This article explores the challenges of liquid metal embrittlement (LME) in resistance spot welding (RSW) of automotive components, particularly focusing on a component-scale S-Rail made from advanced high-strength steel (AHSS). The study aims to identify the occurrence of LME during the welding process and to propose effective strategies for its mitigation. This article is an excerpt from the “LME component study” conducted by WorldAutoSteel. The full study can be downloaded here.

Experimental and Simulative Setup

The experiments utilized an electrogalvanized RA1180 AHSS joined to hot-dip galvanized mild steel. Two stack-up configurations were tested: similar (both sheets made of RA1180) and dissimilar (RA1180 on top of mild steel). The resistance spot welding process was monitored using sensors to record current, voltage, and force. Different welding parameters, such as hold time and electrode geometry, were varied to observe their effects on LME.

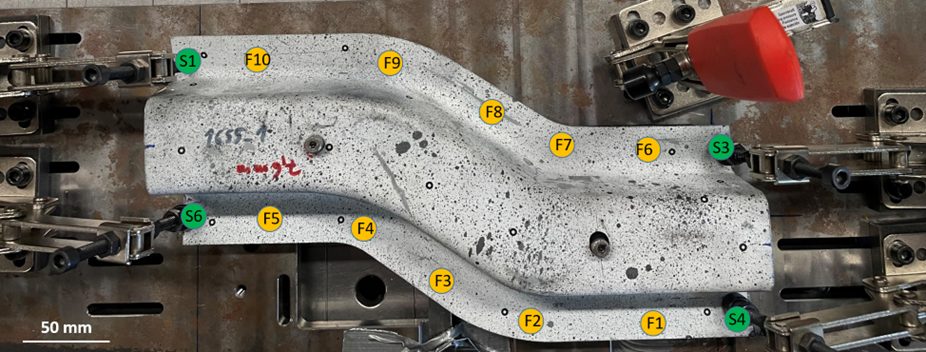

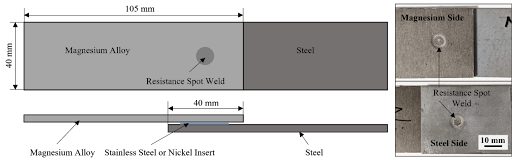

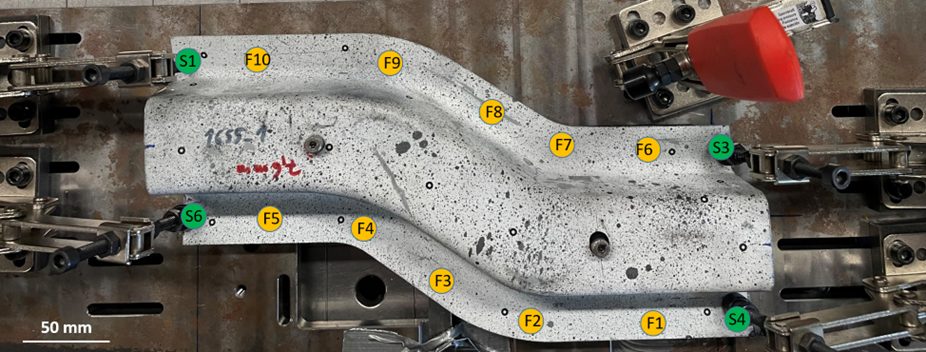

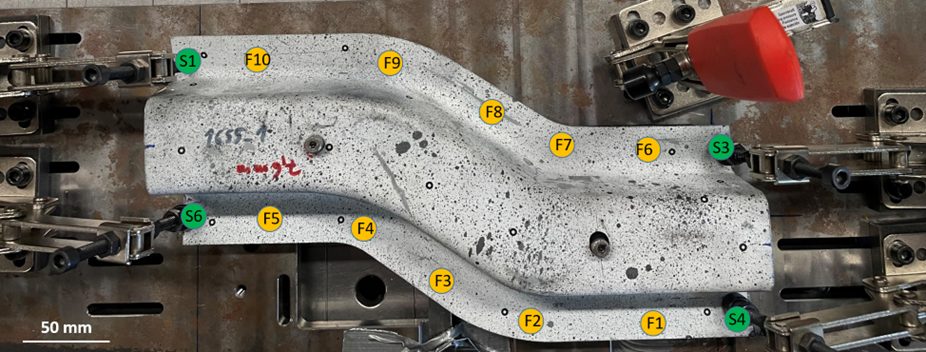

Figure 1: Top-view of the S-Rail component during welding. The clamping points S1-S4 as well as the welding points F1-F10 are highlighted.

A simulation-based risk criterion for LME was established based on local stresses in the components. Both experimental and numerical analyses were conducted to assess the influence of various parameters on LME formation. Specifically, the study evaluated how springback, a phenomenon occurring during deep drawing, affects LME risk. Correct clamping can effectively suppress springback, consequently reducing LME occurrences.

