Blog, homepage-featured-top, main-blog

Equipment, Responsibilities, and Property Development Considerations When Deciding How A Part Gets Formed

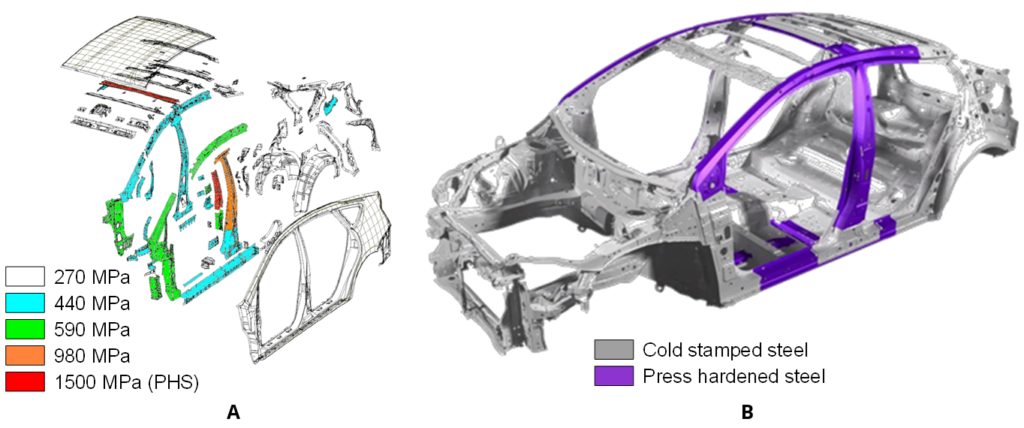

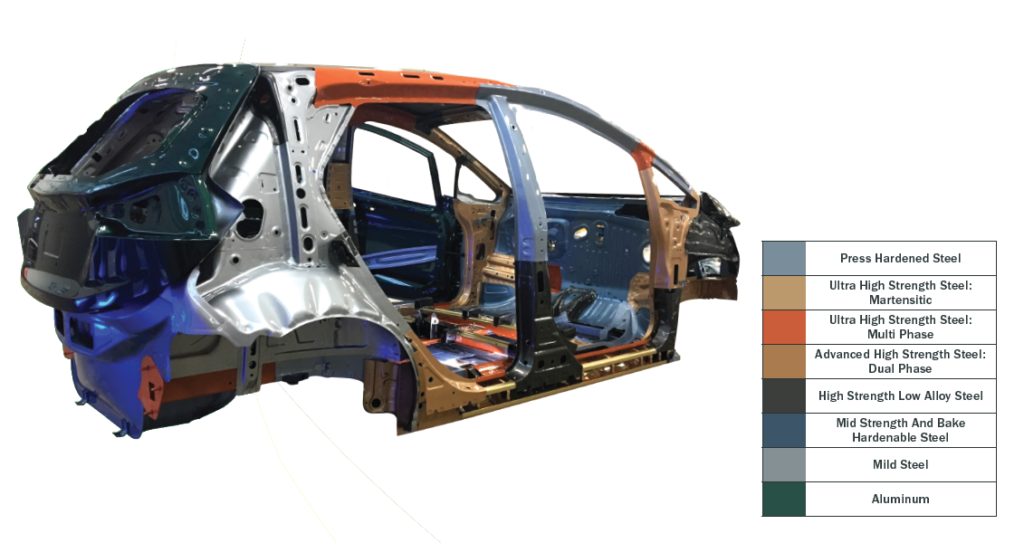

Automakers contemplating whether a part is cold stamped or hot formed must consider numerous ramifications impacting multiple departments. Over a series of blogs, we’ll cover some of the considerations that must enter the discussion.

The discussions relative to cold stamping are applicable to any forming operation occurring at room temperature such as roll forming, hydroforming, or conventional stamping. Similarly, hot stamping refers to any set of operations using Press Hardening Steels (or Press Quenched Steels), including those that are roll formed or fluid-formed.

Equipment

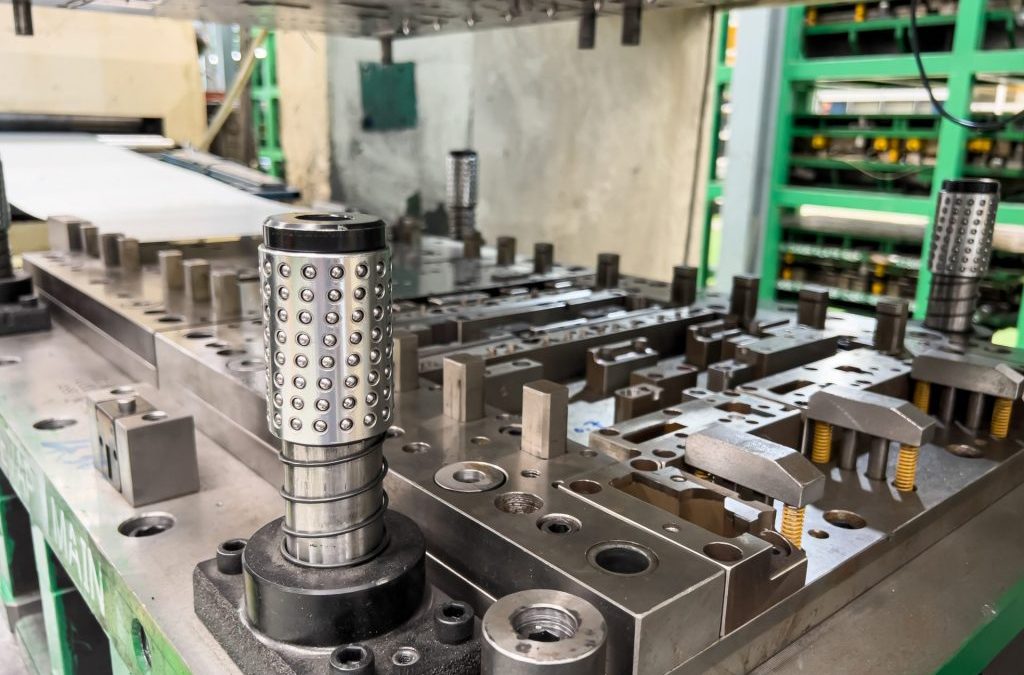

There is a well-established infrastructure for cold stamping. New grades benefit from servo presses, especially for those grades where press force and press energy must be considered. Larger press beds may be necessary to accommodate larger parts. As long as these factors are considered, the existing infrastructure is likely sufficient.

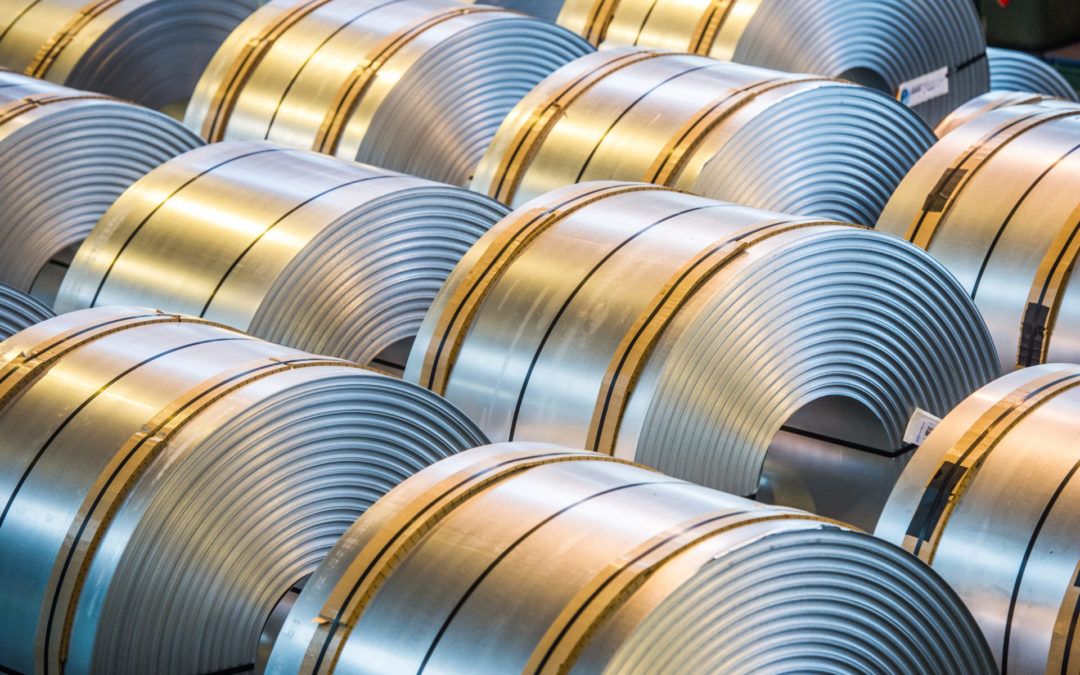

Progressive-die presses have tonnage ratings commonly in the range of 630 to 1250 tons at relatively high stroke rates. Transfer presses, typically ranging from 800 to 2500 tons, operate at relatively lower stroke rates. Power requirements can vary between 75 kW (630 tons) to 350 kW (2500 tons). Recent transfer press installations of approximately 3000 tons capacity allow for processing of an expanded range of higher strength steels.

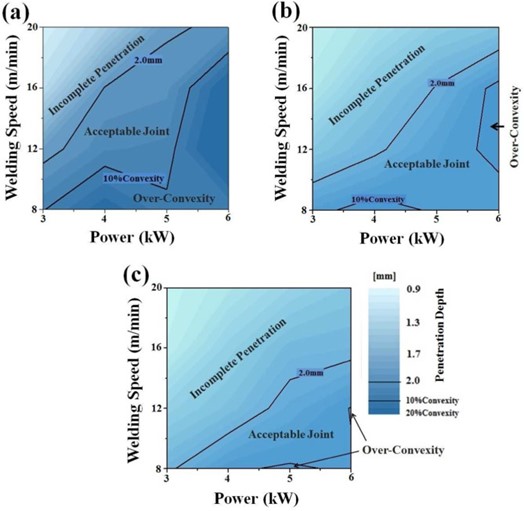

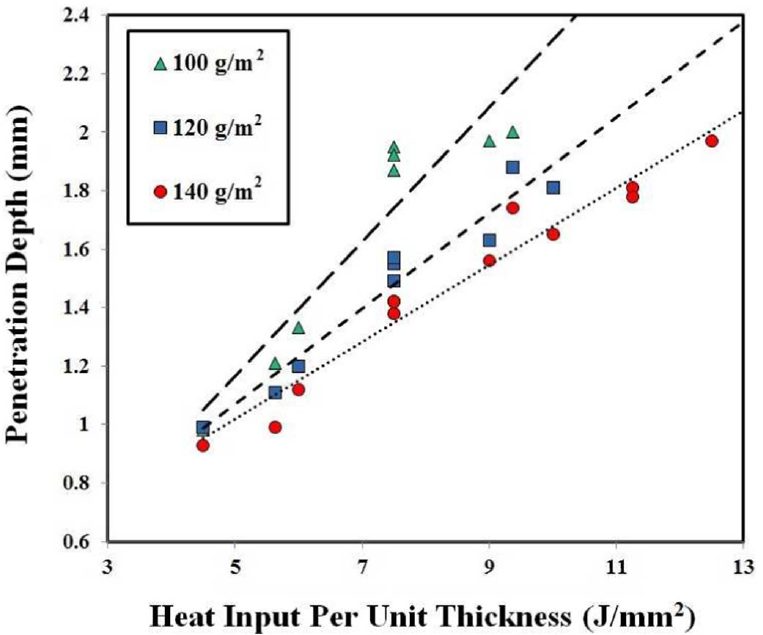

Hot stamping requires a high-tonnage servo-driven press (approximately 1000 ton force capacity) with a 3 meter by 2 meter bolster, fed by either a roller-hearth furnace more than 30 m long or a multi-chamber furnace. Press hardened steels need to be heated to 900 °C for full austenitization in order to achieve a uniform consistent phase, and this contributes to energy requirements often exceeding 2 MW.

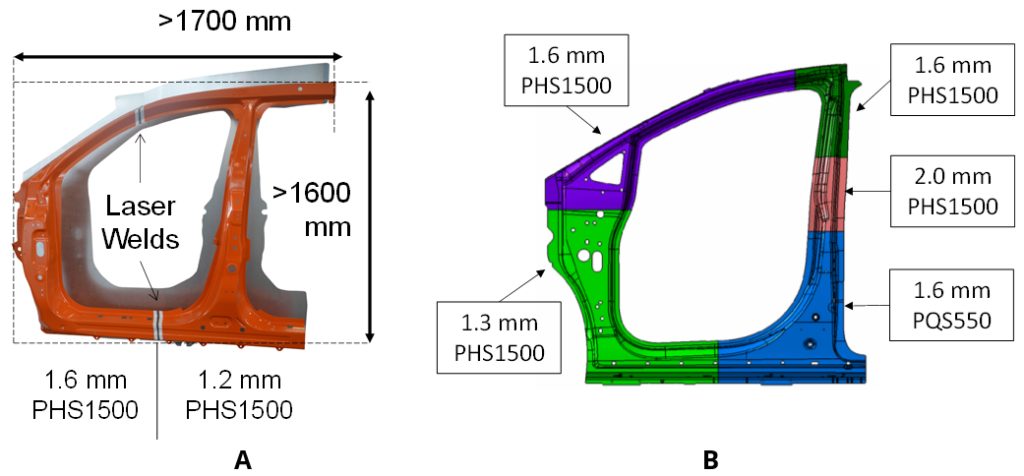

Integrating multiple functions into fewer parts leads to part consolidation. Accommodating large laser-welded parts such as combined front and rear door rings expands the need for even wider furnaces, higher-tonnage presses, and larger bolster dimensions.

Blanking of coils used in the PHS process occurs before the hardening step, so forces are low. Post-hardening trimming usually requires laser cutting, or possibly mechanical cutting if some processing was done to soften the areas of interest.

That contrasts with the blanking and trimming of high strength cold-forming grades. Except for the highest strength cold forming grades, both blanking and trimming tonnage requirements are sufficiently low that conventional mechanical cutting is used on the vast majority of parts. Cut edge quality and uniformity greatly impact the edge stretchability that may lead to unexpected fracture.

Responsibilities

Most cold stamped parts going into a given body-in-white are formed by a tier supplier. In contrast, some automakers create the vast majority of their hot stamped parts in-house, while others rely on their tier suppliers to provide hot stamped components. The number of qualified suppliers capable of producing hot stamped parts is markedly smaller than the number of cold stamping part suppliers.

Hot stamping is more complex than just adding heat to a cold stamping process. Suppliers of cold stamped parts are responsible for forming a dimensionally accurate part, assuming the steel supplier provides sheet metal with the required tensile properties achieved with a targeted microstructure.

Suppliers of hot stamped parts are also responsible for producing a dimensionally accurate part, but have additional responsibility for developing the microstructure and tensile properties of that part from a general steel chemistry typically described as 22MnB5.

Property Development

Independent of which company creates the hot formed part, appropriate quality assurance practices must be in place. With cold stamped parts, steel is produced to meet the minimum requirements for that grade, so routine property testing of the formed part is usually not performed. This is in contrast to hot stamped parts, where the local quench rate has a direct effect on tensile properties after forming. If any portion of the part is not quenched faster than the critical cooling rate, the targeted mechanical properties will not be met and part performance can be compromised. Many companies have a standard practice of testing multiple areas on samples pulled every run. It’s critical that these tested areas are representative of the entire part. For example, on the top of a hat-section profile where there is good contact between the punch and cavity, heat extraction is likely uniform and consistent. However, on the vertical sidewalls, getting sufficient contact between the sheet metal and the tooling is more challenging. As a result, the reduced heat extraction may limit the strengthening effect due to an insufficient quench rate.

For more information, see our Press Hardened Steel Primer to learn more about PHS grades and processing!

Thanks are given to Eren Billur, Ph.D., Billur MetalForm for his contributions to the Equipment section, as well as many of the webpages relating to Press Hardening Steels at www.AHSSinsights.org.

Danny Schaeffler is the Metallurgy and Forming Technical Editor of the AHSS Applications Guidelines available from WorldAutoSteel. He is founder and President of Engineering Quality Solutions (EQS). Danny wrote the monthly “Science of Forming” and “Metal Matters” column for Metalforming Magazine, and provides seminars on sheet metal formability for Auto/Steel Partnership and the Precision Metalforming Association. He has written for Stamping Journal and The Fabricator, and has lectured at FabTech. Danny is passionate about training new and experienced employees at manufacturing companies about how sheet metal properties impact their forming success.

![Press Hardened Steels]()

1stGen AHSS, AHSS, Press Hardened Steels, Steel Grades

Introduction

Press hardening steels are typically carbon-manganese-boron alloyed steels. They are also commonly known as:

- Press Hardening Steels (PHS)

- Hot Press Forming Steels (HPF), a term more common in Asia

- Boron Steel: although the name may also refer to other steels, in automotive industry boron steel is typically used for PHS

- Hot Formed Steel (HF), a term more common in Europe.

