Blog, homepage-featured-top, main-blog, News, Resistance Spot Welding, RSW of Dissimilar Steel, Tool & Die Professionals

Urbanization and waning interest in vehicle ownership point to new transport opportunities in megacities around the world. Mobility as a Service (MaaS) – characterized by autonomous, ride-sharing-friendly EVs – can be the comfortable, economical, sustainable transport solution of choice thanks to the benefits that today’s steel offers.

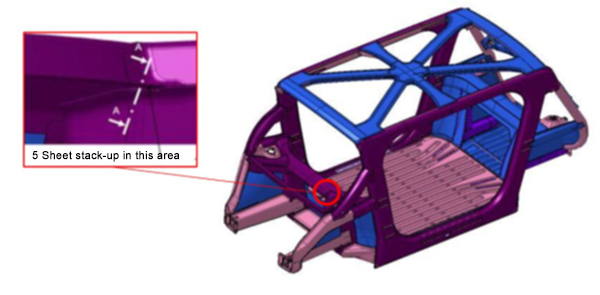

The WorldAutoSteel organization is working on the Steel E-Motive program, which delivers autonomous ride-sharing vehicle concepts enabled by Advanced High-Strength Steel (AHSS) products and technologies.

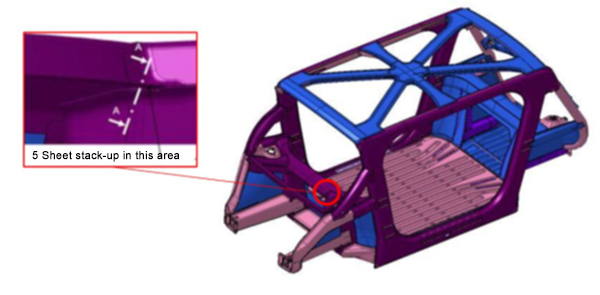

The Body structure design for this vehicle is shown in Figure 1. It also indicates the specific joint configuration of 5 layers AHSS sheet stack-up as shown in Table 1. Resistance spot welding parameters were developed to allow this joint to be made by a single weld. (The previous solution for this welded joint is to create one spot weld with the bottom 3 sheets indicated in the table and a second weld to join the top 2 sheets, combining the two-layer groups to 5T stack-up.)

NOTE: Click this link to read a previous AHSS Insights blog that summarizes development work and recommendations for resistance spot welding 3T and 4T AHSS stack-ups: https://bit.ly/42Alib8

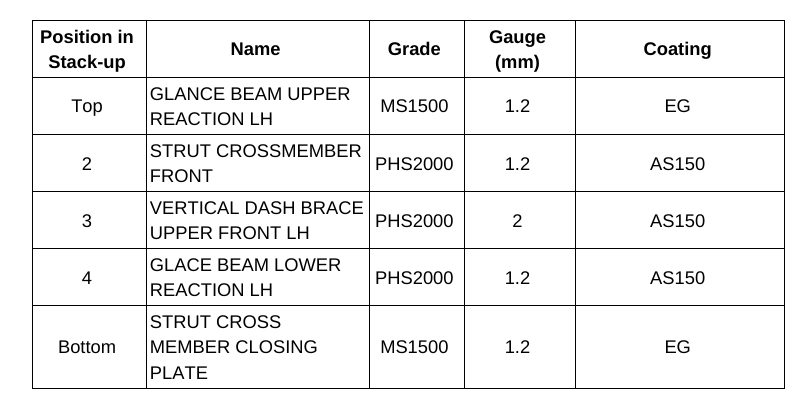

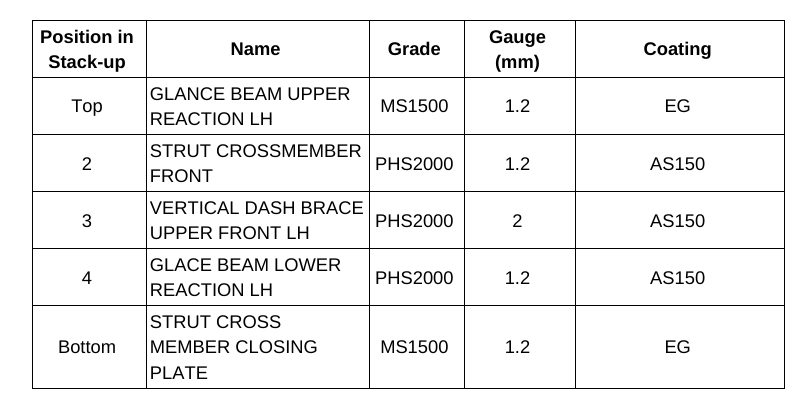

Table 1. Provided materials organized in stack-up formation showing part number, name, grade, gauge in mm, and coating type. Total thickness = 6.8 mm

The same approach of utilizing multiple current pulses with short cool time in between the pulses was shown to be most effective in this case of 5T stack-up. It is important to note that in some cases, the application of a secondary force was shown to be beneficial, however, it was not used in this example.

