Resistance Spot Welding

Parameter Guidelines

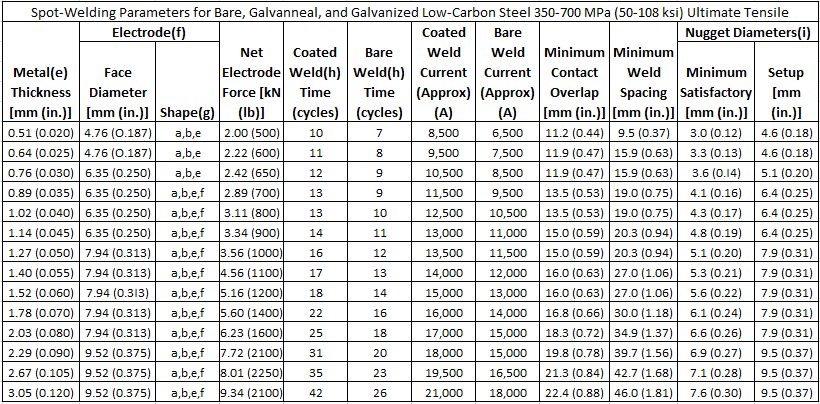

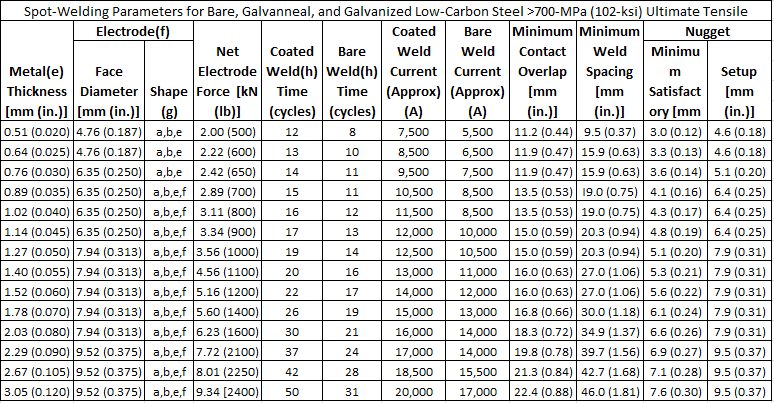

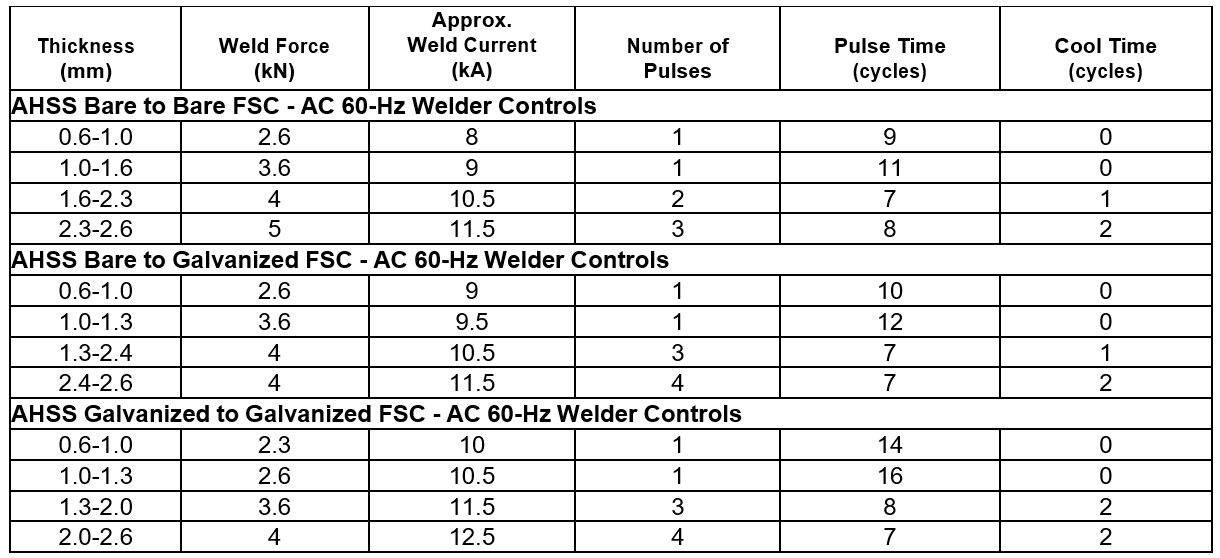

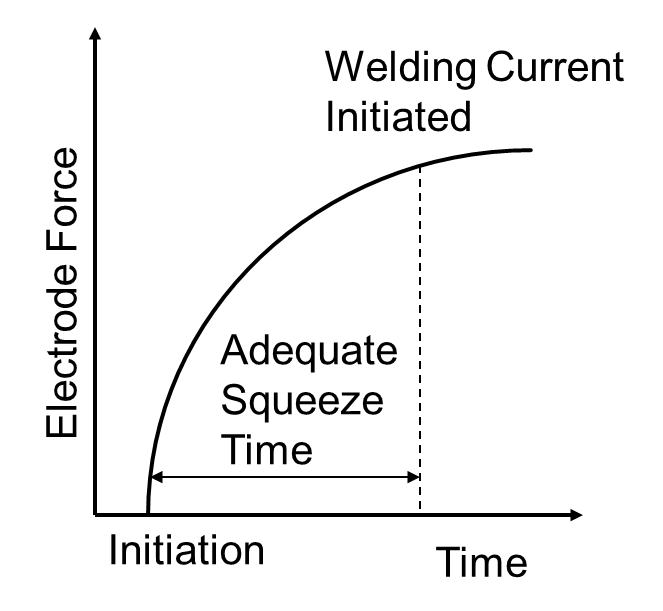

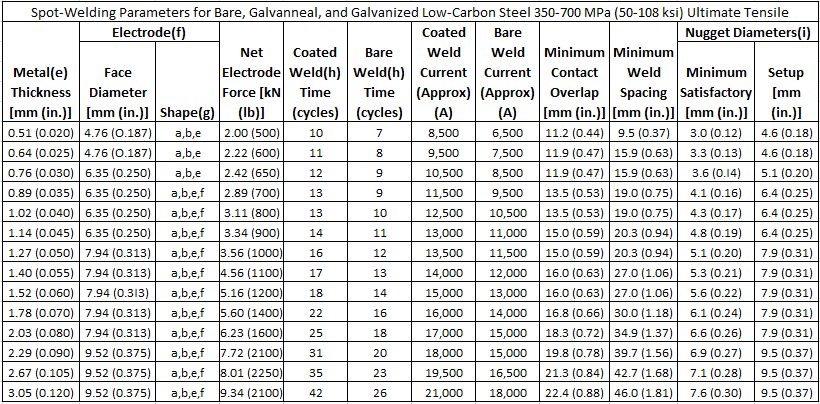

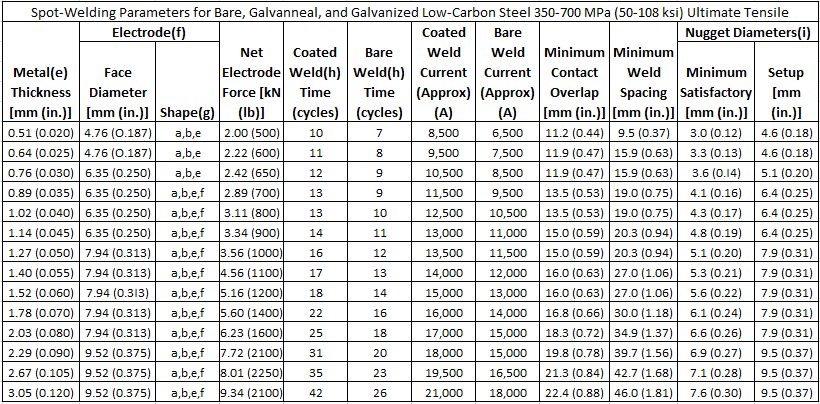

In summary, Tables 1 and 2 provide the AWS C1.1 Spot Welding Parameter Guidelines link to Recommended Practices for Resistance Welding. These general guidelines can be used to approximate which parameters can be used to begin the Resistance Spot Welding (RSW) process of a specific part thickness. From the recommended parameters, changes can be made on a specific stack-up to ensure an acceptable strength and nugget size for a particular application. Additionally, more complicated RSW parameter guidelines using a pulsation welding schedule with AC 60 Hz for welding AHSS is included in Table 3.

Table 1: Spot welding parameters for low-carbon steel 350-700 MPa (AHSS).A-14

- Use of coated parameters recommended with the presence of a coating at any faying surface.

- These recommendations are based on available weld schedules representing recommendations from resistance welding equipment suppliers and users.

- For intermediate thicknesses parameters may be interpolated.

- Minimum weld button shear strength determined as follows:

- ST = ((-8.83×10-7 × S2 + 1.34×10-3 × S + 1.514) × S × 4t1.5)/1000

- ST = Shear Tension Strength (kN)

- S = Base Metal Tensile Strength (MPa)

- t = Material Thickness (mm)

- Metal thicknesses represent the actual thickness of the sheets being welded. In the case of welding two sheets of different thicknesses, use the welding parameters for the thinner sheet.

- Welding parameters are applicable when using electrode materials included in RWMA Classes 1 , 2, and 20.

- Electrode shapes listed include: A-pointed, B-domed, E-truncated, F-radiused. Figure 2 shows these shapes.

- The use of Type-B geometry may require a reduction in current and may result in excessive indentation unless face is dressed to specified diameter.

- The use of Type F geometry may require an increase in current.

- Welding parameters are based on single-phase AC 60 Hz equipment.

- Nugget diameters are listed as:

- Minimum diameter that is recommended to be considered a satisfactory weld.

- Initial aim setup nugget diameter that is recommended in setting up a weld station to produce nuggets that consistently surpass the satisfactory weld nugget diameter for a given number of production welds.

Table 2: Spot welding parameters for low-carbon steel >700 MPa (AHSS). A-14

- Use of coated parameters recommended with the presence of a coating at any faying surface.

- These recommendations are based on available weld schedules representing recommendations from resistance welding equipment suppliers and users.

- For intermediate thicknesses parameters may be interpolated.