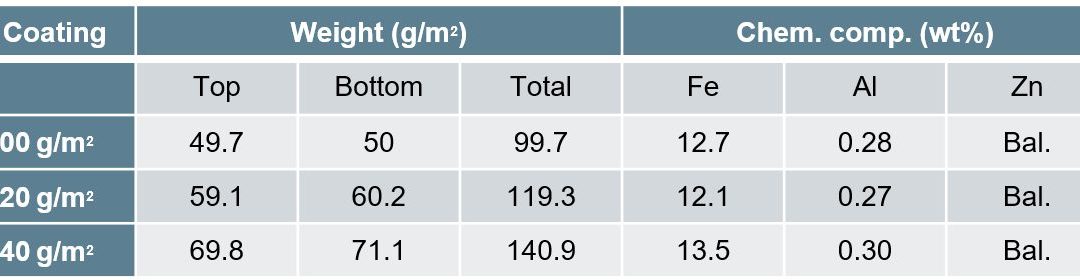

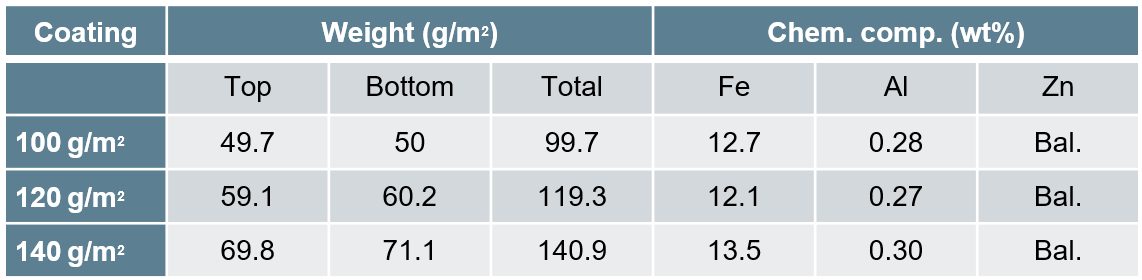

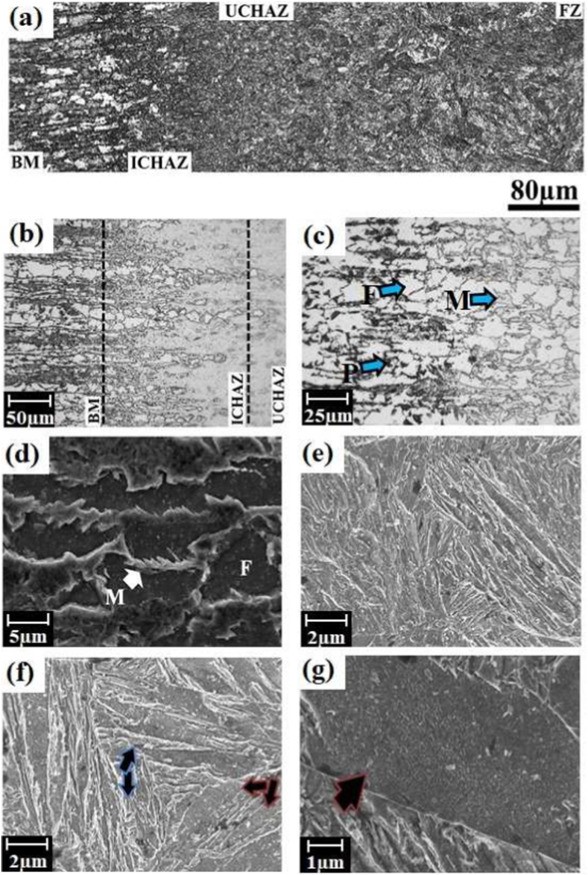

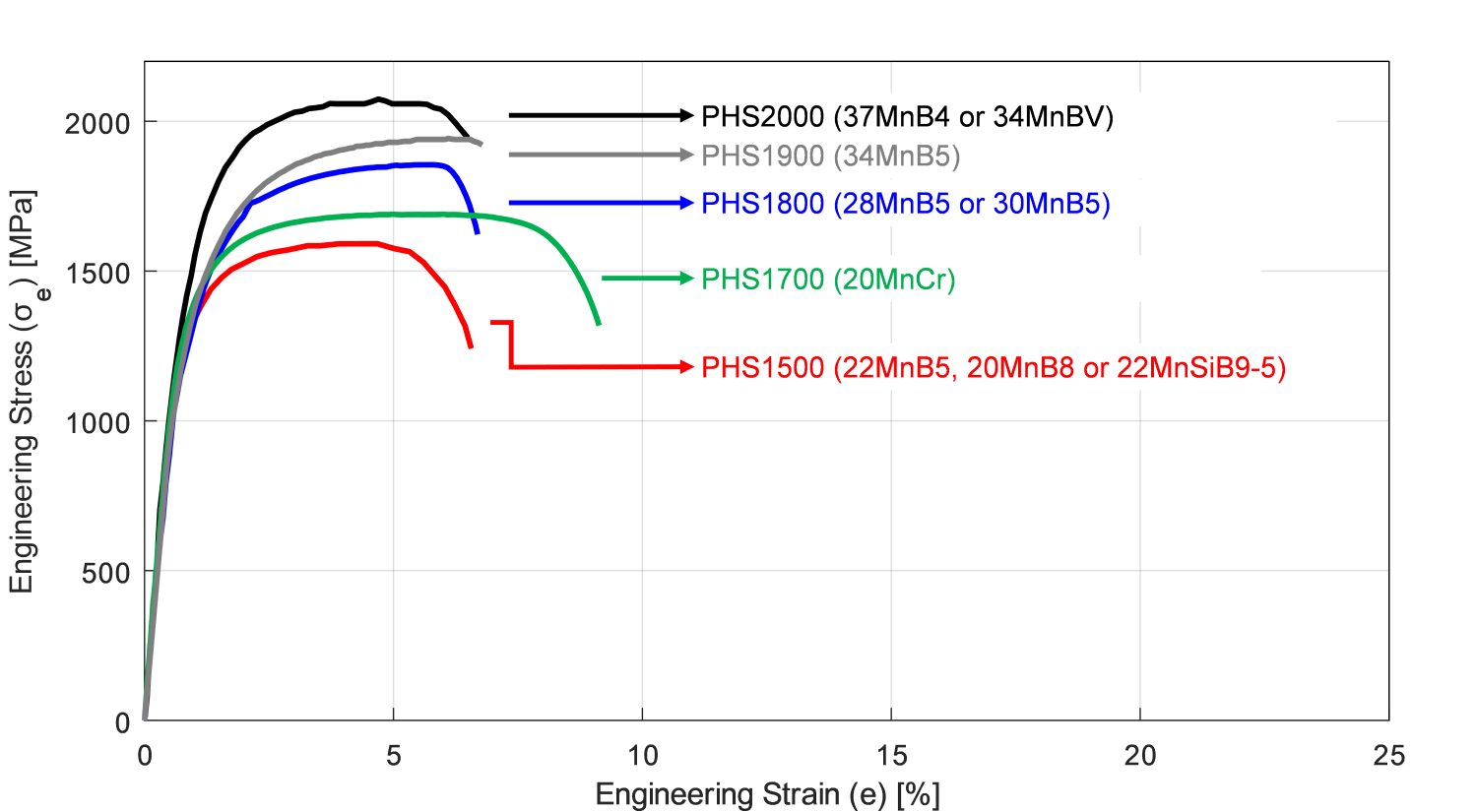

The most common PHS grade is PHS1500. In Europe, this grade is commonly referred to as 22MnB5 or 1.5528. As received, it has ferritic-pearlitic microstructure and a yield strength between 300-600 MPa depending on the cold working. The tensile strength of as received steel can be expected to be between 450 and 750 MPa. Total elongation must be over a minimum of 12% (A80), but depending on coating type and thickness may well exceed 18% (A80), see Figure 1*. Thus, the grade can be cold formed to relatively complex geometries using certain methods and coatings. When hardened, it has a minimum yield strength of 950 MPa and tensile strength typically around 1300-1650 MPa, Figure 1.B-14 Some companies describe them with their yield and tensile strength levels, such as PHS950Y1500T. It is also common in Europe to see this steel as PHS950Y1300T, and thus aiming for a minimum tensile strength of 1300 MPa after quenching.

The PHS1500 name may also be used for the Zn-coated 20MnB8 or air hardenable 22MnSiB9-5 grades. The former is known as “direct forming with pre-cooling steel” and could be abbreviated as CR1500T-PS, PHS1500PS, PHSPS950Y1300T or similar. The latter grade is known as “multi-step hot forming steel” and could be abbreviated as, CR1500T-MS, PHS1500MS, PHSMS950Y1300T or similar.V-9

Figure 1: Stress-Strain Curves of PHS1500 before and after quenching* (re-created after Citations U-9, O-8, B-18).

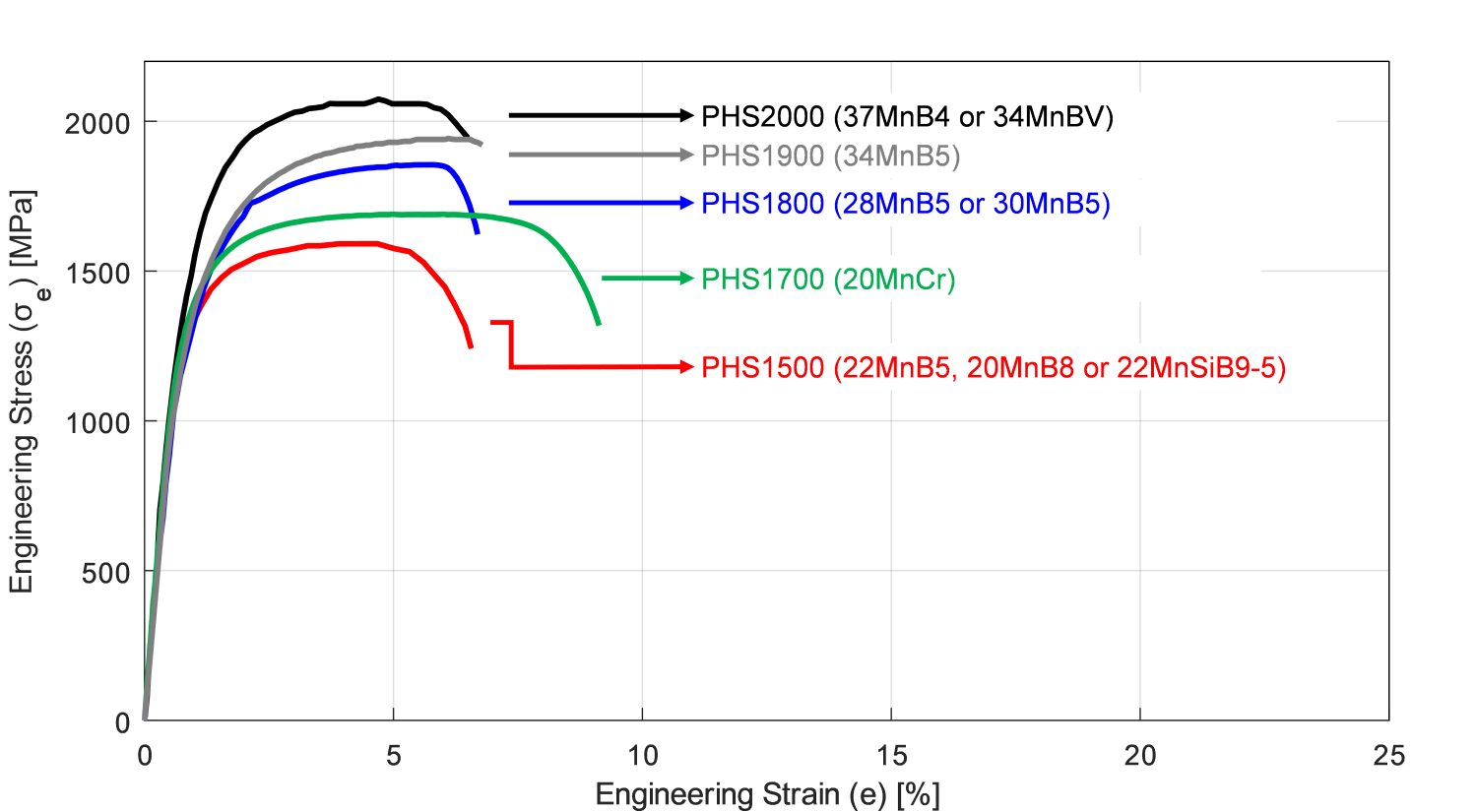

In the last decade, several steel makers introduced grades with higher carbon levels, leading to a tensile strength between 1800 MPa and 2000 MPa. Hydrogen induced cracking (HIC) and weldability limit applications of PHS1800, PHS1900 and PHS2000, with studies underway to develop practices which minimize or eliminate these limitations.

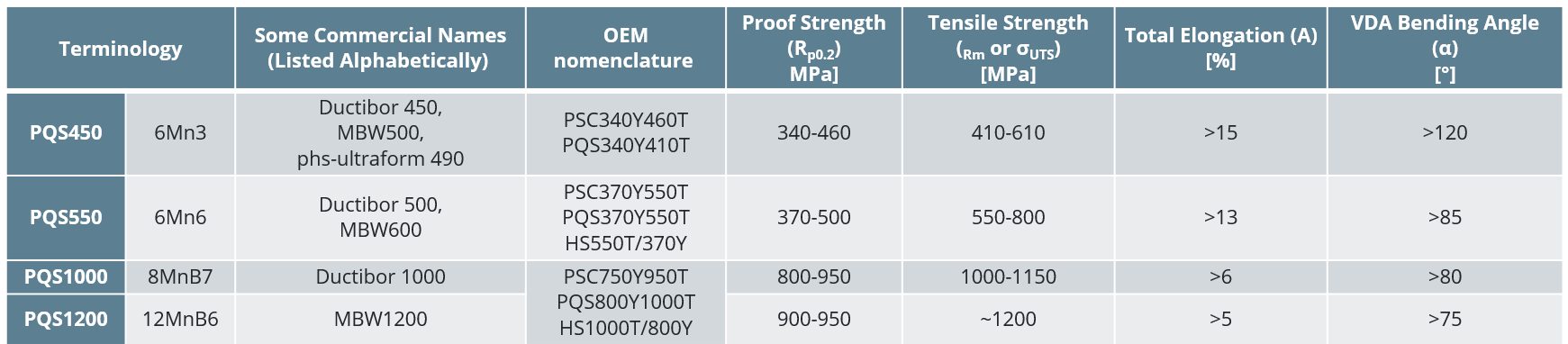

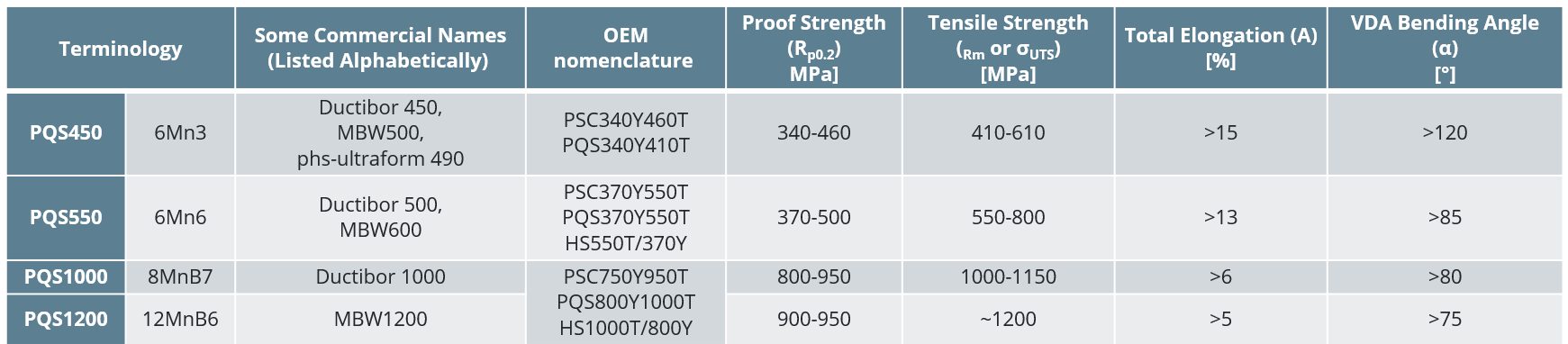

Lastly, there are higher energy absorbing, lower strength grades, which have improved ductility and bendability. These fall into two main groups: Press Quenched Steels (PQS) with approximate tensile strength levels of 450 MPa and 550 MPa (noted as PQS450 and PQS550 in Figure 2) and higher ductility PHS grades with approximate tensile strength levels of 1000 and 1200 MPa (shown as PHS1000 and PHS1200 in Figure 2).

