Blog, homepage-featured-top, main-blog, News

Tailor-welded blanks (TWBs) allow the combination of different steel grades, thicknesses, and even coating types into a single blank. This results in stamping a single component with the right material in the right place for on-vehicle requirements. This technology allows the consolidation of multiple stampings into a single component.

One example is the front door inner. A two-piece design will have an inner panel and a reinforcement in the hinge area. As shown in Figure 1, a TWB front door inner incorporates a thicker front section in the hinge area and a thinner rear section for the inner panel, providing on-vehicle mass savings. This eliminates the need for additional components, reducing the tooling investment in the program. This also simplifies the assembly process, eliminating the need to spot weld a reinforcement onto the panel.

Figure 1 – Front Door Inner

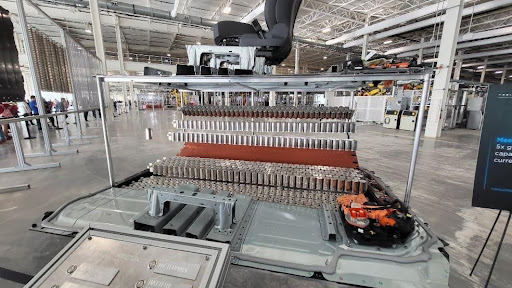

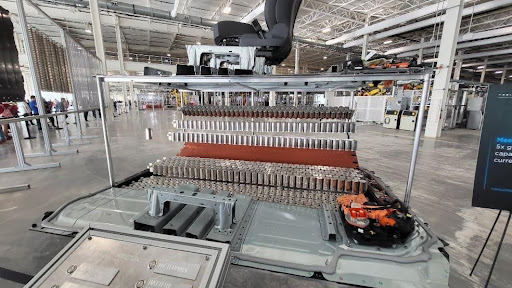

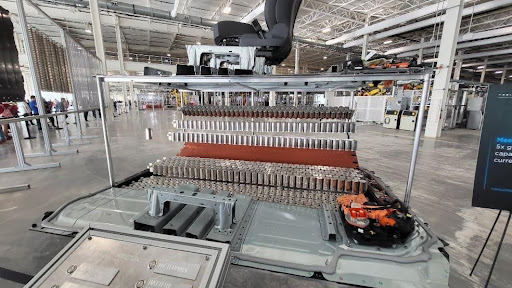

Today, large opportunities exist to consolidate components in a BEV in the battery structure. Design strategies vary from different automakers, including how the enclosure is constructed or how the battery mounts into the vehicle. The battery tray can have over 100 stamped components, including sealing surfaces, structural members, and reinforcements (Munro Live – Munro and Associates, 2023)M-68. As an idea, a battery tray perimeter could be eight pieces, four lateral and longitudinal members, and four corners. The upper and lower covers are two additional stamped components, for a total of ten stampings that make up the sealing structure of the battery tray. On a large BEV truck, that results in over 17m of external sealing surfaces.

Part consolidation in the battery structure provides cost savings in material requirements and reduced investment in required tooling. Another benefit of assembly simplification is improved quality. Fewer components mean fewer sealing surfaces, resulting in less rework in the assembly process, where every battery tray is leak-tested.