- Minimum weld button shear strength determined as follows:

- ST = ((-8.83×10-7 × S2 + 1.34×10-3 × S + 1.514) × S × 4t1.5)/1000

- ST = Shear Tension Strength (kN)

- S = Base Metal Tensile Strength (MPa)

- t = Material Thickness (mm)

- Metal thicknesses represent the actual thickness of the sheets being welded. In the case of welding two sheets of different thicknesses, use the welding parameters for the thinner sheet.

- Welding parameters are applicable when using electrode materials included in RWMA Classes 1, 2, and 20.

- Electrode shapes listed include: A-pointed, B-domed, E-truncated, F-radiused. Figure 2 shows these shapes.

- The use of Type-B geometry may require a reduction in current and may result in excessive indentation unless face is dressed to specified diameter.

- The use of Type F geometry may require an increase in current.

- Welding parameters are based on single-phase AC 60 Hz equipment.

- Nugget diameters are listed as:

- Minimum diameter that is recommended to be considered a satisfactory weld.

- Initial aim setup nugget diameter that is recommended in setting up a weld station to produce nuggets that consistently surpass the satisfactory weld nugget diameter for a given number of production welds.

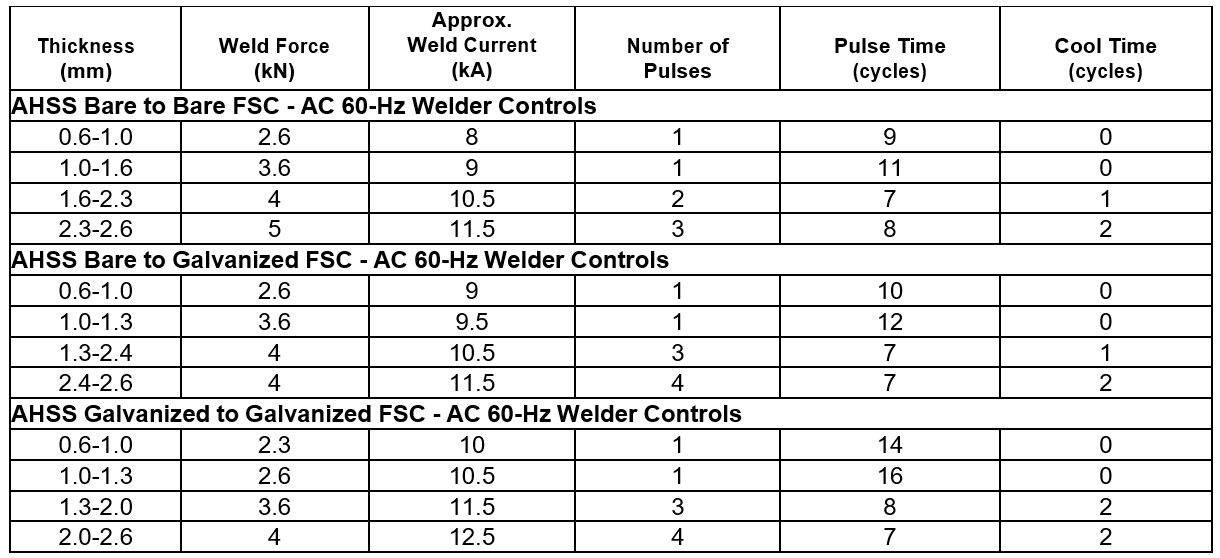

Table 3: AHSS bare-to-bare, bare-to-galvanized, Galvanized-to-galvanized RSW parameters for pulsating AC 60 Hz.A-14

Heat, Material and Thickness Balances

The heat input in Resistance Spot Welding (RSW) is defined as:

Heat Input = I2Rt

where: I is welding current

R is total resistance, and

t is weld time

The heat input must be changed depending on the gauge and grade of the steel. Compared to low strength steel at a particular gauge, the AHSS at the same gauge will need less current. Similarly, the thin gauge material needs less current than thick gauge. Controlling the heat input according to the gauge and grade is called heat balance in RSW.

For constant thickness, Table 1 shows steel classification based on strength level. With increasing group numbers, higher electrode force, longer weld time, and lower current are required for satisfactory RSW. Material combinations with one group difference can be welded with little or no changes in weld parameters. Difference of two or three groups may require special considerations in terms of electrode cap size, force, or type of power source.

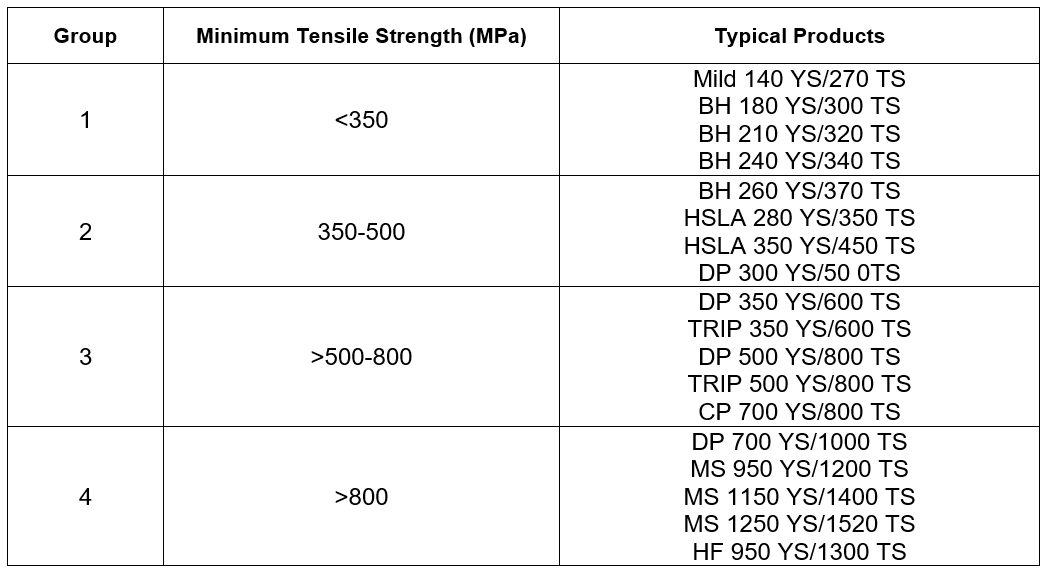

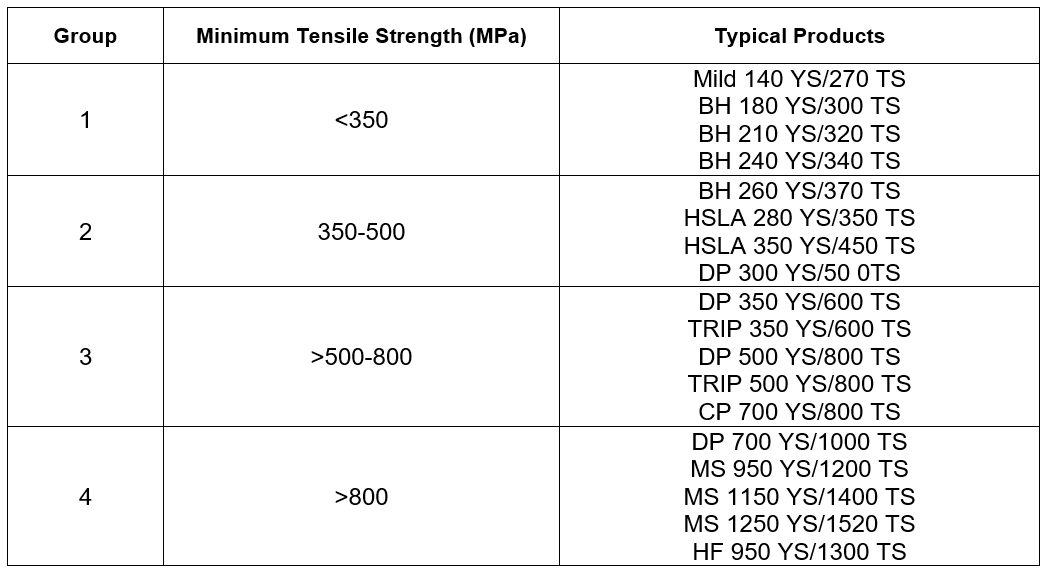

Table 1: Steel classification for RSW purposes.A-11

For a particular steel grade, changes in thickness may require adoption of special schedules to control heat balance. When material type and gauge are varied together, specific weld schedules may need to be developed. Due to the higher resistivity of AHSS, the nugget growth occurs preferentially in AHSS. Electrode life on the AHSS-side may be reduced due to higher temperature on this side. In general, electrode life when welding AHSS may be similar to mild steel because of lower operating current requirement due to higher bulk resistivity in AHSS. This increase in electrode life may be offset in production due to poor part fit up created by higher AHSS springback. Frequent tip dressing will maintain the electrode tip shape and help achieve consistently acceptable quality welds.