Apart from these grades, other grades are suitable for press hardening. Several research groups and steel makers have offered special stainless-steel grades and recently developed Medium-Mn steels for hot stamping purposes. Also, one steel maker in Europe has developed a sandwich material by cladding PHS1500 with thin PQS450 layers on both sides.

Figure 2: Stress-strain curves of several PQS and PHS grades used in automotive industry, after hot stamping for full hardening* (re-created after Citations B-18, L-28, Z-7, Y-12, W-28, F-19, G-30).

PHS Grades with Tensile Strength Approximately 1500 MPa

Hot stamping as we know it today was developed in 1970s in Sweden. The most used steel since then has been 22MnB5 with slight modifications. 22MnB5 means, approximately 0.22 wt-% C, approximately (5/4) = 1.25% wt-% Mn, and B alloying.

The automotive use of this steel started in 1984 with door beams. Until 2001, the automotive use of hot stamped components was limited to door and bumper beams, made from uncoated 22MnB5, in the fully hardened condition. By the end of the 1990s, Type 1 aluminized coating was developed to address scale formation. Since then, 22MnB5 + AlSi coating has been used extensively.B-14

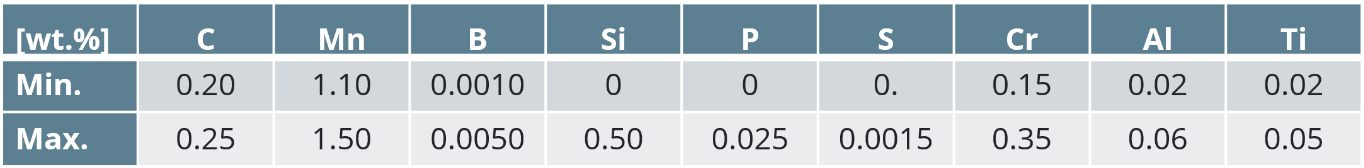

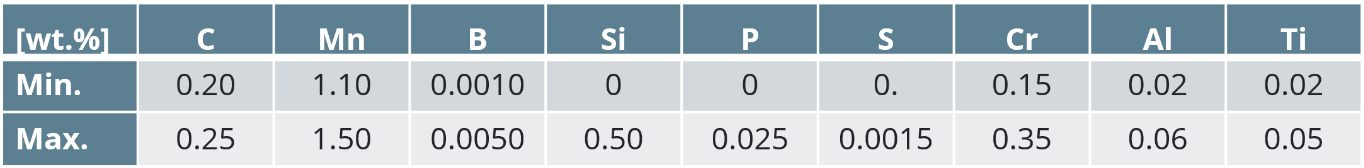

Although some steel makers claim 22MnB5 as a standard material, it is not listed in any international or regional (i.e., European, Asian, or American) standard. Only a similar 20MnB5 is listed in EN 10083-3.T-26, E-3 The acceptable range of chemical composition for 22MnB5 is given in Table 1.S-64, V-9

Table 1: Chemical composition limits for 22MnB5 (listed in wt.%).S-64, V-9

VDA239-500, a draft material recommendation from Verband Der Automotbilindustrie E.V. (VDA), is an attempt to further standardize hot stamping materials. The document has not been published as of early 2021. According to this draft standard, 22MnB5 may be delivered coated or uncoated, hot or cold rolled. Depending on these parameters, as-delivered mechanical properties may differ significantly. Steels for the indirect process, for example, has to have a higher elongation to ensure cold formability.V-9 Figure 1 shows generic stress-strain curves, which may vary significantly depending on the coating and selected press hardening process.

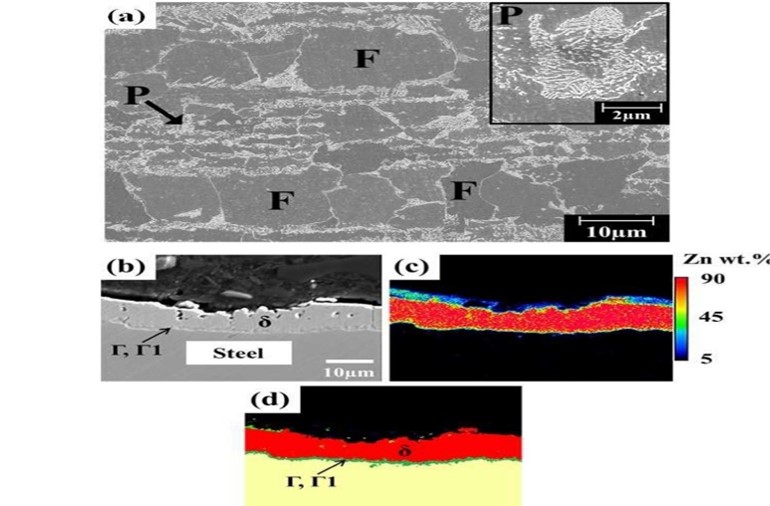

For 22MnB5 to reach its high strength after quenching, it must be austenitized first. During heating, ferrite begins to transform to austenite at “lower transformation temperature” known as Ac1. The temperature at which the ferrite-to-austenite transformation is complete is called “upper transformation temperature,” abbreviated as Ac3. Both Ac1 and Ac3 are dependent on the heating rate and the exact chemical composition of the alloy in question. The upper transformation temperature for 22MnB5 is approximately 835-890 °C.D-21, H-30Austenite transforms to other microstructures as the steel is cooled. The microstructures produced from this transformation depends on the cooling rate, as seen in the continuous-cooling-transformation (CCT) curve in Figure 3. Achieving the “fully hardened” condition in PHS grades requires an almost fully martensitic microstructure. Avoiding transformation to other phases requires cooling rates exceeding a minimum threshold, called the “critical cooling rate,” which for 22MnB5 is 27 °C/s. For energy absorbing applications, there are also tailored parts with “soft zones”. In these soft zones, areas of interest will be intentionally made with other microstructures to ensure higher energy absorption.B-14

Figure 3: Continuous Cooling Transformation (CCT) curve for 22MnB5 (Published in Citation B-19, re-created after Citations M-25, V-10).

Once the parts are hot stamped and quenched over the critical cooling rate, they typically have a yield strength of 950-1200 MPa and an ultimate tensile strength between 1300 and 1700 MPa. Their hardness level is typically between 470 and 510 HV, depending on the testing methods.B-14

Once automotive parts are stamped, they are then joined to the car body in body shop. The fully assembled body known as the Body-in-White (BIW) with doors and closures, is then moved to the paint shop. Once the car is coated and painted, the BIW passes through a furnace to cure the paint. The time and temperature for this operation is called the paint bake cycle. Although the temperature and duration may be different from plant to plant, it is typically close to 170 °C for 20 minutes. Most automotive body components made from cold or hot formed steels and some aluminum grades may experience an increase in their yield strength after paint baking.

In Figure 4, press hardened 22MnB5 is shown in the red curve. In this particular example, the proof strength was found to be approximately 1180 MPa. After processing through the standard 170 °C – 20 minutes bake hardening cycle, the proof strength increases to 1280 MPa (shown in the black curve).B-18 Most studies show a bake hardening increase of 100 MPa or more with press hardened 22MnB5 in industrial conditions.B-18, J-17, C-17

Figure 4: Bake hardening effect on press hardened 22MnB5. BH0 is shown since there is no cold deformation pre-strain. (re-created after Citation B-18).

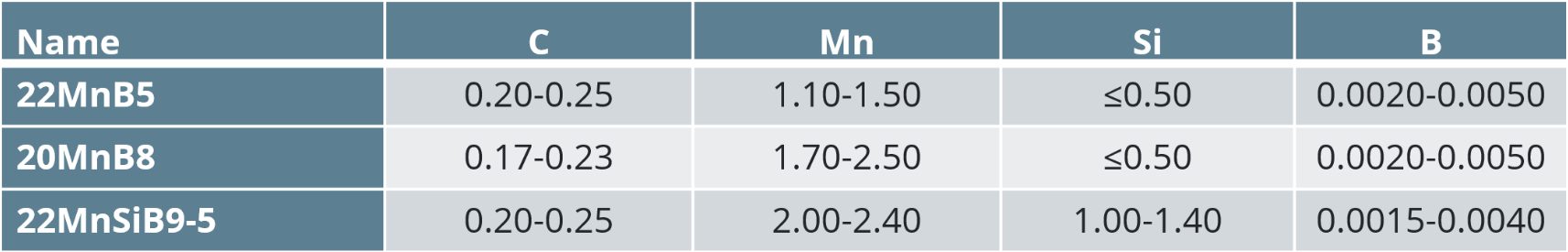

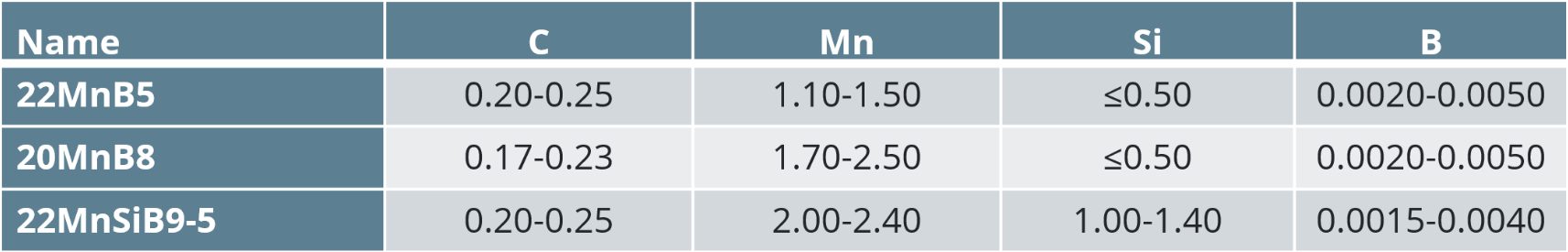

There are two modified versions of the 22MnB5 recently offered by several steel makers: 20MnB8 and 22MnSiB9-5. Both grades have higher Mn and Si compared to 22MnB5, as shown in Table 2.

Table 2: Chemical compositions of PHS grades with 1500 MPa tensile strength (all listed in wt.%).V-9

Both of these relatively recent grades are designed for Zn-based coatings and are designed for different process routes. For these reasons, many existing hot stamping lines would require some modifications to accommodate these grades.

20MnB8 has been designed for a “direct process with pre-cooling”. The main idea is to solidify the Zn coating before forming, eliminating the possibility that liquid zine fills in the micro-cracks on the formed base metal surface, which in turn eliminates the risk of Liquid Metal Embrittlement (LME). The chemistry is modified such that the phase transformations occur later than 22MnB5. The critical cooling rate of 20MnB8 is approximately 10 °C/s. This allows the part to be transferred from the pre-cooling stage to the forming die. As press hardened, the material has approximately 1000-1050 MPa yield strength and 1500 MPa tensile strength. Once bake hardened (170 °C, 20 minutes), yield strength may exceed 1100 MPa.K-22 This steel may be referred to as PHS950Y1300T-PS (Press Hardening Steel with minimum 950 MPa yield, minimum 1300 MPa tensile strength, for Pre-cooled Stamping).

22MnSiB9-5 has been developed for a transfer press process, named as “multi-step”. As quenched, the material has similar mechanical properties with 22MnB5 (Figure 5). As of 2020, there is at least one automotive part mass produced with this technology and is applied to a compact car in Germany.G-27 Although the critical cooling rate is listed as 5 °C/s, even at a cooling rate of 1 °C/s, hardness over 450HV can be achieved, as shown in Figure 6.H-27 This allows the material to be “air-hardenable” and thus, can handle a transfer press operation (hence the name multi-step) in a servo press. This material is also available with Zn coating.B-15 This steel may be referred to as PHS950Y1300T-MS (Press Hardening Steel with minimum 950 MPa yield, minimum 1300 MPa tensile strength, for Multi-Step process).

Figure 5: Engineering stress-strain curves of 1500 MPa level grades (re-created after Citations B-18, G-29, K-22)

Figure 6: Critical cooling rates of 1500 MPa level press hardening steels (re-created after Citations K-22, H-31, H-27)

Grades with Higher Ductility

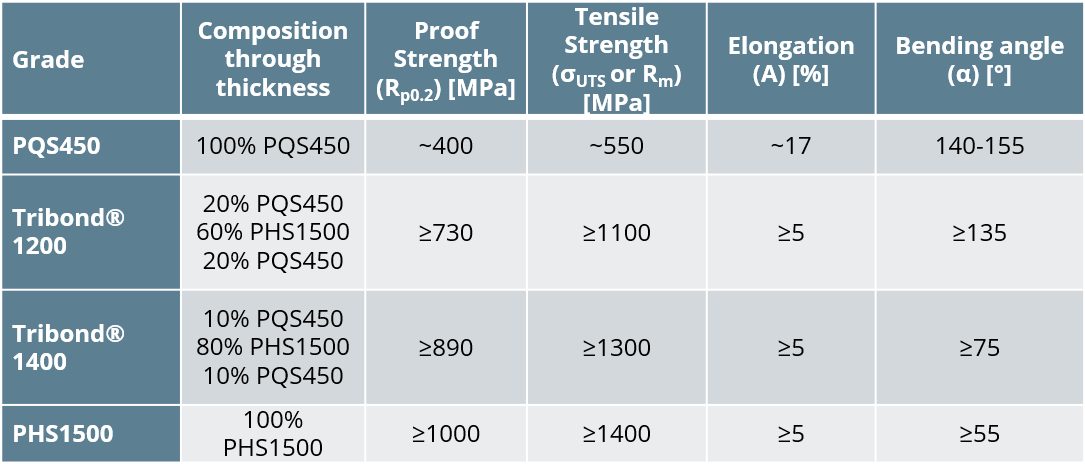

Press hardened parts are extremely strong, but cannot absorb much energy. Thus, they are mostly used where intrusion resistance is required. However, newer materials for hot stamping have been developed which have higher elongation (ductility) compared to the most common 22MnB5. These materials can be used in parts where energy absorption is required. These higher energy absorbing, lower strength grades fall into two groups, as shown in Figure 7. Those at the lower strength level are commonly referred to as “Press Quenched Steels” (PQS). The products having higher strength in Figure 7 are press hardening steels since they contain boron and do increase in strength from the quenching operation. The properties listed are after the hot stamping process.

- 450–600 MPa tensile strength level and >15% total elongation, listed as PQS450 and PQS550.

- 1000–1300 MPa tensile strength level and >5% total elongation, listed as PHS1000 and PHS1200.

Figure 7: Stress-strain curves of several PQS and PHS grades used in automotive industry, after hot stamping for full hardening* (re-created after Citations B-18, Y-12).

Currently none of these grades are standardized. Most steel producers have their own nomination and standard, as summarized in Table 3. There is a working document by German Association of Automotive Industry (Verband der Automobilindustrie, VDA), which only specifies one of the PQS grades. In the draft standard, VDA239-500, PQS450 is listed as CR500T-LA (Cold Rolled, 500 MPa Tensile strength, Low Alloyed). Similarly, PQS550 is listed as CR600T-LA.V-9 Some OEMs may prefer to name these grades with respect to their yield and tensile strength together, as listed in Table 3.