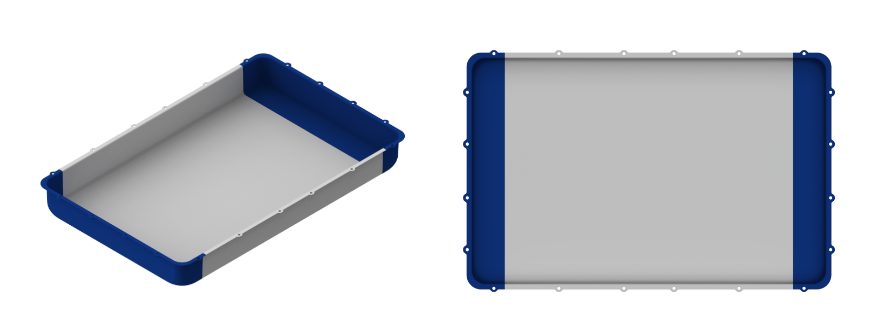

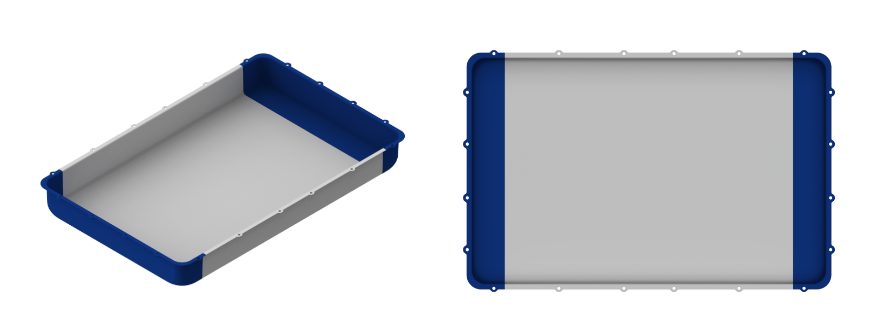

The deep-drawn battery tub is a consolidated lower battery enclosure and perimeter. This can be seen in Figure 2; a three-piece welded blank incorporates a thicker and highly formable material at the ends and in the center section, either a martensitic steel for intrusion protection or a low-cost mild steel. This one-piece deep-drawn tub reduces the number of stampings and sealing surfaces, resulting in a more optimized and efficient design when considered against a multi-piece assembly. In the previous example of a BEV truck, the deep-drawn battery tub would reduce the external sealing surface distance by 40%. To validate this concept, component level simulations of crash, intrusion, and formability were conducted. As well as a physical prototype built that was used for leak and thermal testing (Yu, 2024)Y-14 with the outcomes proving the validity of this concept, as well as developing preliminary design guidelines. Additional work is underway to increase the depth of the draw while minimizing the draft angle on the tub stamping.

Figure 2 – Deep Battery Tub

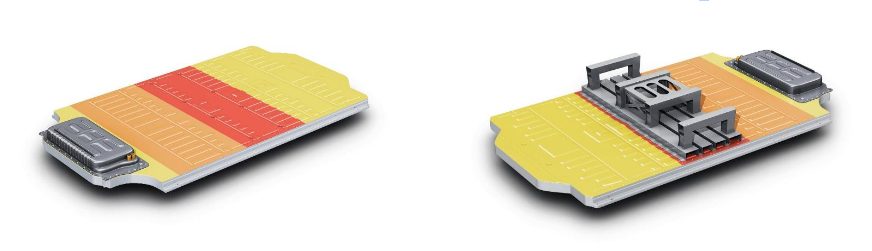

In most BEVs today, the passenger compartment has a floor structure common in an ICE vehicle. However, the BEV also has a top cover on the battery assembly that, in most cases, is the same size as the passenger compartment floor. In execution of part consolidation, the body floor and battery top cover effectively seal the same opening and can be consolidated into one component. An example is shown below, where seat reinforcements found on the vehicle floor are integrated into the battery top cover, and the traditional floor of the vehicle is removed. Advanced high-strength steels are used in different grades and thicknesses. Figure 3 and Figure 4 show what the TWB battery top cover looks like on the assembly.

Figure 3 + Figure 4 – TWB Battery Top Cover

Vehicle assembly can also be radically simplified as front seats are mounted on the battery before being installed in the vehicle as shown in Figure 5, the ergonomics of the assembly operation are improved by increased access inside the passenger compartment through the open floor.

Figure 5 – Ergonomics of the Assembly Operation

Cost mitigation is more important than ever before, with reductions in piece cost and investment and assembly costs being important. At the foundation BEVs currently have cost challenges in comparison to their ICE counterparts, however the optimization potential for the architecture remains high, specifically in part consolidation. Unique concepts such as the TWB deep-drawn battery tub and integrated floor/battery top cover are novel approaches to improve challenges faced with existing BEV designs. TWB applications throughout the body in white and closures remain relevant in BEVs, providing further part consolidation opportunities.

Thanks go to Isaac Luther for his contribution of this article to the AHSS Insights blog. Luther is a senior product engineer on the new product development team at TWB Company. TWB Company is the premier supplier of tailor-welded solutions in North America. In this role, Isaac is responsible for application development in vehicle body and frame applications and battery systems. Isaac has a Bachelor of Science in welding engineering from The Ohio State University.

Blog, homepage-featured-top, Joining, Joining Dissimilar Materials, main-blog, News, Resistance Spot Welding, Resistance Welding Processes, RSW Modelling and Performance, RSW of Dissimilar Steel

This blog is a short summary of a published comprehensive research work titled: “Peculiar Roles of Nickel Diffusion in Intermetallic Compound Formation at the Dissimilar Metal Interface of Magnesium to Steel Spot Welds” Authored by Luke Walker, Carolin Fink, Colleen Hilla, Ying Lu, and Wei Zhang; Department of Materials Science and Engineering, The Ohio State University

*****

There is an increased need to join magnesium alloys to high-strength steels to create multi-material lightweight body structures for fuel-efficient vehicles. Lightweight vehicle structures are essential for not only improving the fuel economy of internal combustion engine automobiles but also increasing the driving range of electric vehicles by offsetting the weight of power systems like batteries.