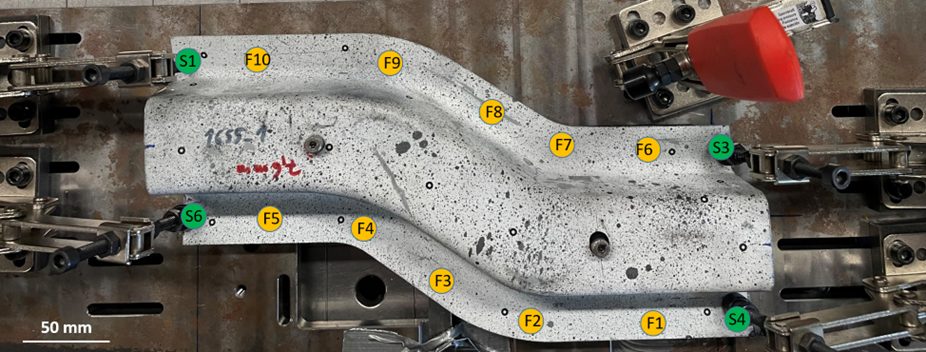

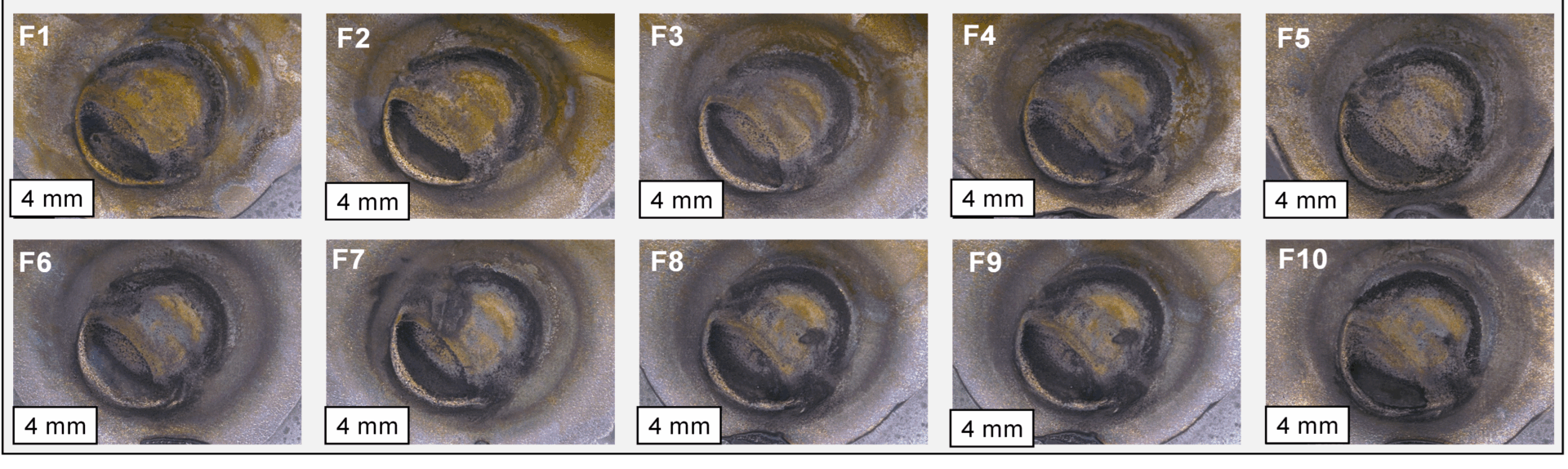

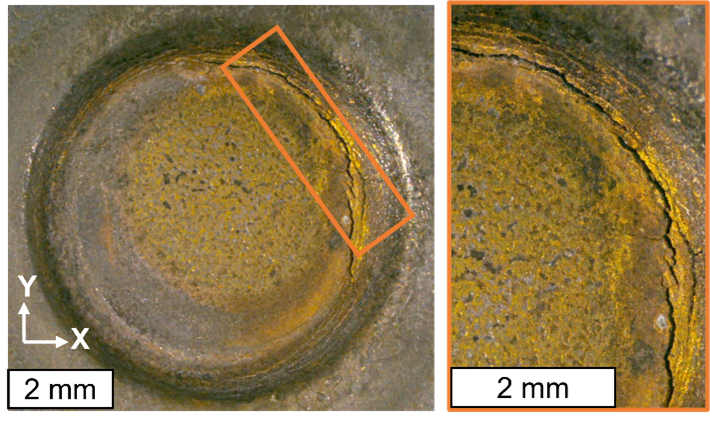

Figure 2: Experimentally observed cracks with 5° tilted electrodes and doubled welding time of 760 ms.

Findings

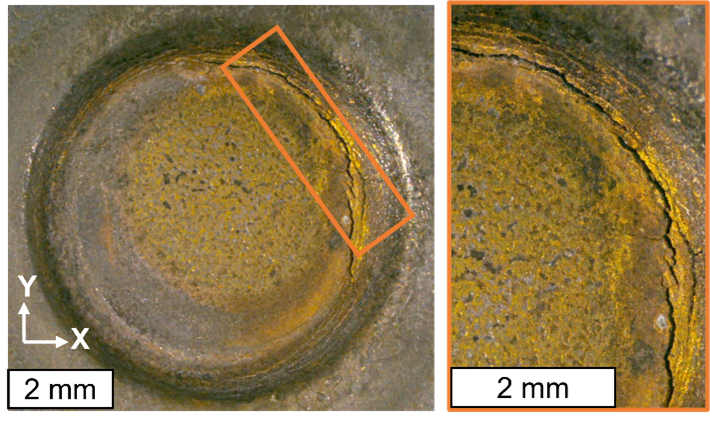

- Influence of Springback: Springback contributed to LME formation. When clamping was employed to counteract springback, LME was effectively eliminated from the welded samples.

- Electrode Geometry and Hold Time: Adjustments to the electrode geometry and increasing hold time after welding further mitigated LME risks. Specifically, larger electrode tip diameters and longer hold times reduced the likelihood of cracks.

- Material Stack-up Effects: The experiments indicated that the configuration of the material stack-up influenced LME occurrences. Only stack-ups with thick joining partners showed occurrence of LME in the trials.

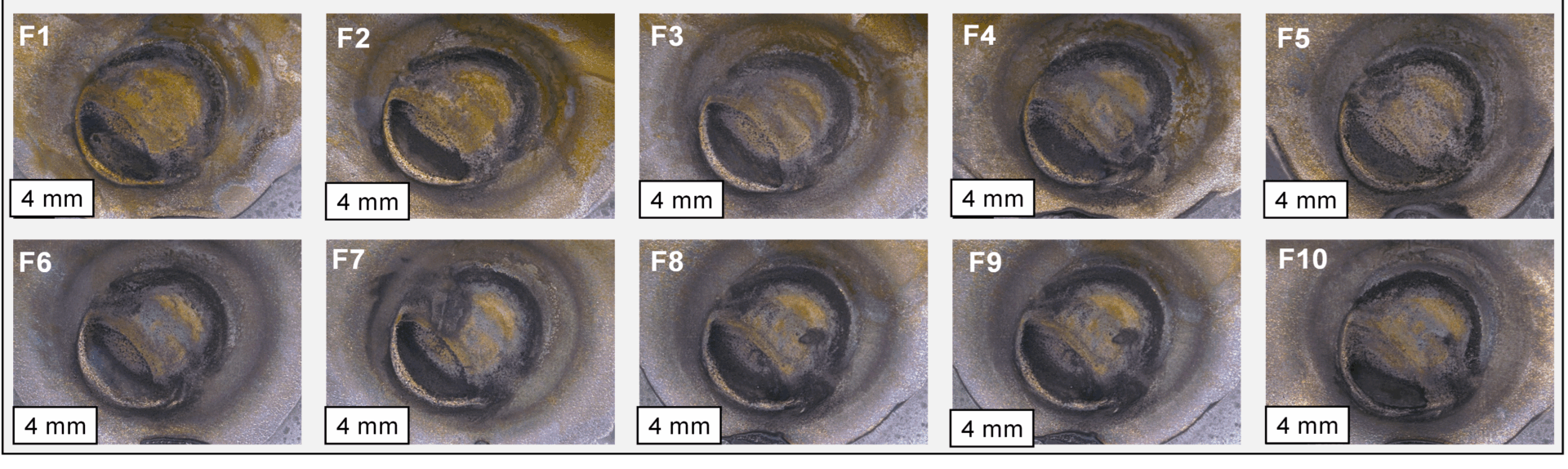

Figure 3: All 10 resistance spot welds on the S-rail are crack-free after optimizing either springback, electrode working plane diameter or post-weld hold time

Simulation Results

Finite element simulations were used to evaluate the risk of LME by analyzing local stresses and temperature distributions during welding. The results showed that the springback-affected samples presented a higher LME risk compared to idealized, straightened models. This finding aligns with experimental observations that cracks occurred where excessive springback influenced the welding process. Even in the case of springback, LME could be effectively prevented by using electrode caps with larger working planes as well as slightly extending the hold time after welding.

The developed simulation approach allows comparing the LME conditions for different welding setups and can therefore optimize the LME occurrence for geometry, material and welding conditions.

Conclusion

Effective mitigation strategies, such as clamping to suppress springback and adjustments in welding parameters, can prevent LME on a component-scale. It can also be highlighted that today’s AHSS grades are far less sensitive to LME by-default so that few RSW joints in a whole body-in-white are at all susceptible for cracking: To produce cracks for this study, welding parameters with increased energy input had to be used; no LME was observed under “standard” industrial conditions.