Table 3: Summary of Higher Ductility grades. The terminology descriptions are not standardized. Higher Ductility grade names are based on their properties and terminology is derived from a possible chemistry or OEM description. The properties listed here encompass those presented in multiple sources and may or may not be associated with any one specific commercial grade.Y-12, T-28, G-32

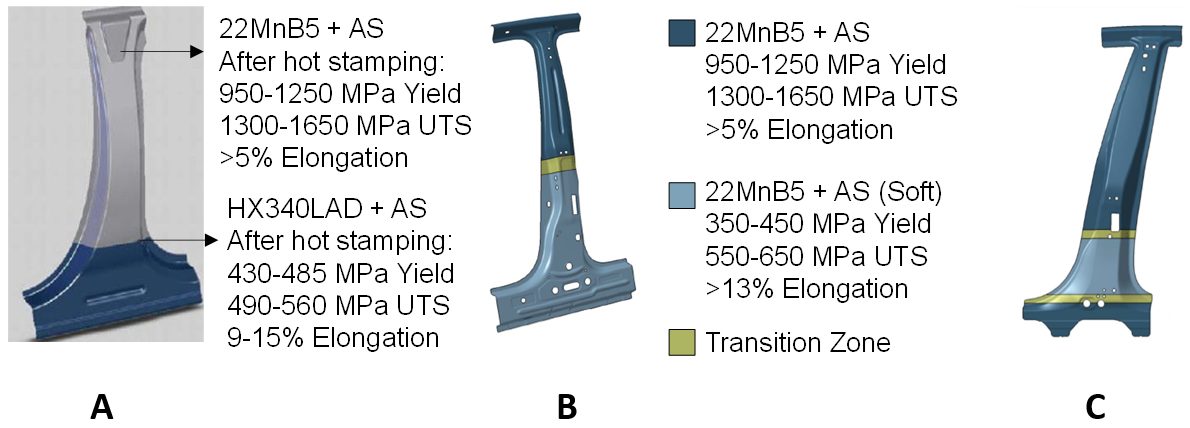

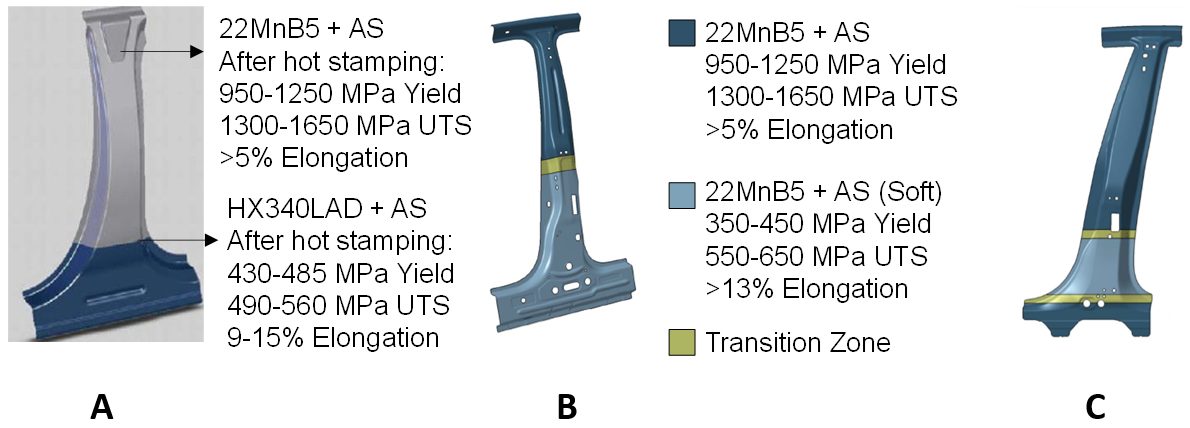

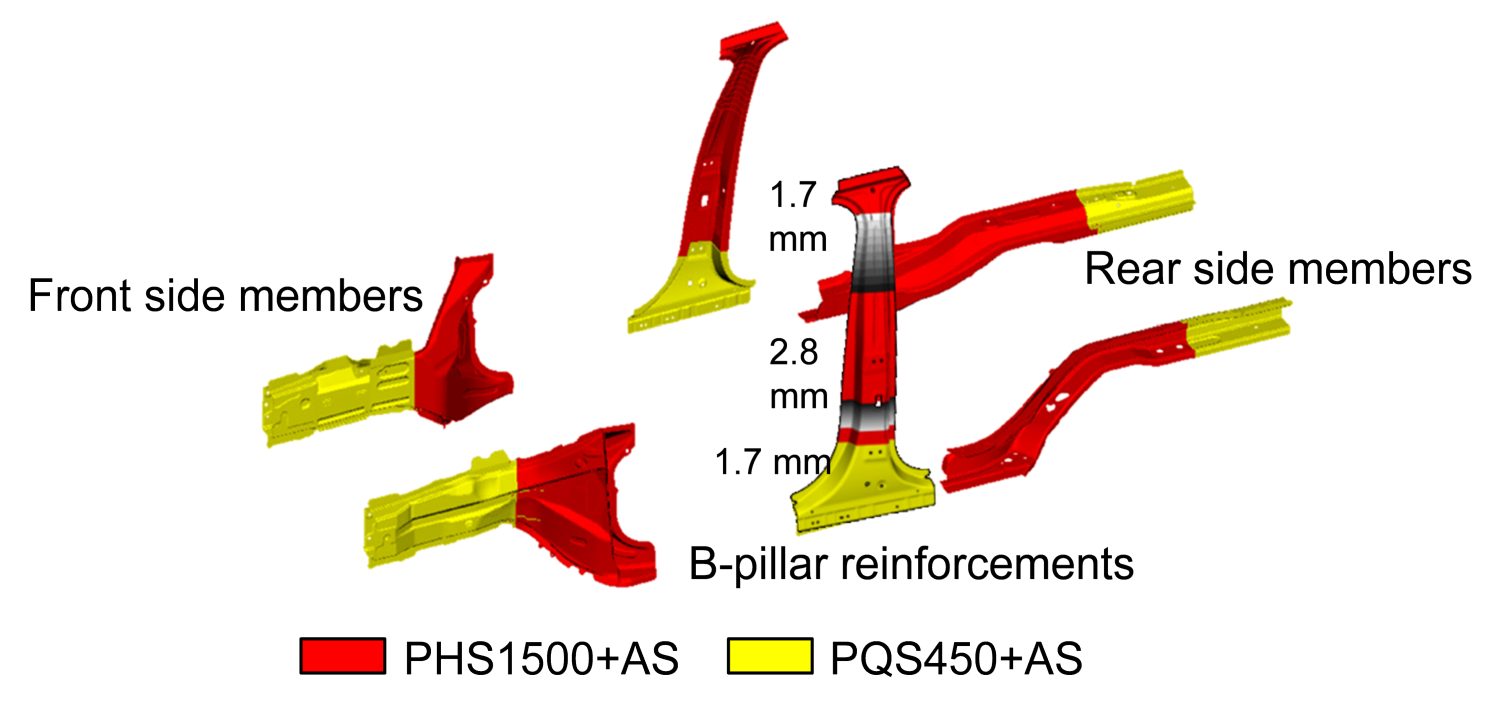

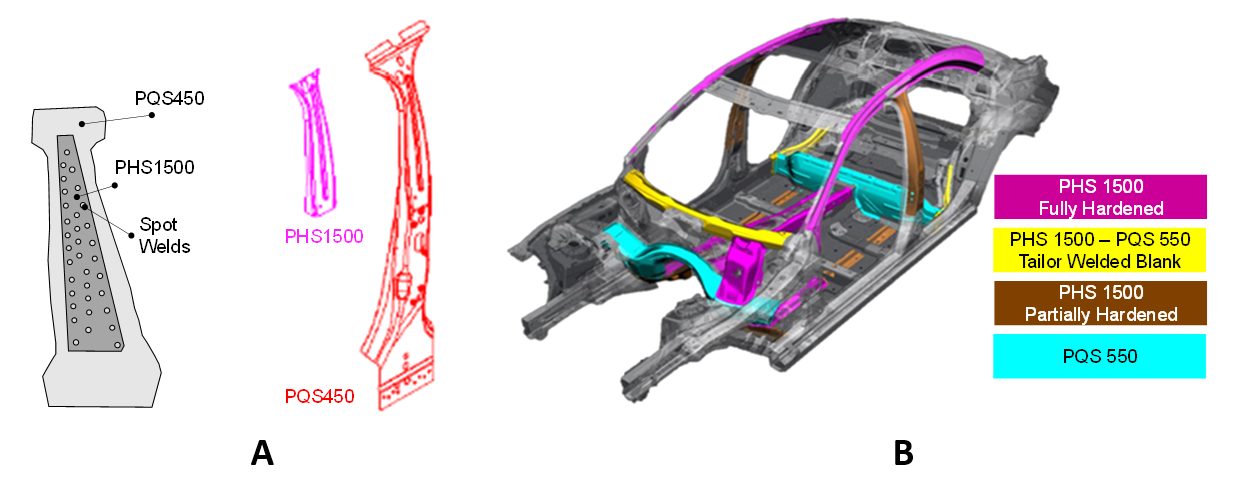

PQS grades have been under development at least since 2002. In the earliest studies, PQS 1200 was planned.R-11 Between 2007 and 2009, three new cars were introduced in Europe, having improved “energy absorbing” capacity in their hot stamped components. VW Tiguan (2007-2016) and Audi A5 Sportback (2009-2016) had soft zones in their B-pillars (Figure 8B and C). Intentionally reducing the cooling rate in these soft zone areas produces microstructures having higher elongations. In the Audi A4 (2008-2016) a total of three laser welded tailored blanks were hot stamped. The soft areas of the A4 B-pillars were made of HX340LAD+AS (HSLA steel, with AlSi coating, as delivered, min yield strength = 340 MPa, tensile strength = 410-510 MPa) as shown in Figure 8A. After the hot stamping process, HX340LAD likely had a tensile strength between 490 and 560 MPaS-65, H-32, B-20, D-22, putting it in the range of PQS450 (see Table 3). Note that there were not the only cars to have tailored hot stamped components during that time.

Figure 8: Earliest energy absorbing hot stamped B-pillars: (A) Audi A4 (2008-2016) had a laser welded tailored blank with HSLA material; (B) VW Tiguan (2007-2015) and (C) Audi A5 Sportback (2009-2016) had soft zones in their B-pillars (re-created after Citations H-32, B-20, D-22).

A 2012 studyK-25 showed that a laser welded tailored B-Pillar with 340 MPa yield strength HSLA and 22MnB5 had the best energy absorbing capacity in drop tower tests, compared to a tailored (part with a ductile soft-zone) or a monolithic part, Figure 9. As HSLA is not designed for hot stamping, most HSLA grades may have very high scatter in the final properties after hot stamping depending on the local cooling rate. Although the overall part may be cooled at an average 40 to 60 °C/s, at local spots the cooling rate may be over 80 °C/s. PQS grades are developed to have stable mechanical properties after a conventional hot stamping process, in which high local cooling rates may be possible.M-26, G-31, T-27

Figure 9: Energy absorbing capacity of B-pillars increase significantly with soft zones or laser welded tailored blank with ductile material (re-created after Citation K-25).

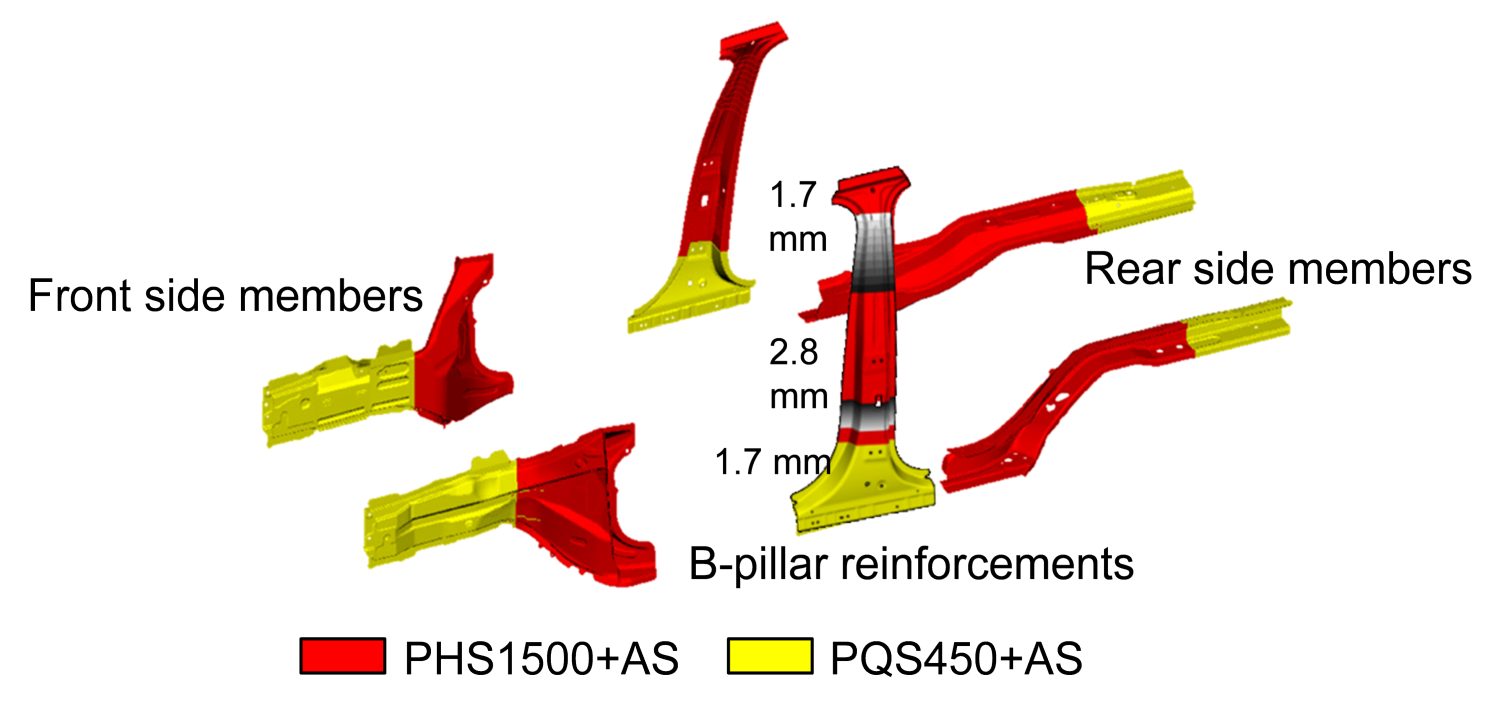

PQS grades have been in use at latest since 2014. One of the earliest cars to announce using PQS450 was VolvoXC90. There are six components (three right + three left), tailor welded blanks with PQS450, as shown Figure 10.L-29 Since then, many carmakers started to use PQS450 or PQS550 in their car bodies. These include:

- Fiat 500X: Patchwork supported, laser welded tailored rear side member with PQS450 in crush zonesD-23,

- Fiat Tipo (Hatchback and Station Wagon versions): similar rear side member with PQS450B-14,

- Renault Scenic 3: laser welded tailored B-pillar with PQS550 in the lower sectionF-19,

- Chrysler Pacifica: five-piece front door ring with PQS550 in the lower section of the B-Pillar areaT-29, and

- Chrysler Ram: six-piece front door ring with PQS550 in the lower section of the B-Pillar area.R-3

Figure 10: Use of laser welded tailored PQS-PHS grades in 2nd generation Volvo XC90 (re-created after Citation L-29).

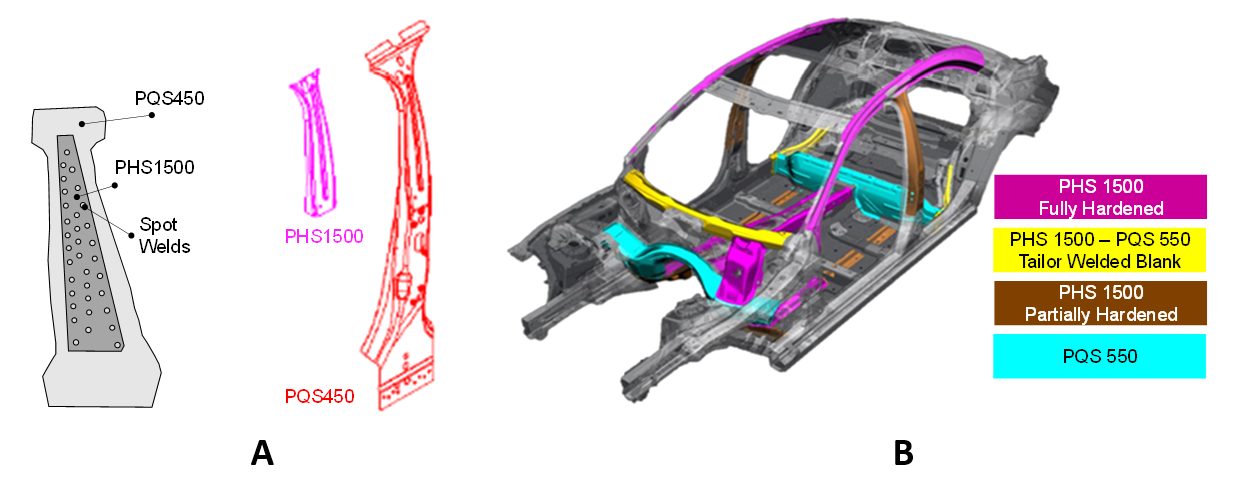

Several car makers use PQS grades to facilitate joining of components. The B-Pillar of the Jaguar I-PACE electric SUV is made of PQS450, with a PHS1500 patch that is spot welded before hot stamping, creating the patchwork blank shown in Figure 11A.B-21 Early PQS applications involved a laser welded tailored blank with PHS 1500. Since 2014, Mercedes hot stamped PQS550 blanks not combined with PHS1500. Figure 11B shows such components on the Mercedes C-Class.K-26

Figure 11: Recent PQS applications: (a) 2018 Jaguar I-PACE uses a patchwork B-pillar with PQS450 master blank and PHS1500 patchB-21, (b) 2014 Mercedes C-Class has a number of PQS550 components that are not laser welded to PHS1500.K-26

PHS Grades over 1500 MPa

The most commonly used press hardening steels have 1500 MPa tensile strength, but are not the only optionsR-11, with 4 levels between 1700 and 2000 MPa tensile strength available or in development as shown in Figure 12. Hydrogen induced cracking (HIC) and weldability problems limit widespread use in automotive applications, with studies underway to develop practices which minimize or eliminate these limitations.