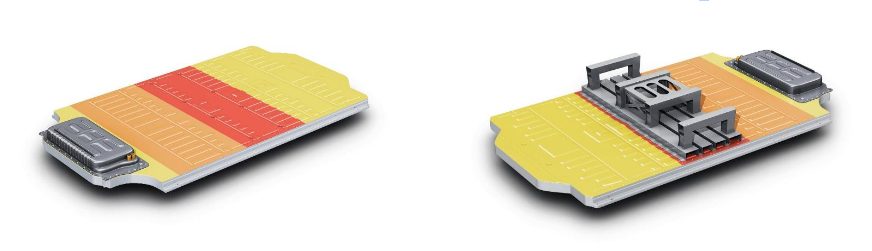

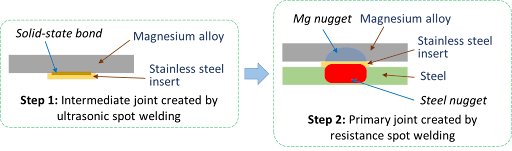

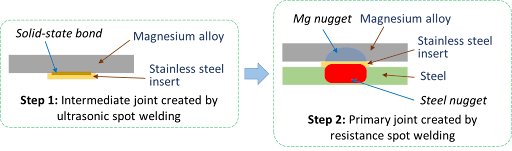

To create these structures, lightweight metals, such as magnesium (Mg) alloys, have been incorporated into vehicle designs where they are joined to high strength steels. It is desirable to produce a metallurgical bond between Mg alloys and steels using welding. However, many dissimilar metal joints form intermetallic compounds (IMCs) that are detrimental to joint ductility and strength. Ultrasonic interlayered resistance spot welding (Ulti-RSW) is a newly developed process that has been used to create strong dissimilar joints between aluminum alloys and high-strength steels. It is a two-step process where the light metal (e.g., Al or Mg alloy) is first welded to an interlayer (or insert) material by ultrasonic spot welding (USW). Ultrasonic vibration removes surface oxides and other contaminates, producing metal-to-metal contact and, consequently, a metallurgical bond between the dissimilar metals. In the second step, the insert side of the light metal is welded to steel by the standard resistance spot welding (RSW) process.

Cross-section View Schematics of Ulti-RSW Process Development

Cross-section View Schematics of Ulti-RSW Process Development

For resistance spot welding of interlayered Mg to steel, the initial schedule attempted was a simple single pulse weld schedule that was based on what was used in our previous study for Ulti-RSW of aluminum alloy to steel . However, this single pulse weld schedule was unable to create a weld between the steel sheet and the insert when joining to Mg. Two alternative schedules were then attempted; both were aimed at increasing the heat generation at the steel-insert interface. The first alternative schedule utilized two current pulses with Pulse 1, high current displacing surface coating and oxides and Pulse 2 growing the nugget. The other pulsation schedule had two equal current pulses in terms of current and welding time.

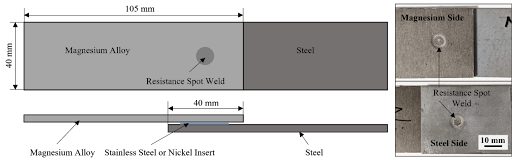

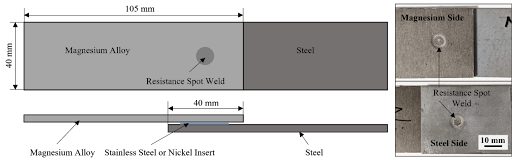

Lap shear tensile testing was used to evaluate the joint strength using the stack-up schematically, shown below. Note the images of Mg and steel sides of a weld produced by Ulti-RSW.

Lap Shear Tensile Test Geometry and the Resultant Weld Nuggets

Lap Shear Tensile Test Geometry and the Resultant Weld Nuggets

An example of a welded sample showed a distinct feature of the weld that is comprised of two nuggets separated by the insert: the steel nugget formed from the melting of steel and insert and the Mg nugget brazed onto the unmelted insert. This feature is the same as that of the Al-steel weld produced by Ulti-RSW in our previous work. Although the steel nugget has a smaller diameter than the Mg nugget, it is stronger than the latter, so the failure occurred on the Mg sheet side.

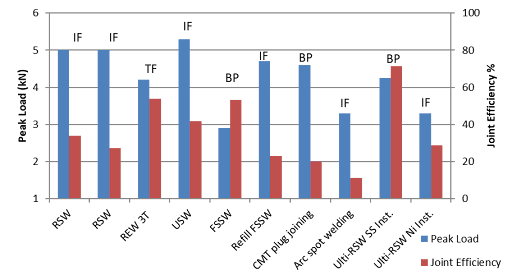

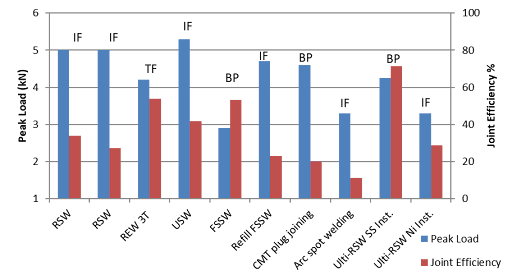

Joint strength depends on several factors, including base metal strength, sheet thickness, and nugget size, making it difficult to compare how strong a weld truly is from one process to another. To better compare the dissimilar joints created by different processes, joint efficiency, a “normalized” quantity was calculated for various processes used for dissimilar joining of Mg alloys to steels in the literature, and those results, along with the efficiencies of Ulti-RSW with inserts, are shown together below. Most of the literature studies also used AZ31 as the magnesium base metal. The ones with high joint efficiency (about 53%) in the literature are resistance element welding (REW) and friction stir spot welding (FSSW). In our study, Ulti-RSW with SS316 insert was able to reach an excellent joint efficiency of 71.3%, almost 20% higher than other processes.

