Blog, homepage-featured-top, main-blog

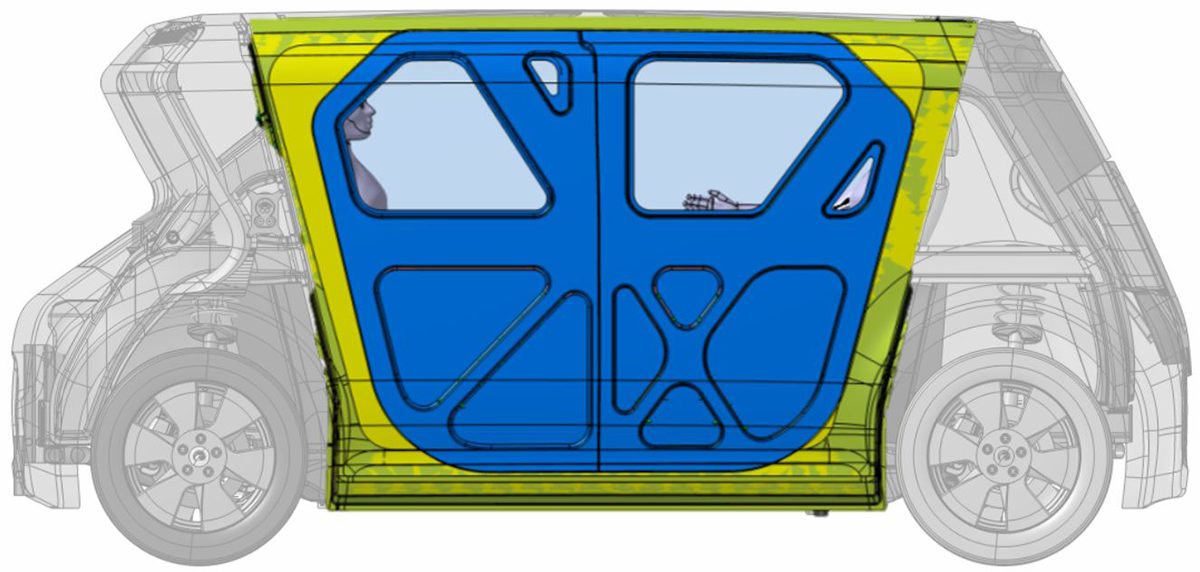

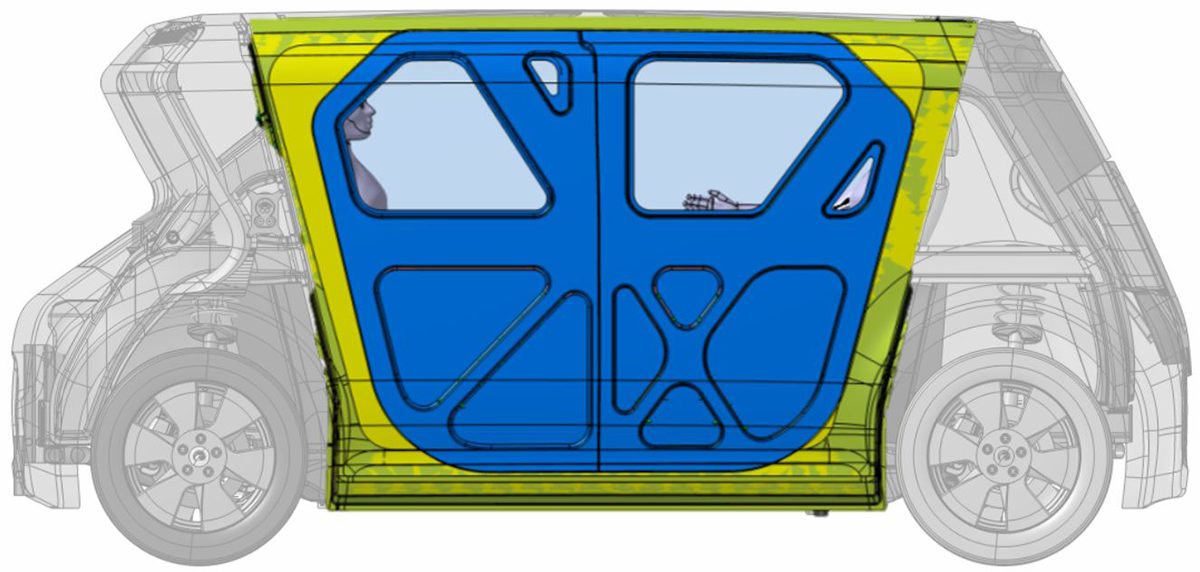

Steel E-Motive’s AHSS A- and C-Pillar placement provide good occupant protection in side pole crash scenarios. The A- and C-Pillar combined with AHSS door ring and door reinforcements compensate for the removed B-Pillar.

Since June 2020, we’ve been working with our engineering partners, Ricardo, on Steel E-Motive, a vehicle engineering program which is developing virtual concepts for two fully autonomous and connected electric vehicles designed for mobility as a service (MaaS) applications. We are using Advanced High-Strength Steel (AHSS) technologies and products to design autonomous vehicle concepts to enable MaaS solutions which are safe, affordable, accessible and environmentally conscious.