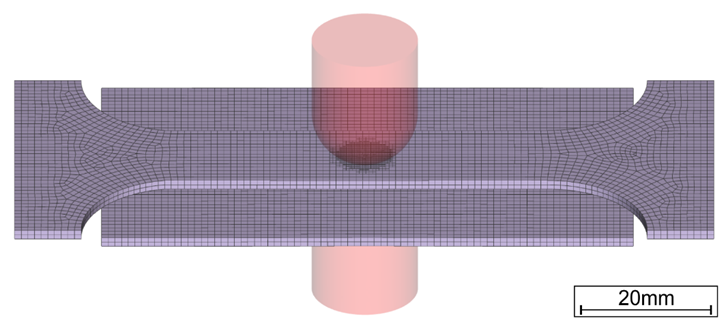

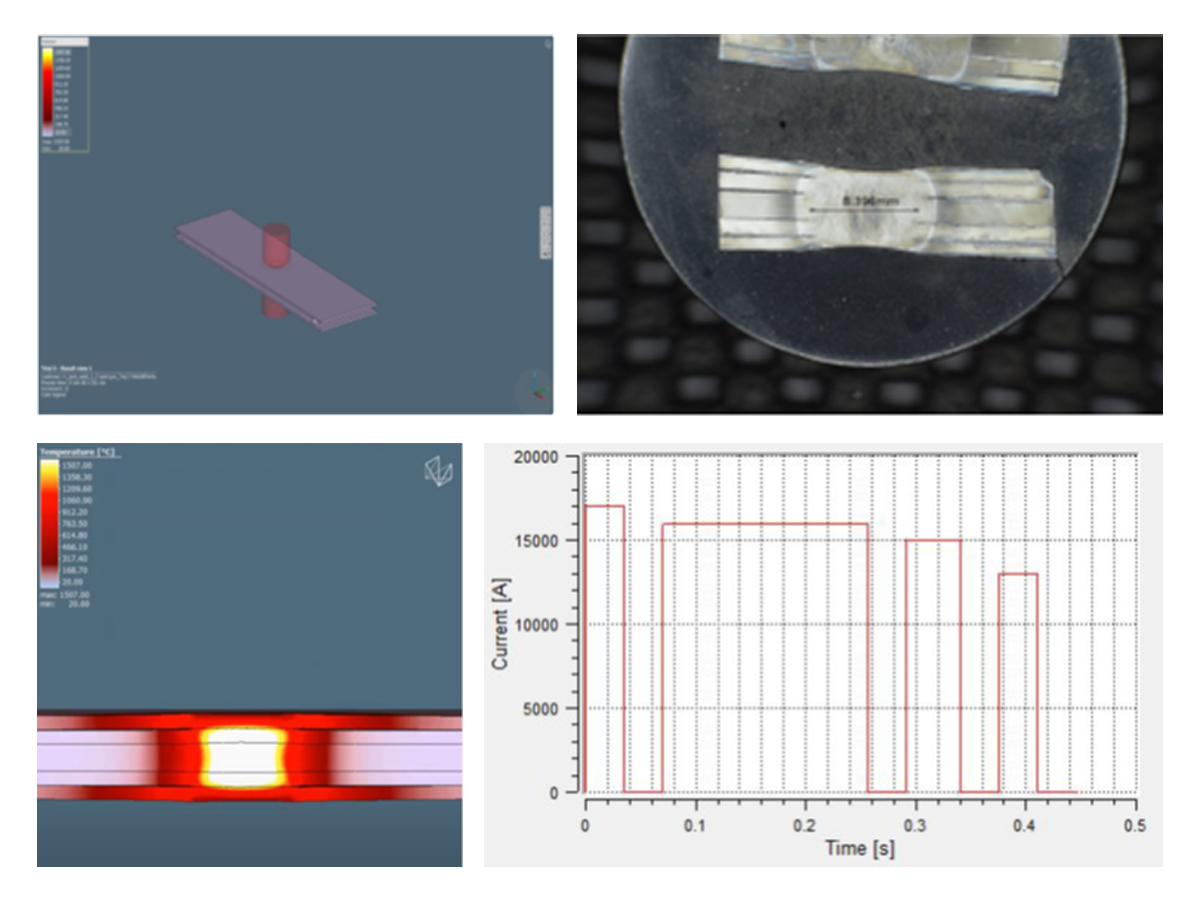

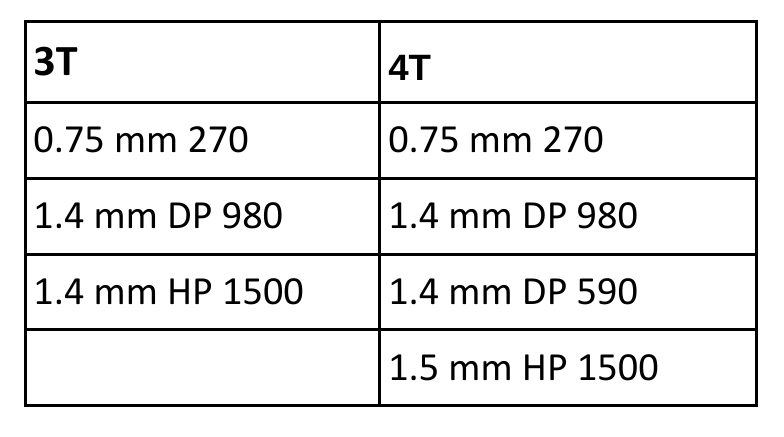

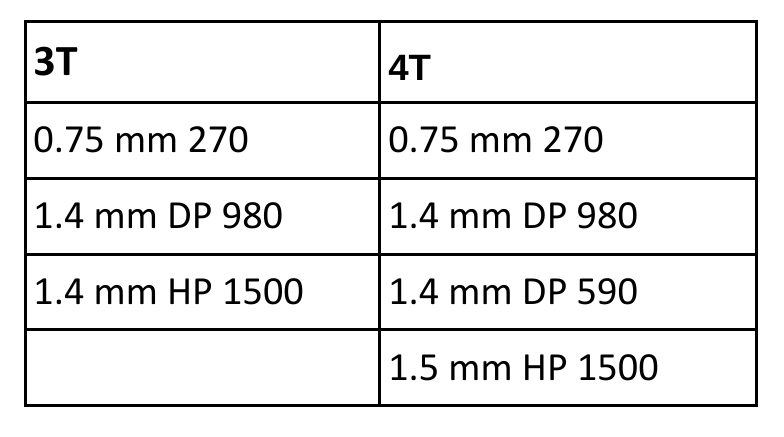

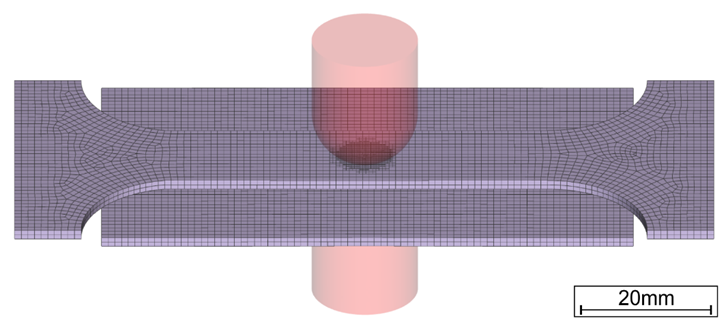

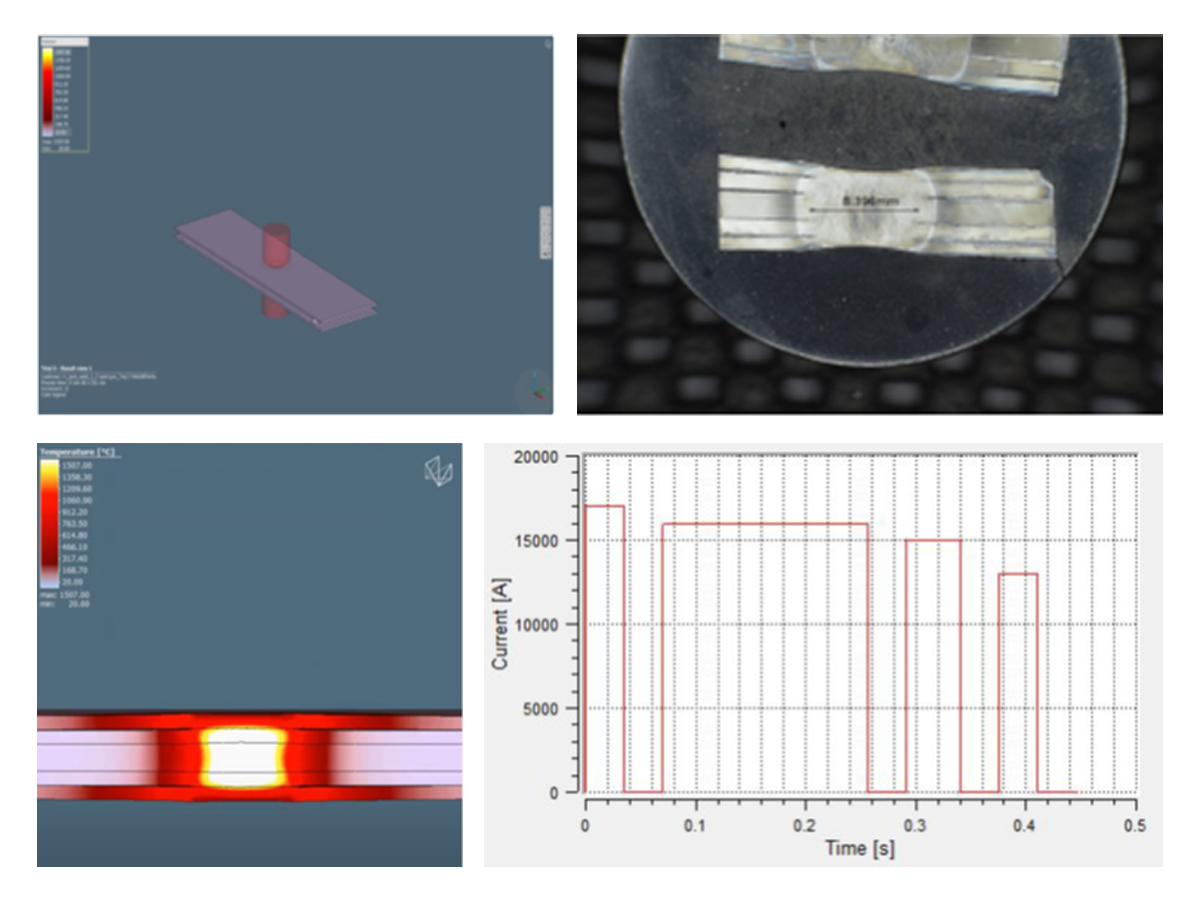

To establish initial welding parameters simulations were conducted using the Simufact software by Hexagon. As shown in Figure 2, the final setup included a set of welding electrodes that clamped the 5-layer AHSS stack-up. Several simulations were created with a designated set of welding parameters of current, time, number of pulses, and electrode force.

Figure 2. Example of simulation and experimental results showing acceptable 5T resistance spot weld (Meets AWS Automotive specifications)

Thanks is given to Menachem Kimchi, Associate Professor-Practice, Dept of Materials Science, Ohio State University and Technical Editor – Joining, AHSS Application Guidelines, for this article.

Automotive Welding Process Comparison, Blog, Joining

Car body-in-white (BIW) structures, such as pillars and rails, are increasingly made of complex stack-ups of advanced high-strength steels (AHSS) for vehicle lightweighting to achieve improved fuel efficiency and crashworthiness. Complex stack-ups comprise more than two sheets with similar/dissimilar steels and non-equal sheet thicknesses.

Resistance spot welding (RSW) of complex stack-ups can be challenging, especially when a thin sheet of low-strength steel is attached to multiple thick AHSS sheets with a thickness ratio of five or higher (thickness ratio = total thickness of the stack-up/thickness of the thinnest sheet). In such a case, the heat loss is much faster on the thin sheet side than on the thick sheet side, and consequently, obtaining sufficient penetration into the thin sheet without expulsion on the thick sheet side can be challenging.

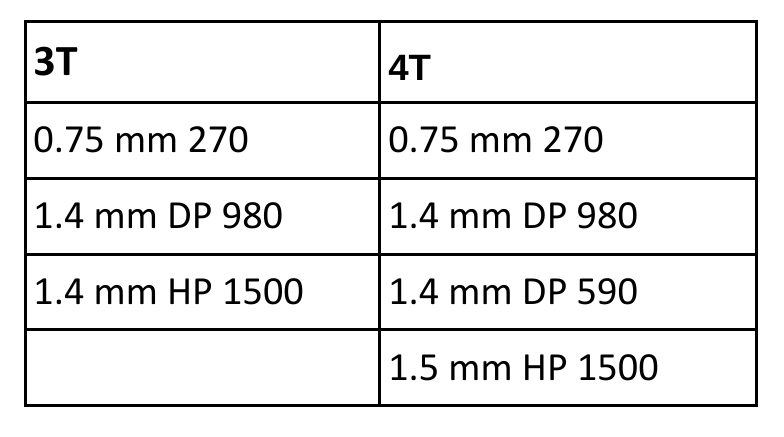

An example of two automotive applications involving complex AHSS steel stack-ups is shown below.

