphic) curves for a series of TRIP steel grades. Sheet thickness: TRIP 350/600 = 1.2mm, TRIP 450/700 = 1.5mm, TRIP 500/750 = 2.0mm, and Mild Steel = approx. 1.9mm. V-1

The strain hardening response of TRIP steels are substantially higher than for conventional HSS, resulting in significantly improved formability in stretch deformation. This response is indicated by a comparison of the n-value for the grades. The improvement in stretch formability is particularly useful when designers take advantage of the improved strain hardening response to design a part utilizing the as-formed mechanical properties. High n-value persists to higher strains in TRIP steels, providing a slight advantage over DP in the most severe stretch forming applications.

Austenite is a higher temperature phase and is not stable at room temperature under equilibrium conditions. Along with a specific thermal cycle, carbon content greater than that used in DP steels are needed in TRIP steels to promote room-temperature stabilization of austenite. Retained austenite is the term given to the austenitic phase that is stable at room temperature.

Higher contents of silicon and/or aluminum accelerate the ferrite/bainite formation. These elements assist in maintaining the necessary carbon content within the retained austenite. Suppressing the carbide precipitation during bainitic transformation appears to be crucial for TRIP steels. Silicon and aluminum are used to avoid carbide precipitation in the bainite region.

The carbon level of the TRIP alloy alters the strain level at which the TRIP Effect occurs. The strain level at which retained austenite begins to transform to martensite is controlled by adjusting the carbon content. At lower carbon levels, retained austenite begins to transform almost immediately upon deformation, increasing the work hardening rate and formability during the stamping process. At higher carbon contents, retained austenite is more stable and begins to transform only at strain levels beyond those produced during forming. At these carbon levels, retained austenite transforms to martensite during subsequent deformation, such as a crash event.

TRIP steels therefore can be engineered to provide excellent formability for manufacturing complex AHSS parts or to exhibit high strain hardening during crash deformation resulting in excellent crash energy absorption.

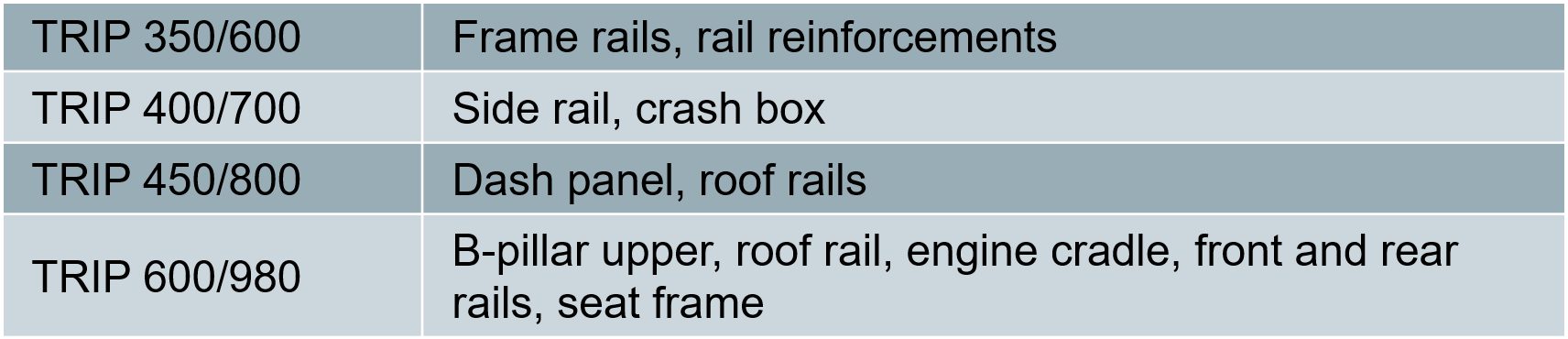

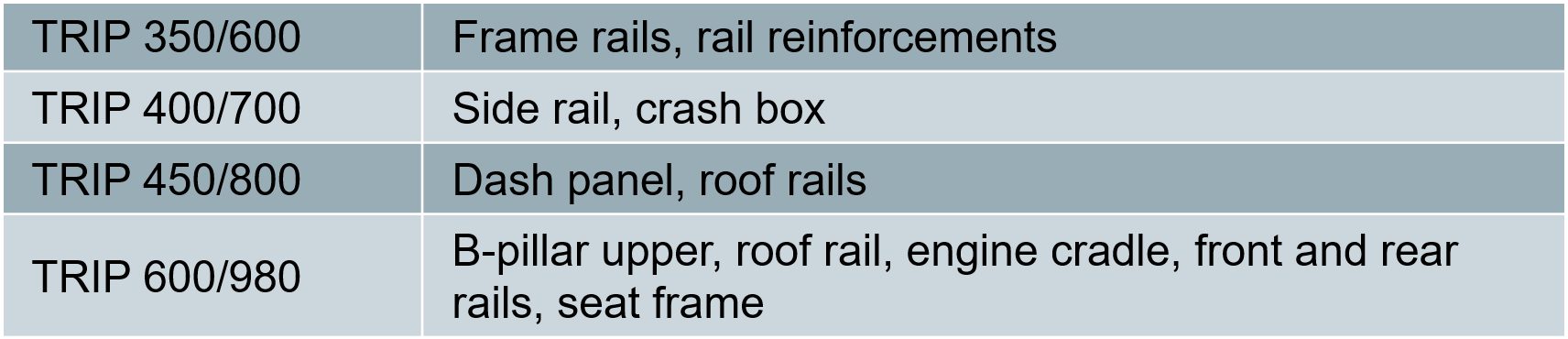

The additional alloying requirements of TRIP steels degrade their resistance spot-welding behavior. This can be addressed through weld cycle modification, such as the use of pulsating welding or dilution welding. Table 1 provides a list of current production grades of TRIP steels and example automotive applications:

Table 1: Current Production Grades Of TRIP Steels And Example Automotive Applications.

Some of the specifications describing uncoated cold rolled 1st Generation transformation induced plasticity (TRIP) steel are included below, with the grades typically listed in order of increasing minimum tensile strength and ductility. Different specifications may exist which describe hot or cold rolled, uncoated or coated, or steels of different strengths. Many automakers have proprietary specifications which encompass their requirements.

• ASTM A1088, with the terms Transformation induced plasticity (TRIP) steel Grades 690T/410Y and 780T/440YA-22

• JFS A2001, with the terms JSC590T and JSC780TJ-23

• EN 10338, with the terms HCT690T and HCT780TD-18

• VDA 239-100, with the terms CR400Y690T-TR and CR450Y780T-TRV-3

• SAE J2745, with terms Transformation Induced Plasticity (TRIP) 590T/380Y, 690T/400Y, and 780T/420YS-18

Transformation Induced Plasticity Effect

Austenite is not stable at room temperature under equilibrium conditions. An austenitic microstructure is retained at room temperature with the combined use of a specific chemistry and controlled thermal cycle. Deformation from sheet forming provides the necessary energy to allow the crystallographic structure to change from austenite to martensite. There is insufficient time and temperature for substantial diffusion of carbon to occur from carbon-rich austenite, which results in a high-carbon (high strength) martensite after transformation. Transformation to high strength martensite continues as deformation increases, as long as retained austenite is still available to be transformed.

Alloys capable of the TRIP effect are characterized by a high ductility – high strength combination. Such alloys include 1st Gen AHSS TRIP steels, as well as several 3rd Gen AHSS grades like TRIP-Assisted Bainitic Ferrite, Carbide Free Bainite, and Quench & Partition Steels.

Back to the Top