Steel E-Motive engineering and validation will be completed in 2022, at which time we will prepare communication and delivery of the final results. But right now, we are in the midst of crash simulation and material optimization to solve the new challenges posed by these vehicles.

Steel E-Motive is designed to operate in a mixed traffic mode operation (both driver-operated and autonomous vehicles); hence the vehicle should meet the current and future global high-speed crash test standards. The compact vehicle dimensions and proportions result in relatively short front and rear overhangs. To enhance user experience and take advantage of full autonomy, the front occupants are positioned in a rear facing configuration presenting a more significant challenge for crashworthiness in frontal impact. This requires a revised front crash strategy and load management approach for Steel E-Motive.

Neil McGregor, Steel E-Motive’s Chief Engineer, has written a blog about it, and you can find it posted on our Steel E-Motive website (web spiders prohibit us from duplicating the article here). Take a moment to read it there, but feel free to ask questions or comment about it here!

Blog, homepage-featured-top, main-blog

Our colleagues at JFE Steel recently provided us with a new case study based on laboratory evaluations they conducted in Japan. The article is part of our Martensite article, but we this month, we want to highlight it in our AHSS Insights blog.

Martensitic steel grades provide a cold formed alternative to hot formed press hardening steels. Not all product shapes can be cold formed. For those shapes where forming at ambient temperatures is possible, design and process strategies must address the springback which comes with the high strength levels, as well as eliminate the risk of delayed fracture. The potential benefits associated with cold forming include lower energy costs, reduced carbon footprint, and improved cycle times compared with hot forming processes.

Highlighting product forms achievable in cold stamping, an automotive steel Product Applications Laboratory formed a Roof Center Reinforcement from 1.4 mm CR1200Y1470T-MS using conventional cold stamping rather than roll forming, Figure 6. Using cold stamping allows for the flexibility of considering different strategies when die processing which may result in reduced springback or incorporating part features not achievable with roll forming.

Figure 6: Roof Center Reinforcement cold stamped from CR1200Y1470T-MS martensitic steel.U-1

Cold stamping of martensitic steels is not limited to simpler shapes with gentle curvature. Shown in Figure 7 is a Center Pillar Outer, cold stamped using a tailor welded blank containing CR1200Y1470T-MS and CR320Y590T-DP as the upper and lower portion steels.U-1

Figure 7: Center Pillar Outer stamped at ambient temperature from a tailor welded blank containing 1470 MPa tensile strength martensitic steel.U-1

Another characteristic of martensitic steels is their high yield strength, which is associated with improved crash performance. In a laboratory environment, crash behavior is assessed with 3-point bending moments. A studyS-8 determined there was a correlation between sheet steel yield strength and the 3-point bending deformation of hat shaped parts. Based on a comparison of yield strength, Figure 8 shows that CR1200Y1470T-MS has similar performance to hot stamped PHS-CR1800T-MB and PHS-CR1900T-MB at the same thickness and exceeds the frequently used PHS-CR1500T-MB. For this reason, there may be the potential to reduce costs and even weight with a cold stamping approach, providing appropriate press, process, and die designs are used.

Figure 8: Effect of Yield Strength on Bending Moment. The right image shows the typical yield strength range of CR1030Y1300T-MS and CR1200Y1470T-MS as well as typical yield strength values of several Press Hardened Steels.S-8

To read more about Martensitic steels, including its practical applications, visit the Steel Grades page here.

Many thanks to Toshiaki Urabe, Principal Researcher, JFE Steel, and Dr. Daniel Schaeffler, President, Engineering Quality Solutions, Inc., for providing this case study.

Blog, homepage-featured-top, main-blog

One of the tasks we took great care in completing during the update of the AHSS Application Guidelines was to provide a definition for what constitutes a third generation (3rd Gen) Advanced High-Strength Steel. We had been asked this question many times, and often in addressing the question among our technical editors, we would get various responses. Consequently, we made it a part of a discussion with our AHSS Guidelines Working Group, made up of steel subject matter experts from around the world at our member companies. The following article reflects the outcome of that discussion and is the definition adopted by WorldAutoSteel.

First Generation Advanced High-Strength Steels (AHSS) are based on a ferrite matrix for baseline ductility, with varying amounts of other microstructural components like martensite, bainite, and retained austenite providing strength and additional ductility. These grades have enhanced global formability compared with conventional high strength steels at the same strength level. However, local formability challenges may arise in some applications due to wide hardness differences between the microstructural components.

The Second Generation AHSS grades have essentially a fully austenitic microstructure and rely on a twinning deformation mechanism for strength and ductility. Austenitic stainless steels have similar characteristics, so they are sometimes grouped in this category as well. 2nd Gen AHSS grades are typically higher-cost grades due to the complex mill processing to produce them as well as being highly alloyed, the latter of which leads to welding challenges.

Third Generation (or 3rd Gen) AHSS are multi-phase steels engineered to develop enhanced formability as measured in tensile, sheared edge, and/or bending tests. Typically, these steels rely on retained austenite in a bainite or martensite matrix and potentially some amount of ferrite and/or precipitates, all in specific proportions and distributions, to develop these enhanced properties.