Figure 12: PHS grades over 1500 MPa tensile strength, compared with the common PHS1500 (re-created after Citations B-18, W-28, Z-7, L-30, L-28, B-14).

Mazda Motor Corporation was the first vehicle manufacturer to use higher strength boron steels, with the 2011 CX-5 using 1,800MPa tensile strength reinforcements in front and rear bumpers, Figure 13. According to Mazda, the new material saved 4.8 kg per vehicle. The chemistry of the steel is Nb modified 30MnB5.H-33, M-28 Figure 14 shows the comparison of bumper beams with PHS1500 and PHS1800. With the higher strength material, it was possible to save 12.5% weight with equal performance.H-33

Figure 13: Bumper beam reinforcements of Mazda CX-5 (SOP 2011) are the first automotive applications of higher strength boron steels.M-28

Figure 14: Performance comparison of bumper beams with PHS1500 and PHS1800.H-33

PHS 1800 is used in the 2022 Genesis Electrified G80 (G80EV) and the new G90, both from Hyundai Motor. A specialized method lowering the heating furnace temperature by more than 50℃ limits the penetration of hydrogen into the blanks, minimizing the risk of hydrogen embrittlement. L-64.

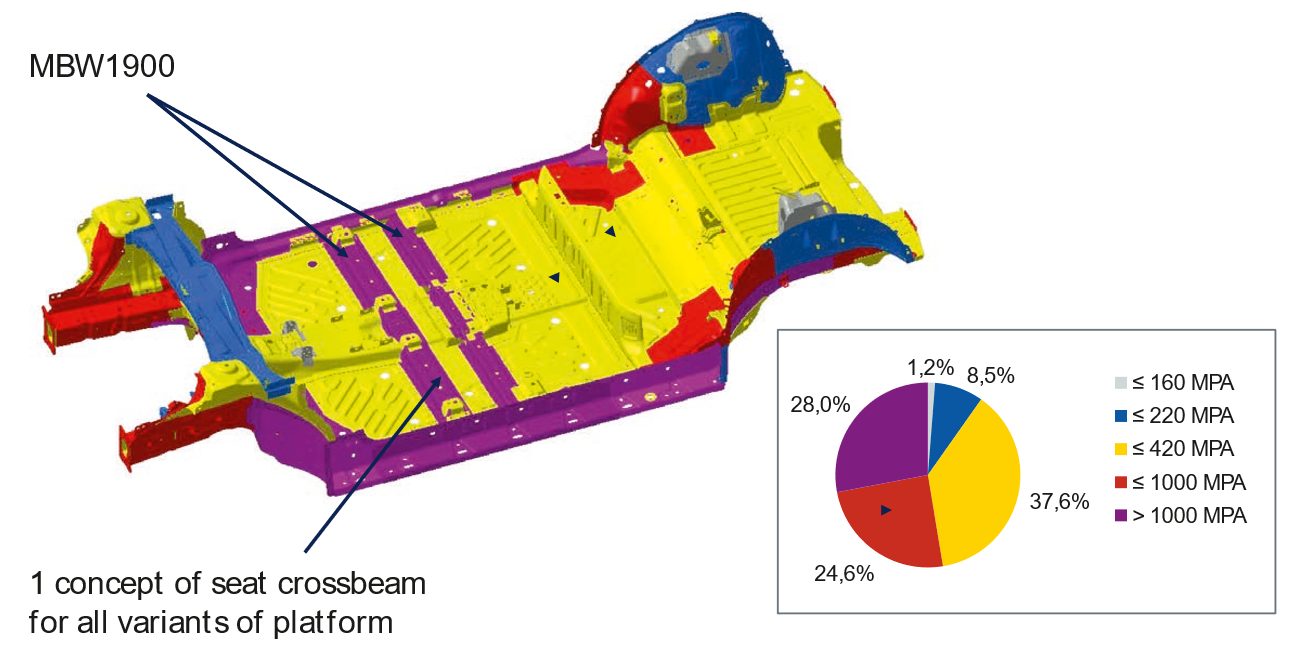

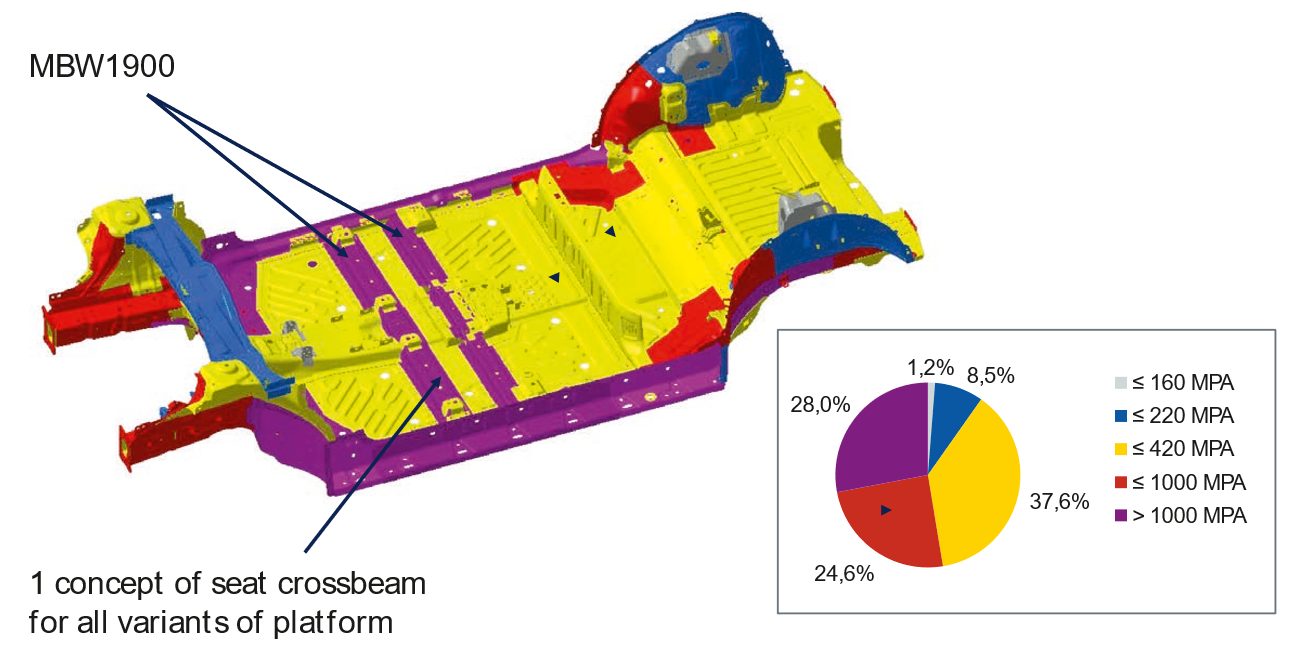

MBW 1900 is the commercial name for a press hardening steel with 1900 MPa tensile strength. An MBW 1900 B-pillar with correct properties can save 22% weight compared to DP 600 and yet may cost 9% less than the original Dual-Phase design.H-34 Ford had also demonstrated that by using MBW 1900 instead of PHS 1500, a further 15% weight could be saved.L-30 Since 2019, VW’s electric vehicle ID.3 has two seat crossbeams made of MBW 1900 steel, as seen in Figure 15.L-31 The components are part of MEB platform (Modularer E-Antriebs-Baukasten – modular electric-drive toolkit) and may be used in other VW Group EVs.

Figure 15: Underbody of VW ID3 (part of MEB platform).L-31

USIBOR 2000 is the commercial name given to a steel grade similar to 37MnB4 with an AlSi coating. Final properties are expected only after paint baking cycle, and the parts made with this grade may be brittle before paint bake.B-32 In June 2020, Chinese Great Wall Motors started using USIBOR 2000 in the Haval H6 SUV.V-12

HPF 2000, another commercial name, is used in a number of component-based examples, and also in the Renault EOLAB concept car.L-28, R-12 An 1800 MPa grade is under development.P-22 Docol PHS 1800, a commercial grade approximating 30MnB5, has been in production, with Docol PHS 2000 in development.S-66 PHS-Ultraform 2000, a commercial name for a Zn (GI) coated blank, is suited for the indirect process.V-11

General Motors China, together with several still mills across the country, have developed two new PHS grades: PHS 1700 (20MnCr) and PHS2000 (34MnBV). 20MnCr uses Cr alloying to improve hardenability and oxidation resistance. This grade can be hot formed without a coating. The furnace has to be conditioned with N2 gas. The final part has high corrosion resistance, approximately 9% total elongation (see Figure 12) and high bendability (see Table 4). 34MnBV on the other hand, has a thin AlSi coating (20g/m2 on each side). Compared with the typical thickness of AlSi coatings, thinner coatings are preferred for bendability (see Table 5).W-28 More information about these oxidation resistant PHS grades, as well as a 1200 MPa version intended for applications benefiting from enhanced crash energy absorption, can be found in Citation L-60.

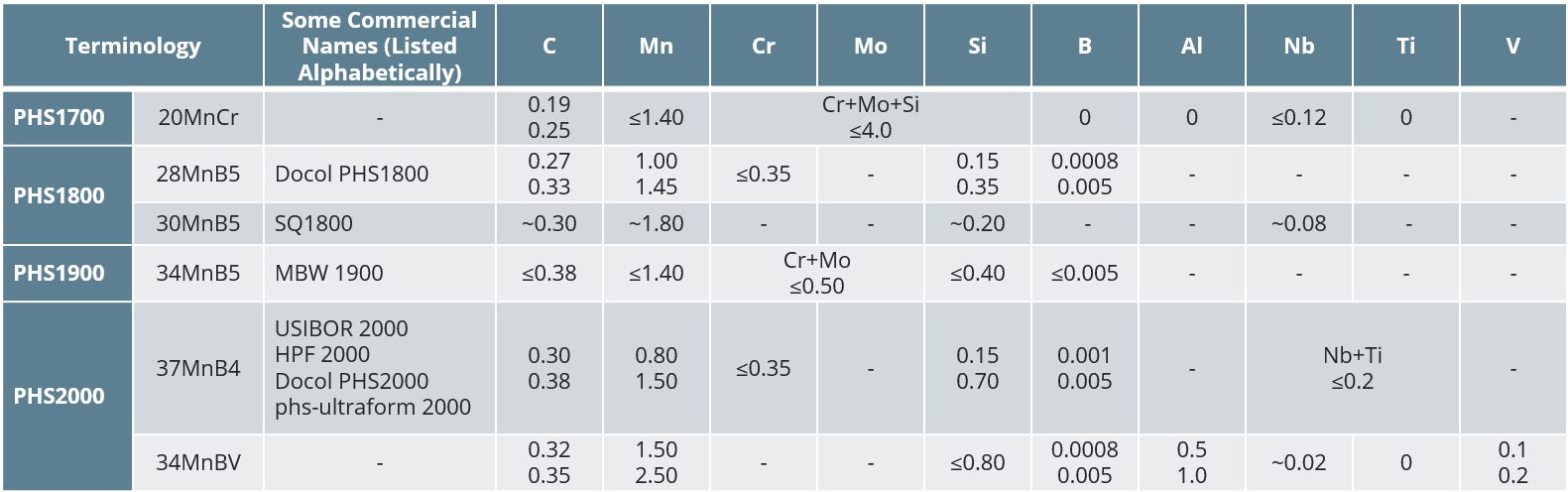

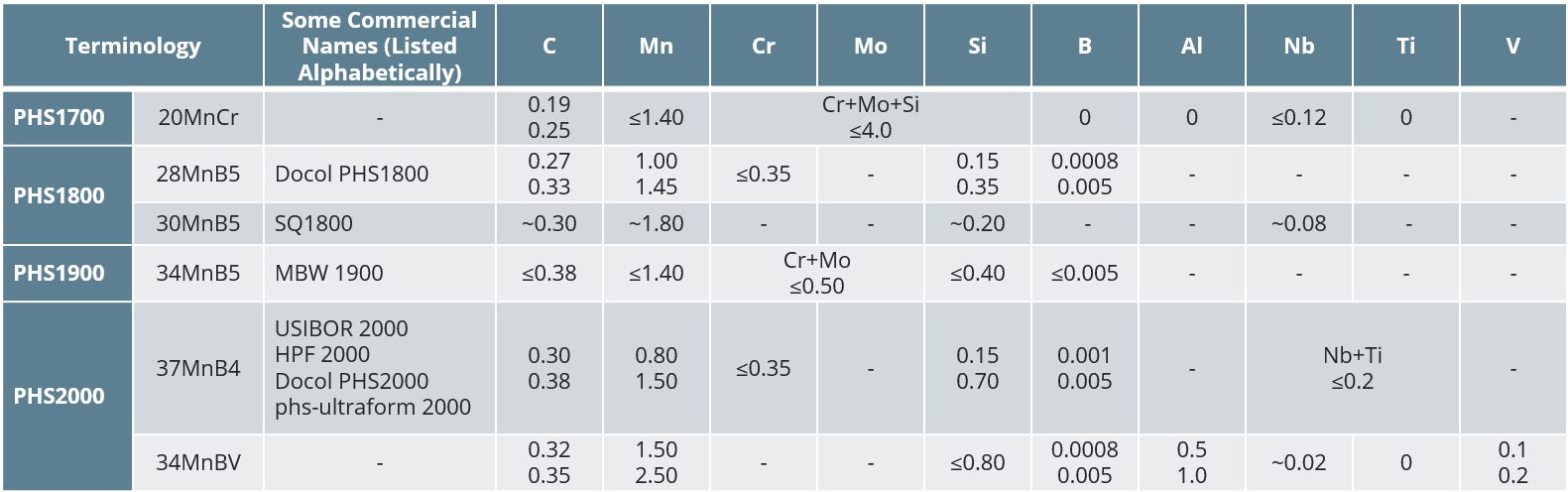

Table 4: Chemical compositions of higher strength PHS grades. “0” means it is known that there is no alloying element, while “-” means there is no information. “~” is used for typical values; otherwise, minimum or maximum are given. The terminology descriptions are not standardized. PQS names are based on their properties and grade names are derived from a possible chemistry or OEM description. The properties listed here encompass those presented in multiple sources and may or may not be associated with any one specific commercial grade.W-28, B-32, H-33, G-33, L-28, S-67, S-66, Y-12, B-33

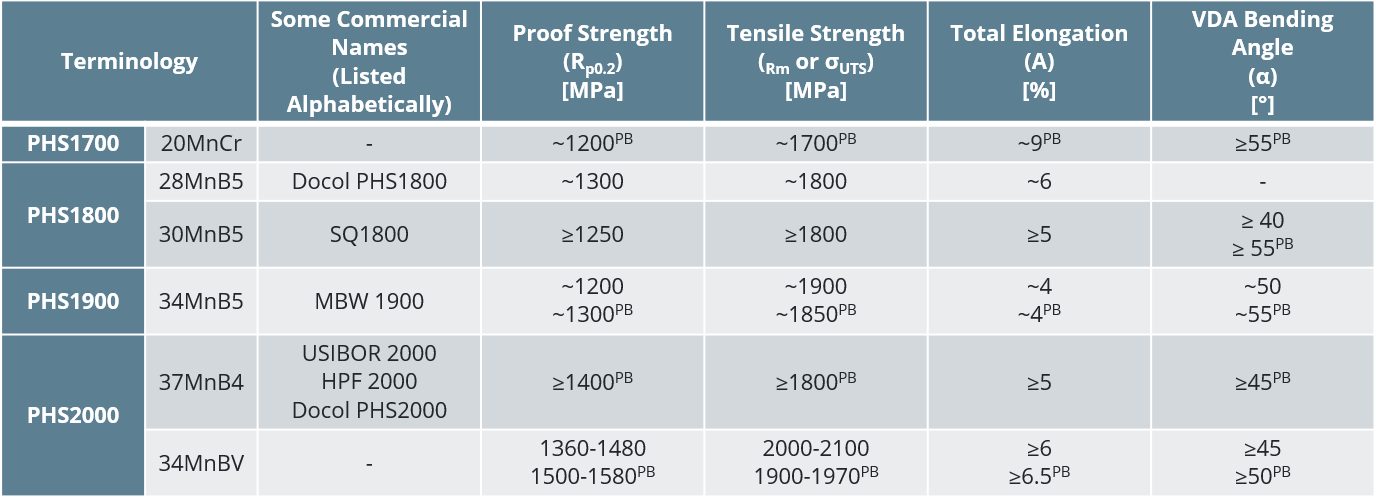

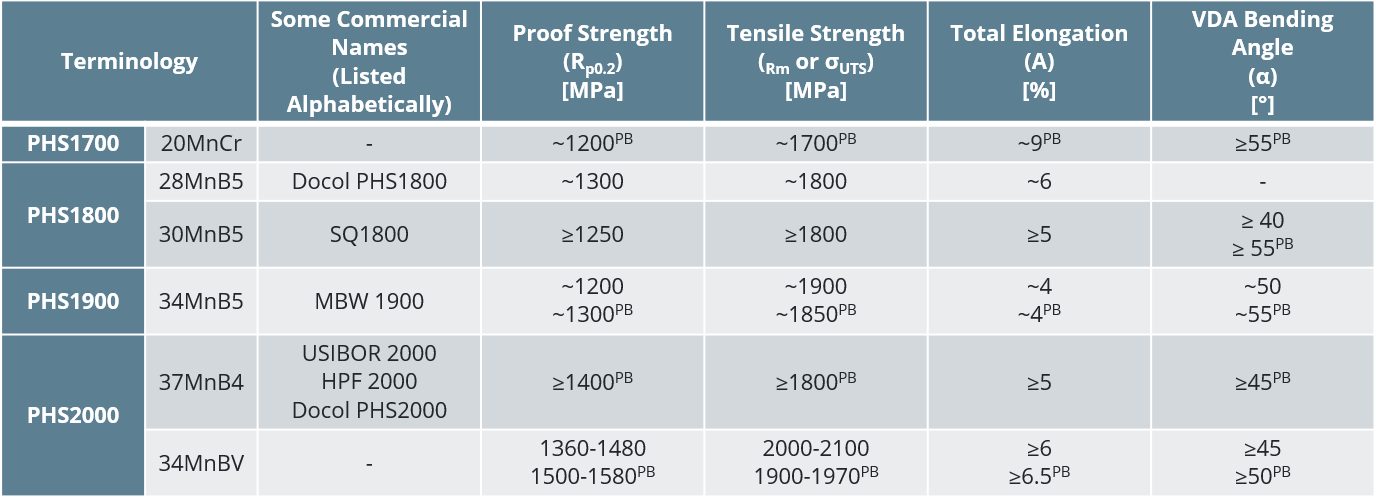

Table 5: Mechanical properties of higher strength PHS grades. “~” is used for typical values; otherwise, minimum or maximum are given. Superscript PB means after paint bake cycle. The terminology descriptions are not standardized. PQS names are based on their properties and grade names are derived from a possible chemistry or OEM description. The properties listed here encompass those presented in multiple sources and may or may not be associated with any one specific commercial grade.W-28, B-32, H-33, G-33, L-28, S-67, S-66, Y-12