Examples of automotive applications involving complex AHSS steel stack-ups

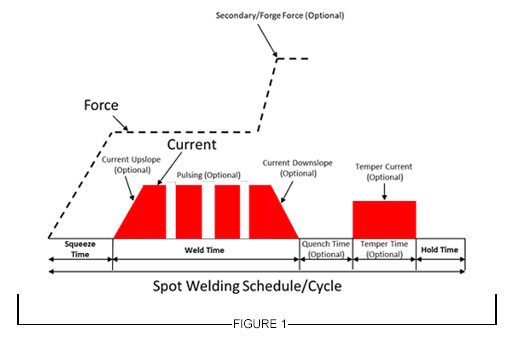

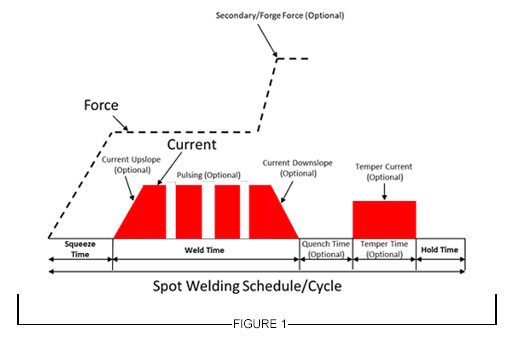

For welding 2T steel stack-ups, the weld schedule may be relatively simple and utilize just one current pulse with a specific weld time. However, typical RSW machines and controllers can customize and precisely control each parameter indicated in Figure 1.

Figure 1: General Description of Resistance Spot Welding Schedule

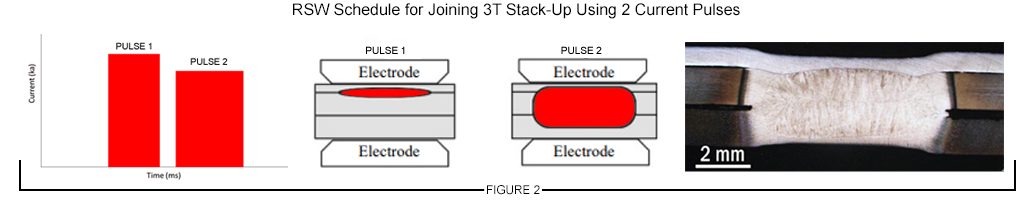

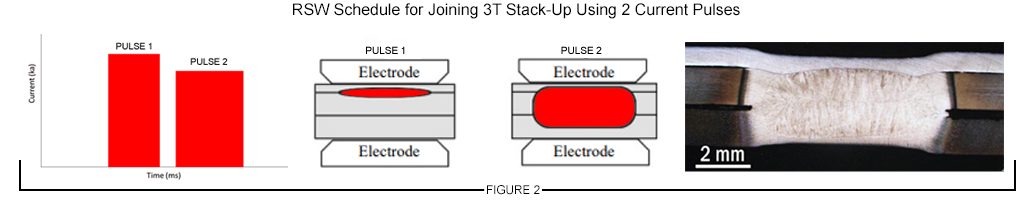

For RSW 3T and 4T applications, more advanced schedules are needed to achieve good weld nugget penetration through all the interfaces in the stack-up. To achieve this objective, the use of multiple current pulses with short cool time in between the pulses showed to be most effective, and in some cases, the application of a secondary force showed to be beneficial.

Figure 2 describes a method for joining the 3T stack-up using two current pulses. The first one is a short-time pulse that does not allow enough time for the electrode cooling to dominate at the top sheet, so a weld can easily form between the top and middle sheet. Once that nugget has formed, the second pulse utilizes a lower current and longer time to form the second nugget, which then grows into the first nugget to form a single weld.

This approach can be also used with electrode force variation during the welding cycle to provide additional control of the contact resistances, but of course, it is limited to machines that are capable of varying force during the weld cycle.

Typical pulse times are 50 – 350 ms with cool times of 20 – 35 ms and current levels between 8 – 15 KA, depending on materials type and thickness.

Figure 2: Example of RSW Schedule for Joining 3T Stack-Up Using 2 Current Pulses

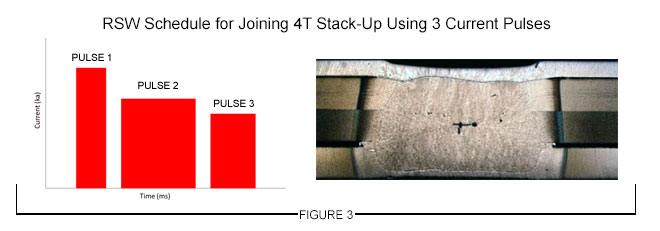

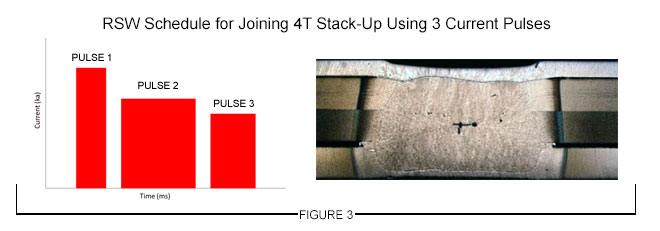

A 4T stack-up example is shown in Figure 3. In this case, a similar approach was used with three current pulses applied during the weld cycle to produce a weld through all interfaces.

The common theme in resistance spot welding all complex stack-ups is using a complex, multi-pulse weld cycle. These more complex schedules should be developed experimentally and potentially with computational modeling. Another consideration that may be beneficial in some cases is to vary the top and bottom electrode face diameter, such as that the smaller electrode face is on the thinner material side of the stack-up.

Figure 3: Example of an RSW Schedule for Joining 4T Stack-Up Using 3 Current Pulses

Thanks is given to Menachem Kimchi, Associate Professor-Practice, Dept of Materials Science, Ohio State University and Technical Editor – Joining, AHSS Application Guidelines, for this article.

Resistance Welding Steel to Aluminium

This article summarizes a paper entitled, “Process, Microstructure and Fracture Mode of Thick Stack-Ups of Aluminum Alloy to AHSS Dissimilar Metal Spot Joints”, by Luke Walker, Colleen Hilla, Menachem Kimchi, and Wei Zhang, Department of Materials Science and Engineering, The Ohio State University.W-9