Individual automakers may have proprietary definitions of 3rd Gen AHSS grades containing minimum levels of strength and ductility, or specific balances of microstructural components. However, such globally accepted standards do not exist. Prior to 2010, one steelmaker had limited production runs of a product reaching 18% elongation at 1000 MPa tensile strength. Starting around 2010, several international consortia formed with the hopes of achieving the next-level properties associated with 3rd Gen steels in a production environment. One effortU-11, S-95 targeted the development of two products: a high strength grade having 25% elongation and 1500 MPa tensile strength and a high ductility grade targeting 30% elongation at 1200 MPa tensile strength. The “exceptional-strength/high-ductility” steel achieved 1538 MPa tensile strength and 19% elongation with a 3% manganese steel processed with a QP cycle. The 1200 MPa target of the “exceptional-ductility/high-strength” was met with a 10% Mn alloy, and exceeded the ductility target by achieving 37% elongation. Another effort based in EuropeR-22 produced many alloys with the QP process, including one which reached 1943 MPa tensile strength with 8% elongation. Higher ductility was possible, at the expense of lower strength.

3rd Gen steels have improved ductility in cold forming operations compared with other steels at the same strength level. As such, they may offer a cold forming alternative to press hardening steels in some applications. Also, while 3rd Gen steels are intended for cold forming, some are appropriate for the hot stamping process.

Like all steel products, 3rd Gen properties are a function of the chemistry and mill processing conditions. There is no one unique way to reach the properties associated with 3rd Gen steels – steelmakers use their available production equipment with different characteristics, constraints, and control capabilities. Even when attempting to meet the same OEM specification, steelmakers will take different routes to achieve those requirements. This may lead to each approved supplier having properties which fall into different portions of the allowable range. Manufacturers should use caution when switching between suppliers, since dies and processes tuned for one set of properties may not behave the same when switching to another set, even when both meet the OEM specification.

There are three general types of 3rd Gen steels currently available or under evaluation. All rely on the TRIP effect. Applying the QP process to the other grades below may create additional high-performance grades.

- TRIP-Assisted Bainitic Ferrite (TBF) and Carbide-Free Bainite (CFB)

- TRIP-Assisted Bainitic Ferrite (TBF) and Carbide-Free Bainite (CFB) are descriptions of essentially the same grade. Some organizations group Dual Phase – High Ductility (DP-HD, or DH) in with these. Their production approach leads to an ultra-fine bainitic ferrite grain size, resulting in higher strength. The austenite in the microstructure allows for a transformation induced plasticity effect leading to enhanced ductility.

- Quenched and Partitioned Grades, Q&P or simply QP

- Quenching and Partitioning (Q&P) describes the processing route resulting in a structure containing martensite as well as significant amounts of retained austenite. The quenching temperature helps define the relative percentages of martensite and austenite while the partitioning temperature promotes an increased percentage of austenite stabile room temperature after cooling.

- Medium Manganese Steels, Medium-Mn, or Med-Mn

- Medium Manganese steels have a Mn content of approximately 3% to 12%, along with silicon, aluminum, and microalloying additions. This alloying approach allows for austenite to be stable at room temperature, leading to the TRIP Effect for enhanced ductility during stamping. These grades are not yet widely commercialized.

We have much more information on 3rd Gen steels here in the Guidelines. Take a look at the full 3rd Generation Steels article for much more detail on the three types listed above.

Blog, homepage-featured-top, main-blog

The rule of thumb estimates used in 1989 during my internship with an automotive stamping supplier were simple calculations for the peak load. Tonnage for trim and pierce operations depended on the length of line of trim, material thickness and the shear strength of the material. Tonnage for forming operations depended on the size of the form, material thickness and material tensile strength. These calculations typically over-predicted the tonnage requirement, but due to the relatively low strength compared to AHSS, the overall part size that dictated the required press size became the limiting factor rather than the tonnage requirement.

Applying these same rules of thumb to the advanced steels in use today will likely under-predict the tonnage requirements. To understand why, let us examine the guidelines I used over 30 years ago.

For piercing a hole: Tonnage = d * t * 80 Equation 1

In this equation d is the punch diameter in inches, t is the material thickness in inches, and it calculates tonnage in tons. This was a simple and effective way to estimate the tonnage of all the holes pierced. Equation 1 is a simplification of the proper calculation being the length of line doing the work, in this case the circumference of a circle, multiplied by the sheet thickness and the material’s shear strength (ꚍ). The generic equation for any type of piercing or trimming is Tonnage = P * t * ꚍ where P is the perimeter or length of line of the trim, t is the sheet thickness and ꚍ is the shear strength of the material. A typical estimate for the shear strength (ꚍ) of mild steel is 60% of the tensile strength (T). Therefore, the equation development for a simple hole piercing looks like:

| Generic trim equation: |

Tonnage = P * t * ꚍ |

Equation 2 |

| Specific for a round hole: |

Tonnage = πd * t * 0.6T |

|

| Simplifying: |

Tonnage = d * t * 0.6Tπ |

|

| Mild steel T = 300 MPa = 43.5 ksi: |

0.6 * 43.5 * 3.14 = 82 |

|

| Pierce a round hole: |

Tonnage = d * t * 80 |

|

Knowing how the rule of thumb was derived allows us to highlight some possible sources of error. First, the equation assumes trimming of the full thickness. In reality, a typical trim operation for steel consists of 20% to 50% trimming and the remainder is breakage. The press needs to apply load only for the trimming portion. Second, shear strength is not a fixed percentage of tensile strength. The actual shear strength should be measured for each specific grade as the microstructure differences of the AHSS will affect the material strength in shear. Lastly each of these errors are multiplied since today’s AHSS material has a tensile strength of three to five times that of mild steel. To see this, we can consider a simple example of piercing a 1-inch hole in 0.06 inch (1.5 mm) thick mild steel. Mild steel tensile strength typically ranges from 40 ksi to 55 ksi (280 MPa to 380 MPa). Looking at Equation 1 relative to Equation 2 with low- and high -end assumptions:

| Equation 1 estimate |

Tonnage = 1 * 0.06 * 80 = 4.8 tons |

| Equation 2 minimum |

Tonnage = 3.14 * 0.06(20%) * 0.6(40) = 0.9 tons |

| Equation 2 maximum |

Tonnage = 3.14 * 0.06(50%) * 0.6(55) = 3.1 tons |

This simple example shows sources of error that could lead to an estimate ranging from 0.9 to 4.8 tons to pierce a single hole. A similar exercise could apply to a drawing operation. In this situation, most rules of thumb attempt to use the perimeter or surface area of the part, the material thickness and the material tensile strength to predict the tonnage needed. Sources for error in this type of calculation include: 1) Using the perimeter of the draw area, tending to under-predict; 2) Using the surface area of the part, tending to over-predict; and 3) Using the tensile strength of the material, also tending to over-predict as it assumes the material is stretched right to the level of splitting. Correction factors have been developed over time, but it is still easy to see there are many possible sources of error in these types of calculations.

AHSS Magnifies Press Tonnage Prediction Challenges

A number of reasons explain why the inherent challenges with old-school rules of thumb are exaggerated with AHSS:

- Strength: The strength of today’s cold stamped steels is quite incredible. Where a mild steel may have a tensile strength of 280 MPa, it is now common to cold stamp dual phase (DP) steels and 3rd Generation steels with up to 1180 MPa. In addition, new materials having a tensile strength of 1500 MPa with enough elongation to allow for cold stamping are starting to enter the market. This five-fold increase in strength acts as a multiplying factor for any errors in traditional predictions.

- Formability: The formability of AHSS has also increased dramatically. Today a DP 590 steel and even a 980 3rd Generation steel can have nearly the same elongation as a high-strength low alloy (HSLA) steel of 30 years ago. This affords the part designers the ability to incorporate more complex forms into a part including using darts and beads to increase a part’s stiffness, tight radii and deeper draws. All of these add to the tonnage used and are generally not part of the old school rule of thumb calculations.

- Springback Corrections: Springback is linearly related to the yield strength of a material. Therefore, stamping AHSS grades require more features to be added to the die process to control springback. These may include draw beads (used to control material flow early in the press stroke), stake beads (used at the bottom of the stroke to minimize springback) and tighter radii (Figure 2). These features are typically off product, in the addendum, and are easily ignored by typical rule of thumb calculations.

Figure 2: Draw and Stake Bead PlacementA-6

- Hardening Curves: The complex microstructure of AHSS offers many advantages to increase formability. All AHSS grades produce microstructural phase transformations during the stamping process. This allows the lower yield strength in the as-rolled material, which aids in formability, to increase during the stamping operation. This yield strength increase can be as much as 100 MPa. Models that estimate these hardening curves of the material are ignored when doing hand calculations.

- Other Considerations: Lastly the typical rule of thumb calculations, as we have discussed, only consider the part characteristics. They generally do not include the other sources that consume energy during the stamping process including off-product feature (beads, pilot holes, etc.), spring stripper pressure, pad pressure from nitrogen springs or air cushions, driven cams and part lifters. Many of these could be ignored 30 years ago with mild steels, but they become more significant with the strength of today’s AHSS.

Next Steps

Accurately predicting press requirements is a decades-long, industry-wide issue. Auto/Steel Partnership (A/SP), a partnership between automotive OEMs, steel mills and affiliate suppliers, teamed up with formability software suppliers to improve press tonnage prediction accuracy. A/SP’s efforts, including this project, looks to bridge the gap between research laboratories and the shop floor.

Stamping companies should keep press tonnage monitors in good working order, and upgrade to systems that can capture full through-stroke force curves. Engaging with organizations like A/SP, OEMs and steel mills, allows efficient information sharing and capturing best-practices. Get the steel mill involved early, even in the die design phase. All steel mills have teams of application engineers to help OEMs and their suppliers transition into using the newest grades of steel – they want stampers to succeed and have the tools and data to help.

Read more about Press Tonnage Prediction in the expanded article.