Welding Current Mode

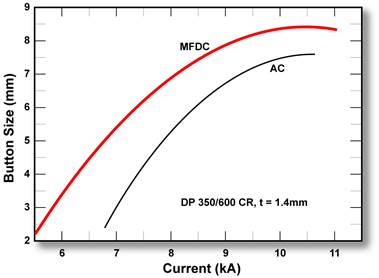

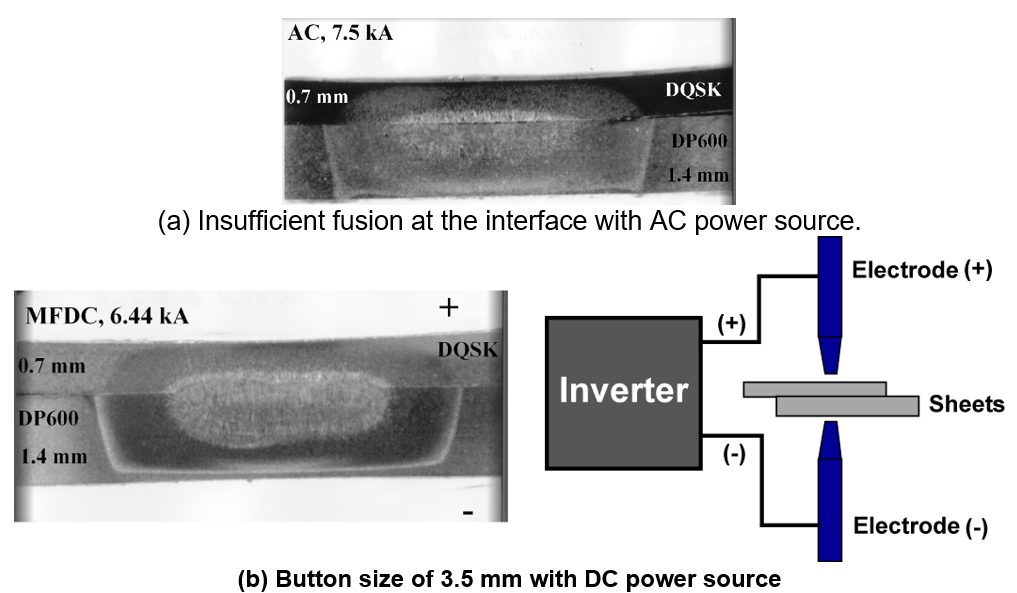

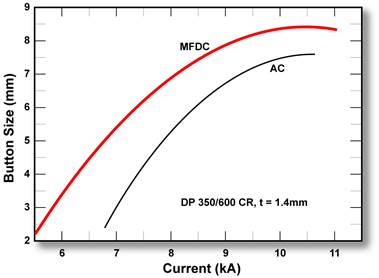

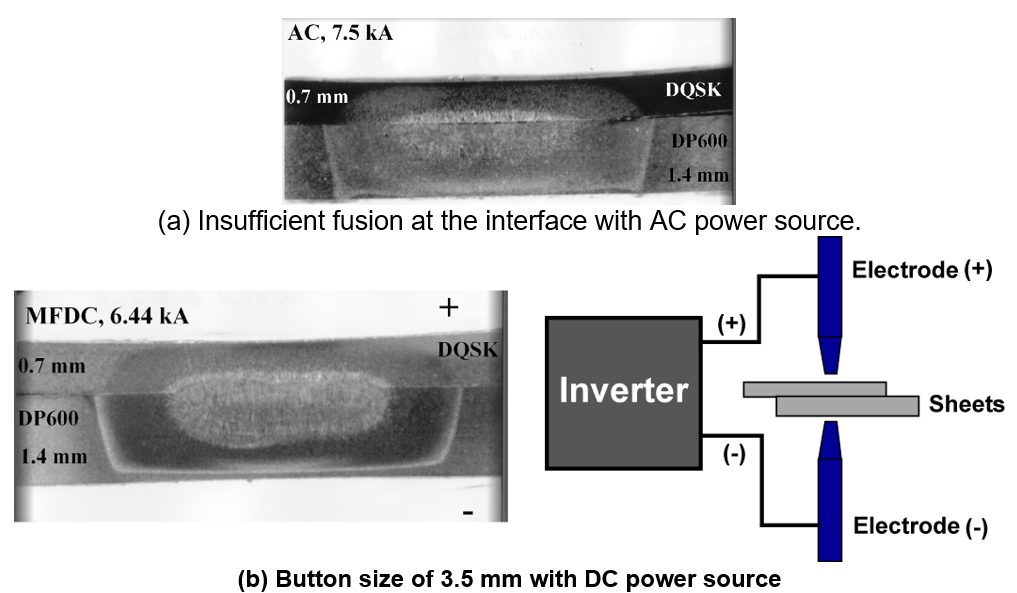

AHSS can be welded with power sources operated with either AC or DC types (Figure 1). Middle-Frequency Direct-Current (MFDC) has an advantage over conventional AC due to both unidirectional and continuous current. These characteristics assist in controlling and directing the heat generation at the interface. Current mode has no significant difference in weld quality. It should be noted that both AC and DC can easily produce acceptable welds where thickness ratios are less than 2:1. However, some advantage may be gained using DC where thickness ratios are over 2:1, but welding practices must be developed to optimize the advantages. It also has been observed that nugget sizes are statistically somewhat larger when using DC welding with the same secondary weld parameters than with AC. Some studies have shown that welding with MFDC provides improvements in heat balance and weld process robustness when there is a thickness differential in AHSS (as shown in Figure 2). DC power sources have been reported to provide better power factors and lower power consumption than AC power sources. Specifically, it has been reported that AC requires about 10% higher energy than DC to make the same size weld.L-7

Figure 1: Range for 1.4-mm DP 350/600 CR steel at different current modes with a single pulse.L-2

Figure 2: Effect of current mode on dissimilar-thickness stack-up.L-2

Consult safety requirements for your area when considering MFDC welding for manual weld gun applications. The primary feed to the transformers contains frequencies and voltages higher than for AC welding.

Back To Top

Resistance Spot Welding

In general, if any type of AHSS [Dual-Phase (DP), Transformation-Induced Plasticity (TRIP), Complex Phase (CP), Ferrite Bainite (FB), or Martensitic (MS)] is used for the first time, the user should take the welding schedules applied to mild steel and then:

- Increase the electrode force by 20% or more depending on Yield Strength.

- Increase weld time as appropriate.

If these changes are insufficient, try these additional changes:

- A multi-pulse welding schedule (several pulses or post heating).

- Larger tip diameter and/or change the type of electrode.

- Increase the minimum weld size.

When resistance welded, AHSS require less current than conventional mild steel or HSLA because AHSS have higher electrical resistivity. Therefore, current levels for AHSS are not increased and may even need to be reduced depending on material chemical composition. However, most AHSS grades may require higher electrode forces for equivalent thickness of mild steels because electrode force depends on material strength. If thick mild steel or HSLA steel (of the same thickness) is replaced by an equivalent thickness of AHSS, the same forces may be required during assembly welding.

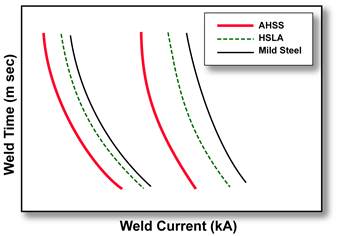

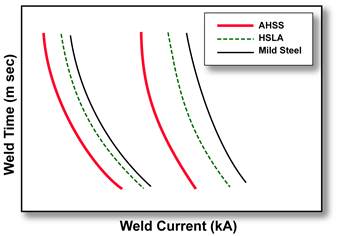

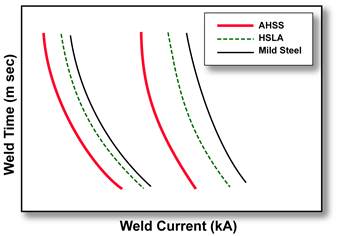

AHSS often have tighter weld windows (welding parameters that give acceptable welds) when compared to mild steels, as shown in the Figure 1.

Figure 1: Schematic weld lobes for AHSS, HSLA, and mild steel with a shift to lower currents with increased strength.

The current range (kA) for AHSS of 600-1400MPa during RSW is shown in Figures 2 and 3. The process window for Resistance Spot Welding of AHSS is influenced by the electrode force and welding time used in a major way. The current range increases by an average of 500 A for every additional 500 N of electrode force (Figure 2). The current range also increases by an average of 250 A for each additional 40 ms of welding time (Figure 3). Extra amounts of electrode force and welding time lead to increased current range, allowing for a wider process window.

Figure 2: RSW with AHSS, current range for varying electrode force (Cap Type B 16/6, 6-mm tip diameter, single pulse, 340-ms weld time, 250-ms hold time, plug failures.).I-6

Figure 3: RSW with AHSS, current range for varying weld time (Cap Type B 16/6, 6-mm tip diameter, single pulse, 3.5-kN electrode force, 250-ms hold time, plug failures.).O-1