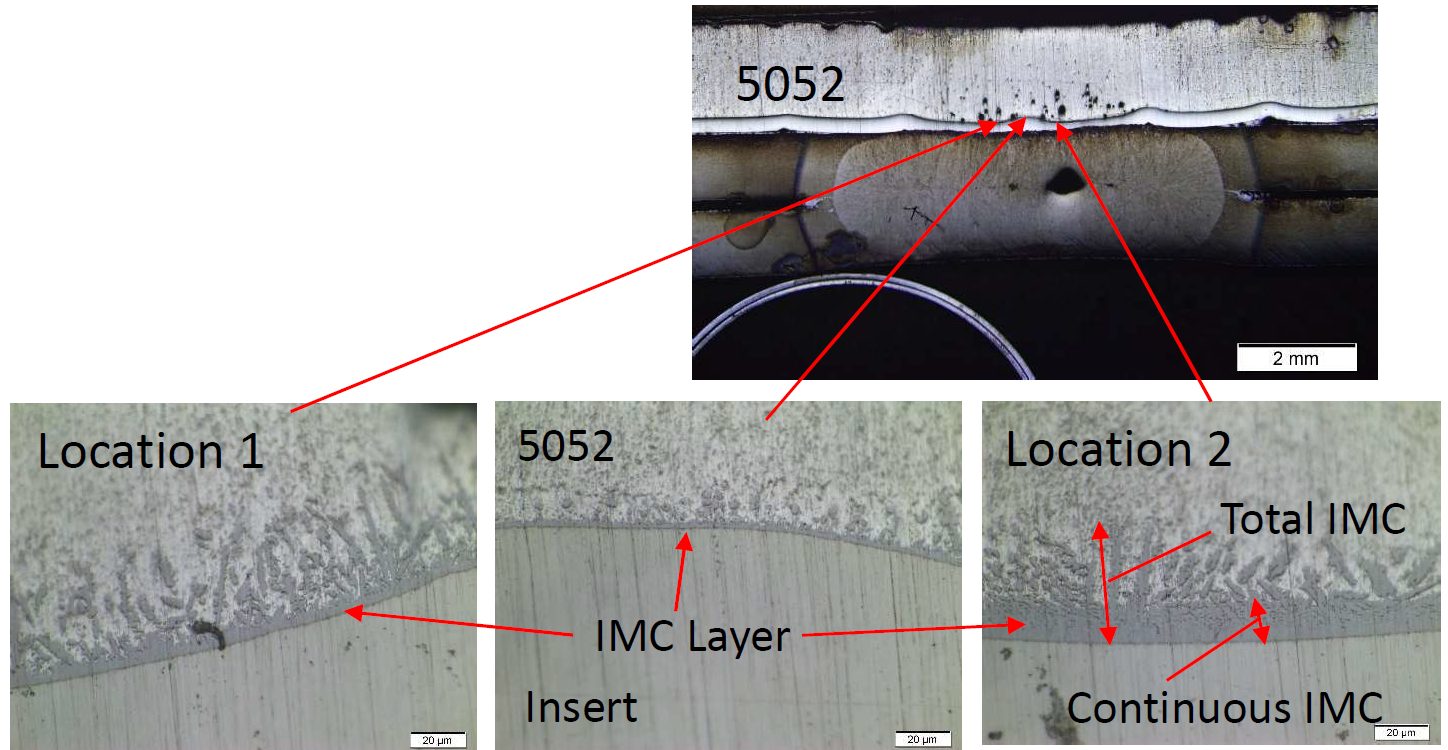

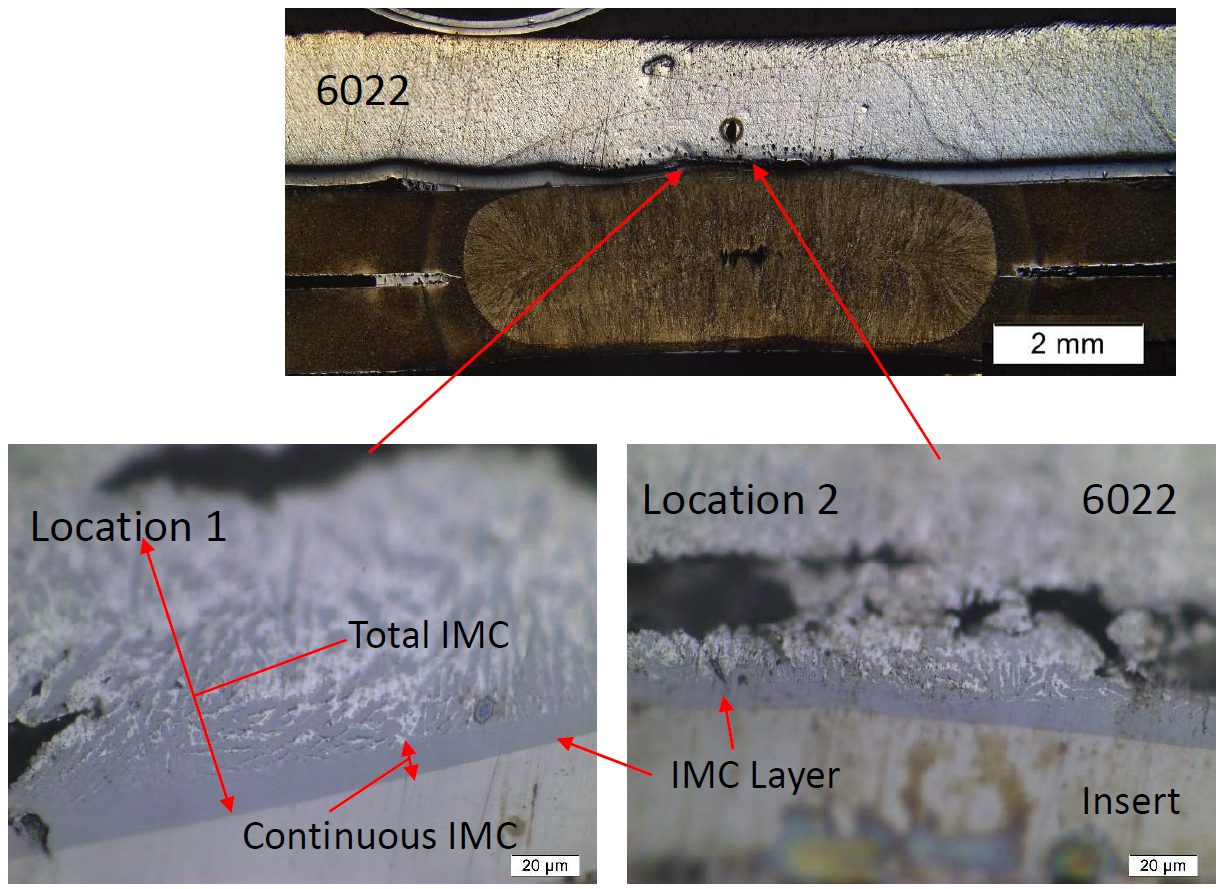

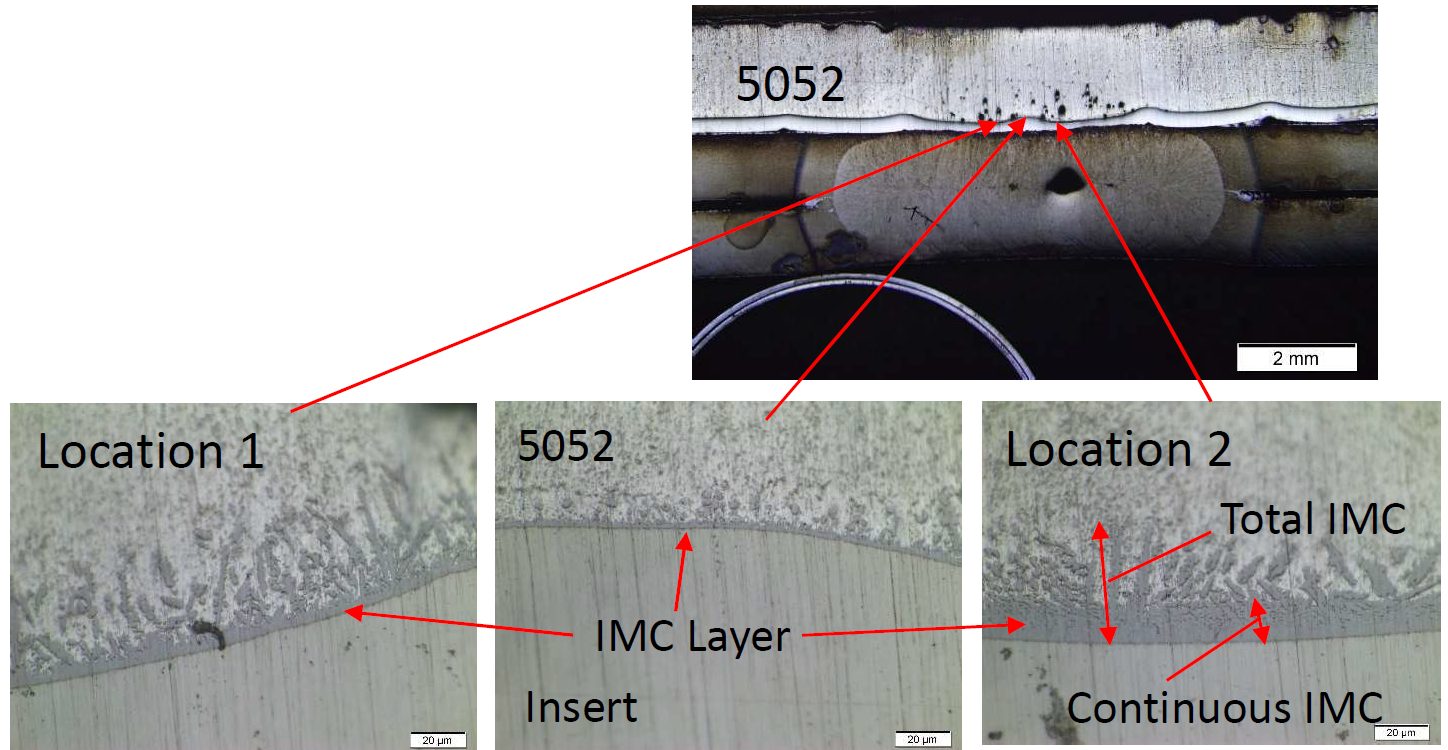

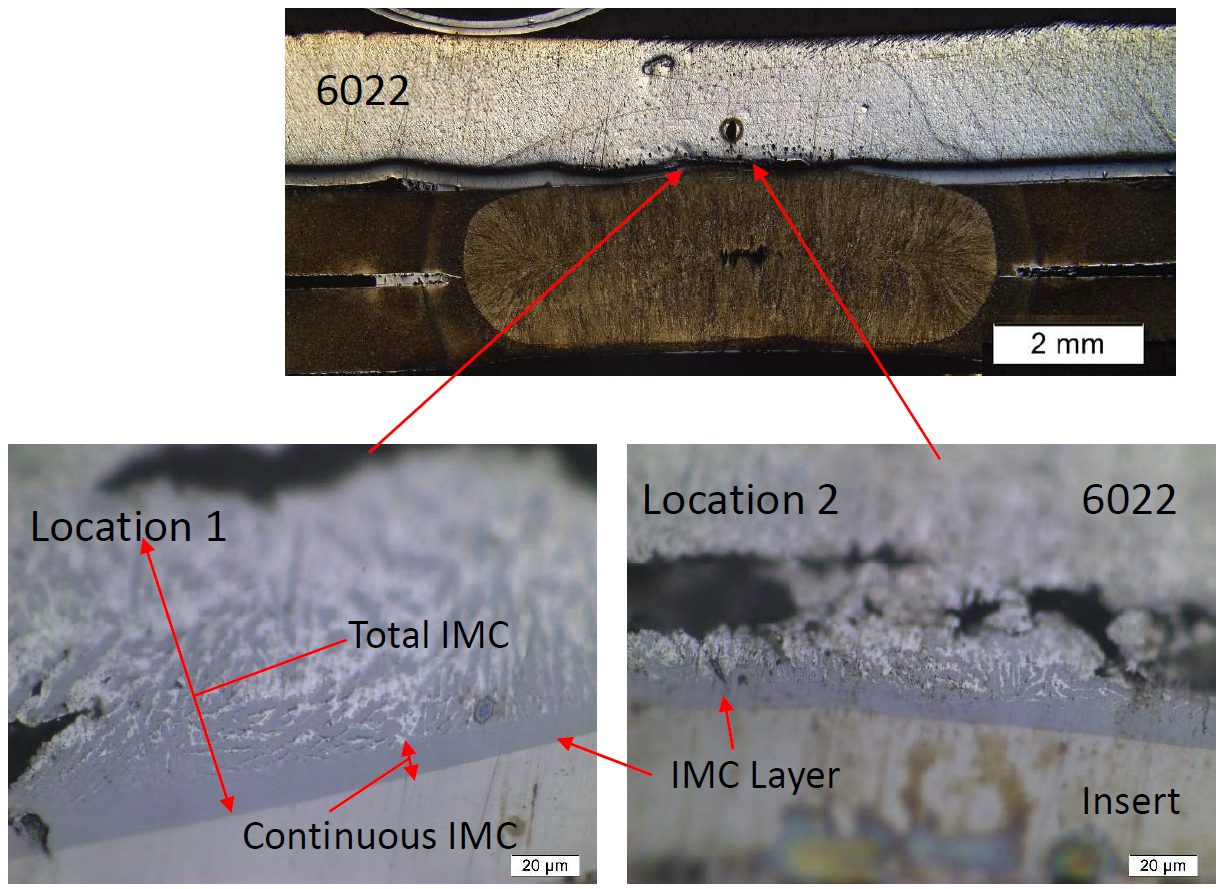

Researchers at The Ohio State University studied the effects of adding a stainless steel (SS) insert to a dissimilar Advanced High-Strength Steel (AHSS) to aluminum (Al) resistance spot weld (RSW). The SS insert was ultrasonically welded to the Al sheet prior to the RSW being performed. The purpose of the SS is to reduce the intermetallic layer that forms when welding steel to aluminum. This process increases the strength and toughness of the weld. In this study, the process is applied to three sheet (3T) stack up that contains one Al sheet and two 1.2 mm thick Press Hardened (PH) 1500 sheets. The joint strength is measured in lap shear testing and the intermetallic thickness/ morphology is studied after cross sectioning the welds.