Blog, homepage-featured-top, main-blog

Advanced High-Strength Steel (AHSS) products have significantly different forming characteristics and these challenge conventional mechanical and hydraulic presses. Some examples include the dramatically higher strength of these new steels resulting in higher forming loads and increased springback. Also, higher contact pressures cause higher temperatures at the die-steel interface, requiring high performance lubricants and tool steel inserts with advanced coatings.

These and other challenges lead to issues with the precision of part formation and stamping line productivity. Using a servo-driven press is one approach to address the challenges of forming and cutting AHSS grades. Recent growth in the use of servo presses in the automotive manufacturing industry parallels the increased use of AHSS in the body structure of new automobiles. Click to read more about the Characteristics of Servo Presses and their Advantages.

Figure 1 shows the difference between the available motions of flywheel-driven mechanical presses verses servo driven mechanical presses. The slide motion of the servo press can be programmed for more parts per minute, decreased drawing speed to reduce quality errors, or dwelling or re-striking at bottom dead center to reduce springback.

Figure 1: Comparison of Press Signatures in Fixed Motion Mechanical Presses and Free-Motion Servo-Driven Presses.M-3

Press Force and Press Energy

Categorizing both mechanical and hydraulic presses requires three different capacities or ratings – force, energy, and power. Historically, when making parts out of mild steel or even some HSLA steels, using the old rules-of-thumb to estimate forming loads was sufficient. Once the tonnage requirements and some processing requirements were known, stamping could occur in whichever press met those minimum tonnage and bed size requirements.

In these cases, press capacity (for example, 1000 kN) is a suitable number for the mechanical characteristics of a stamping press. Capacity, or tonnage rating, indicates the maximum force that the press can apply without damaging its components, like the machine frame, slide-adjusting mechanisms, pitman (connection rods) or main gear bushings.

A servo press transmits force (not energy) the same way as the equivalent conventional press (mechanical or hydraulic). However, the amount of force available throughout the stroke depends on whether the press is hydraulic or mechanically driven. Hydraulic presses can exert maximum force during the entire stroke as tonnage generation occurs via hydraulic fluid, pumps, and cylinders. Mechanical presses exert their maximum force at a specific distance above bottom dead center (BDC), usually defined at 0.5 inch. At increased distances above bottom dead center, the loss of mechanical advantage reduces the tonnage available for the press to apply. This phenomenon is known as de-rated tonnage, and it applies to conventional mechanical presses as well as servo-mechanical presses. Figure 2 shows a typical press-force curve for a 600-ton mechanical press. In this example, when the press is approximately 3 inches off BDC, the maximum tonnage available is only 250 tons – significantly less than the 600-ton rating.

Figure 2: The Press-Force curve shows the maximum tonnage a mechanical press can apply based on the position of the slide relative to the bottom dead center reference distance. This de-rated tonnage applies to both conventional mechanical presses as well as servo-mechanical presses.E-2

Press energy reflects the ability to provide that force over a specified distance (draw depth) at a given cycle rate. Figure 3 shows a typical press-energy curve for the same 600-ton mechanical press. The energy available depends on the size and speed of the flywheel, as well as the size of the main drive motor. As the flywheel rotates faster, the amount of stored energy increases, reflected in the first portion of the curve. The cutting or forming process consumes energy, which the drive motor must replenish during the nonworking part of the stroke. At faster speeds, the motor has less time to restore the energy. If the energy cannot be restored in time, the press stalls. The graph illustrates how the available energy of the press diminishes to 25% of the rated capacity when accompanied by a speed reduction from 24 strokes per minute to 12 strokes per minute.

Figure 3: A representative press-energy curve for a 600 ton mechanical press. Reducing the stroke rate from 24 to 12 reduces available energy by 75%.E-2

Case Study: Press Force and Press EnergyH-3

Predicting the press forces needed initially to form a part is known from a basic understanding of sheet metal forming. Different methods are available to calculate drawing force, ram force, slide force, or blankholder force. The press load signature is an output from most forming-process development simulation programs, as well as special press load monitors. The topic of press force predictions will be covered in this Blog in the months ahead.

Most structural components include design features to improve local stiffness. Typically, forming of the features requiring embossing processes occurs near the end of the stroke near Bottom Dead Center. Predicting forces needed for such a process is usually based on press shop experiences applicable to conventional steel grades. To generate comparable numbers for AHSS grades, forming process simulation is recommended.