A dynamic tensile test was conducted to evaluate the mechanical properties of spot welds under automotive collision conditions. The actual tensile shear strengths of steel sheets with nominal tensile strengths ranging from 270 MPa to 780 MPa were investigated.

Visit our page on high strain rate testing to learn more about the equipment and testing challenges.

Test Method

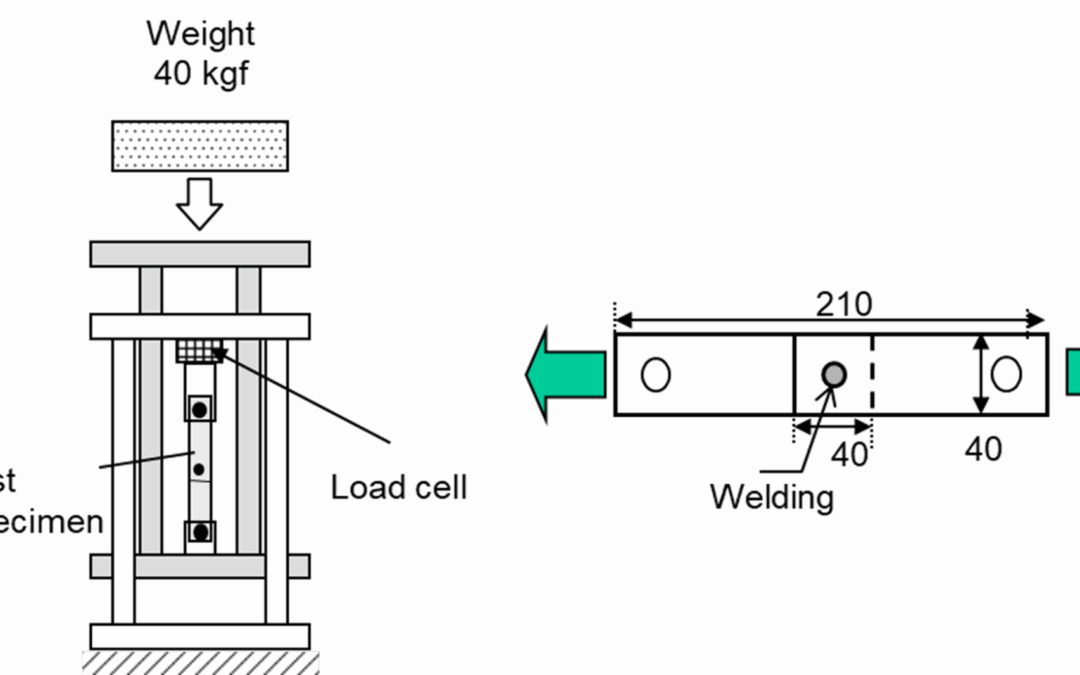

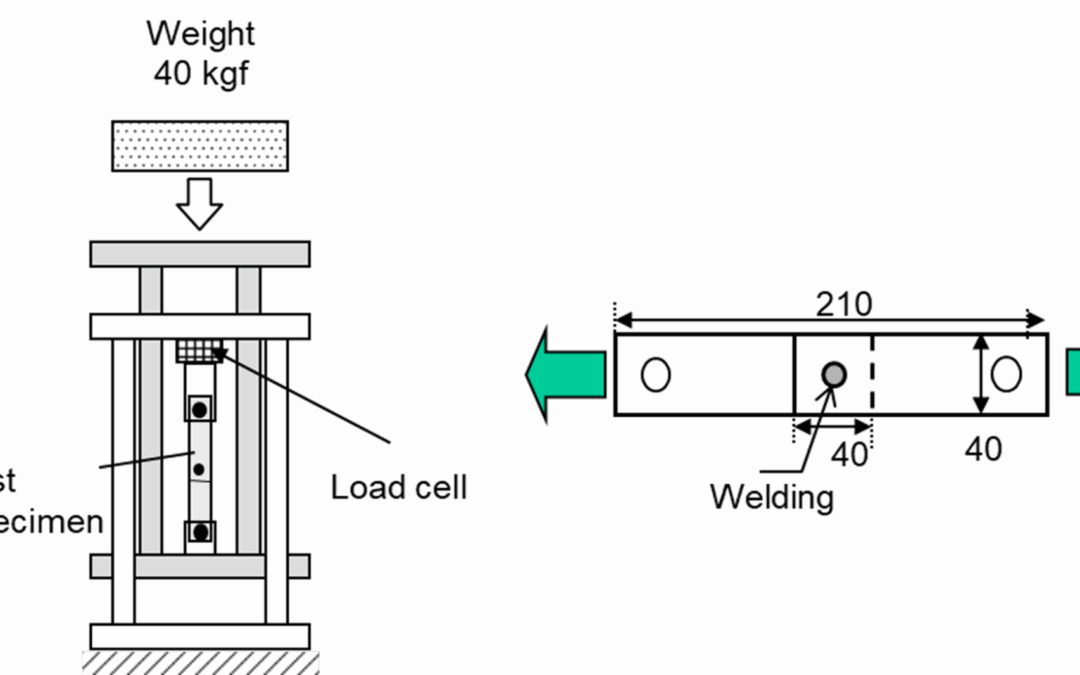

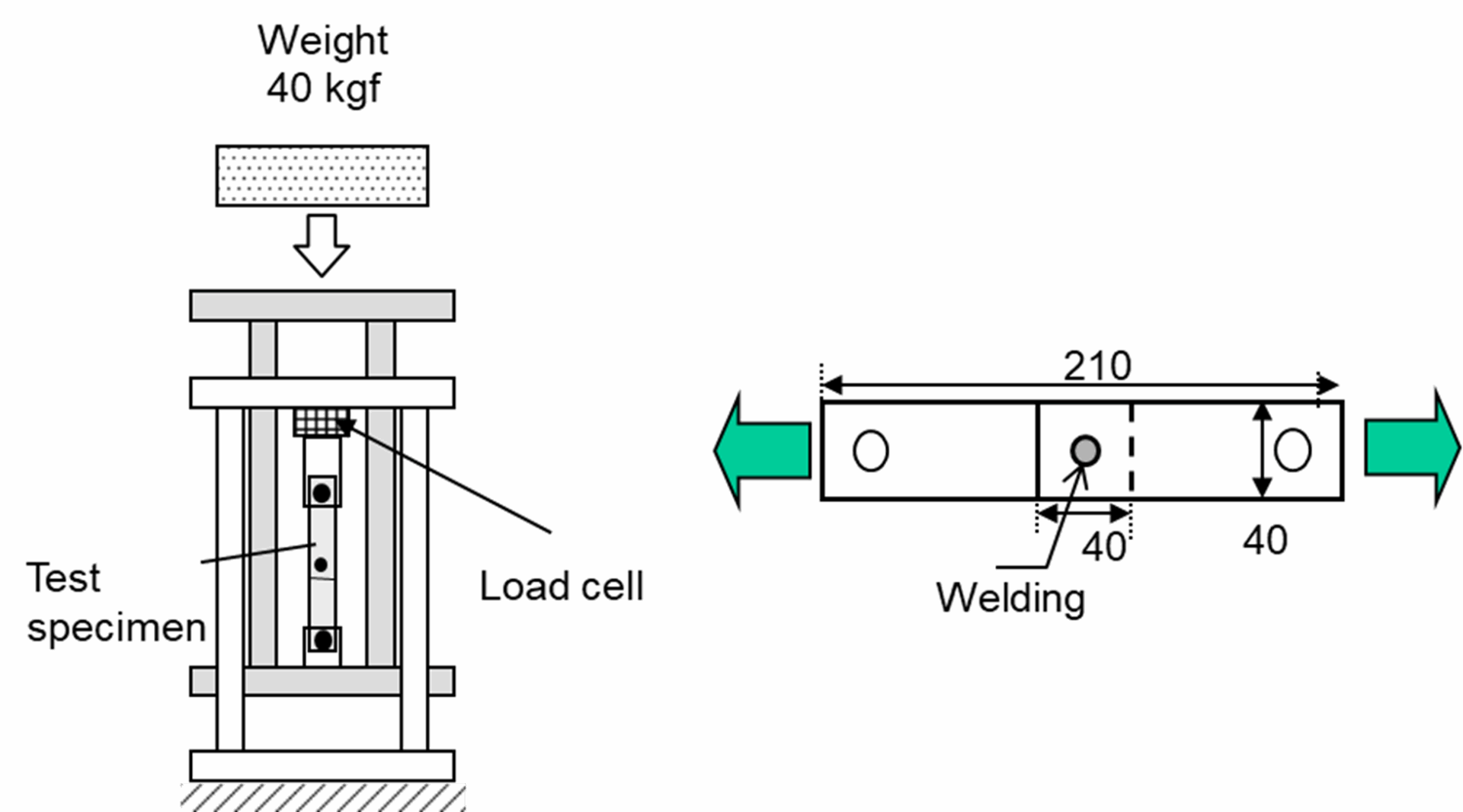

Figure 1 presents the dynamic tensile test machine and illustrates a schematic diagram of the tensile shear test specimen. A 1.6 mm thick steel sheet was placed on top of the tensile shear test specimen and spot welded, with nugget diameters of 5.5√t (7.0 mm) used for both. In the dynamic tensile test, a cone was dropped at high speed onto the specimen to apply a tensile load and determine the breaking point. The tensile speed was adjusted by varying the drop height of the cone, with a maximum speed of 2.4 m/s. For comparison, a static tensile test was conducted at a tensile speed of 1.6 × 10-4 m/s.

Figure 1: Dynamic tensile shear test equipment (left) and test specimen (right)