During the microstructure evaluation it was noted that Al 6022 contained a larger nugget diameter as compared to the Al 5052 welds. A few potential reasons for the hotter welds were proposed including cleanliness of the electrodes, surface oxides, and thickness of the different alloys. The welds on the Al 5052 stack ups were made first on clean electrodes whereas the Al 6022 was made on potentially dirty electrodes that increased the contact resistance. The effects of different surface oxides are not likely given the SS sheet is ultrasonically welded but could still add to the higher heat input in the RSW. The Al 6022 is 0.2 mm thicker, which could increase the bulk resistance and decrease the cooling effect from the electrodes.

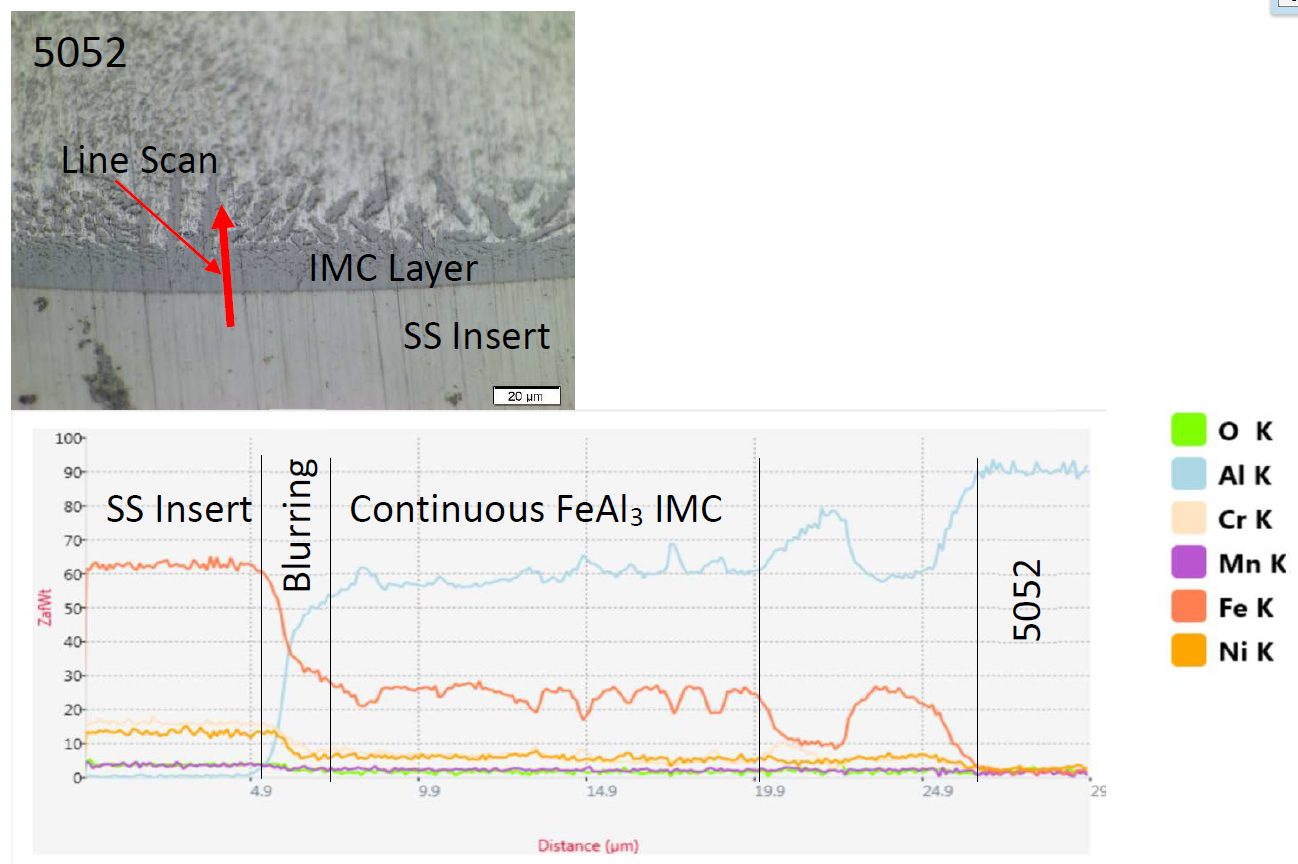

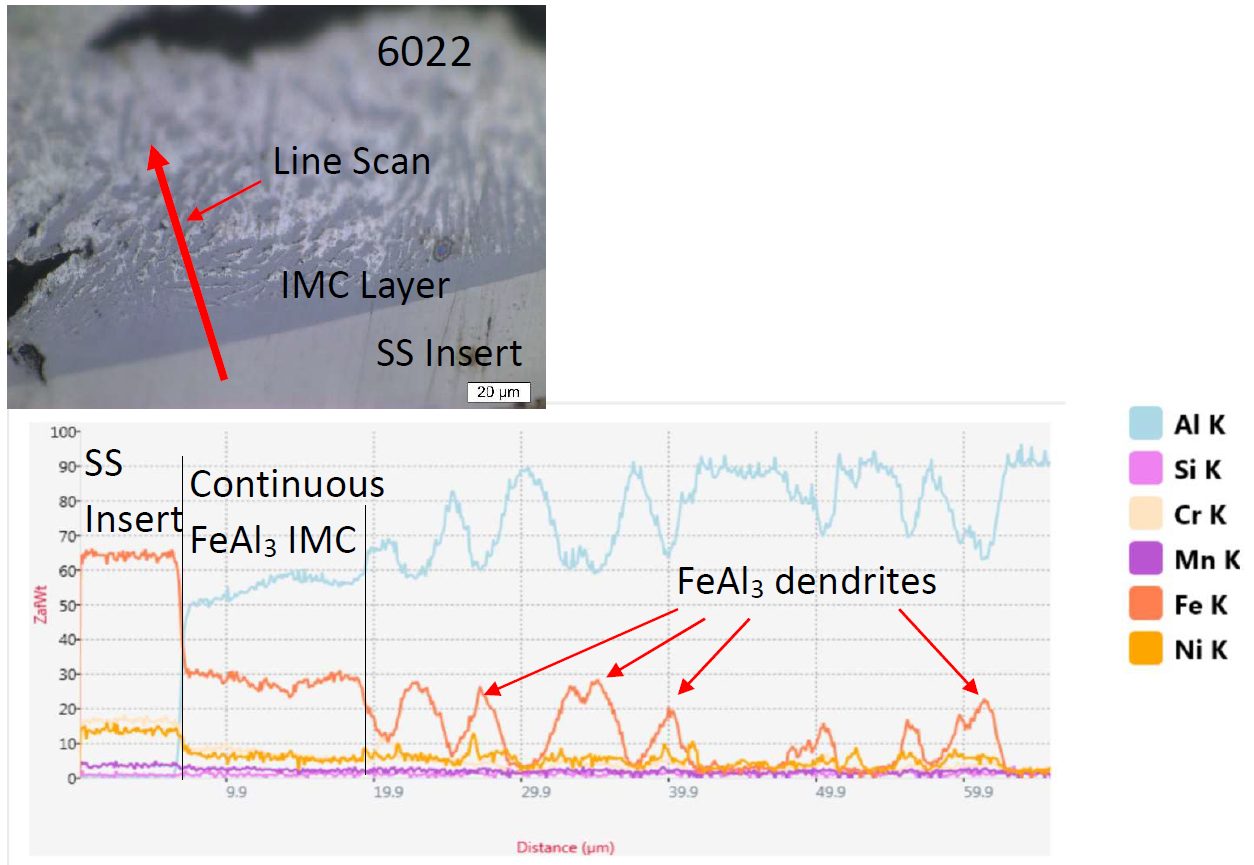

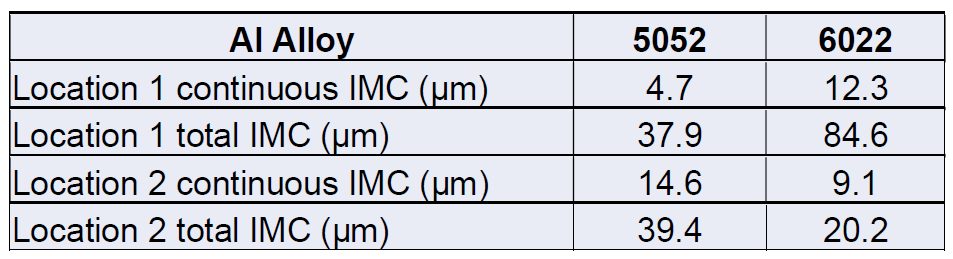

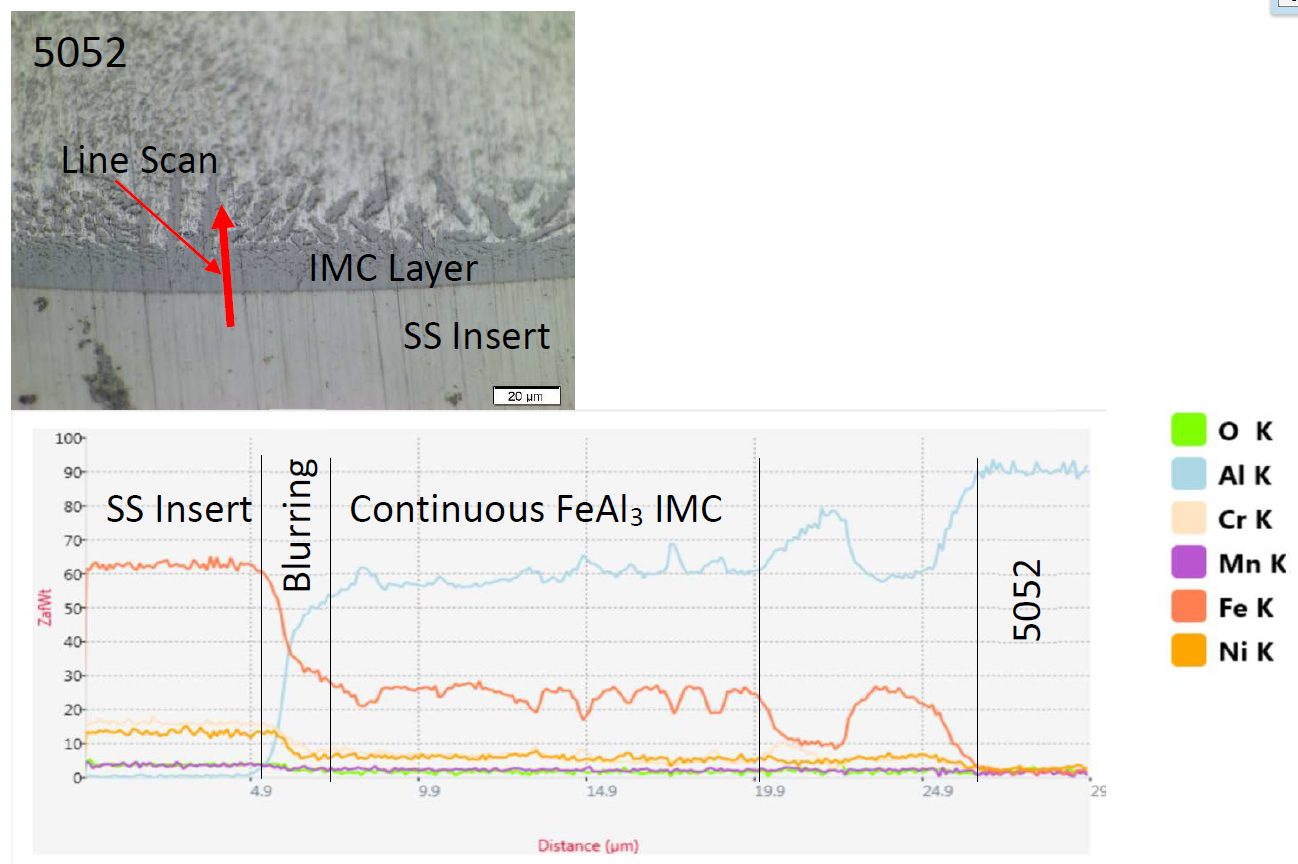

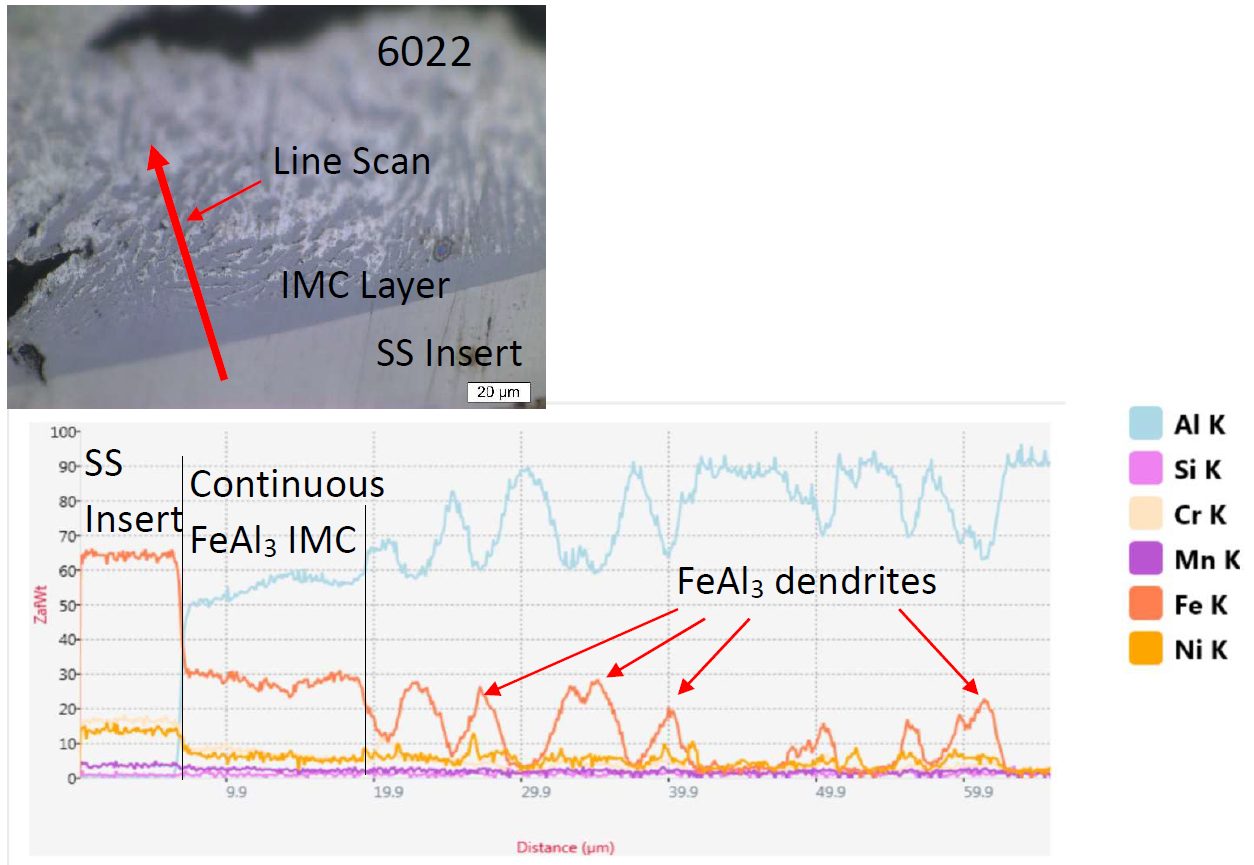

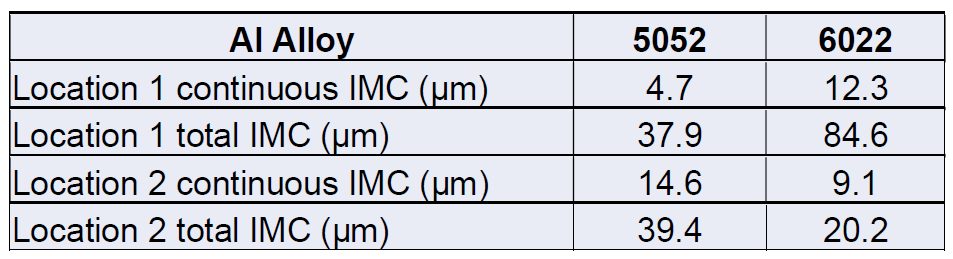

The 3T welds likely had much lower strength and toughness due to cracks that formed at the Al-SS insert interface. These can be attributed to an increase in intermetallic compound (IMC) thickness and the residual stress caused by the forge force. The IMC thickness was measured two ways: The first measurement was of the continuous IMC layer and the second was from the Al-Fe interface to the end of the IMC dendrites (Figure 1, 2 and Table 1). The Al 5052 observed the thickest continuous IMC layer but Al 6022 was close to the Al 5052 thickness. This can be attributed to the increased Si content of Al 6022 which has been shown to decrease the growth of Fe-Al intermetallics.

Figure 1: IMC in the Al Alloy 5052 to Stainless-Steel Weld.W-9

Figure 2: IMC in the Al Alloy 6022 to Stainless-Steel Weld.W-9

Table 1: IMC Thickness of Both the 5052 Weld and the 6022 Weld.W-9

Referencing Figure 3, the 2T stack-up has a higher tensile strength as well as significantly higher fracture energy absorbed compared to the 3T stack-ups. This is mainly attributed to the failure mode observed in the different stack-ups. The 2T welds had button pullout failure while 3T stack-ups had interfacial Failure.