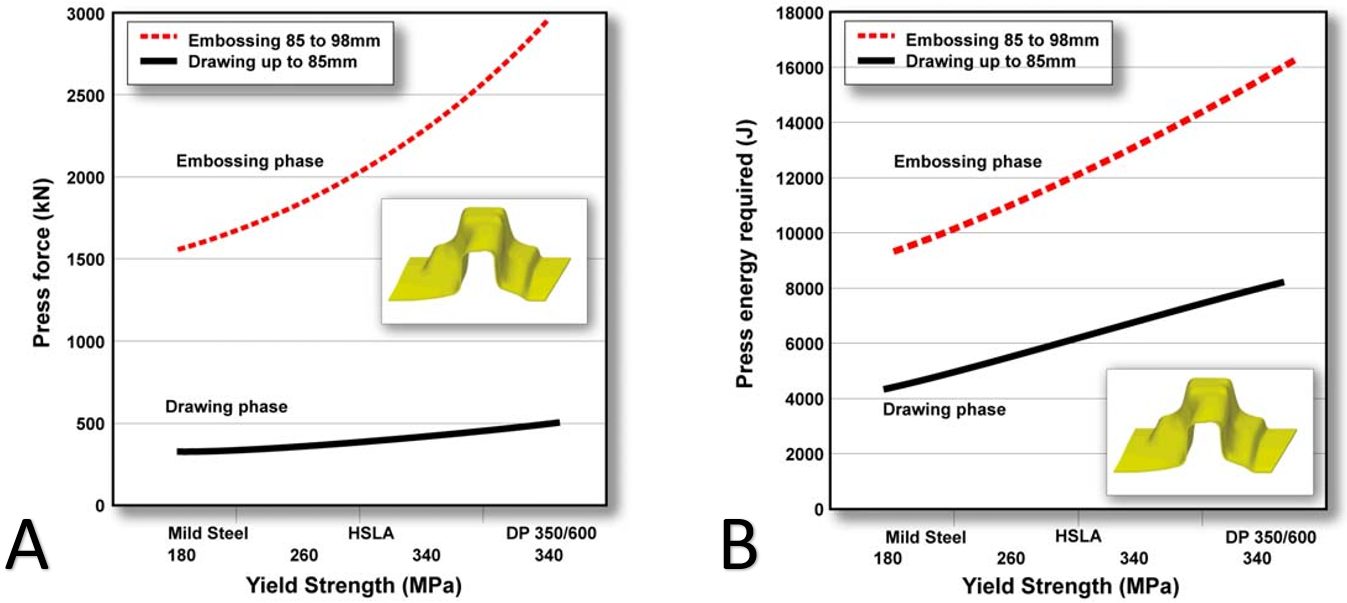

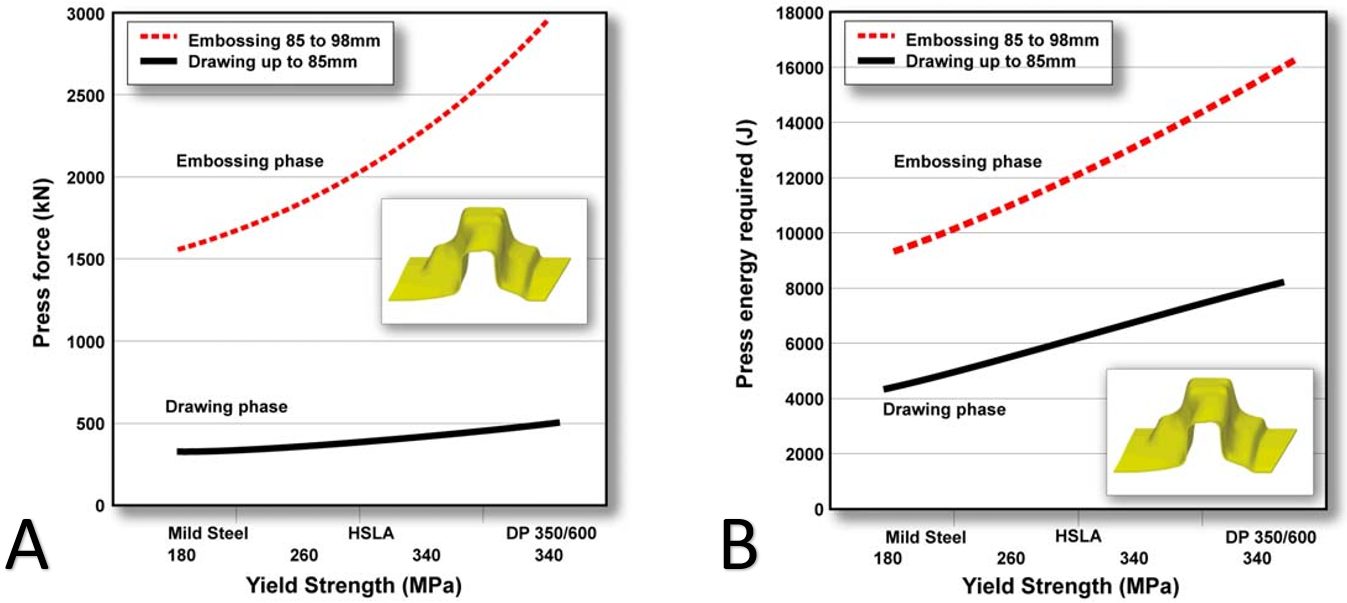

In Citation H-3, stamping simulations evaluated the forming of a cross member having a hat-profile with an embossment formed at the end of the stroke (Figure 4). The study simulated press forces and press energy involved for drawing and embossing a channel section from four steel grades approximately 1.5 mm thick: mild steel, HSLA 250/350, HSLA 350/450, and DP 350/600. Figures 5A and 5B clearly show that the embossing phase rather than the drawing phase dominates the total force and energy requirements, even though the punch travel for embossing is only a fraction of the drawing depth.