Other Steels for Press Hardening Process

In recent years, many new steel grades are under evaluation for use with the press hardening process. Few, if any, have reached mass production, and are instead in the research and development phase. These grades include:

- Stainless steels

- Medium-Mn steels

- Composite steels

Stainless Steels

Studies of press hardening of stainless steels primarily focus on martensitic grades (i.e., AISI SS400 series).M-36, H-42, B-40, M-37, F-30 As seen in Figure 16, martensitic stainless steels may have higher formability at elevated temperatures, compared to PHS1500 (22MnB5). Other advantages of stainless steels are:

- better corrosion resistanceM-37,

- potentially higher heating rates (i.e., induction heating) F-30,

- possibility of air hardening – allowing the multi-step process — as seen in Figure 17a H-42,

- high cold formability – allowing indirect process – as seen in Figure 17b.M-37

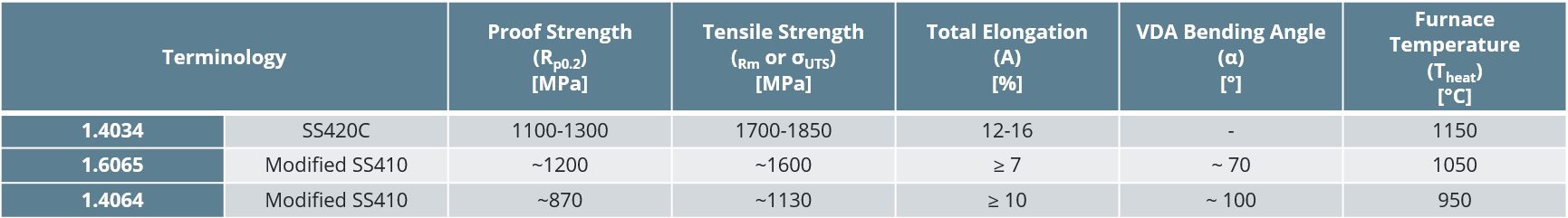

Disadvantages include (a) higher material cost, and (b) higher furnace temperature (up to around 1050-1150 °C).M-37, F-30 As of 2020, there are two commercially available stainless steel grades specifically developed for press hardening process.

Figure 16: Tensile strength and total elongation variation with temperature of (a) PHS1500 = 22MnB5M-38 and (b) martensitic stainless steel.M-36

Figure 17: (a) Critical cooling rate comparison of 22MnB5 and AISI SS410 (re-created after Citation H-42), (b) Room temperature forming limit curve comparison of DP600 and modified AISI SS410 (re-created after Citation M-37).

Final mechanical properties of stainless steels after press hardening process are typically superior to 22MnB5, in terms of elongation and energy absorbing capacity. Figure 18 illustrates engineering stress-strain curves of the commercially available grades (1.6065 and 1.4064), and compares them with the 22MnB5 and a duplex stainless steel (Austenite + Martensite after press hardening). These grades may also have bake hardening effect, abbreviated as BH0, as there will be no cold deformation.B-40, M-37, F-30

Figure 18: Engineering Stress-Strain curves of press hardened stainless steels, compared with 22MnB5 (re-created after Citations B-40, M-37, F-30, B-41).

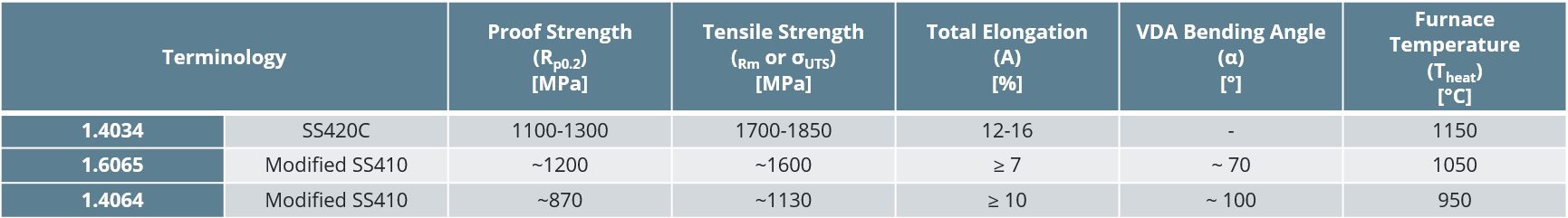

Table 6: Summary of mechanical properties of press hardenable stainless steel grades. Typical values are indicated with “~”. (Table generated from Citations B-40, M-37, F-30.)

Medium-Mn Steels

Medium-Mn steels typically contain 3 to 12 weight-% manganese alloying.D-27, H-30, S-80, R-16, K-35 Although these steels were originally designed for cold stamping applications, there are numerous studies related to using them in the press hardening process as well.H-30 Several advantages of medium-Mn steels in press hardening are:

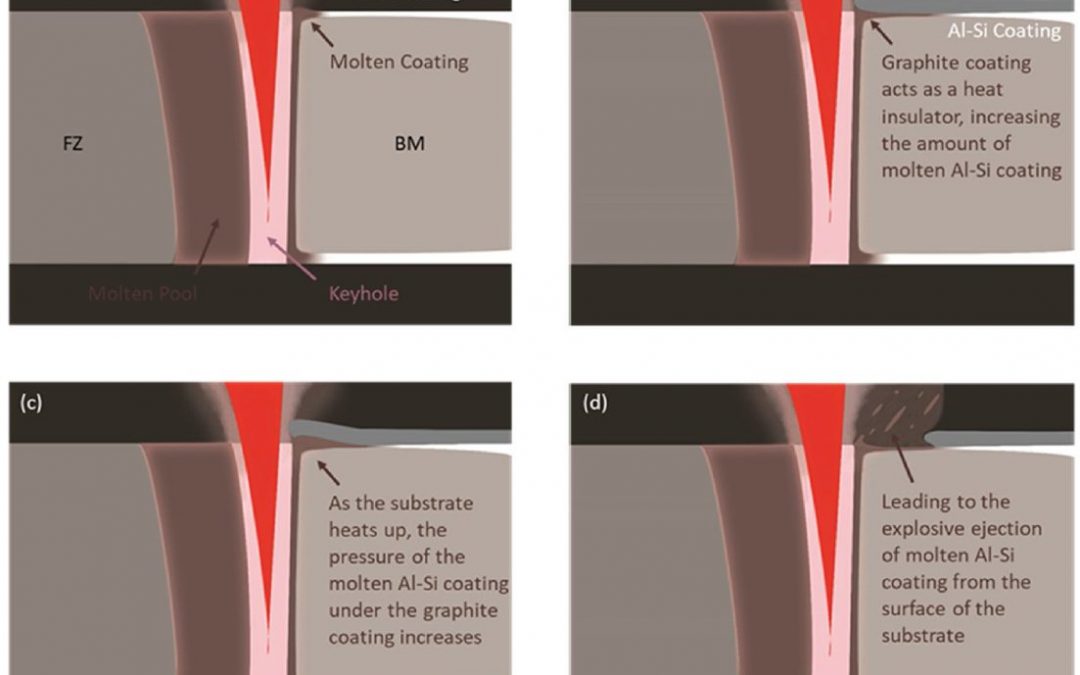

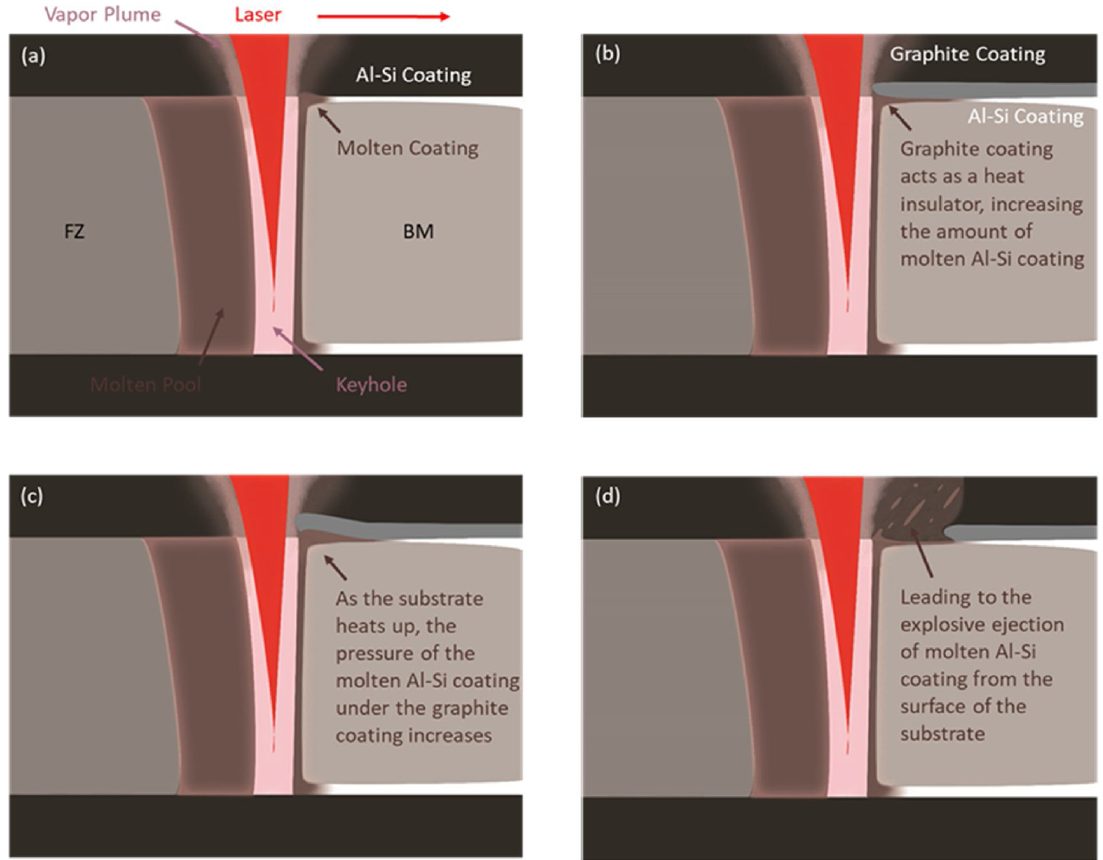

- Austenitization temperature may be significantly lower than compared to 22MnB5, as indicated in Figure 19.H-30, S-80 Thus, using medium-Mn steels may save energy in heating process.M-39 Lower heating temperature may also help reducing the liquid-metal embrittlement risk of Zn-coated blanks. It also may reduce oxidation and decarburization of uncoated blanks.S-80

- Martensitic transformation can occur at low cooling rates. Simpler dies could be used with less or no cooling channels. In some grades, air hardening may be possible. Thus, multi-step process could be employed.S-80, B-14

- Some retained austenite may be present at the final part, which can enhance the elongation, through the TRIP effect. This, in turn, improves toughness significantly.S-80, B-14

Figure 19: Effect of Mn content on equilibrium transformation temperatures (re-created after Citations H-30, B-14)

The change in transformation temperatures with Mn-alloying was calculated using ThermoCalc software.H-30 As seen in Figure 19, as Mn alloying is increased, austenitization temperatures are lowered.H-30 For typical 22MnB5 stamping containing 1.1 to 1.5 % Mn, furnace temperature is typically set at 930 °C in mass production. The multi-step material 22MnSiB9-5 has slightly higher Mn levels (2.0 to 2.4 %), so the furnace temperature could be reduced to 890 °C. As also indicated in Table 7, the furnace temperature could be further lowered in hot forming of medium-Mn steels.

A study in the EU showed that if the maximum furnace temperature is 930 °C, which is common for 22MnB5, natural gas consumption will be around 32 m3/hr. In the study, two new medium-Mn steels were developed, one with 3 wt.% Mn and the other with 5 wt% Mn. These grades had lower austenitization temperature, and the maximum furnace set temperature could be reduced to 808 °C and 785 °C, respectively. Experimental data shows that at 808 °C natural gas consumption was reduced to 19 m3/hr, and at 785 °C to 17 m3/hr.M-39 In Figure 20, experimental data is plotted with a curve fit. Based on this model, it was estimated that by using 22MnSiB9-5, furnace gas consumption may be reduced by 15%.

Figure 20: Effect of maximum furnace set temperature (at the highest temperature furnace zone) on natural gas consumption (raw data from Citation M-39)

Lower heating temperature of medium-Mn steels may also help reducing the liquid-metal embrittlement risk of Zn-coated blanks. It also may reduce oxidation and decarburization of uncoated blanks.S-80

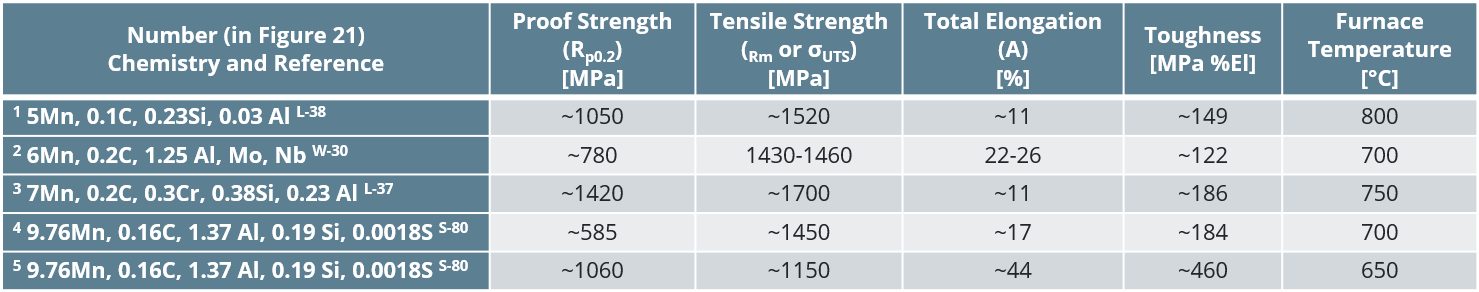

Medium-Mn steels may have high yield-point elongation (YPE), with reports of more than 5% after hot stamping. Mechanical properties may be sensitive to small changes in temperature profile. As seen in Figure 21, all studies with medium-Mn steel have a unique stress-strain curve after press hardening. This can be explained by:

- differences in the chemistry,

- thermomechanical history of the sheet prior to hot stamping,

- heating rate, heating temperature and soaking time, and

- cooling rate.S-80

Figure 21: Engineering Stress-Strain curves of several press hardened medium-Mn steels, compared with 22MnB5. See Table 7 for an explanation of each tested material (re-created after Citations S-80,L-37, W-30, L-38).