Process Evaluation and Comparison

Process Evaluation and Comparison

Thanks are given to Menachem Kimchi, Associate Professor-Practice, Dept of Materials Science, Ohio State University, and Technical Editor – Joining, AHSS Application Guidelines, for this article.

Blog, main-blog, News

As robotaxi companies in the USA prepare to launch their autonomous vehicles in more cities, safety is in the spotlight again. And rightly so. Autonomous vehicle safety challenges must be addressed and with the Steel E-Motive Level 5 autonomous concept, we did that.

Many autonomous mobility service companies have relied on two factors when developing their vehicles: active safety systems which help the vehicle avoid or mitigate the extent of a crash, and a maximum vehicle speed limit, which will reduce the extent of injuries to the occupants.

But the fact is that these vehicles are going to be out in mixed-mode traffic situations. There will be accidents – however much we all attempt to do everything possible to avoid them. When we developed the Steel E-Motive (SEM) body structure concepts for fully autonomous ride-sharing electric vehicles, we agreed on two basic principles – that these vehicles would operate at high speeds (top speed of 130 kph) in mixed mode traffic conditions, and that we, therefore, needed to engineer passive safety structures that met global high-speed crash requirements to protect occupants and the battery system in these use-case conditions. In this process, we discovered that no other provider of autonomous ride-sharing electric vehicles had fully shared details of passive safety structures engineered to those same high-speed crash standards. Autonomous vehicle safety had been addressed only on a limited basis.

Fortunately, our vehicle design process benefitted from a massive portfolio of modern advanced high-strength steels (AHSS) available through member companies of WorldAutoSteel. Steel E-Motive (SEM) was developed to show how AHSS can enable sustainable, comfortable, economical, and safe ride-sharing vehicles by 2030.

The AHSS Extended Passenger Protection Zone provides excellent cabin intrusion protection and ultimately lower risk of injury. PHS provides formability for challenging geometries, and Martensitic steel (MS) provides the strength to limit intrusion.

Visit this link to download the full engineering report: Steel E-Motive

The result is one of the first robotaxis to fully detail and report compliance to global high-speed safety standards. In developing Steel E-Motive, we targeted conformity with seven US crash standards, including US NCAP (New Car Assessment Program) IIHS and FMVSS (Federal Motor Vehicle Safety Standards) front, side, and rear impact tests while also assessing performance against worldwide protocols, including NHTSA (US) Euro NCAP (European) and China’s GB 38031 standard for battery protection.

As an example, Steel E-Motive achieves the highest IIHS rating of “good.” This is particularly important as IIHS (the US-based Insurance Institute for Highway Safety) is highly regarded for its dedication to reducing deaths, injuries, and property damage from motor vehicle crashes.

Most production vehicles use new generation, advanced high-strength steels, and technologies. We had no fewer than 64 AHSS materials to select from, enabling us to choose exactly the right steel for every need and purpose in the vehicle, including safety protection. These make a car stronger, more fuel efficient, and safer.

Nearly all vehicles on the road today are made of steel because it has the broadest range of properties while being the most affordable structural material for designing safe vehicles. Steel has a unique capacity to absorb an impact, and, therefore, to diffuse crash energy. It also becomes harder when it’s crushed, which means it will become stronger on impact, retarding further penetration into the vehicle’s passenger zone.

Taking on Autonomous Vehicle Safety Challenges

Here is an outline of how we designed steel’s benefits into the Steel E-Motive (SEM) concept when considering front and side crashes.

SEM features a high-strength front protection zone, which reacts to the crush loads and minimizes intrusion for the occupants in front crashes. The crush zones have been engineered to decelerate the vehicle progressively. The longitudinal mid rails, featuring tailor-welded blanks fabricated with Dual Phase steels, are tuned to give a lower deceleration pulse into the passenger cabin to minimize injury threat. The side crush rails are designed to minimize intrusion into the cabin for occupant protection. Finally, a novel design geometry and Press Hardened Steels enable the new glance beam architecture to force the vehicle off of the Small Offset barrier; the resulting “glance-off” achieves significantly reduced crash energy and pulse into the passenger cabin.

When considering side crashes, we engineered the body structure for the IIHS 60kph deformable barrier test and 30kph side pole test, assessing both occupant and battery protection and achieving the IIHS “good” performance rating. Our side structures are comprised of a large one-piece tailor-welded door ring fabricated with press hardened steels, the TRIP steel B pillar housed in the side scissor doors, and a roll-formed hexagon rocker beam fabricated with Dual Phase steel.

These attain a very safe design, giving good levels of protection for both the occupants and battery modules, exceeding 30mm intrusion clearance at critical measurement points.