Figure 4: Cross section of a component having a longitudinal embossment to improve local stiffness.H-3

Figure 5: Embossing requires significantly more (A) force and (B) energy than drawing, even though the punch travel in the embossing stage is much smaller.H-3

Figures 6 and 7 highlight the press energy requirements, showing the greater energy required for higher strength steels. The embossment starts to form at a punch displacement of 85 mm, indicated by the three dots in Figure 6. The last increment of punch travel to 98 mm requires significantly higher energy, as shown in Figure 7. Note that compared with mild steel, the dual phase steel grade requires significantly more energy to form the part to home with the 98 mm travel.

Figure 6: Energy needed to form the component increases for higher strength steel grades. Forming the embossment begins at 85 mm of punch travel, indicated by the 3 dots.H-3

Figure 7: Additional energy required to form the embossment increases for higher strength steel grades.H-3

It is not only embossments that require substantially more force and energy at the end of the stroke. Stake beads for springback control engage late in the stroke to provide sidewall stretch. Depending on the design of the forming process, the steel into which the stake beads engage may have passed through conventional draw beads for metal flow control, and therefore are work-hardened to an even higher strength. This leads to greater requirements for die closing force and energy. Certain draw-bead geometries which demand different closing conditions around the periphery of the stamping also may influence closing force and energy requirements.

A more detailed Press Requirements article contains additional information and case studies. Read it here >>>