Results

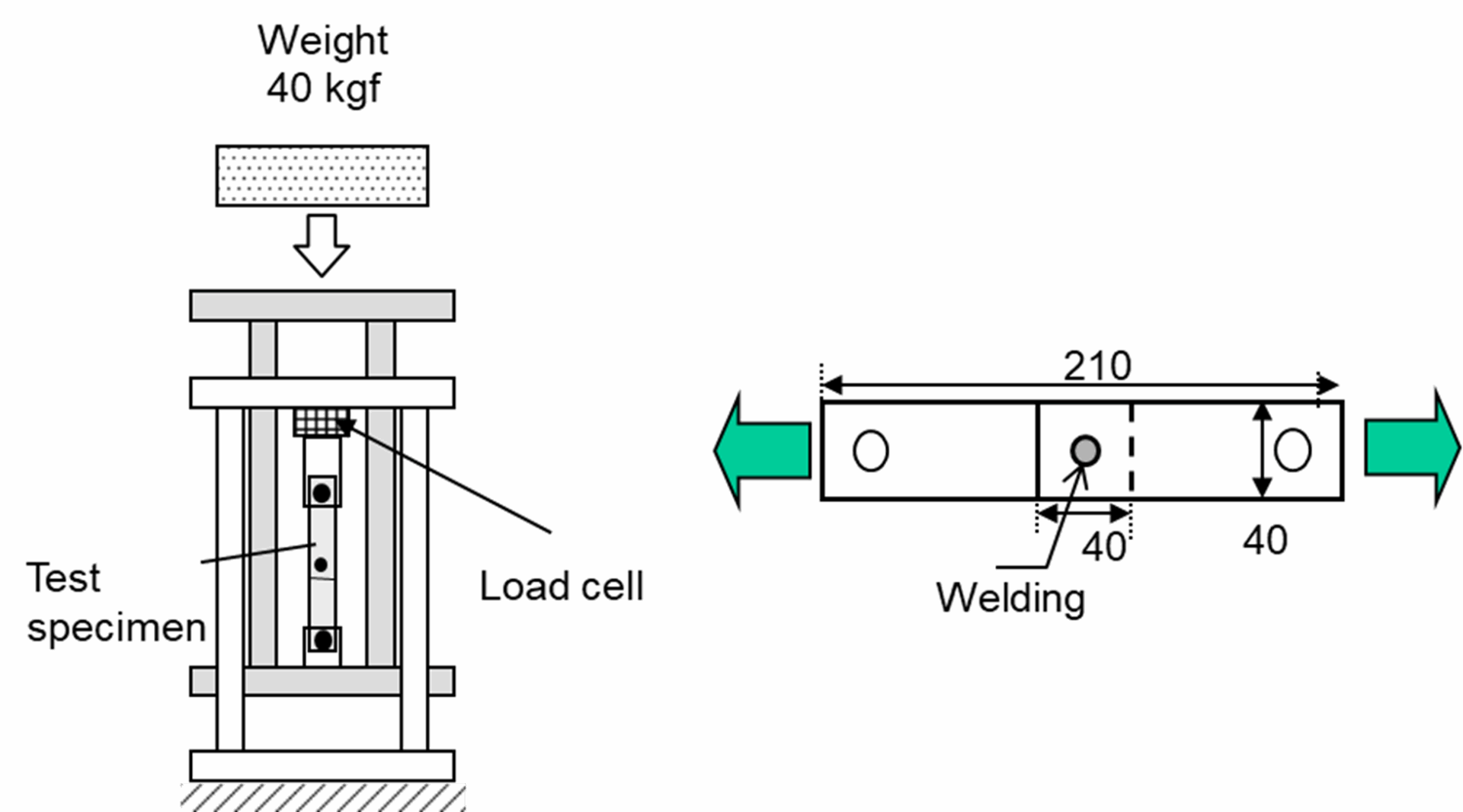

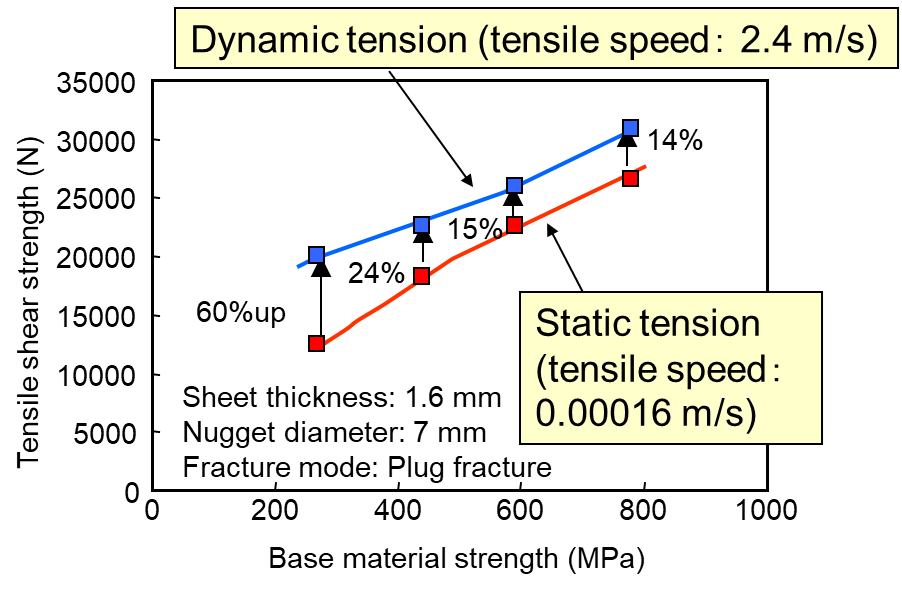

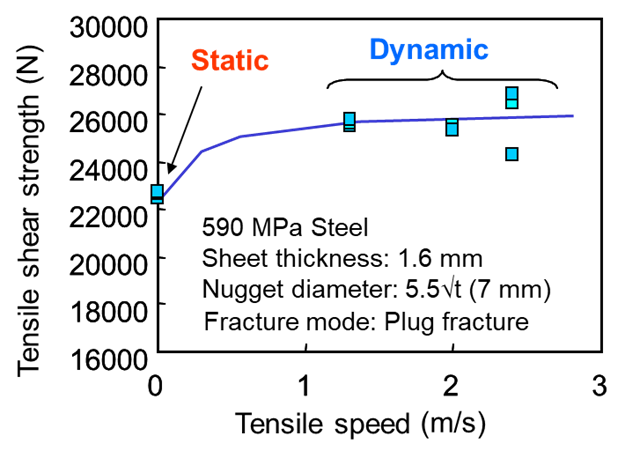

Figure 2 shows the relationship between tensile shear strength and tensile speed for the steel sheet with a rated tensile strength of 590 MPa. Tensile shear strength tended to increase with tensile speed, with values of approximately 22 kN and 25.5 kN under static and dynamic loading conditions, respectively. All specimens exhibited plug fracture as the failure mode

Figure 2: Relationship between tensile shear strength and tensile speed (steel sheet with a rated tensile strength of 590 MPa)

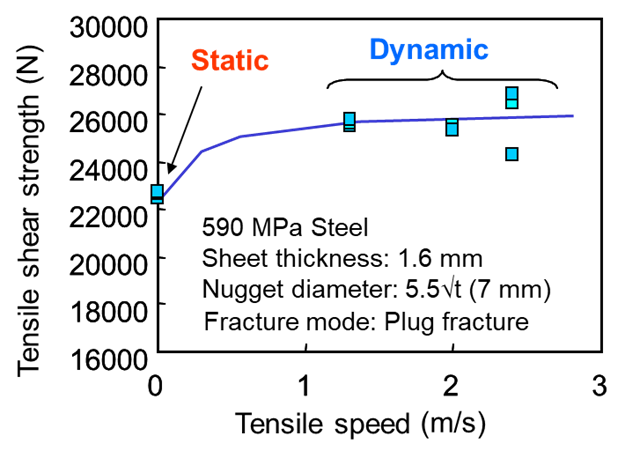

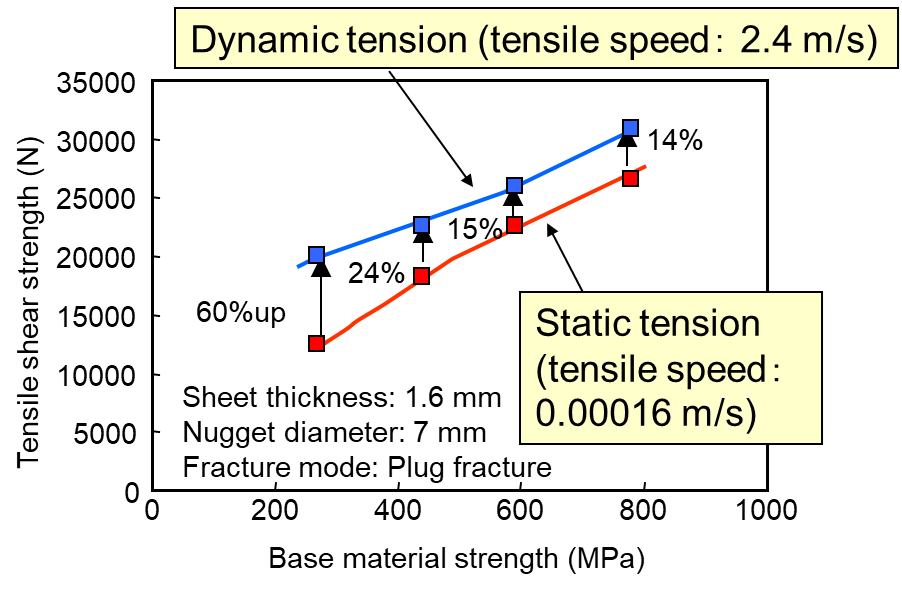

Figure 3 illustrates the effect of the tensile strength of the base material on the rate of increase in dynamic strength relative to static strength. Plug fracture remained the consistent failure mode across all cases. For the steel sheet with a rated tensile strength of 270 MPa, dynamic strength increased by approximately 60% compared to static strength. In contrast, the sheet with a rated tensile strength of 780 MPa showed an increase of only about 14%. These results indicate a tendency for the rate of increase in dynamic strength relative to static strength to decrease as the rated tensile strength of the steel increases. This is consistent with the general trend of mild steel strength increasing with strain rate, while strain rate sensitivity diminishes for higher-strength steels.

Figure 3: Relationship between dynamic and static tensile shear strengths of spot welds and base material strength

Source

Dynamic Tensile Shear Strength of Spot-Welded Joints: Experimental Investigation and Results Hiroki Fujimoto, Welding & Joining Research Laboratories, Nippon Steel Corporation

The article “Paint Bake Effect on Generation 3 Steel Weld Strength Compared to Other AHSS” by Richard H. Wolf explores the strength increase of resistance spot welds (RSW) in Generation 3 (Gen3) advanced high strength steels (AHSS) due to the paint bake-hardening effect.

These steels, due to their carbon content, may yield welds that can be brittle. A crucial, and often overlooked, aspect of the automotive production process is the paint bake stage, which has been shown to improve the mechanical properties of AHSS welds. In order to correctly assess the strength of a weld, this article proposes to take the paint-bake effect into account.