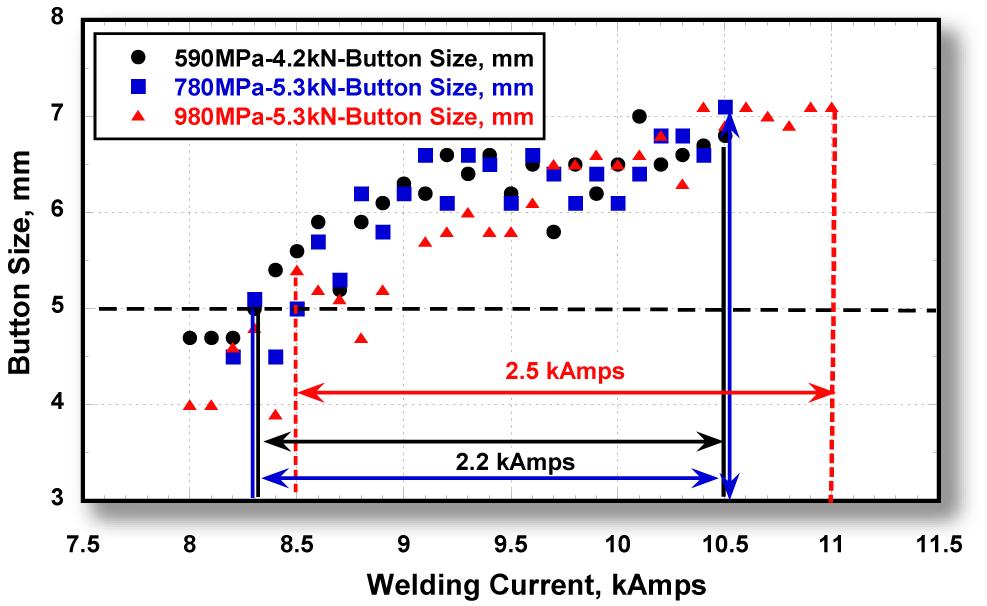

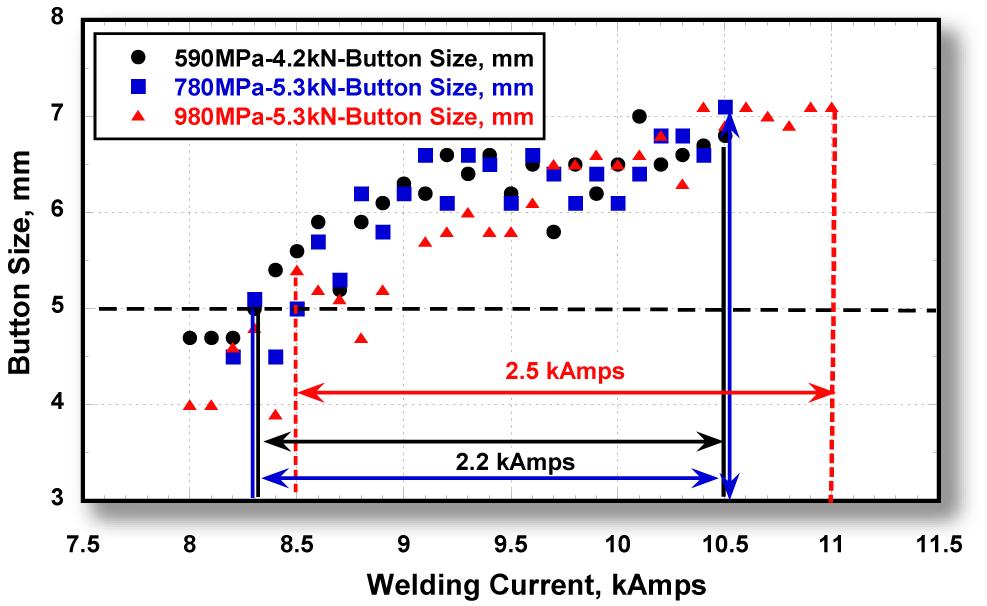

A more extensive weld studyT-5 of three DP HDGA (45/45 g/m2) coated steels showed similar welding behavior for all three steels. The 1.6-mm-thick steels were DP 340/590, DP 420/780, and DP 550/980. To characterize the welding behavior of the steels, useful current ranges and static weld tensile tests were performed. The useful current range is the difference between the welding current required to produce a minimum button size (Imin) and the current that causes expulsion of weld metal (Imax). In this study, the 4√t as the minimum button diameter was used, where “t” is the nominal sheet thickness. This is generally used in the automotive and steel industries. The weld current range was 2.2 kA for the DP 340/590 and DP 420/780 and 2.5 kA for the DP 550/980 steel (Figure 4). These current ranges are sufficiently wide to weld successfully the DP steels. The study also found no weld imperfections, which means these three DP steels are weldable with simple, easy to use welding parameters.

Figure 4: Welding current ranges for 1.6-mm DP HDGA steels with minimum tensile strengths of 590, 780, and 980 MPa.T-5

Average reported weld hardness was 380 HV (Vickers Hardness) for the DP 340/590 and 415 HV for the other two. Again, all three DP steels had similar weld hardness distributions. The study also concluded that weld fracture mode alone is not a good indicator of weld integrity and performance. The load to fracture should be considered more important in judging weld integrity.

A second studyT-6 compared two 1.6-mm-thick HDGA (45/45 g/m2) steels: DP 420/700 and TRIP 420/700. The weld current range for 18 cycles weld time was similar: 1.4 kA for the DP 420/700 and 1.5 kA for the TRIP 420/700. The average weld hardness was 400 HV for both steels. The study concluded that acceptable welds with no imperfections can be produced in both steel grades. Both steel grades are readily weldable with easily adoptable welding parameters. Weld tensile strength differences between the two steels were small and not considered statistically significant.

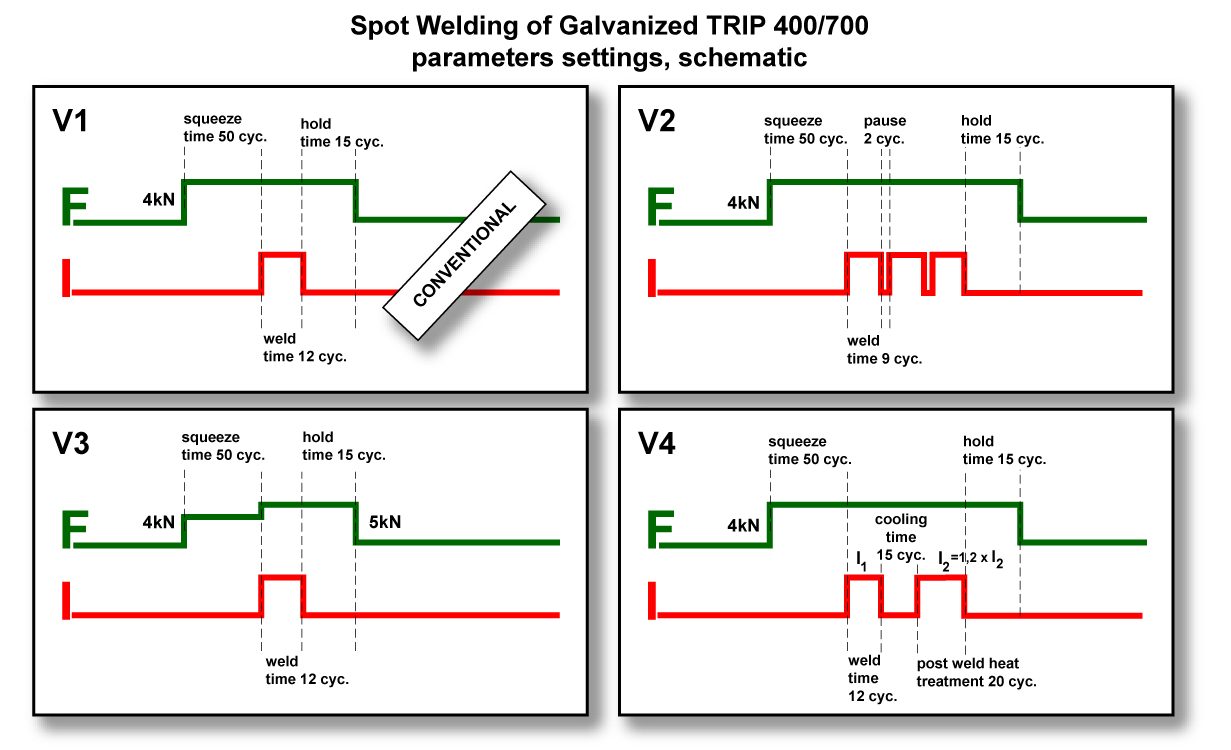

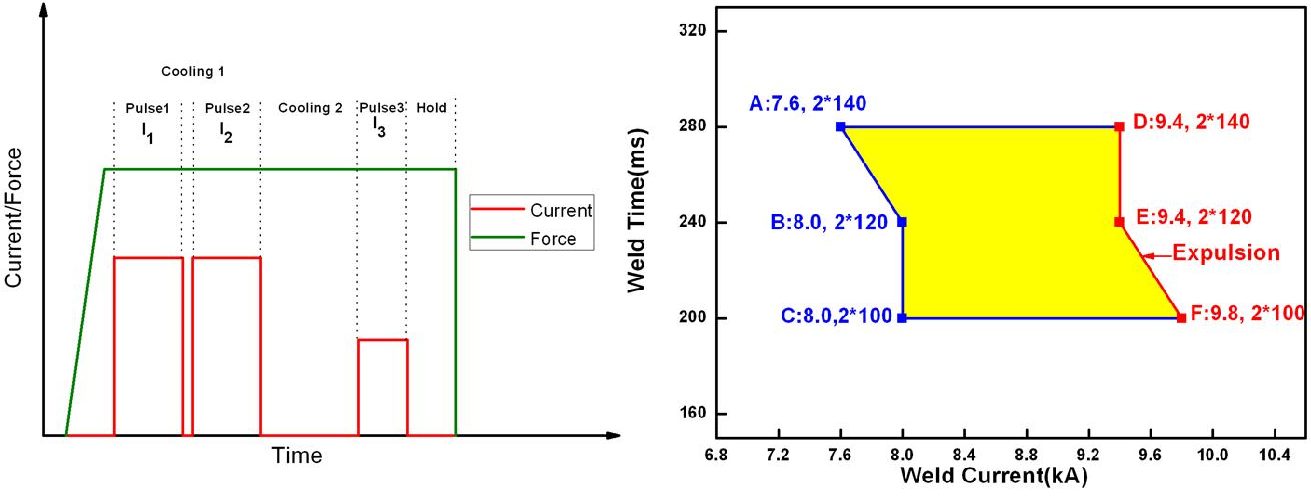

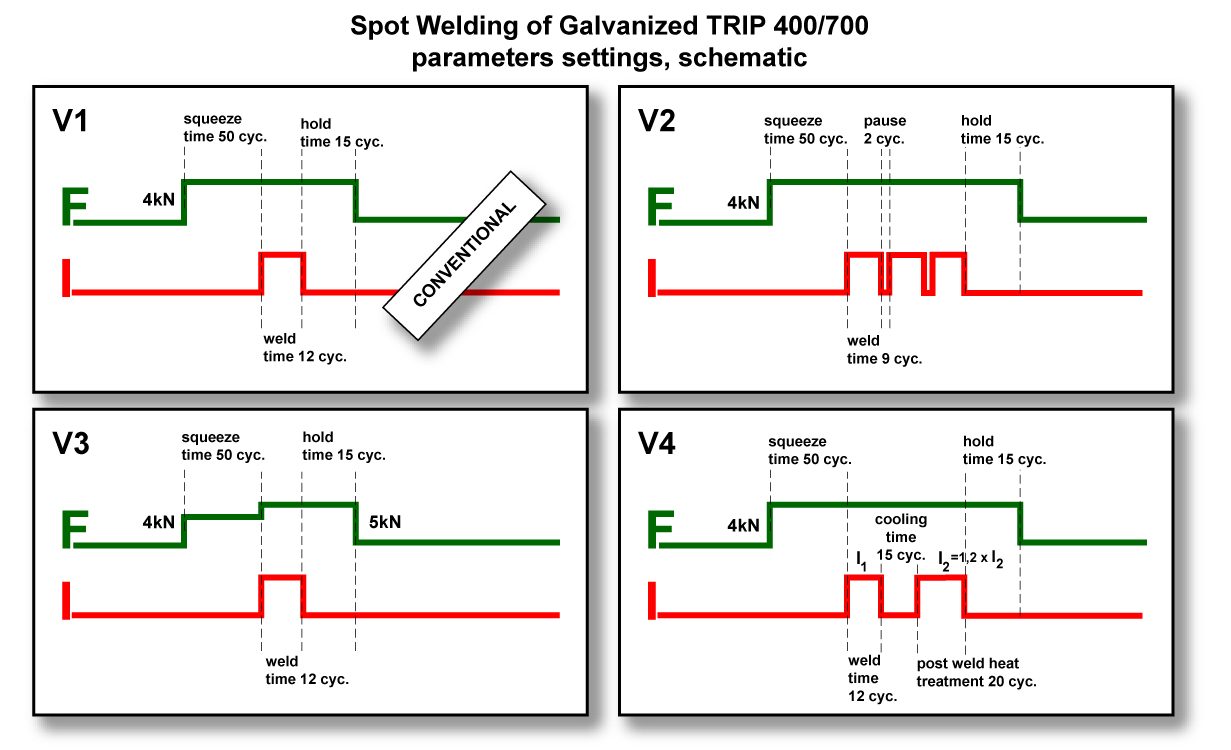

Weld schedules (Figure 5) with pulsed current profiles for AHSS can have weld-current ranges similar to mild steel. Even though there is no increased tendency for weld expulsion with AHSS avoiding weld expulsion is highly desirable with AHSS. Loss of nugget material can affect weld-nugget size and strength.