SEM was also engineered for rear crash and roof crush, and once again, the robust steel-intensive architecture exceeds crash standard requirements.

Electric-powered vehicle sales are accelerating, reflecting industry investment, and will soon achieve market domination from the combustion engine. In megacities, where congestion, pollution, and exorbitant vehicle ownership costs reign, Autonomous cars will replace drivers, and ride-sharing will become the norm. As we look into the future and recognize the need for these vehicles to offer comfortable, safe, affordable, and sustainable transportation, we will still be designing them by harnessing the unique properties of steel.

Visit this link to download the full engineering report: Steel E-Motive

AHSS, Blog, homepage-featured-top, Joining, main-blog, News, Resistance Spot Welding, RSW of Dissimilar Steel, Steel Grades, Tool & Die Professionals

Urbanization and waning interest in vehicle ownership point to new transport opportunities in megacities around the world. Mobility as a Service (MaaS) – characterized by autonomous, ride-sharing-friendly EVs – can be the comfortable, economical, sustainable transport solution of choice thanks to the benefits that today’s steel offers.

The WorldAutoSteel organization is working on the Steel E-Motive program, which delivers autonomous ride-sharing vehicle concepts enabled by Advanced High-Strength Steel (AHSS) products and technologies.

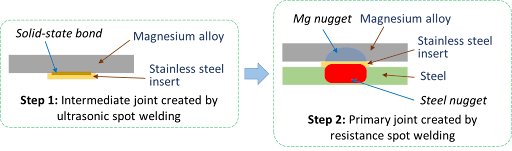

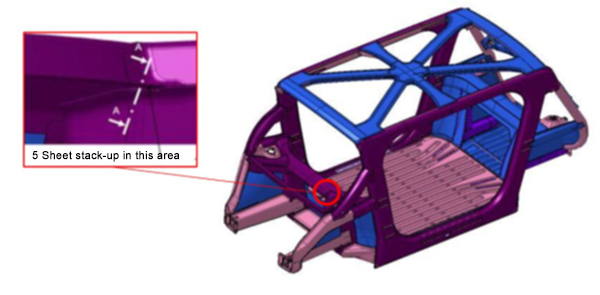

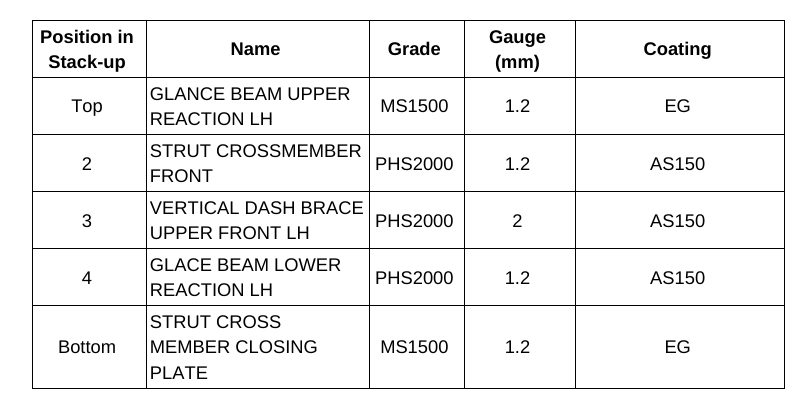

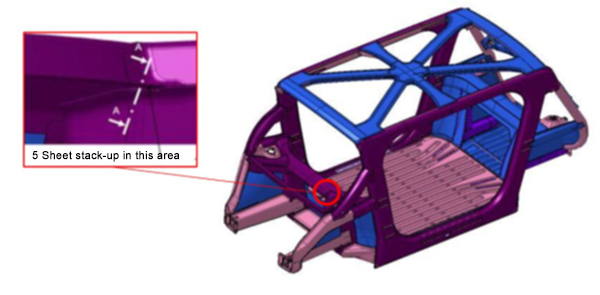

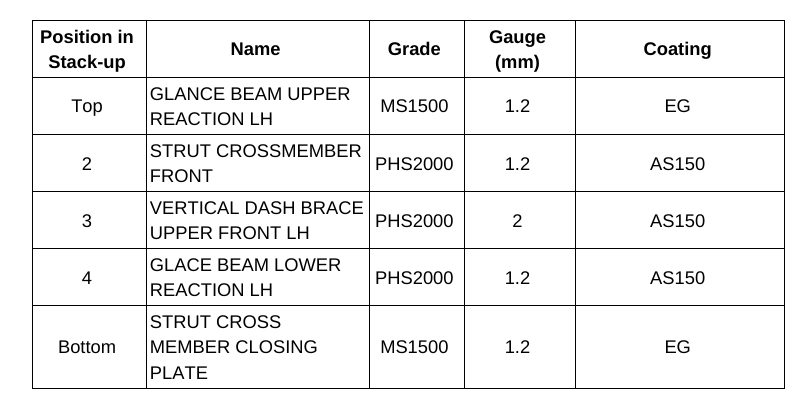

The Body structure design for this vehicle is shown in Figure 1. It also indicates the specific joint configuration of 5 layers AHSS sheet stack-up as shown in Table 1. Resistance spot welding parameters were developed to allow this joint to be made by a single weld. (The previous solution for this welded joint is to create one spot weld with the bottom 3 sheets indicated in the table and a second weld to join the top 2 sheets, combining the two-layer groups to 5T stack-up.)