![Figure 3: Failure Load and Fracture Energy [(A) Al to steel (Al-Us) welds and (B) steel to steel (Us-Us) welds (the 2T 6022 results are from previous work(10))]W-9](https://ahssinsights.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/fig4-process.jpg)

Figure 3: Failure Load and Fracture Energy [(A) Al to steel (Al-Us) welds and (B) steel to steel (Us-Us) welds (the 2T 6022 results are from previous work(10))]W-9

The Al 6022 contains higher Si content which likely decreased the growth of the continuous IMC layer but not the overall IMC layer (as seen in Figure 4 and Figure 5) due to higher weld temperatures. The joint strength of the welds in the 3T stack-ups were closer to the expected weld strength unless there was expulsion that caused a 5-kN drop in strength.

Figure 4: EDS Line Scan of the IMC in Location 2 on the 5052 3T Sample (SS stands for austenitic stainless steel 316).W-9

Figure 5: EDS Line Scan of the Intermetallic Layer at Location 1 on the 6022 3T Sample (SS stands for austenitic stainless steel 316).W-9

Laser Welding

This article summarizes the findings of a paper entitled, “Hot cracking investigation during laser welding of high-strength steels with multi-scale modelling approach”, by H. Gao, G. Agarwal, M. Amirthalingam, M. J. M. Hermans.G-4

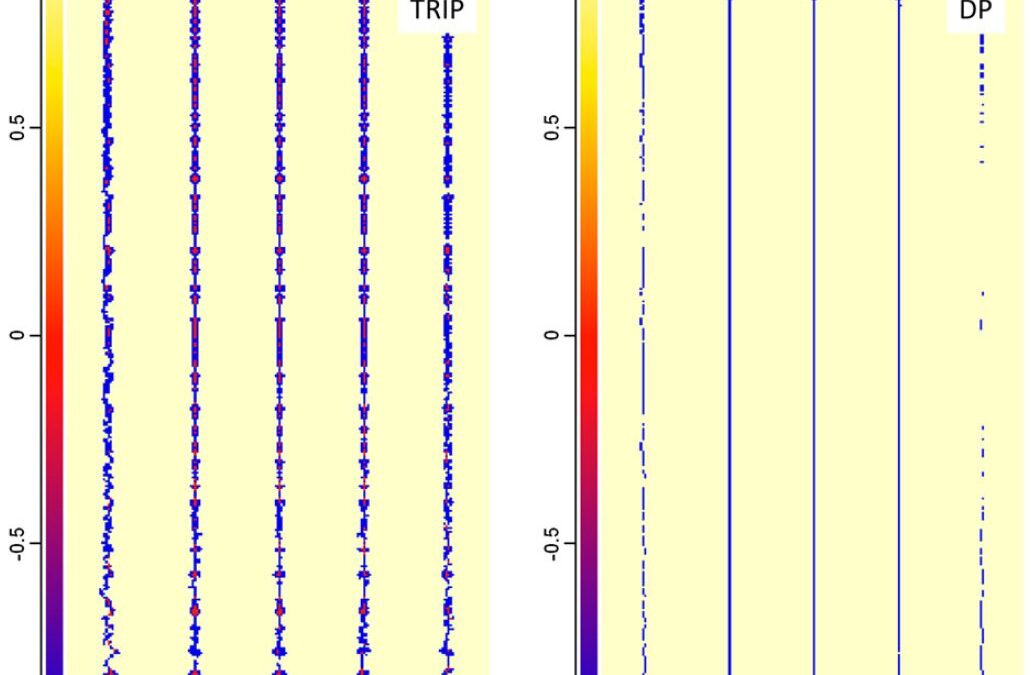

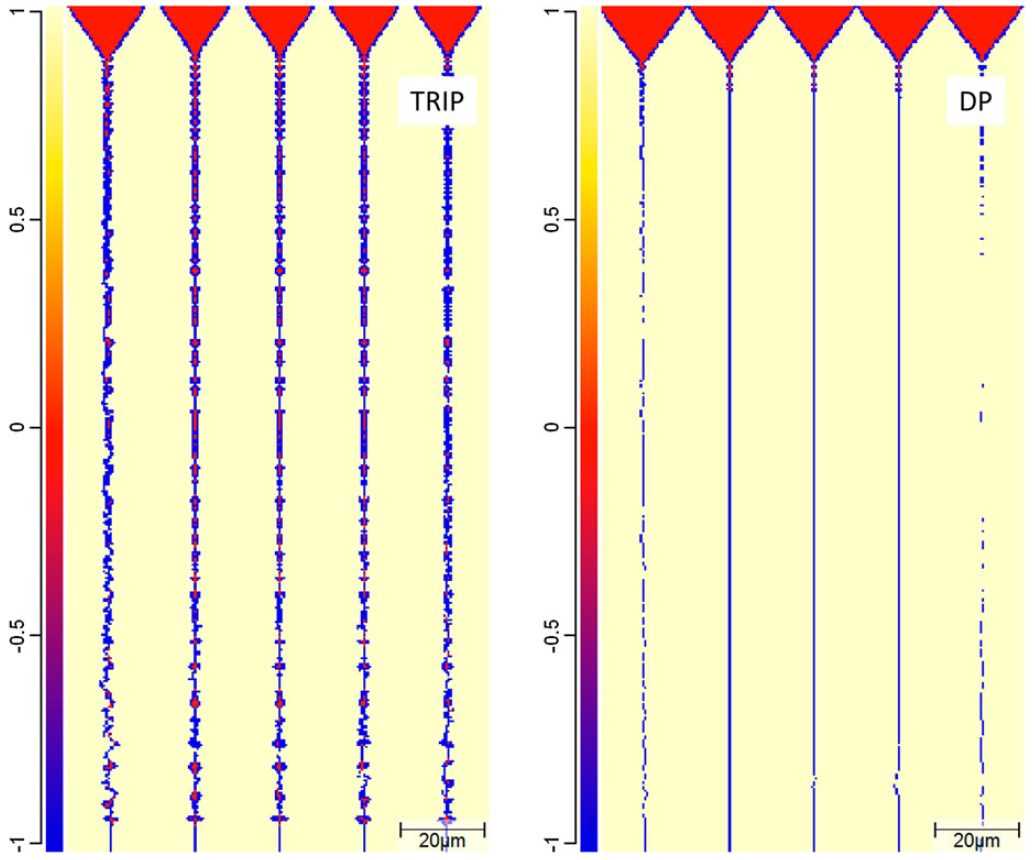

Researchers at Delft University of Technology (TU Delft) in The Netherlands and Indian Institute of Technology Madras in India attempted to model Hot Cracking susceptibility in TRIP and DP steels. For this experiment, TRIP and DP steels are laser welded and the temperatures experienced are recorded with thermocouples at three positions. Temperatures experienced during welding are measured and used to validate a finite element model which is then used to extract the thermal gradient and cooling rate to be used as boundary conditions in a phase field model. The phase field model is used to simulate microstructural evolution during welding and specifically during solidification. The simulation and experimental data had good agreement with max temperature deviation below 4%.