Figure 5: Schematics of optimized weld schedules for AHSS.B-1

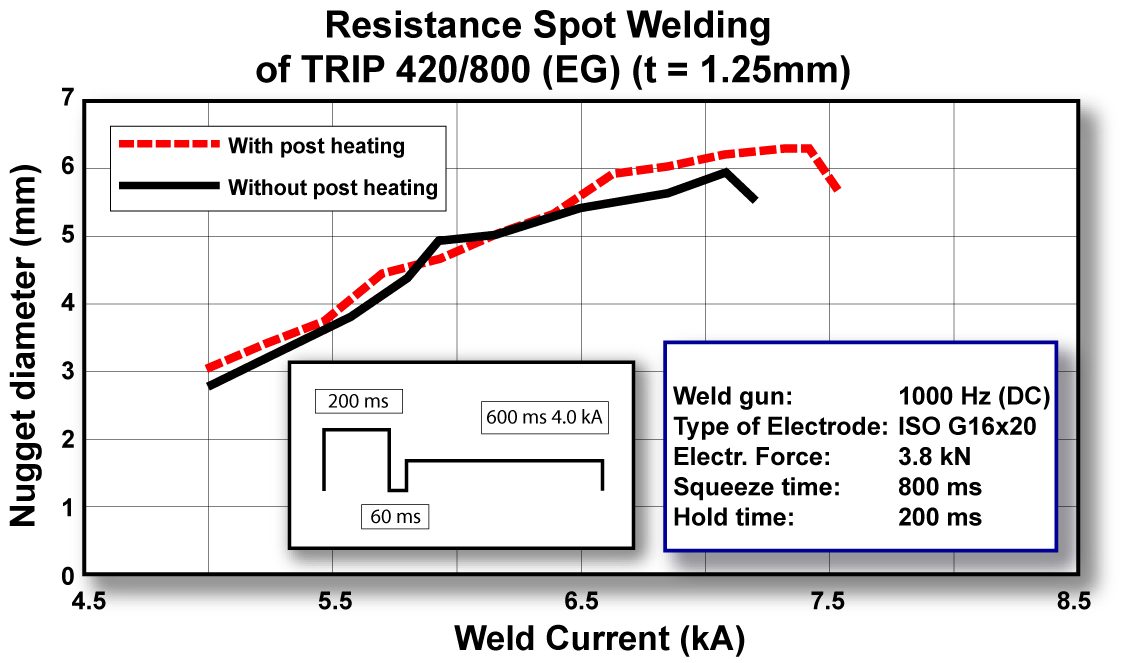

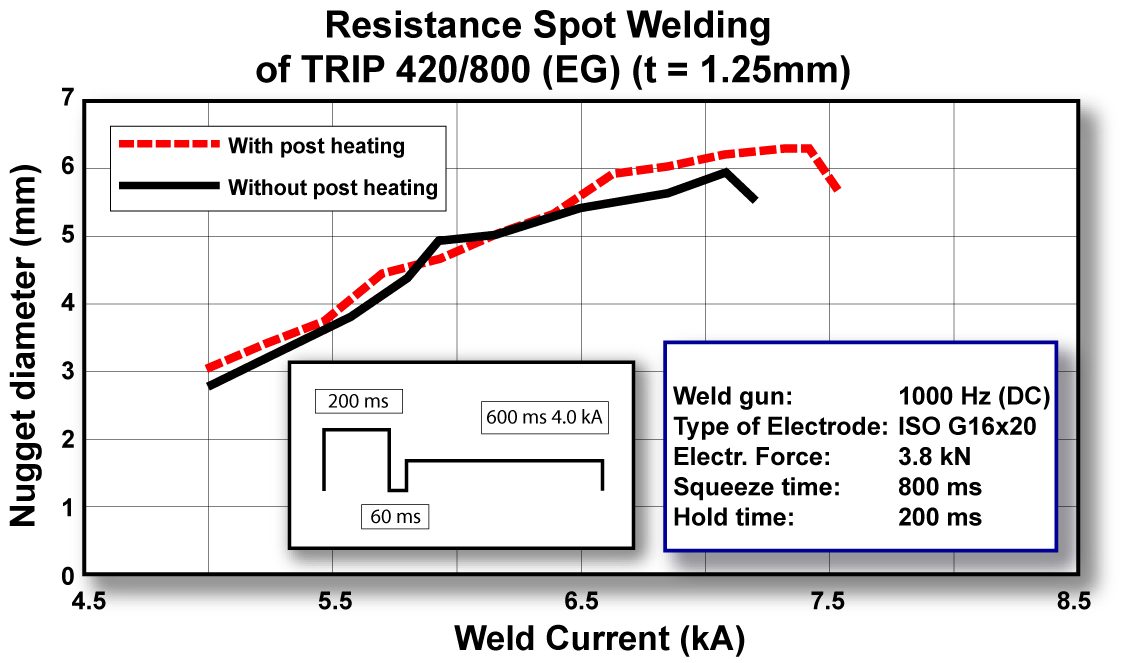

Post annealing (tempering pulse weld schedule) of TRIP steel may alter weld fracture mode and weld current range (Figure 6). However, since studies have shown that the occurrence of partial or IF fractures does not necessarily indicate poor weld quality, the use of pulsed current is not required to improve weld quality. Further, the effect of current pulsing on tensile and fatigue properties, as well as the electrode tip life, is not known. Therefore, users should perform their own evaluations regarding the suitability of such modified parameters.

Figure 6: Post annealing may enlarge weld current range.B-1

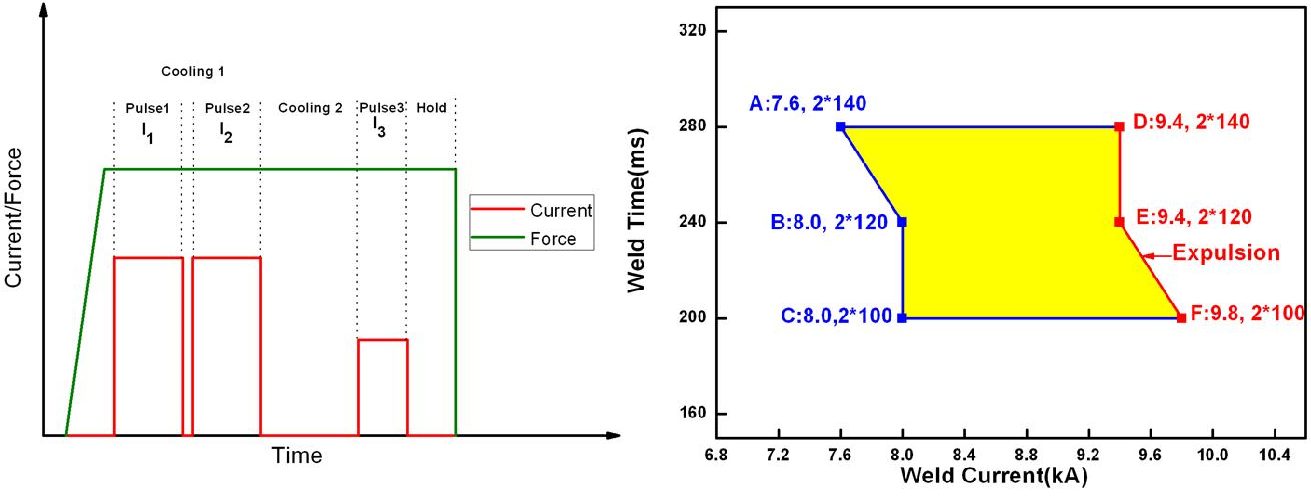

Additional work using Quench and Partition (Q&P) 980 showed less current required than conventional steels because it has higher electrical resistivity. Due to ultra-high base metal (BM) strength, it needs higher electrode force than conventional steels which have equivalent thickness. The weld lobe of 1.6-mm Q&P 980 is shown in Figure 7 with the pulsed weld time and force of 5.8 kN. The yellow zone of this figure shows the fracture mode of full button (FBF) when peel tested. Some pictures of these weld spots’ fracture mode are captured in Figure 8, for diameters of 6.0 to 7.7 mm.

Figure 7: Pulsed current profile and weld lobe of 1_6-mm Q&P 980.B-4

Figure 8: Fracture mode of weld spots in yellow zone.B-4

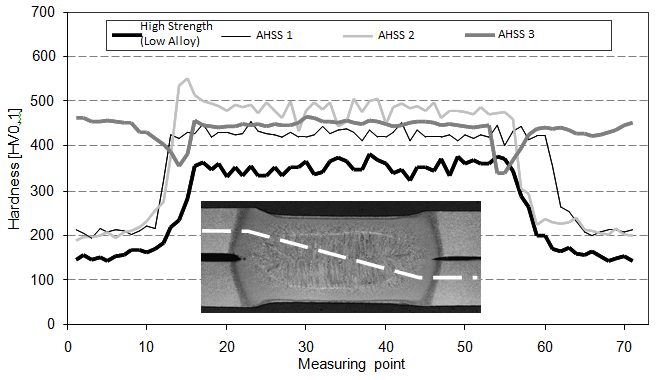

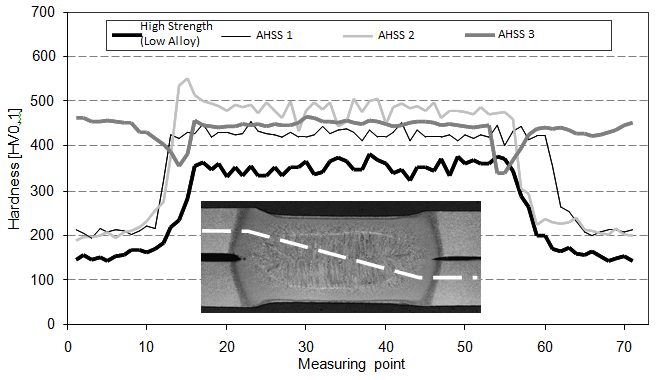

Hardness measurements and cross sections through the spot weld different zones can be identified as depicted in Figure 9. In a first step, the spot-welded joint can be subdivided into three zones: weld, Heat Affected Zone (HAZ), and BM. The weld is covered by the HAZ, where the melting temperature is not reached but high enough to change the microstructure. This region is dominated by inhomogeneous properties due to the different temperature and cooling gradients. Considering the hardness measurements of AHSS 3 sample, even a softening in the HAZ compared to the BM can be observed. Finally, the HAZ is surrounded by the BM, which does not show any local changes within the structure. These modifications of microstructure in the HAZ and weld are essential for the load-bearing capacity because the strength and ductility are drastically changed in comparison to the BM. Normally a high hardness is related to high strength and less ductility.