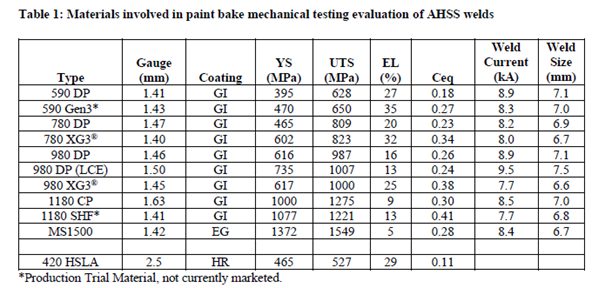

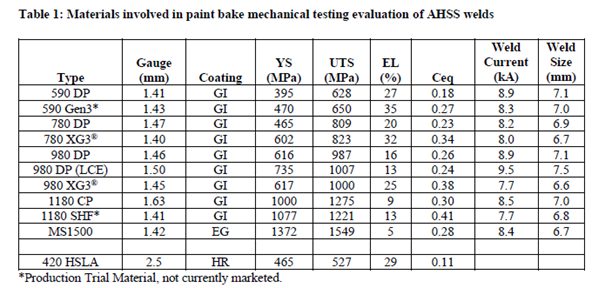

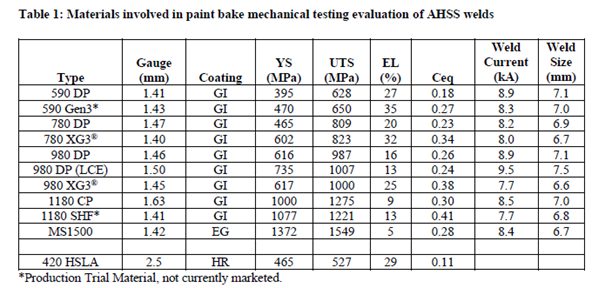

Table 1: Materials tested.

The experimental phase involved various AHSS materials, primarily with 1.5 mm thickness, with differing yield strengths and carbon equivalencies (Ceq). Resistance spot welding was performed under controlled conditions, and the effects of different paint bake temperatures and durations were analyzed.

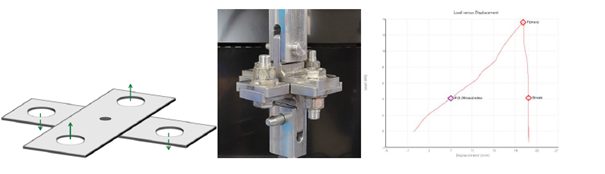

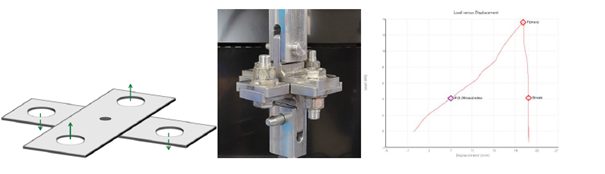

Figure 1: Testing setup

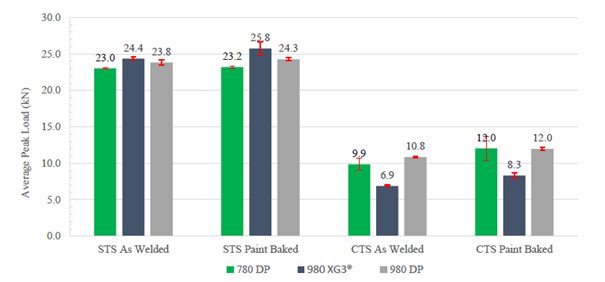

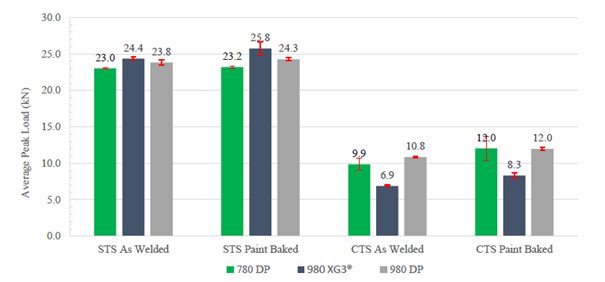

Results indicated that Gen3 steels exhibited a significant increase in weld strength following paint baking, particularly in cross-tension strength (CTS) tests. Higher Ceq values correlated with lower weld strength in the as-welded state, while the paint bake effect tended to equalize these strengths across different alloys.

Figure 2: Comparison of shear-tensile strength and cross-tensile strength of different steels with and without paint baking. Especially in cross-tensile testing, a significant increase in load-bearing capacity is visible.

Hardness testing revealed a softening in the heat-affected zone after baking, suggesting that the weld microstructure became more homogenous, which reduces brittleness and improves fracture behavior. The investigation into heterogeneous welding between different steel types further elucidated the contribution of the fusion zone and heat-affected zone to overall weld strength.

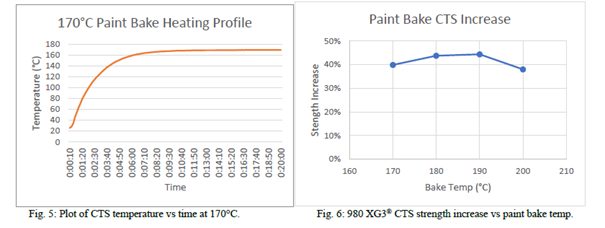

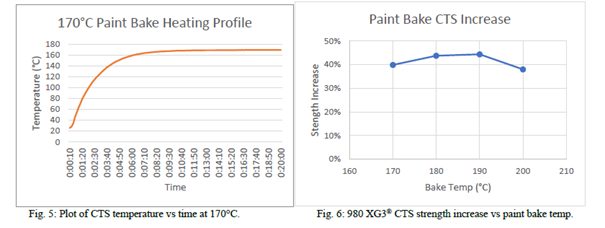

Figure 3: Utilized paint baking profile and cross-tensile strength increase

In conclusion, the paint bake process significantly enhances the strength of AHSS welds, especially for Gen3 steels. This improvement should be factored into weld strength modeling for automotive applications. The author suggests establishing standardized paint bake simulations to ensure weld properties are accurately represented for automotive manufacturers.

Source

Richard H. Wolf, Paint Bake Effect on Generation 3 Steel Weld Strength Compared to Other AHSS

Blog, homepage-featured-top, Joining Dissimilar Materials, main-blog

The discussions relative to cold stamping are applicable to any forming operation occurring at room temperature such as roll forming, hydroforming, or conventional stamping. Similarly, hot stamping refers to any set of operations using Press Hardening Steels (or Press Quenched Steels), including those that are roll formed or fluid formed.

Automakers contemplating whether a part is cold stamped or hot formed must consider numerous factors. This blog covers some important considerations related to welding these materials for automotive applications. Most important is the discussion on Resistance Spot Welding (RSW) as it is the dominating process in automotive manufacturing.

Setting Correct Welding Parameters for Resistance Spot Welding

Specific welding parameters need to be developed for each combination of material type and thickness. In general, the Hot Press (HP) steels require more demanding process conditions. One important factor is electrode force which should be higher for the HP steel than for cold press type steel of the same thickness. The actual recommended force will depend on the strength level, and the thickness of the steel. Of course, this will affect the welding machine/welding gun force capability requirement.