NOTE: Click this link to read a previous AHSS Insights blog that summarizes development work and recommendations for resistance spot welding 3T and 4T AHSS stack-ups: https://bit.ly/42Alib8

Table 1. Provided materials organized in stack-up formation showing part number, name, grade, gauge in mm, and coating type. Total thickness = 6.8 mm

The same approach of utilizing multiple current pulses with short cool time in between the pulses was shown to be most effective in this case of 5T stack-up. It is important to note that in some cases, the application of a secondary force was shown to be beneficial, however, it was not used in this example.

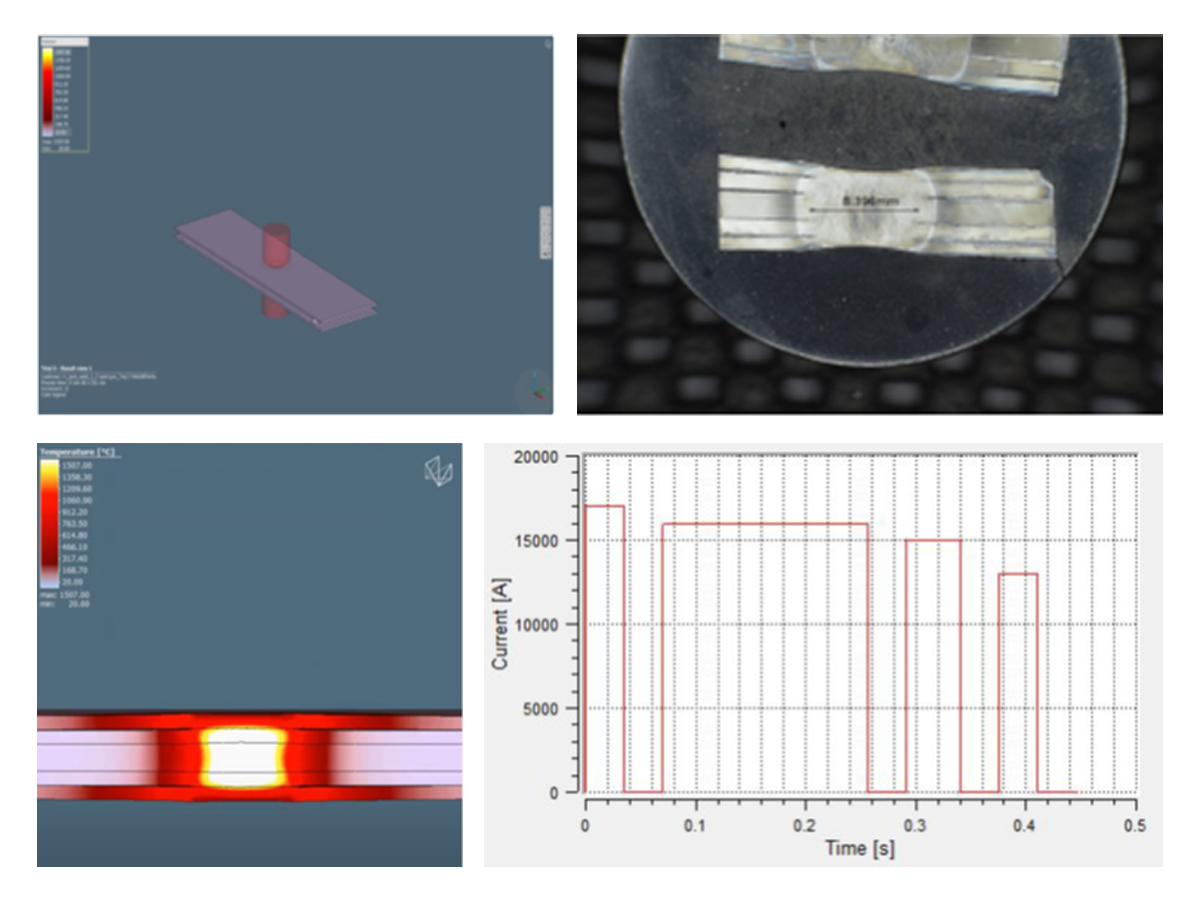

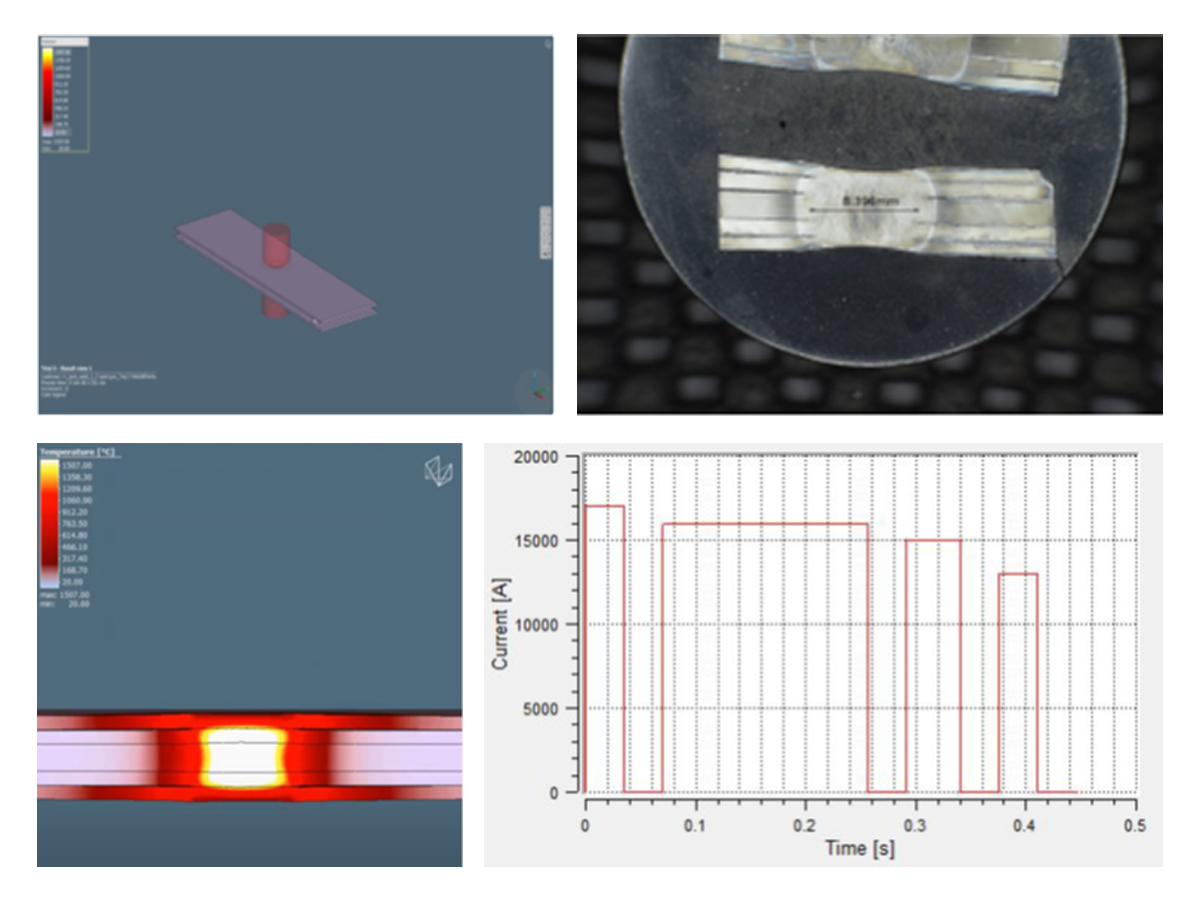

To establish initial welding parameters simulations were conducted using the Simufact software by Hexagon. As shown in Figure 2, the final setup included a set of welding electrodes that clamped the 5-layer AHSS stack-up. Several simulations were created with a designated set of welding parameters of current, time, number of pulses, and electrode force.

Figure 2. Example of simulation and experimental results showing acceptable 5T resistance spot weld (Meets AWS Automotive specifications)

Thanks is given to Menachem Kimchi, Associate Professor-Practice, Dept of Materials Science, Ohio State University and Technical Editor – Joining, AHSS Application Guidelines, for this article.

1stGen AHSS, 2ndGen AHSS, 3rdGen AHSS, AHSS, Blog, homepage-featured-top, main-blog, News, Production Managers, Steel Grades, Tool & Die Professionals

This month’s blog was contributed by Peter Ulintz, Precision Metalforming Association. This content originally appeared in the September 2023 issue of MetalForming Magazine under the title “Stronger AHSS Knowledge Required for Metal Stampers” and has been reproduced with the permission of MetalForming Magazine.

Metal stampers and die shops experienced with mild and HSLA steels often have problems making parts from AHSS grades. The higher initial yield strengths and increased work hardening of these steels can require as much as four times the working loads of mild steel. Some AHSS grades also have hardness levels approaching the dies used to form them.

Dies Get Tougher

Metal stampers and die shops experienced with mild and HSLA steels often have problems making parts from AHSS grades. The higher initial yield strengths and increased work hardening of these steels can require as much as four times the working loads of mild steel. Some AHSS grades also have hardness levels approaching the dies used to form them.