Figure 9: Hardness distribution through spot welds of various strength steels.P-7

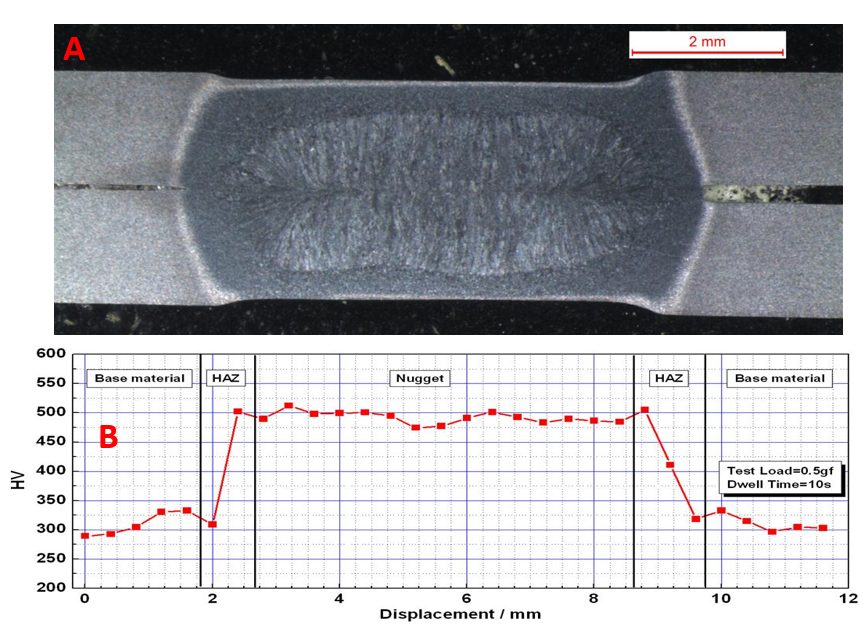

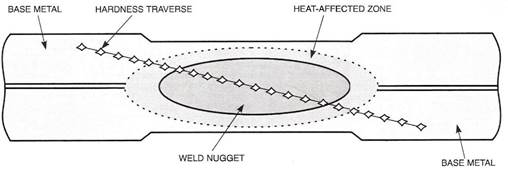

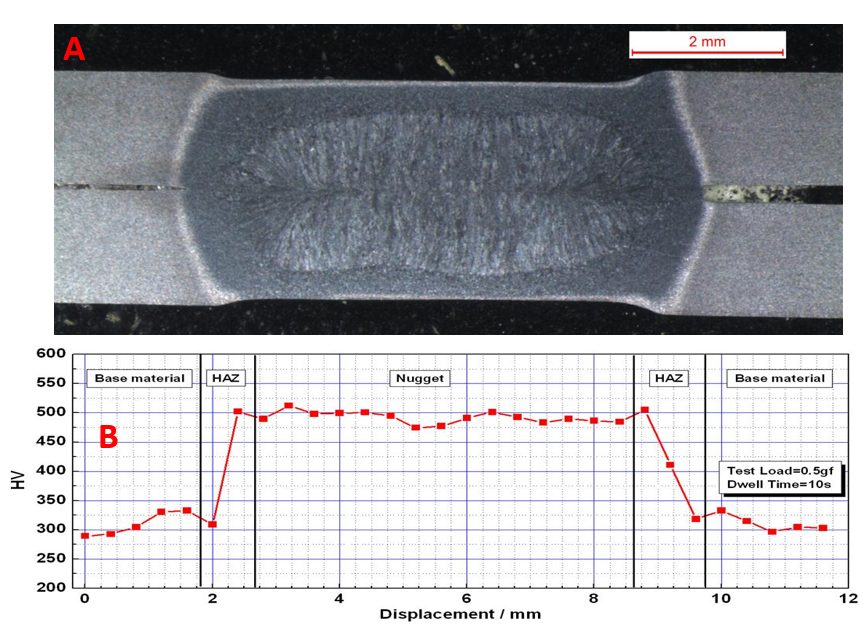

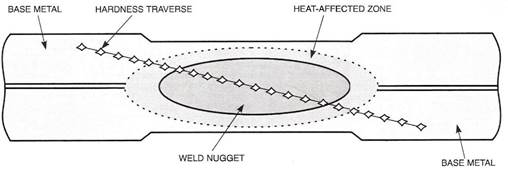

Weld spot micrograph and microhardness of 1.6-mm Q&P 980 is shown in Figure 10, in which no weld defects, such as cracks, shrinkage void, pore, no fusion, deep indentation, etc. were found. Hardness testing is typically performed as shown in Figure 11 (diagonal traverse across the weld from BM of top coupon to BM of bottom coupon) using a suitable instrument for micro-indentation hardness testing (Vickers or Knoop).