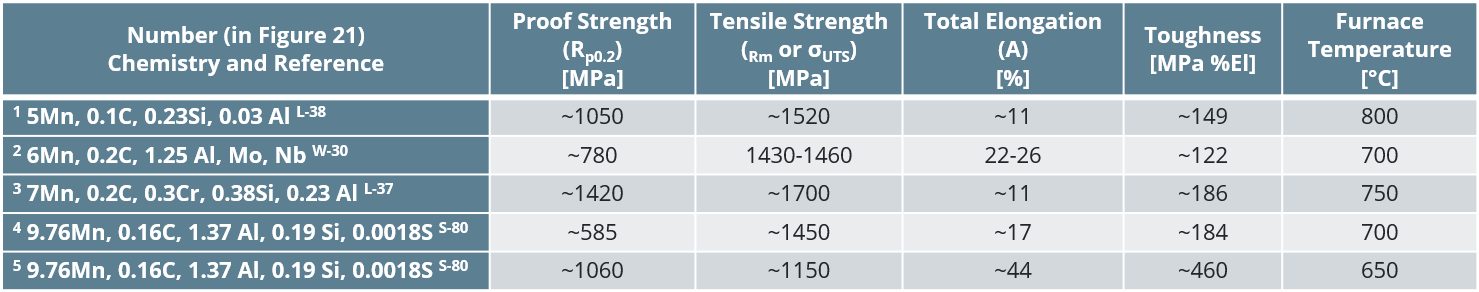

Table 7: Summary of mechanical properties of press hardenable Medium-Mn grades shown in Figure 18. Typical values are indicated with “~”. Toughness is calculated as the area under the engineering stress-strain curve. Items 4 and 5 also were annealed at different temperatures and therefore have different thermomechanical history. Note that these grades are not commercially available.L-38, W-30, L-37, S-80

Composite Steels

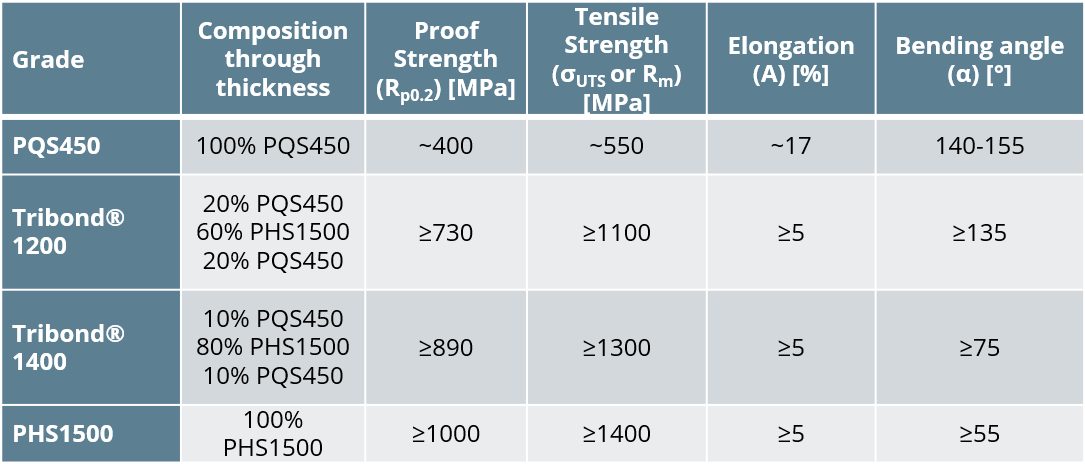

TriBond ® is the name given to a family of steel composites.T-32 Here, three slabs (one core material (60 to 80% of the thickness) and two cladding layers) are surface prepared, stacked on top of each other, and welded around the edges. The stack is hot rolled to thickness. Cold rolling could also be applied. Initially, TriBond ® was designed for wear-resistant cladding and ductile core materials.

The original design was optimized for hot stamping.B-14 The core material, where bending strains are lower than the outer layers, is made from generic 22MnB5 (PHS1500). Outer layers are made with PQS450. The stack is cold rolled, annealed and AlSi coated.Z-9 Two grades are developed, differing by the thickness distribution between the layers, as shown in Figure 22.R-14

Figure 22: Sample microsections of the conventional hot stamping grade PHS1500+AS, the high strength composite Tribond® 1400 and the high energy absorbing composite Tribond® 1200. The Tribond® 1200 microsection is experimental and is taken from Citation R-14. The other two images are renditions created by the author for explanation purposes. (re-created after Citations R-14, R-15)

Total elongation of the composite steel is not improved, compared to PHS1500, as shown in Figure 23. The main advantage of the composite steels is their higher bendability, as seen in Table 8. Crashboxes, front and rear rails, seat crossmembers and similar components experience axial crush loading in the event of a crash. In axial crush, Tribond® 1200 saved 15% weight compared to DP780 (CR440Y780T-DP). The bending loading mode effects B-pillars, bumper beams, rocker (sill) reinforcements, side impact door beams, and similar components during a crash. In this bending mode, Tribond® 1400 saved 8 to 10% weight compared to regular PHS1500. Lightweighting cost with Tribond® 1400 was calculated as €1.50/kgsaved.G-37, P-26

Figure 23: Engineering Stress-Strain curves of core layer, outer layer and the composite steel (re-created after Citation P-26).

Table 8: Summary of composite steels and comparison with conventional PHS and PQS grades. Typical values are indicated with “~”. (Table re-created after Citation B-14).

* Graphs in this article are for information purposes only. Production materials may have different curves. Consult the Certified Mill Test Report and/or characterize your current material with an appropriate test (such as a tensile, bending, hole expansion, or crash test) test to get the material data pertaining to your current stock.

For more information on Press Hardened Steels, see these pages:

Back To Top

Blog, main-blog

The Beginnings of PHS Use

Press hardening, as we know it today, was developed in Luleå, Sweden, by Norrbottens Järnverks AB (abbreviated as NJA, translated as Norrbotten Iron Works). The first patent application was completed in 1973 and awarded in 1977.N-23 The technology was first commercialized in agriculture components, where the high strength of Press Hardened Steels (PHS) was favored for wear resistance.B-45

In 1984, automotive applications of PHS started with the Saab 9000 side impact door beams, as seen in Figure 1. A total of 4 parts were used in this car.A-66 The uncoated blanks were almost half the thickness of a cold stamped beam.T-26

Figure 1: Door beams of the Saab 9000 (1984-1998): (a) A see-through car in Saab MuseumS-82, (b) the hot stamped part.L-42

The majority of the PHS parts were door beams through the mid-1990s, with approximately 6 million beams produced in 1996. By this time, the demand for bumper beams was also increasing.F-31 By the end of 1996, the European New Car Assessment Program (EuroNCAP) was formed, which increased the pressure on the OEMs for improved crashworthiness.T-26 In 1998, both the new Volvo S80L-44 and Ford Focus5 were equipped with Press Hardened bumper beams.

The year 1998 saw the development of one of the most important breakthroughs in Press Hardening technology. French steel maker Usinor developed an aluminum-silicon (AlSi) pre-coated steel, commercialized as Usibor 1500 (indicating the typical tensile strength, 1500 MPa.C-24, L-39 In 2000, BMW rolled out its new 3 series convertible. In this vehicle, the A-pillar is made from 3 mm thick uncoated, PHS sheet. This was BMW’s first PHS application, and one of the first PHS A-pillar reinforcement.S-83, S-84 Accra started delivering roll formed PHS components for the Volvo V70, initially an optional 3rd row seating support. Approximately 10,000 parts/year were supplied.G-28

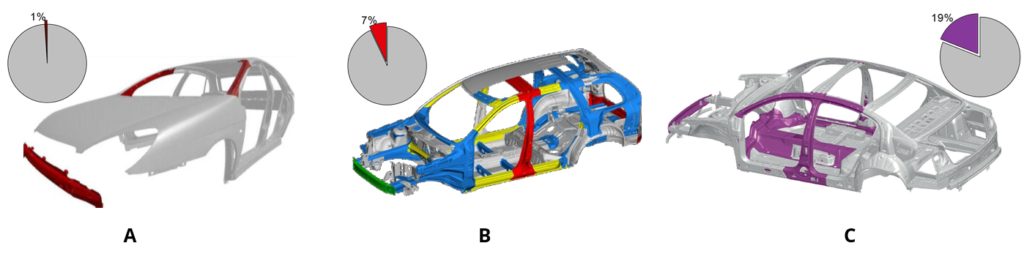

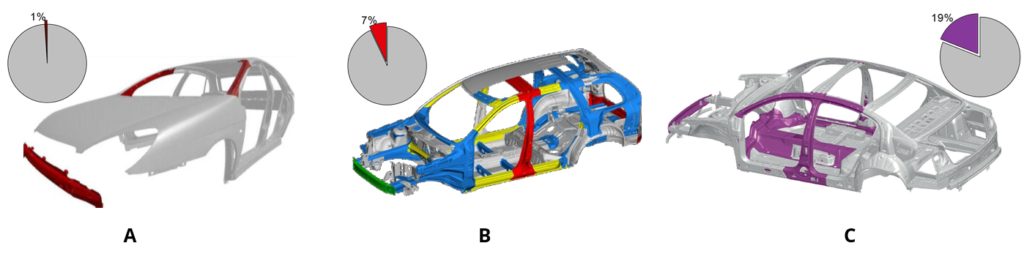

AlSi coated steel was first hot stamped at a French Tier 1 supplier, Sofedit.V-15 This grade was first used in the front bumper beam of the 2nd Generation Renault Laguna (2000-2007). Laguna 2 was the first car to receive a 5-star safety rating from Euro NCAP.V-10 AlSi coated blanks were also used in PSA Group’s Citroën C5 (1st Gen: 2001-2007) in the front bumper beam, and the A-pillars. These three parts weighed a total of 4.5 kg, approximately 1% of the total BIW weight, Figure 2a. About one month later, PSA Group started production of the compact hatchback Peugeot 307, which had five hot stamped components (A- and B-pillars and rear bumper beam). Unlike the Citroën C5, these parts were uncoated. The total weight was 12 kg, corresponding to 3.4% of the BIW weight.R-17, P-27

Figure 2: Increase in press hardened component usage: (a) 2001 Citroën C5P-27, (b) 2002 Volvo XC90L-29 and (c) 2005 VW Passat.H-50

Volvo started producing the XC90 SUV in 2002. The body-in-white with doors and closures weighed 531 kg.B-44 A total of 10 parts, weighing 37 kg are either roll formed or direct stamped PHS. This accounts for approximately 7% of the BIW weight.L-43 During its time, this was the highest use of PHS in car bodies. In Figure 2b, the Press Hardened components other than the 2nd row seat frame, which is a load bearing body part, are shown.

Accelerated Use and Globalization

The use of press hardened parts increased rapidly after the introduction of the VW Passat in 2005. This car had approximately 19% of its BIW (by weight) made from press hardened steels, Figure 2c. Some parts in this car saw the first use of varnish coated blanks in a two-step hybrid process. Three parts were produced using either an indirect or hybrid process, including the transmission tunnel.H-50

Following are a few highlights of PHS use in vehicle applications during this time period :

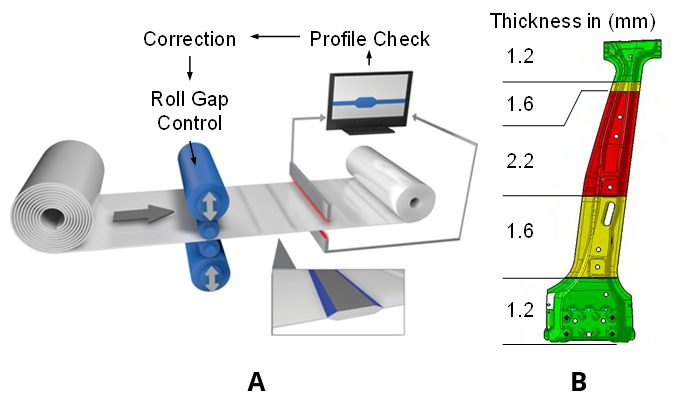

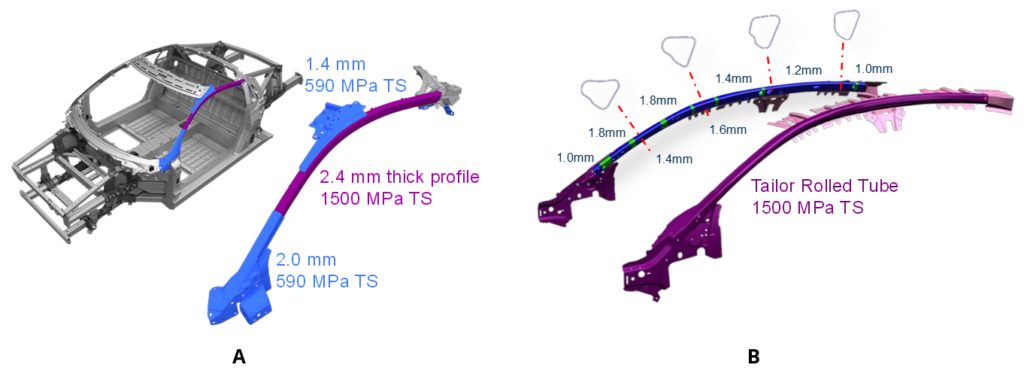

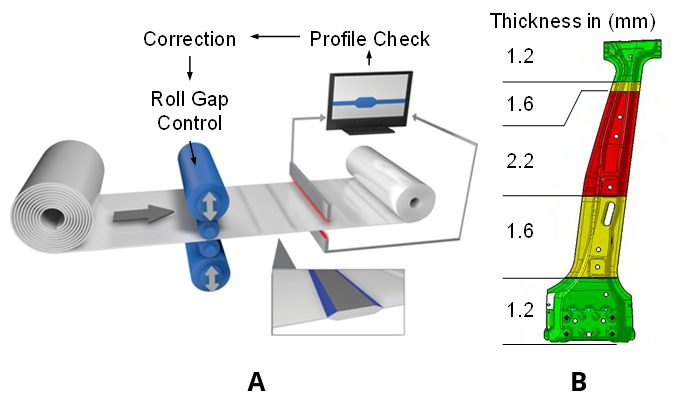

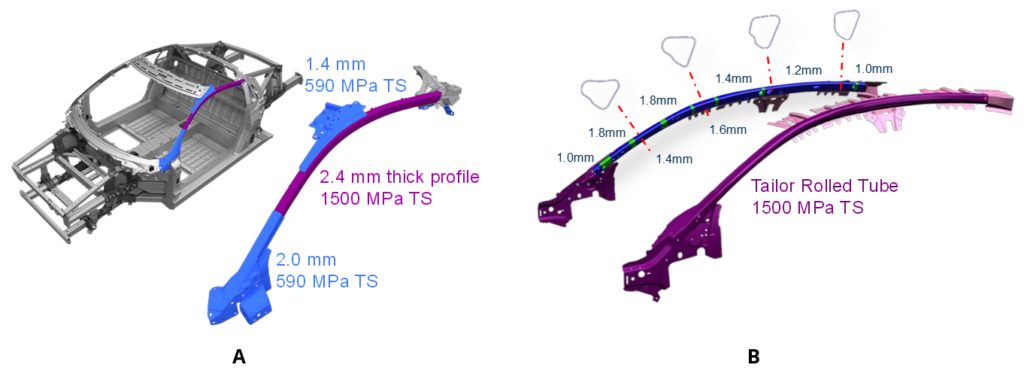

- In 2006, the Dodge CaliberK-37 and BMW X5P-28 were among the first cars to have tailor-rolled and Press Hardened components in their bodies (Figure 3).