The higher stresses required to penetrate higher-strength materials require increased punch-to-die clearances compared to mild steels and HSLA grades. Why? This clearance acts as leverage to bend and break the slug out of the sheet metal. Stronger materials need longer levers to bend the slug. The required clearance is a function of the steel grade and tensile strength, and sheet thickness.

Increasing cutting clearance can result in punch cracking and head breakage due to higher snapthrough loads and reverse-unloading forces within the die. Adding shear angles to the punch face helps reduce punch forces and reverse unloading.

Tight-cutting clearances increase the tendency for die galling and chipping. The severity of galling depends on the surface finish and microstructure of both the tool steel and work material. Chipping can occur when process stresses are high enough to cause low-cycle fatigue of the tooling material, indicating that the material lacks toughness.

Stamping Tool Failure Modes (Citations T-20 and U-7)

Tempering of tools and dies represents a critical heat-treatment step and serves more than one purpose, but of primary concern is the need to relieve residual stresses and impart toughness. Dies placed in service without proper tempering likely will experience early failure.

Dies made from the higher-alloy tool-steel grades (D, M or T grades) require more than one tempering step. These grades contain large amounts of retained austenite and untempered martensite after the first tempering step and require at least one more temper to relieve internal stresses, and sometimes a third temper for even greater toughness.

Unfortunately, heat treatment remains a “black-box” process for most die shops and manufacturing companies, which send soft die details to the local heat treat facility, with hardened details returned. A cursory Rockwell hardness test may be conducted at the die shop when the parts return. If they meet hardness requirements, the parts usually are accepted, regardless of how they may have been processed—a problem, as hardness alone does not adequately measure impact toughness.

Machines Get Stronger

The increased forces needed to form, cut and trim higher-strength steels create significant challenges for pressroom equipment and tooling. These include excessive tooling deflections, damaging tipping-moments, and amplified vibrations and snapthrough forces that can shock and break dies—and sometimes presses. Stamping AHSS materials can affect the size, strength, power and overall configuration of every major piece of the press line, including material-handling equipment, coil straighteners, feed systems and presses.

Here is what every stamper should know about higher-strength materials:

- Because higher-strength steels require more stress to deform, additional servo motor power and torque capability may be needed to pull the coil material through the straightener. Additional back tension between the coil feed and straightening equipment also may be required due to the higher yield strength of the material in the loop as the material tries to push back against the straightener and feed system.

- Higher-strength materials, due to their greater yield strengths, have a greater tendency to retain coil set. This requires greater horsepower to straighten the material to an acceptable level of flatness. Straightening higher-strength coils requires larger-diameter rolls and wider roll spacing in order to work the stronger material more effectively. But increasing roll diameter and center distances on straighteners to accommodate higher-strength steels limits the range of materials that can effectively be straightened. A straightener capable of processing 600-mm-wide coils to 10 mm thick in mild steel may still straighten 1.5-mm-thick material successfully. But a straightener sized to run the same width and thickness of DP steel might only be capable of straightening 2.5 mm or 3.0-mm thick mild steel. This limitation is primarily due to the larger rolls and broadly spaced centers necessary to run AHSS materials. The larger rolls, journals and broader center distances safeguard the straightener from potential damage caused by the higher stresses.

- Because higher-strength materials require greater stress to blank and punch as compared to HSLA or mild steel, they generate proportionally increased snapthrough and reverse-unloading forces. High-tensile snapthrough forces introduce large downward accelerations to the upper die half. These forces work to separate the upper die from the bottom of the ram on every stroke. Insufficient die-clamping force could cause the upper-die half to separate from the bottom of the ram on each stroke, causing fatigue to the upper-die mounting fasteners.

- Because energy is expended with each stroke of the press—and this energy must be replaced—critical attention must focus on the size (horsepower) of the main drive motor and the rotational speed of the flywheel in higher-strength-steel applications. The main motor, with its electrical connection, provides the only source of energy for the press and it must generate sufficient power to meet the demands of the stamping operation. The motor must be properly sized to replace the increased energy expended during each press stroke. For these reasons, some stampers consider the benefits of servo-driven presses for these applications.

As steels becomes stronger, a corresponding increase in process knowledge is required in terms of die design, construction and maintenance, and equipment selection.

You can read more about these topics at these links:

Tooling and Die Wear

Coil Processing Straightening and Leveling

Press Requirements

Thanks go to Peter Ulintz, of the Precision Metalforming Association (PMA) for authoring this article. Ulintz was employed in the metal stamping and tool & die industries for 38 years before joining Precision Metalforming Association (PMA) in 2015. He provides industry-related training and seminars in Stamping Press Operation and Setup; Designing and Building Metal Stamping Dies; Die Maintenance and Troubleshooting; Metal Stamping Design for Manufacturability; Deep Draw Tooling and Process Technology; Stamping Higher Strength Steels; and Problem Solving in the Press Shop. Peter is a contributor to ASM Handbook, Volume 14B, Metalworking: Sheet Forming (2006) and writes the monthly column, Tooling by Design, for PMA’s monthly publication, MetalForming Magazine.