Figure 10: Weld spot micrograph and microhardness of 1.6-mm DP 980.B-4

Figure 11: Typical cross-sectioned weld and hardness traverse.A-13

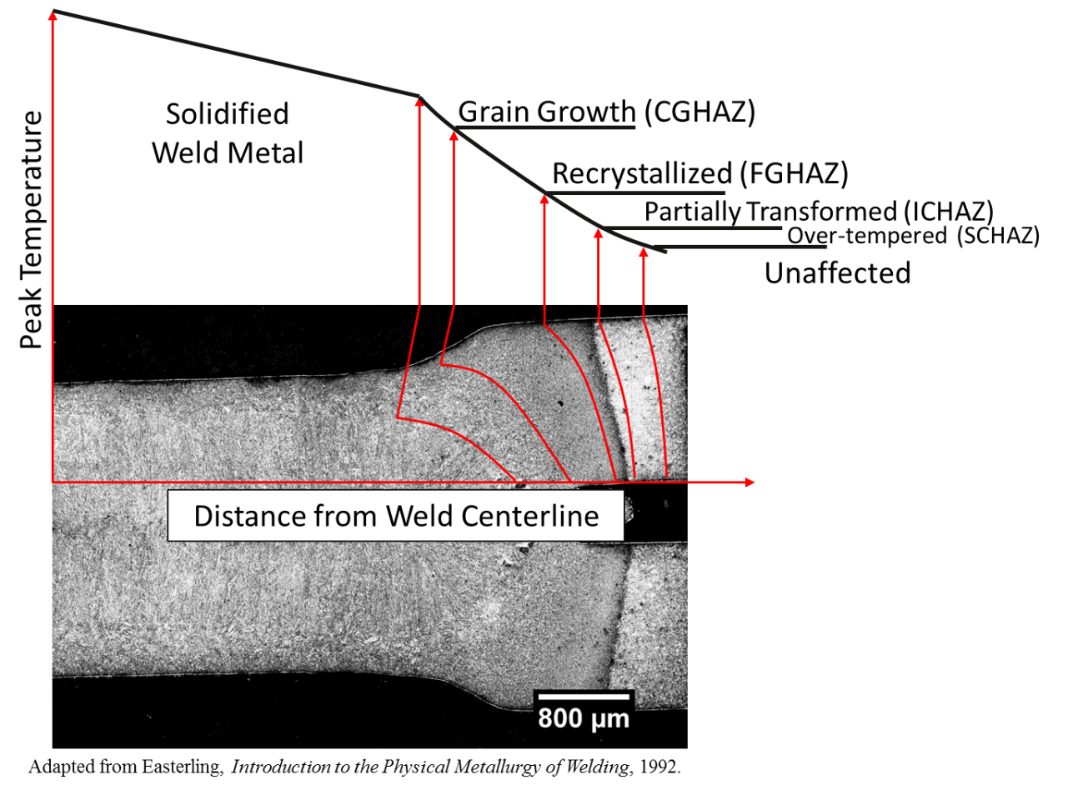

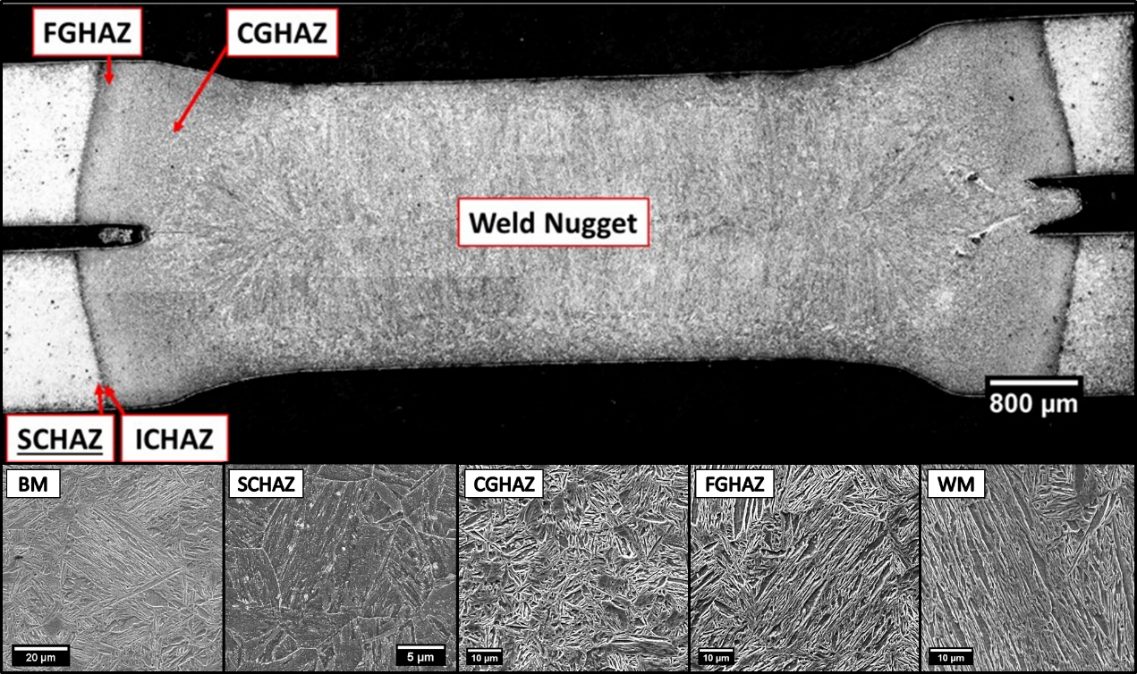

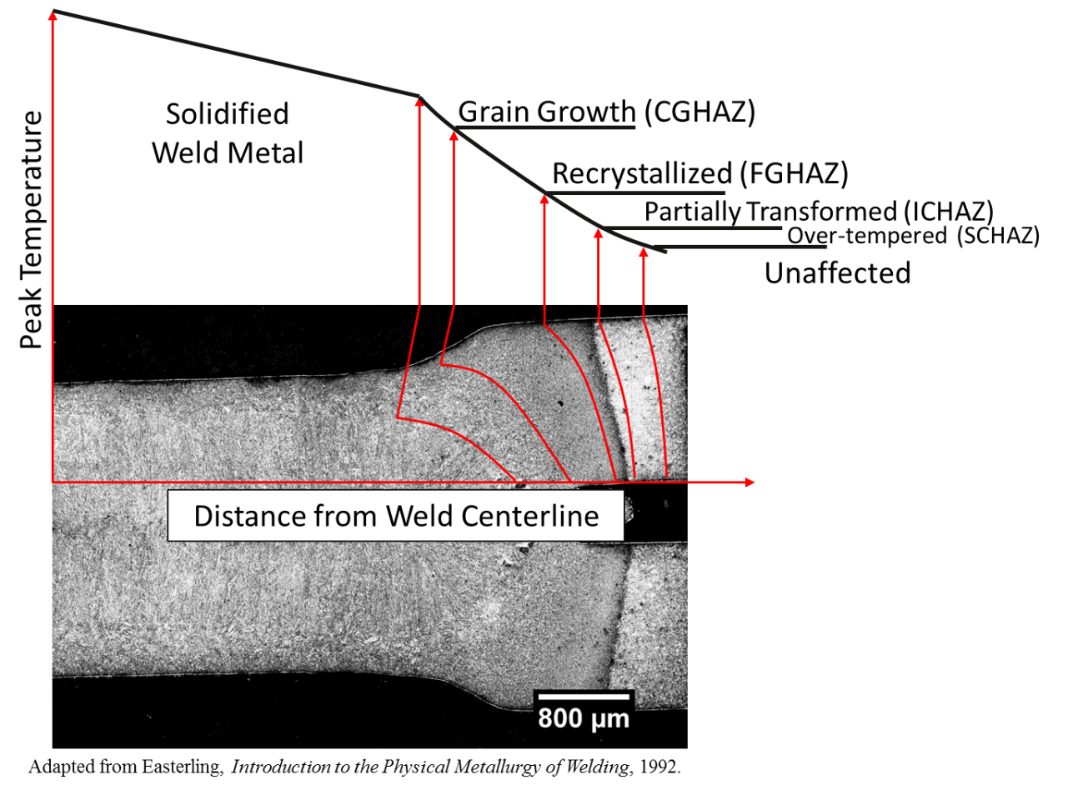

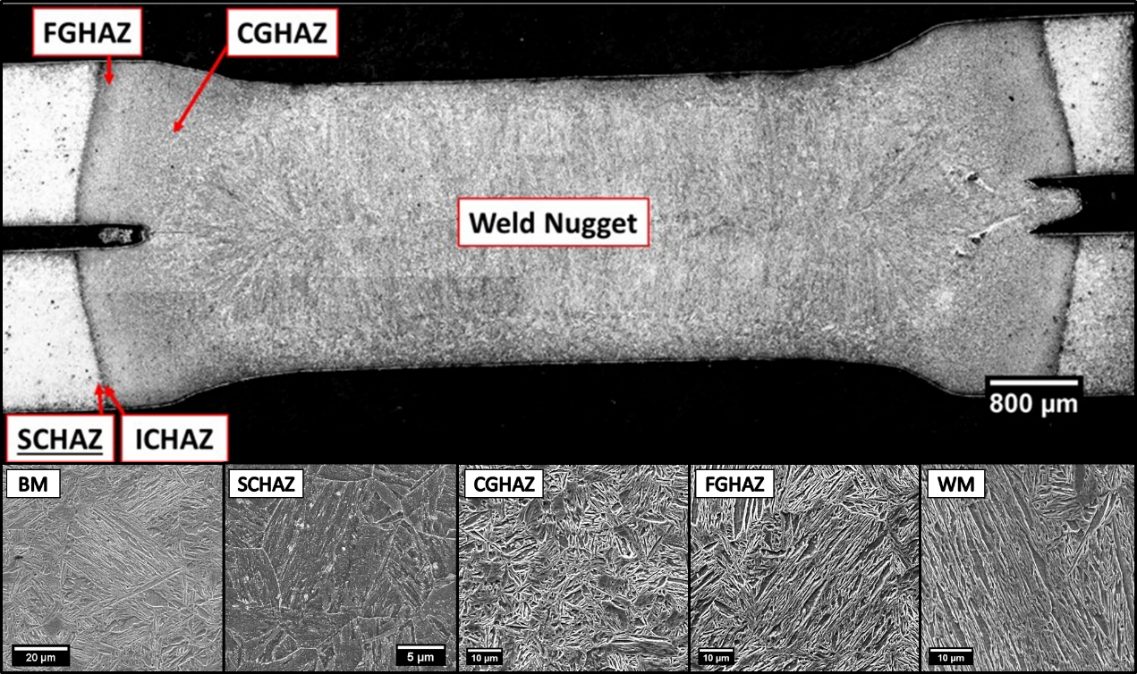

The different hardness values seen in a typical cross-sectioned weld depict different microstructural regions.P-8 Figure 12 shows the temperature distribution of a typical 2T weldment of hot stamped boron steel. At the solidified weld nugget, we see the highest temperatures and steadily decrease toward the unaffected base metal. The weld metal, coarse grain heat affected zone, fine grain heat affected zone, and unaffected base metal are made up of martensitic microstructure. The base metal has this microstructure due to the heat treatment (hot stamping) process. The weld metal, coarse grain heat affected zone, and fine grain heat affected zone are exposed to austenitizing temperature upon welding and are cooled rapidly reforming the martensite microstructure. The subcritical heat affected zone has a unique microstructure of over-tempered martensite. In this region, the peak temperature re below the Ac1, causing the base metal martensitic microstructure to decompose into ferrite and cementite. Micrographs of the different weld regions can be seen in Figure 13.

Figure 12: Temperature distribution of a typical 2T RSW of hot stamped boron steel.P-8

Figure 13: Different microstructures seen throughout the HAZ of a 2T hot stamped boron steel joint.P-8

homepage-featured-top, main-blog

In this edition of AHSS Insights, George Coates and Menachem Kimchi get back to basics with important fundamentals in forming and joining AHSS.

As the global steel industry continues its development of Advanced High-Strength Steels (AHSS), including 3rd Gen products with enhanced formability, we’re reminded that successful application is still dependent on the fundamentals, both in forming and joining. In this blog article, we address some of those forming considerations, as well as highlighting common joining issues in manufacturing.

Forming Considerations

The somewhat lower formability of AHSS compared to mild steels can almost always be compensated for by modifying the design of the component and optimizing blank shape and the forming process.

In stamping plants, we’ve observed inconsistent practices in die set-up and maintenance, surface treatments and lubrication application. Some of these inconsistencies can be addressed through education, via training programs on AHSS Application Guidelines. These Guidelines share best practices and lessons learned to inform new users on different behaviors of specific AHSS products, and the necessary modifications to assist their application success. In addition to new practices, we’ve learned that applying process control fundamentals become more critical as one transitions from mild steels to AHSS, because the forming windows are smaller and less forgiving, meaning these processes don’t tolerate variation well. If your present die shop is reflective of housekeeping issues, such as oil and die scrap on the floor or die beds, you are a candidate for a shop floor renovation or you will struggle forming AHSS products.

Each stamping operation combines three main elements to achieve a part meeting its desired functional requirements:

There is good news, in that our industry is responding with new products and services to improve manufacturing performance and save costs.