Figure 3: (a) Tailor Rolling ProcessZ-5, (b) B-pillar of BMW X5 (2nd Gen: 2006-2013).P-28

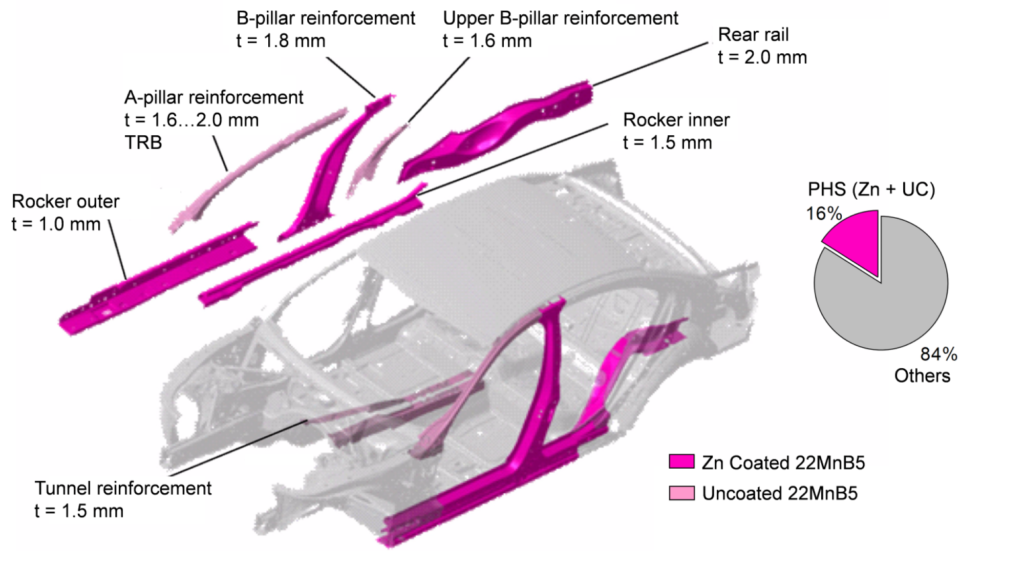

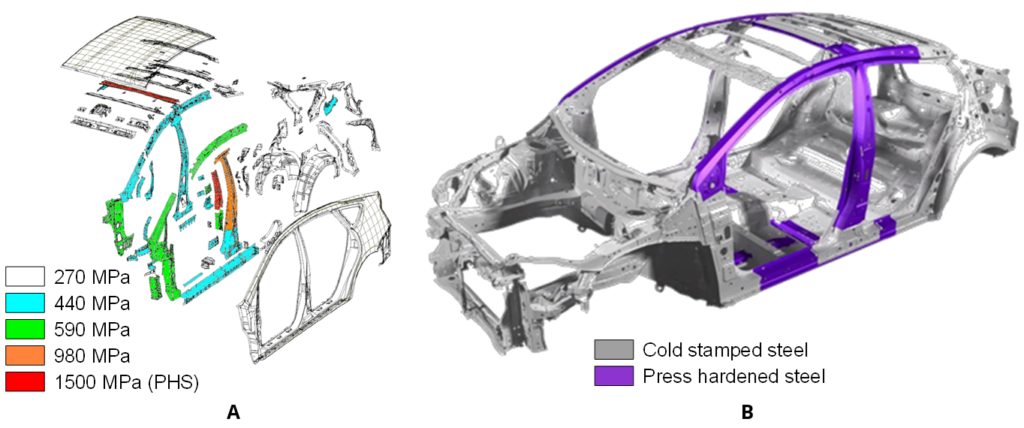

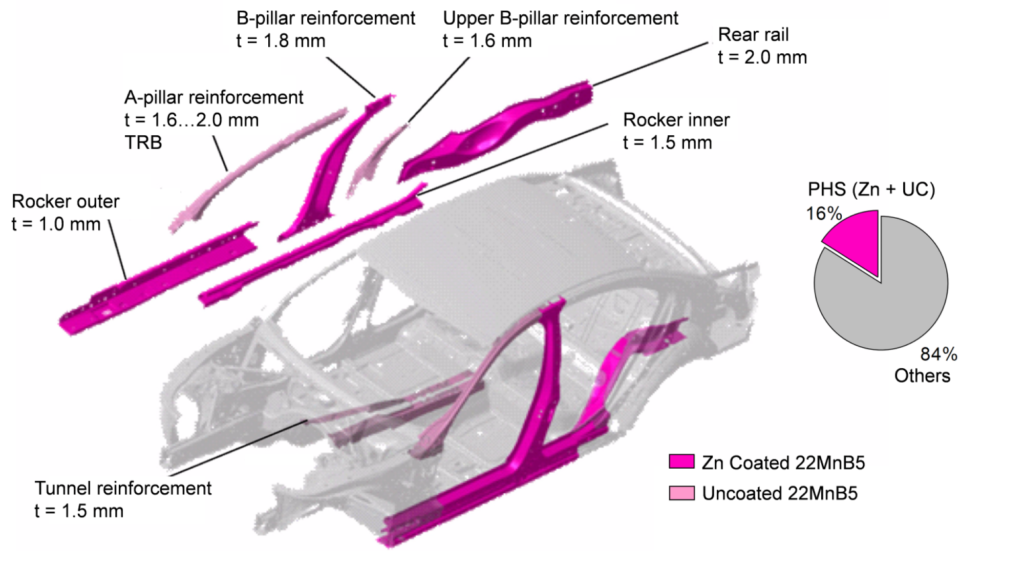

- BMW 7 Series (5th Gen: 2008-2015) became the first car to have Zn-coated Press Hardened components in its body-in-white. The car also contained uncoated parts, as shown in Figure 4 (next page). The total PHS usage in this car was approximately 16%.P-20

Figure 4: PHS usage in BMW 7 Series (5th Gen: 2008-2015) (re-created using P-20).

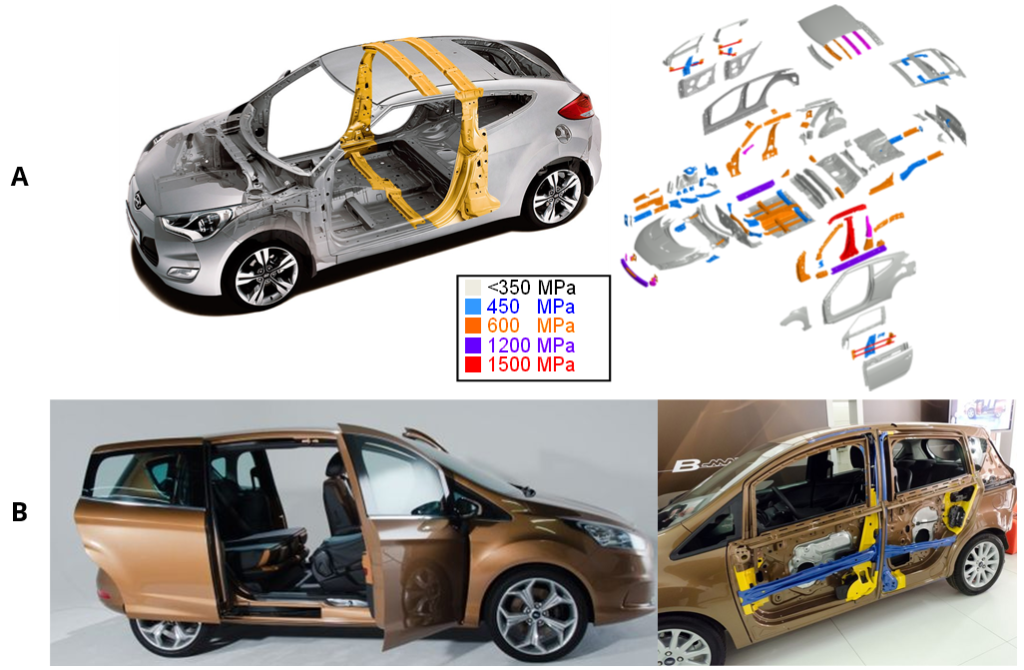

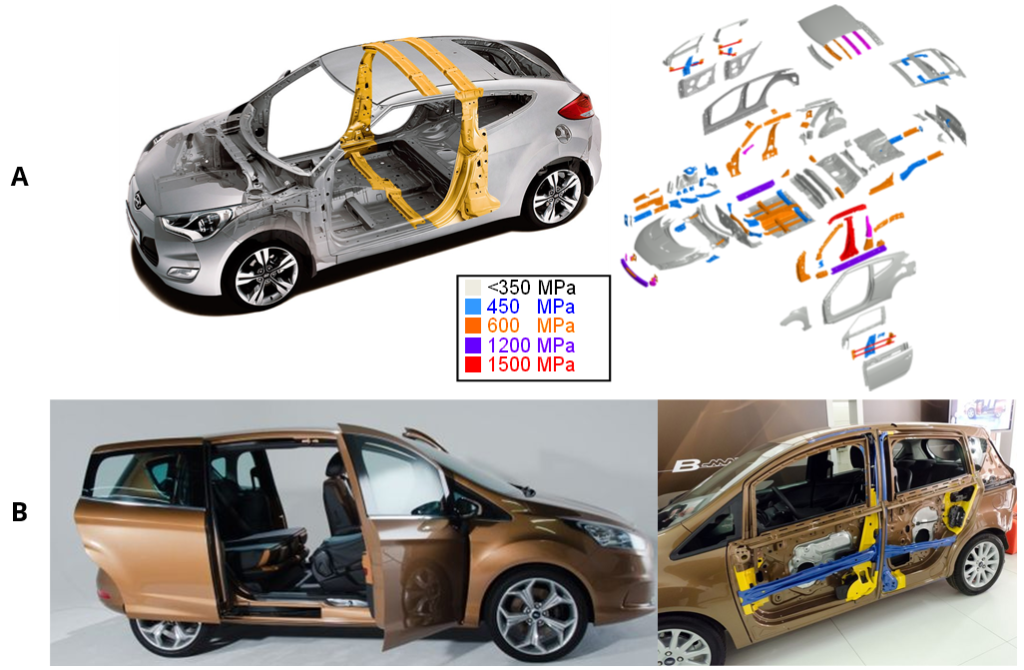

- Press hardening also allowed car makers to create unconventional cars. In 2011, Hyundai rolled out the 1st generation Veloster, a 3-door coupé (also known as 2+1, with one door on the driver side and 2 doors on the passenger side), and as such containing axisymmetric front doors. Thus, the car could not have a full B-ring, as illustrated in Figure 5a.B-14, R-19 Another unconventional design was the Ford B-Max subcompact MPV sold in Europe between 2012 and 2017. The car had conventional swing doors in the front and two sliding rear doors. A PHS B-pillar was integrated in the doors, providing ease of ingress. Its PHS components (integrated B-pillar in front and rear doors, door beams and cantrail) are shown with blue color in Figure 5b.B-14, L-45

Figure 5: Unconventional car designs with PHS: (a) Hyundai Veloster, asymmetric 2+1 doors coupé (re-created after Citation R-19), and (b) Ford B-Max, sub-compact MPV with integrated B-pillars in the doors.L-45

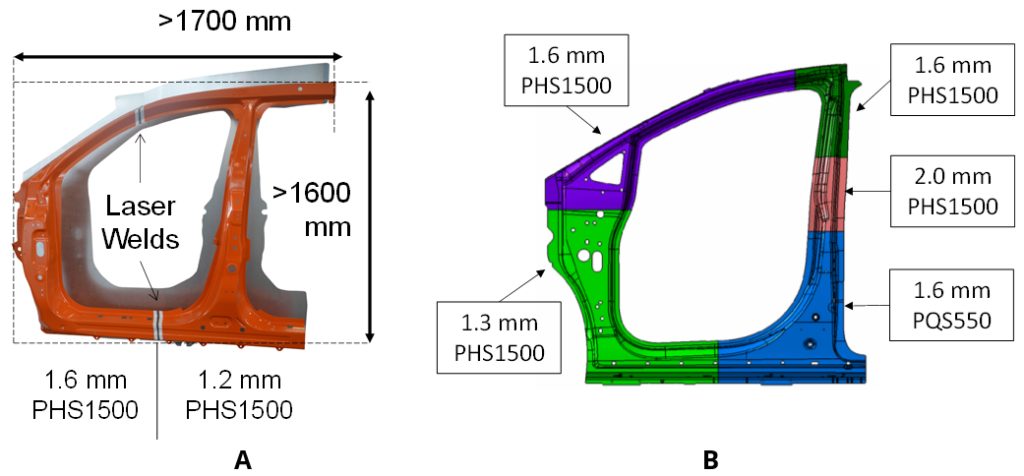

In 2013, the Acura MDX (3rd Gen: 2013-2020) became the first car to have a Hot Stamped door ring. The part was a tailor welded blank comprised of two sub-blanks, as shown in Figure 6a. The design saved about 6.2 kg weight per car and had high material utilization ratio thanks to sub-blank nesting optimization.A-67, M-46 One of the most recent PHS applications was in 2017 Chrysler Pacifica with 5 sub-blanks, as shown in Figure 6b. This car also has a PQS550 sub-blank at the lower B-pillar region.D-28

Figure 6: Hot stamped door rings: (a) First application in 2013 Acura MDX had 2 sub-blanks, (b) a more recent application in 2017 Chrysler Pacifica has five sub-blanks with PQS550 at the lower B-pillar (re-created after Citations B-14, A-67, D-28).

- Tubular hardened steels have been long used in car bodies, with minimal forming. Since 2013, a special 3-D hot bending and quenching (3DQ) process has been employed. One of the earliest uses of this technology was Mazda Premacy (known as Mazda 5 in some markets). The same process was also used in making the A-pillars of the Acura NSX (Honda NSX in some markets, 2016-present), as seen in Figure 7a.H-29 Since 2018, tubular parts formed with internal pressure, called form blow hardened parts, are used in the Ford Focus (4th Generation) (Figure 7b) and Jeep Wrangler (4th Generation).B-16, B-17

Figure 7: Tubular hardened steel usage in A-pillars of: (a) 2015 Acura NSXH-29, (b) 2018 Ford Focus.B-16

PHS Use in xEVs: Hybrid Electric, Battery Electric,

Plug-in Hybrid Electric & Fuel Cell Electric Vehicles

The first commercially available Hybrid Electric Vehicle (HEV) was the Toyota Prius (1st Gen: 1997-2003). The second-generation Prius (2003-2009) had very few Press Hardened components, as shown with red color in Figure 8a. This was the first time Toyota used hot stamped components.M-47 The third generation Prius (2009-2015) had approximately 3% of its BIW Press Hardened. In the 4th generation Prius released in 2015, the share of >980 MPa steels has risen to 19%.U-10 Figure 8b shows the Press Hardened parts in this latest Prius.K-38

Figure 8: PHS usage in Toyota Prius: (a) 2nd generation (2003-2009) and (b) 4th generation (2015-present) (re-created after Citations M-47 and K-38)

The 2012 Tesla Model S and Model X launched using aluminium bodies, with PHS reinforcements in the pillars and the bumpers. Model S is known to have a roll-formed PHS bumper beam. High volume Model 3 and Model Y have a significant amount of press hardened components in their bodies.T-35

In 2011, General Motors started production of its first Plug-in Hybrid Electric Vehicle (PHEV), the Chevrolet Volt (known as Opel Ampera in EU and Vauxhall Ampera in the UK). This car had six Hot Stamped components, including A and B pillars, accounting for slightly over 5% of the BIW mass.P-29

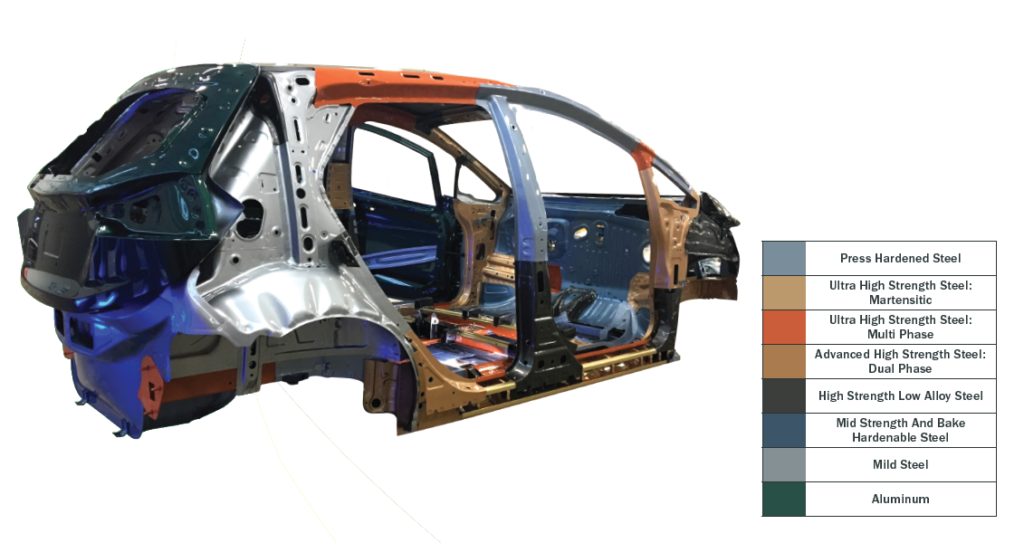

The smaller BEV Chevrolet Bolt, launched in 2017, had aluminum closures, but a steel-intensive BIW that is 80% steel, 44% of which is Advanced High-Strength Steels including 11.8% PHS. Figure 9.A-69

Figure 9: Chevrolet Bolt Body Structure and Steel Content.A-69

In December 2020, Hyundai announced their new electric platform, E-GMP. The platform will utilize Press Hardened steel components to secure the batteries.H-52

Automakers have turned to PHS to manage the extra load of Fuel Cell powertrains as well. The first-generation Toyota Mirai had only Press Hardened B-pillars, cantrails and lateral floor members.T-38 The second generation has a number of parts with PHS in its under body as well.T-39

In 2018, Hyundai Nexo became the first fuel-cell car to be tested by EuroNCAP, achieving a 5-Star rating. The car has PHS A- and B-pillars, rocker reinforcements, and several under body components, as seen in Figure 10.H-53

Figure 10: Press hardened steel usage in Hyundai Nexo Fuel Cell vehicle: (a) side view and (b) top view (re-created after Citation H-53).

Did you enjoy this story? You can find a much more detailed article here in the Guidelines with many more vehicle examples and history data.