Localized Fracture vs. Generalized Fracture in Auto Stamping

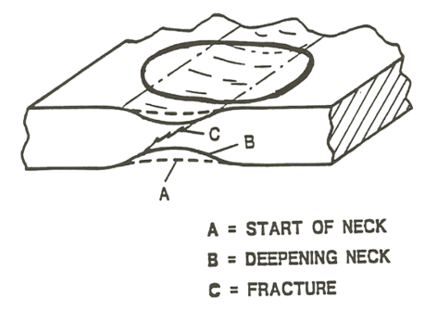

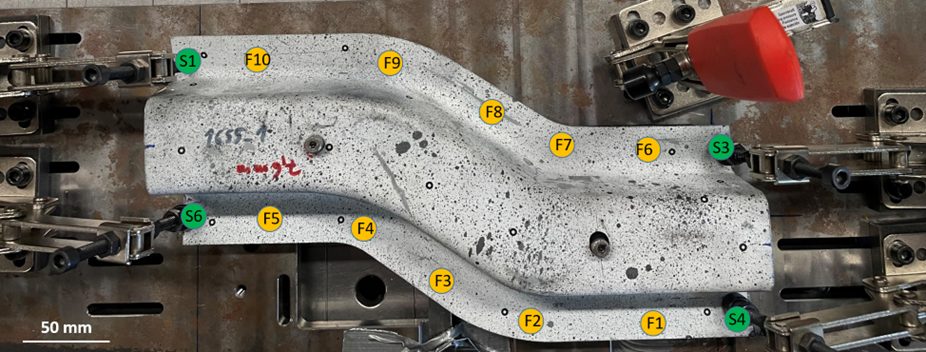

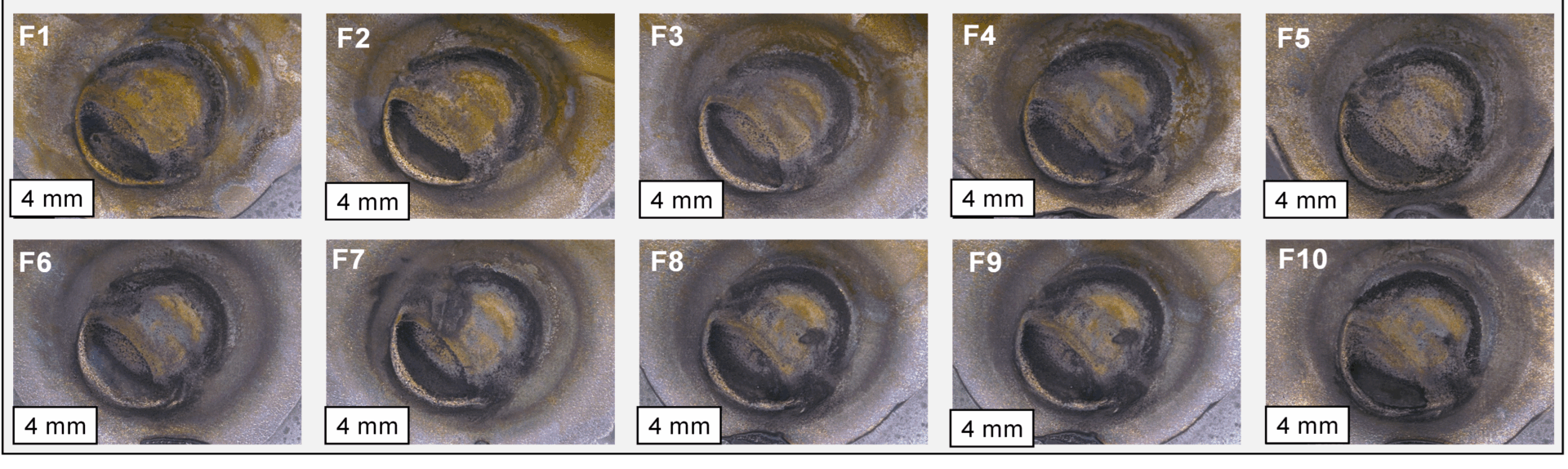

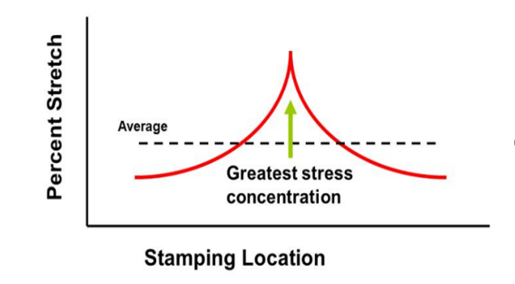

To understand the difference between localized and global fractures, you must first understand strain gradients (see the article in our blog, AHSS Strain Hardening and Gradients). Gradients can result in highly concentrated strains (peak strain condition) that typically occurs in an embossment or character line where the deformation mode is in plane strain. Peak strains can develop rapidly in a very localized area (Figure 1). Under additional loads, this can result in the onset of localized necking, which means the material has reached its tensile strength and will fail at its weakest point or highest strain. When a slight increase in strain is applied, the material will fracture, sometimes at deformation levels less than predicted. This condition can be found in AHSS products, where multiple phases exist within the steel’s microstructure, each with different properties. A global fracture also typically occurs in plane strain, but more commonly down a sidewall or other area with more moderate geometry complexity.

Peak (concentrated) strains are susceptible to localized fractures when even slight variation exists in the forming process. Examples of variation include lubrication pattern and volume, die recipe including blank position, press conditions, and material characteristics.