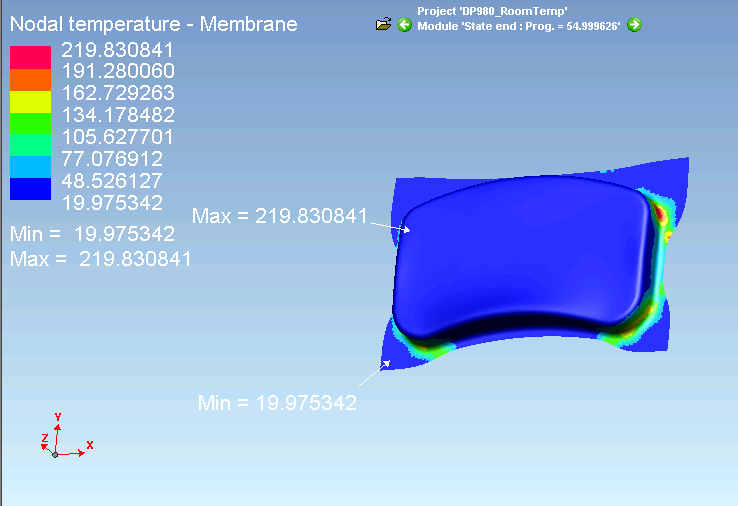

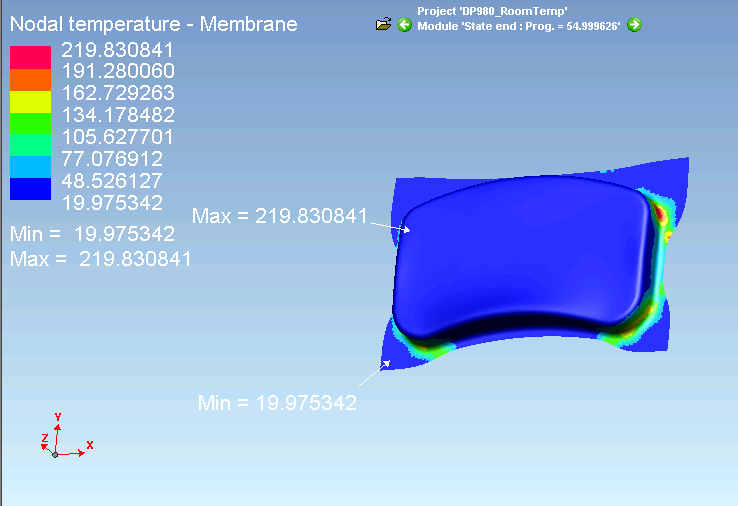

As an example, lubrication application is often overlooked, and old systems may be ineffective. In the forming of AHSS, part temperatures can become excessive, and break down lubricant performance. Figure 1 shows an example of part temperatures from an Ohio State University study conducted with DP 980 steels.O-1

Figure 1: Example Temperature distribution for DP 980 Steel.O-1

Stampers often respond by “flooding” the process with extra lubricant, thinking this will solve their problem. Instead, lubricant viscosity and high temperature stability are the most important considerations in the lubricant selection, and new types exist to meet these challenges. Also, today there are new lubrication controllers that can finely control and disperse wet lubricants evenly across the steel strip, or in very specific locations, if forming requirements are localized. These enable better performance while minimizing lubricant waste (saving cost), a win-win for the pressroom.

Similarly, AHSS places higher demands on tool steels used in forming and cutting operations. In forming applications, galling, adhesive wear and plastic deformation are the most common failure mechanisms. Surface treatments such as PVD, CVD and TD coatings applied to the forming tool are effective at preventing galling. Selection of the tool steel and coating process used for forming AHSS will largely depend on the:

- Strength and thickness of the AHSS product,

- Steel coating,

- Complexity of the forming process, and

- Number of parts to be produced.

New die materials such as “enhanced D2” are available from many suppliers. These improve the balance between toughness, hardness and wear resistance for longer life. These materials can be thru-hardened, and thus become an excellent base material for PVD or secondary surface treatments necessary in the AHSS processing. And new tool steels have been developed specifically for hot forming applications.

Joining Considerations

In high-volume production different Resistance Spot Welding (RSW) process parameters can be used depending on the application and the specifications applied. Assuming you chose the appropriate welding parameters that allows for a large process window, manufacturing variables may ruin your operation as they strongly effect the RSW weld quality and performance.

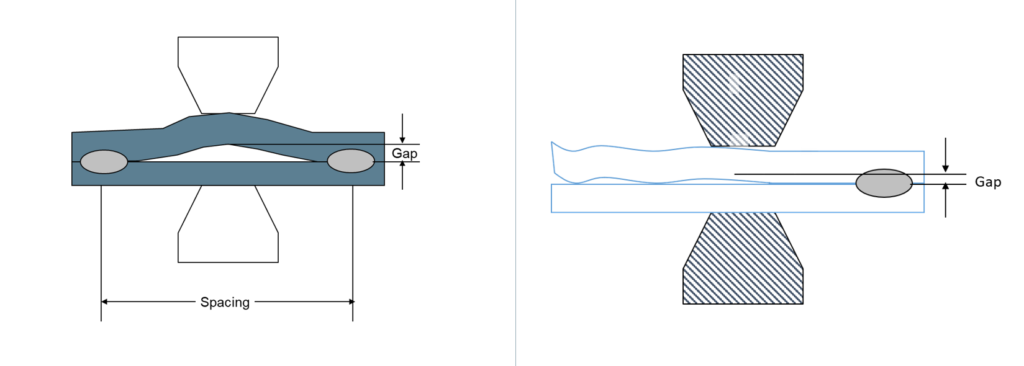

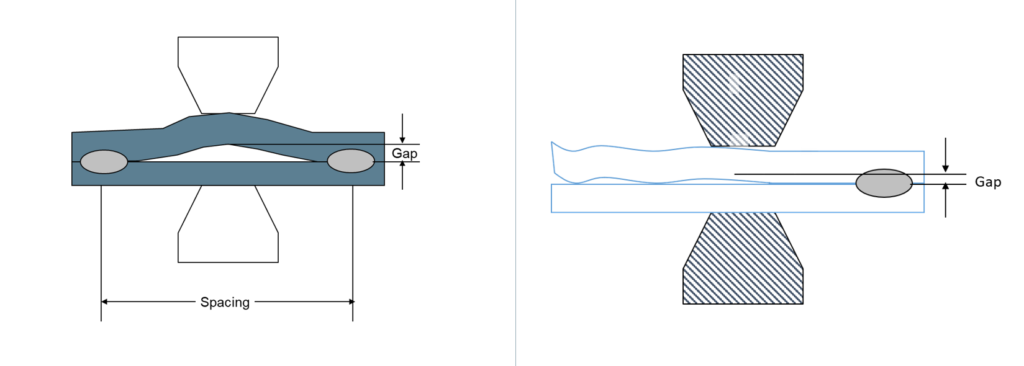

Material fit-up

One of the great advantages of the RSW process is the action of clamping the material together via the electrode force applied during the process. However due to the pre-welding condition/processing such as the stamping operation, this fit-up issue, as shown in Figure 2, can be very significant especially in welding an AHSS product. In this case the effective required force specified during the process setup for the application is significantly reduced and can result in an unacceptable weld, over-heating, and severe metal expulsion. If the steels are coated, higher probability for Liquid Metal Embrittlement (LME) cracking is possible.

Figure 2: Examples of Pre-Welding Condition/Processing Fit-Up Issues.

For welding AHSS, higher forces are generally required as a large part of the force is being used to force the parts together in addition to the force required for welding. Also, welding parameters may be set for pre-heating with lower current pulses or current up-slope to soften the material for easier material forming and to close the gap.

Electrodes Misalignment

During machine set up, the RSW electrodes need to be carefully aligned as shown in Figure 3A. However, in many production applications, electrode misalignment is a common problem.

Electrode misalignment in the configurations shown in Figure 3B may be detrimental to weld quality of any RSW application. Of course, the electrode misalignment shown in this figure is exaggerated but the point is that it happens frequently on manufacturing welding lines.

In these cases, the intendent contact between the electrodes is not achieved and thus the current density and the force density (pressure) required for producing an acceptable weld cannot be achieved. With such conditions, overheating, expulsion, sub-size welds and extensive electrode wear will result. Again, if coated steels are involved, the probability for LME cracking is higher.

Note also that following specifications or recommendations for water cooling the electrode is always important for process stability and extending electrode life.

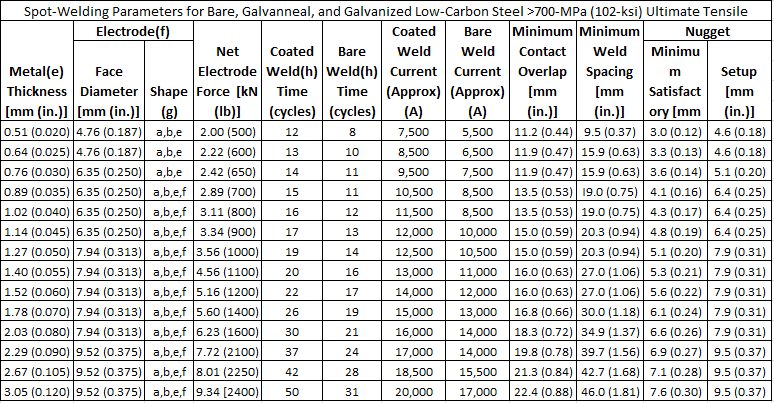

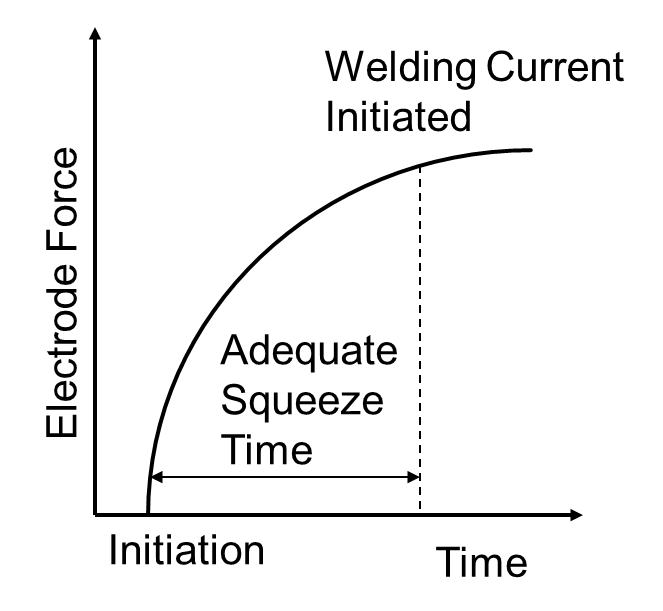

Figure 4: Sequence of Squeeze Time and Welding Current Initiation.

Squeeze Time

The squeeze time is the time required for the force to reach the level needed for the specific application. Welding current should be applied only after reaching this force, as indicated in Figure 4. All RSW controllers enable the easy control of squeeze time, just as with the weld time, for example. In many production operations, a squeeze time is used that is too low due to lack of understanding of its function. If squeeze time is too low, high variability in weld quality in addition to severe expulsion will be the result.

The squeeze time required for an application depends on the machine type and characteristics (not an actual welding parameter such as weld time or welding current for example).

Some of the more modern force gauges have the capability to produce the curve shown in the Figure so adequate squeeze time will be used. If you do not know what the required squeeze time for your machine/application is, it is recommended to use a longer time.

For more on these topics, browse the Forming and Joining menus of these Guidelines.