Blog, homepage-featured-top, main-blog

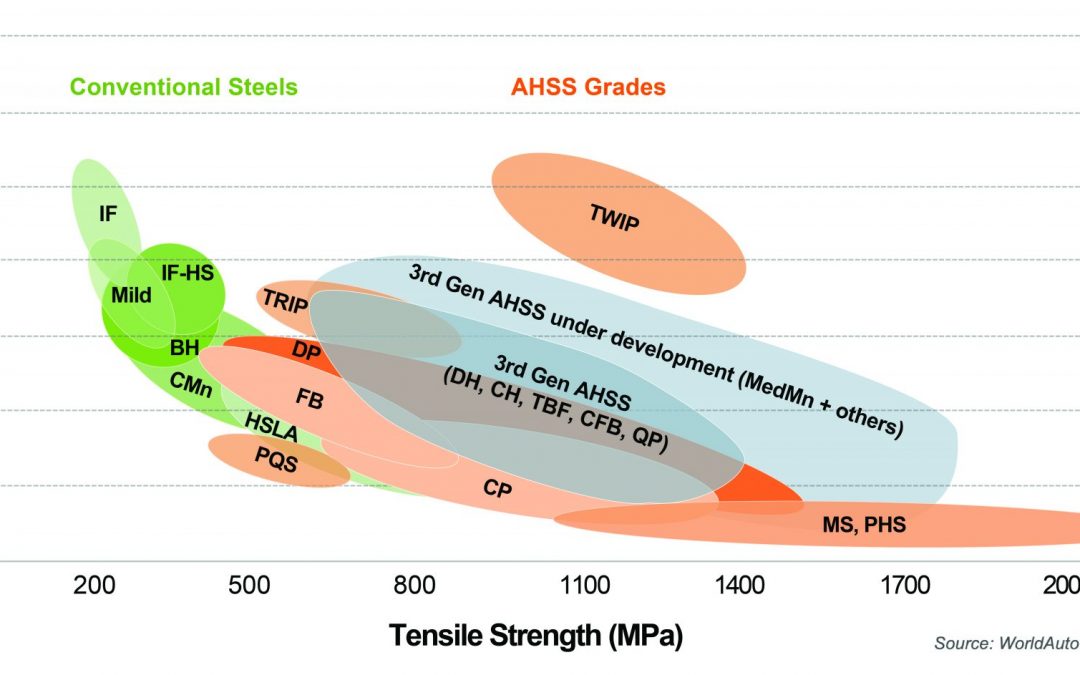

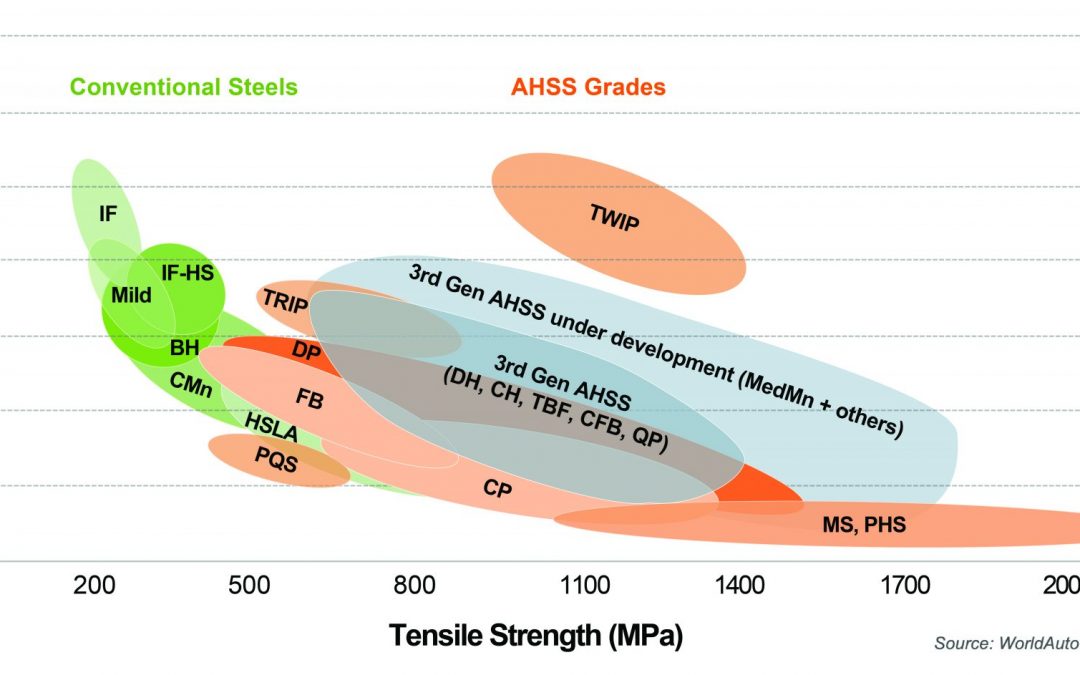

Bubble chart. Banana diagram. Steel strength ductility diagram—it’s been called a lot of things over the years. But the 2021 chart shown in Figure 1 is the subject of hundreds of requests for use we receive from engineers and students all over the world and appears in thousands of presentations and papers. Because of that, we periodically update it to make sure it reflects the most current picture of both commercially available, as well as emerging steel grades. In this blog, we are providing our updated GFD for download as well as definitions of steel classifications, as agreed to by our member companies.

Figure 1: The 2021 Global Formability Diagram comparing strength and elongation of current and emerging steel grades.

Steel Classifications

There are different ways to classify automotive steels. One is a metallurgical designation providing some process information. Common designations include lower-strength steels (interstitial-free and mild steels); conventional high strength steels, such as bake hardenable and high-strength, low-alloy steels (HSLA); and Advanced High-Strength Steels (AHSS) such as dual phase and transformation-induced plasticity steels. Additional higher strength steels include press hardening steels and steels designed for unique applications that have improved edge stretch and stretch bending characteristics.

A second classification method important to part designers is strength of the steel. This document will use the general terms HSLA and AHSS to designate all higher strength steels. The principal difference between conventional HSLA steels and AHSS is their microstructure. Conventional HSLA steels are single-phase ferritic steels with a potential for some pearlite in C-Mn steels.

AHSS are primarily steels with a multiphase microstructure containing one or more phases other than ferrite, pearlite, or cementite – for example martensite, bainite, austenite, and/or retained austenite in quantities sufficient to produce unique mechanical properties. Some types of AHSS have a higher strain hardening capacity resulting in a strength-ductility balance superior to conventional steels. Other types have ultra-high yield and tensile strengths and show a bake hardening behavior.

What are 3rd Gen Steels?

Third Generation, or 3rd Gen, AHSS builds on the previously developed 1st Gen AHSS (DP, TRIP, CP, MS, and PHS) and 2nd Gen AHSS (TWIP), with global commercialization starting around 2020. Third Gen AHSS are multi-phase steels engineered to develop enhanced formability as measured in tensile, sheared edge, and/or bending tests. Typically, these steels rely on retained austenite in a bainite or martensite matrix and potentially some amount of ferrite and/or precipitates, all in specific proportions and distributions, to develop these enhanced properties.

Graphical Presentation

Generally, elongation (a measure of ductility) decreases as strength increases. Plotting elongation on the vertical axis and strength on the horizontal axis leads to a graph starting in the upper left (high elongation, lower strength) and progressing to the lower right (lower elongation, higher strength). When considering conventional steels and the first generation of advanced high strength steels, this shape led to the colloquial description of calling this the banana diagram.

With the continued development of advanced steel options, it is no longer appropriate to describe the plethora of options as being in the shape of a banana. Instead, with new grades filling the upper right portion of Figure 1, perhaps it is more accurate to describe this as the football diagram as the options now start to fall into the shape of an American or Rugby Football. Officially, it is known as the steel Global Formability Diagram.

Even this approach has its limitations. Elongation is only one measure of ductility. Other ductility parameters are increasingly important with AHSS grades, such as hole expansion and bendability. There are several other approaches that have been proposed by experts around the world. Have a look at our Defining Steels article, from which this article was drawn, to learn more about them. You will also find within Defining Steels a detailed explanation of the nomenclature used throughout the Guidelines to define steels. If you have questions, please use the Comments tool below or on the Defining Steels page.

Download the GFD

Because of its popularity, we provide high resolution image files of the GFD here for your download and use. Please source it “Courtesy of WorldAutoSteel” in your papers and presentations. We are happy for you to use it. If you require our signed permission, please write us at steel@worldautosteel.org. We’ll respond quickly.

* The Guidelines use the general terms HSLA and AHSS to designate all higher strength steels.