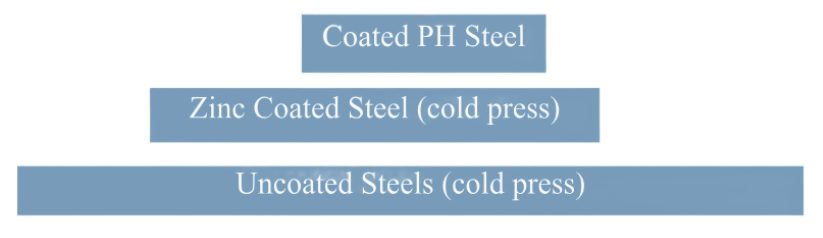

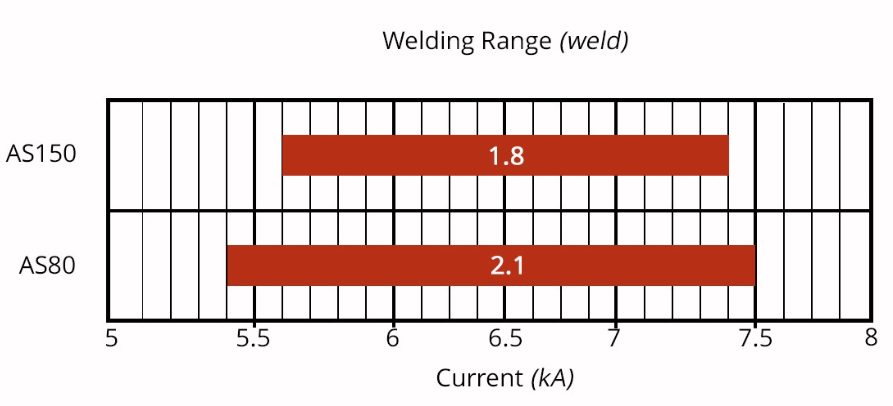

Another important variable is the welding current level and even more important is the current range at which acceptable welds can be made. The current range is weldability measurement, and the best indicator of the welding process robustness in the manufacturing environment and sometime called proceed window. Note the relative range of current for different steel types. A smaller process window may require more frequent weld quality evaluation such as for weld size.

Relative Current Range (process windows) for Different Steel Types

The Effect of Coating Type on Weldability

In all cases of resistance spot welding coated steels, it is imperative to move the coating away from the weld area during and in the beginning of the weld cycle to allow a steel-to-steel weld to occur. The combination of welding current, weld time and electrode force are responsible for this coating displacement.

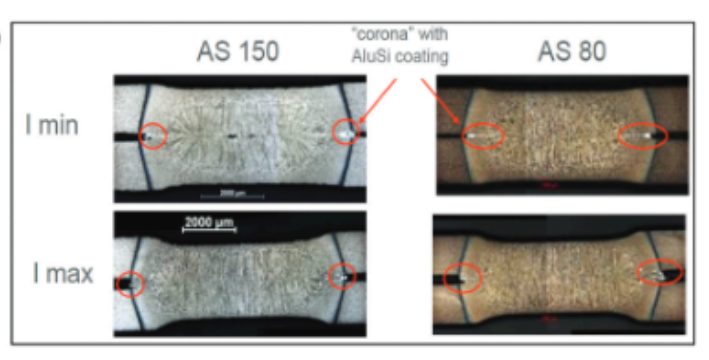

For all the coated steels, the ability of the coating to flow is a function of the coating type and properties, such as electrical resistivity and melting point, as well as the coating thickness.

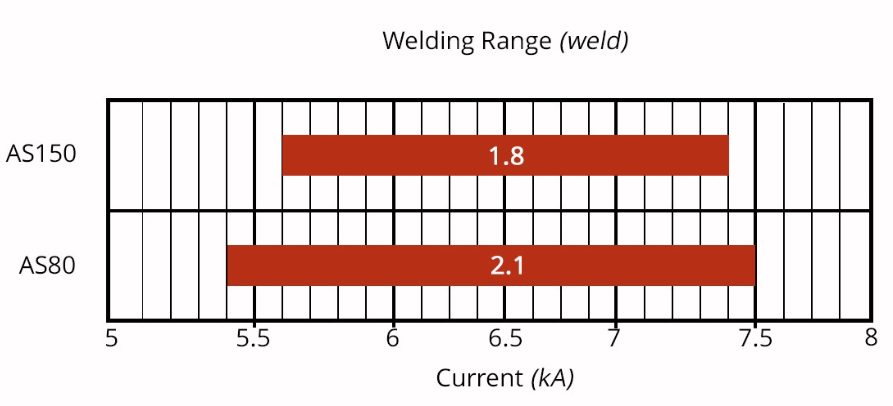

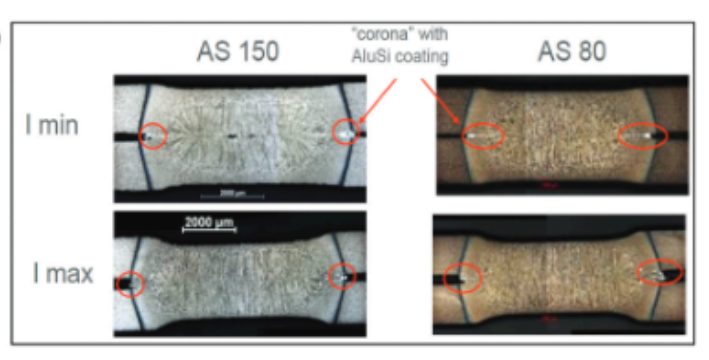

An example of cross sectioned spot welds made on Hot Press Steel with Aluminum -Silicon coating is shown below. It shows two coating thicknesses and the displaced coating at the periphery of weld. This figure also shows the difference in current range for the different coating thickness. The thicker coating shows a smaller current range. In addition, the Al-Si coating has a much higher melting point than the zinc coatings on the cold stamped steels, making it more difficult to displace from the weld area.

Hot Press Steel with Aluminum -Silicon

Liquid Metal Embrittlement and Resistance Spot Welding

Cold-formable, coated, Advance High Strength Steels such as the 3rd Generation Advanced High Strength Steels are being widely used in automotive applications. One welding issue these materials encounter is the increased hardness in the weld area, that sometime results in brittle fracture of the weld.

Another issue is their sensitivity to Liquid Metal Embrittlement (LME) cracking. These two issues are discussed in detail on the WorldAutoSteel AHSS Guidelines website and our recently released Phase 2 Report on LME.

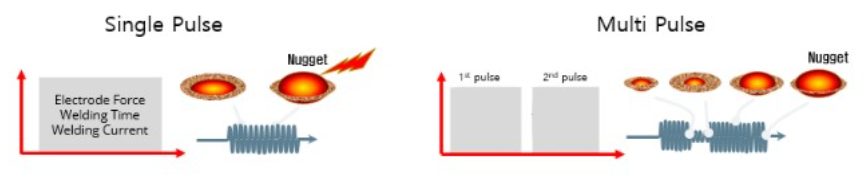

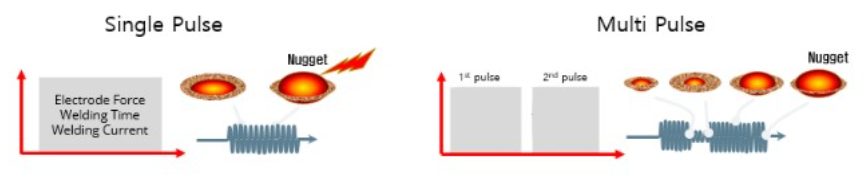

Resistance Spot Welding Using Current Pulsation

The most effective solution for the issues described above is using current pulsation during the welding cycle. A schematic description is shown below.

