Every industry has its own jargon. In certain settings, these words might be necessary – you wouldn’t want a cardiologist talking to a gastroenterologist about boo-boos and upset tummies. But when these professionals talk with their patients, it’s sometimes necessary...

Martensite

Metallurgy of Martensitic Steels Case Study: Using Martensitic Steels as an Alternative to Press Hardening Steel – Laboratory Evaluations Case Study: Martensitic Steels as an Alternative to Press Hardening Steel – Automotive Production Examples with Springback...

Press Hardening Steel Grades

Introduction PHS Grades with Tensile Strength Approximately 1500 MPa Grades with Higher Ductility PHS Grades Over 1500 MPa Other Steels for Press Hardening Process Stainless steels Medium-Mn steels Composite steels Introduction Press hardening steels (PHS) are...

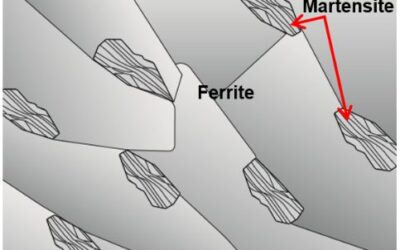

Dual Phase

Dual Phase (DP) steels have a microstructure consisting of a ferritic matrix with martensitic islands as a hard second phase, shown schematically in Figure 1. The soft ferrite phase is generally continuous, giving these steels excellent ductility. When these steels...

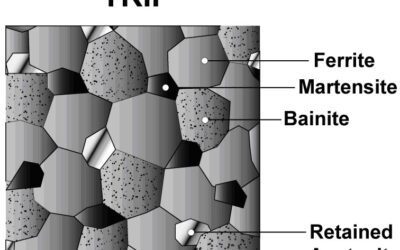

Transformation Induced Plasticity (TRIP)

Metallurgy Transformation Induced Plasticity Effect topofpage Metallurgy The microstructure of Transformation Induced Plasticity (TRIP) steels contains a matrix of ferrite, with retained austenite, martensite, and bainite present in varying amounts. Production of TRIP...

Complex Phase

Complex Phase (CP) steels combine high strength with relatively high ductility. The microstructure of CP steels contains small amounts of martensite, retained austenite and pearlite within a ferrite/bainite matrix. A thermal cycle that retards...

Ferrite-Bainite

Ferrite-Bainite (FB) steels are hot rolled steels typically found in applications requiring improved edge stretch capability, balancing strength and formability. The microstructure of FB steels contains the phases ferrite and bainite. High elongation is associated...