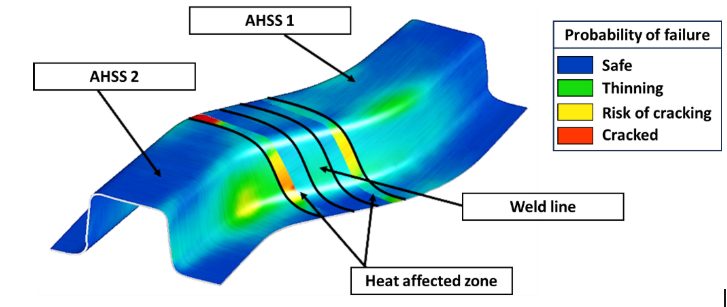

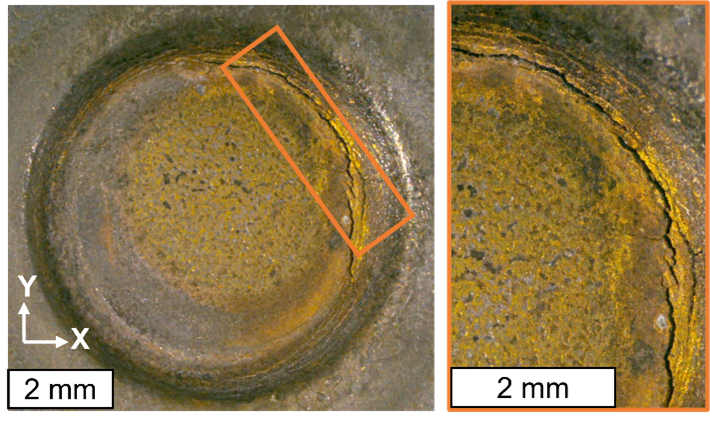

A localized neck and/or fracture (Figure 2) reduces the sheet metal’s thickness, reducing part strength, and compromising functional performance such as fatigue life, crash worthiness, and stamping stiffness. There are a number of formability analysis tools that can differentiate localized and global fractures and enable die makers to implement die and process improvements that minimize fracture susceptibility. The result is a more robust stamping process.

Process control is critical; die recipe discipline is needed to minimize tinkering with die recipe, press settings, and lubrication settings. Mechanical properties of the sheet metal should be tracked to identify trends or variations in the material, and establish the material forming window. Typical mechanical properties that are available from the steel supplier are yield strength, tensile strength, n-value, total and uniformed elongation, and sheet thickness. Additional properties that should be determined include hole expansion and deep cup draw ratios. Failure to identify strain levels, process variables and variation will lead to a reactionary approach to controlling the output. This will lead to an increase in scrap, die-related downtime, and of course, costs.

Contributions made by Phoenix Group.