The pulsation allows much better control of the heat generation and the weld nugget development. The pulsation variables include the number of pulses (typically 2-4), the current level and time for each pulse, and the cool time between the pulses.

In summery, pulsation (and sometime current upslope) in Resistance Spot Welding proved to be beneficial for the following applications:

- Coated Cold Stamped steels

- Cold stamped Advance High Strength Steels

- Multi materials stack-ups – As described in our articles here on 3T/4T and 5T Stack-Ups

Thanks is given to Menachem Kimchi, Associate Professor-Practice, Dept of Materials Science, Ohio State University and Technical Editor – Joining, AHSS Application Guidelines, for this article.

Blog, homepage-featured-top, Joining, Joining Dissimilar Materials, main-blog, News, Resistance Spot Welding, Resistance Welding Processes, RSW Modelling and Performance, RSW of Dissimilar Steel

This blog is a short summary of a published comprehensive research work titled: “Peculiar Roles of Nickel Diffusion in Intermetallic Compound Formation at the Dissimilar Metal Interface of Magnesium to Steel Spot Welds” Authored by Luke Walker, Carolin Fink, Colleen Hilla, Ying Lu, and Wei Zhang; Department of Materials Science and Engineering, The Ohio State University

*****

There is an increased need to join magnesium alloys to high-strength steels to create multi-material lightweight body structures for fuel-efficient vehicles. Lightweight vehicle structures are essential for not only improving the fuel economy of internal combustion engine automobiles but also increasing the driving range of electric vehicles by offsetting the weight of power systems like batteries.

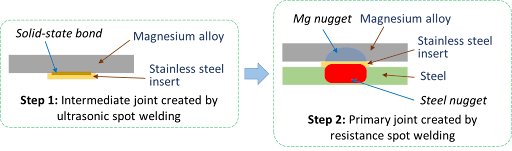

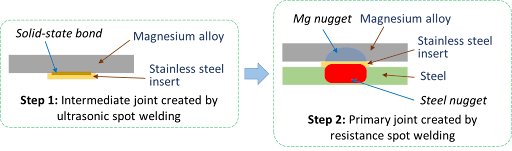

To create these structures, lightweight metals, such as magnesium (Mg) alloys, have been incorporated into vehicle designs where they are joined to high strength steels. It is desirable to produce a metallurgical bond between Mg alloys and steels using welding. However, many dissimilar metal joints form intermetallic compounds (IMCs) that are detrimental to joint ductility and strength. Ultrasonic interlayered resistance spot welding (Ulti-RSW) is a newly developed process that has been used to create strong dissimilar joints between aluminum alloys and high-strength steels. It is a two-step process where the light metal (e.g., Al or Mg alloy) is first welded to an interlayer (or insert) material by ultrasonic spot welding (USW). Ultrasonic vibration removes surface oxides and other contaminates, producing metal-to-metal contact and, consequently, a metallurgical bond between the dissimilar metals. In the second step, the insert side of the light metal is welded to steel by the standard resistance spot welding (RSW) process.

Cross-section View Schematics of Ulti-RSW Process Development

Cross-section View Schematics of Ulti-RSW Process Development

For resistance spot welding of interlayered Mg to steel, the initial schedule attempted was a simple single pulse weld schedule that was based on what was used in our previous study for Ulti-RSW of aluminum alloy to steel . However, this single pulse weld schedule was unable to create a weld between the steel sheet and the insert when joining to Mg. Two alternative schedules were then attempted; both were aimed at increasing the heat generation at the steel-insert interface. The first alternative schedule utilized two current pulses with Pulse 1, high current displacing surface coating and oxides and Pulse 2 growing the nugget. The other pulsation schedule had two equal current pulses in terms of current and welding time.

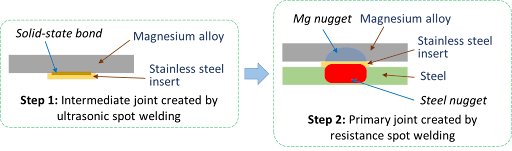

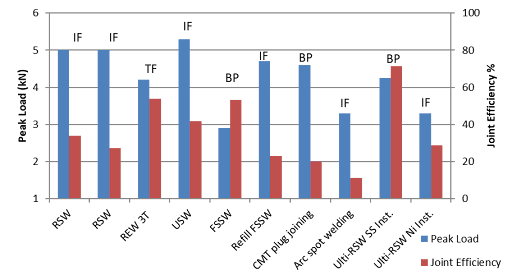

Lap shear tensile testing was used to evaluate the joint strength using the stack-up schematically, shown below. Note the images of Mg and steel sides of a weld produced by Ulti-RSW.

Lap Shear Tensile Test Geometry and the Resultant Weld Nuggets

Lap Shear Tensile Test Geometry and the Resultant Weld Nuggets

An example of a welded sample showed a distinct feature of the weld that is comprised of two nuggets separated by the insert: the steel nugget formed from the melting of steel and insert and the Mg nugget brazed onto the unmelted insert. This feature is the same as that of the Al-steel weld produced by Ulti-RSW in our previous work. Although the steel nugget has a smaller diameter than the Mg nugget, it is stronger than the latter, so the failure occurred on the Mg sheet side.

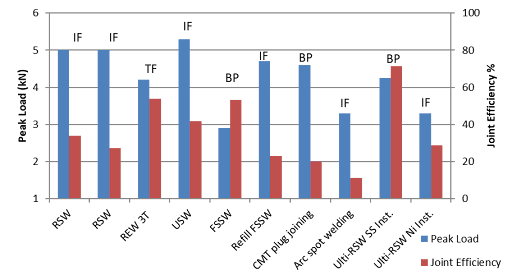

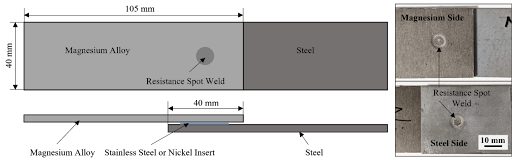

Joint strength depends on several factors, including base metal strength, sheet thickness, and nugget size, making it difficult to compare how strong a weld truly is from one process to another. To better compare the dissimilar joints created by different processes, joint efficiency, a “normalized” quantity was calculated for various processes used for dissimilar joining of Mg alloys to steels in the literature, and those results, along with the efficiencies of Ulti-RSW with inserts, are shown together below. Most of the literature studies also used AZ31 as the magnesium base metal. The ones with high joint efficiency (about 53%) in the literature are resistance element welding (REW) and friction stir spot welding (FSSW). In our study, Ulti-RSW with SS316 insert was able to reach an excellent joint efficiency of 71.3%, almost 20% higher than other processes.

Process Evaluation and Comparison

Process Evaluation and Comparison

Thanks are given to Menachem Kimchi, Associate Professor-Practice, Dept of Materials Science, Ohio State University, and Technical Editor – Joining, AHSS Application Guidelines, for this article.