Summary

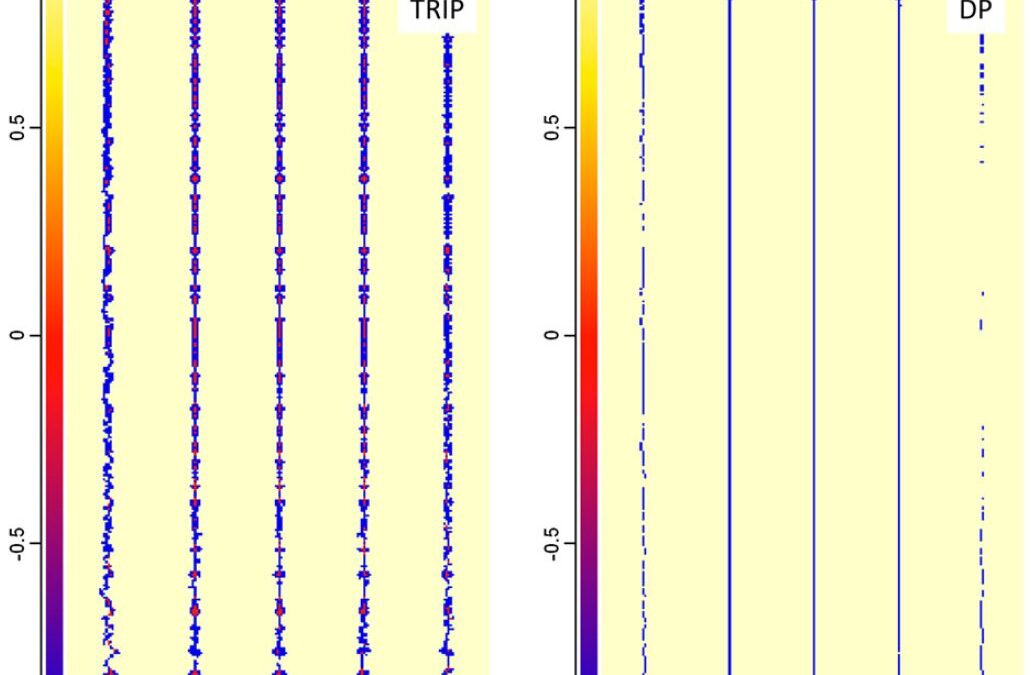

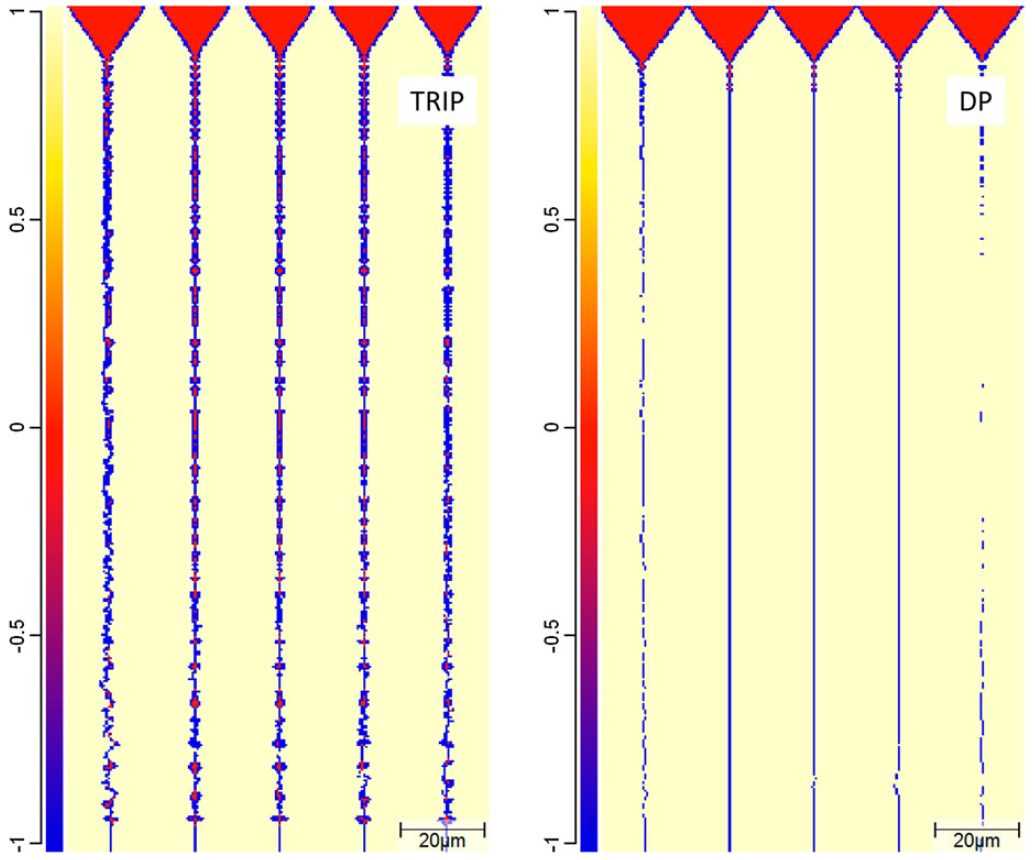

Referencing Figure 1 (Figure 6 in the original paper) which shows the microstructure where the dendritic tips meet the wel, centerline, it is observed that TRIP steels reach a solid fraction of 93.7% and DP steels reach a solid fraction of 96.3% meaning that TRIP steels have a larger solidification range than the DP steels. Figure 8 shows the phosphorus distribution where the dendritic tips reach the weld centerline. TRIP steels show a concentration of up to 0.55 wt-% where segregation occurs compared to the original composition of 0.089 wt-%. DP steels show a max of 0.06 wt-% which is significantly lower than the TRIP steels. In addition to phosphorus, Al is seen in high concentration in TRIP steels which contributes to the broder solidification range. A pressure drop is the last factor contributing to the Hot Cracking observed in TRIP steels(figure 2). The pressure drop is due to a lack of extra liquid feeding in the channels and forms a pressure difference from the dendrite tip to root. The pressure drop in TRIP steels is calculates to 941.2 kPa and 10.2 kPa in DP steels. The combination of element segregation, pressure drop, and thermal tensile stresses induced during laser welding results in a higher Hot Cracking susceptibility in TRIP steels as compared to DP steels.

Figure 1: Phase distributions in the TRIP and the DP steel when the dendritic tips reach the weld centreline.G-4

Arc Welding

This is a summary of a paper of the same title, authored by K. Májlinger, E. Kalácska, and P. Russo Spena, used by permission.M-65

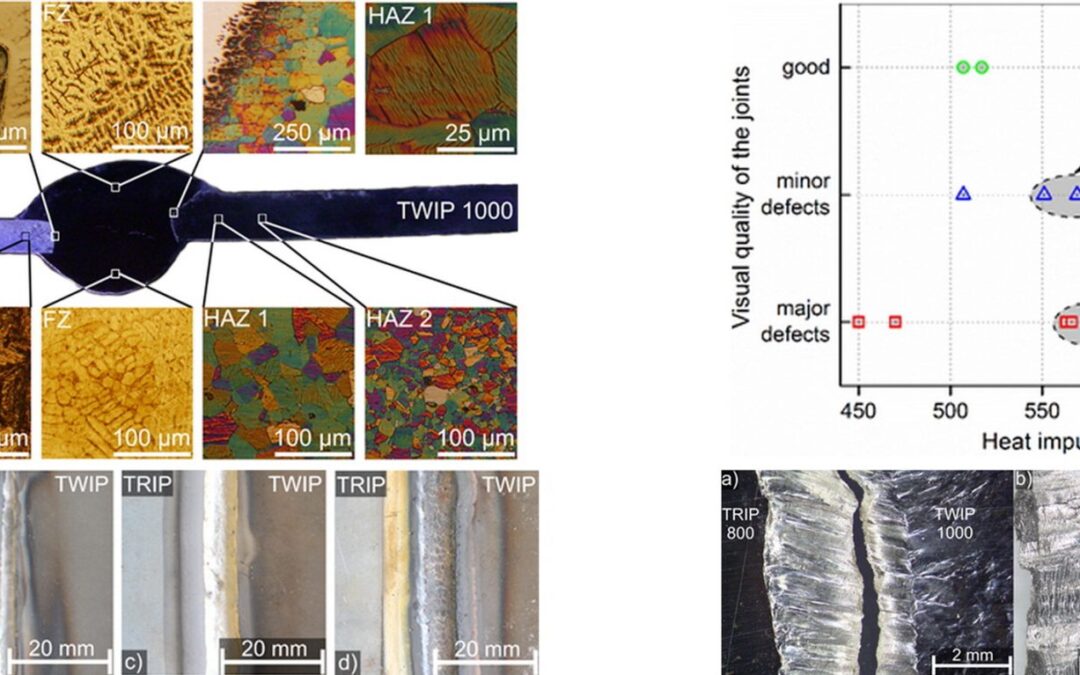

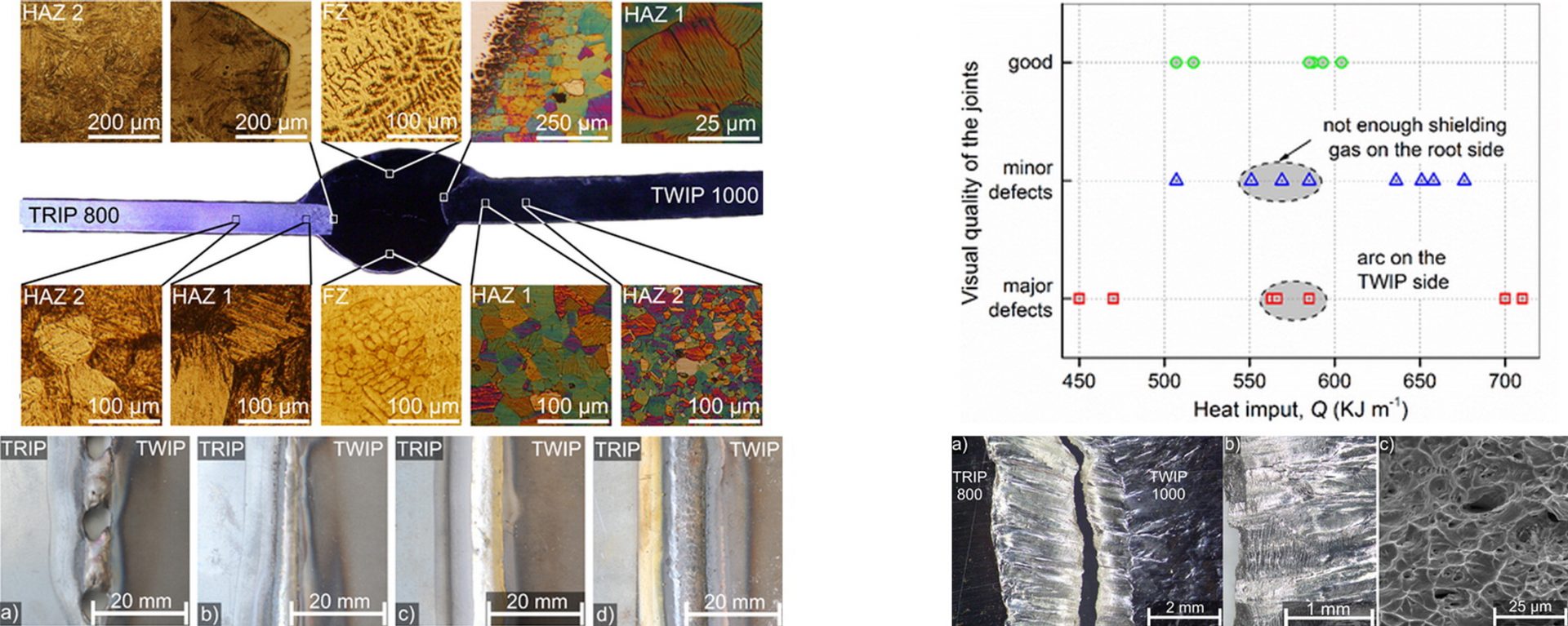

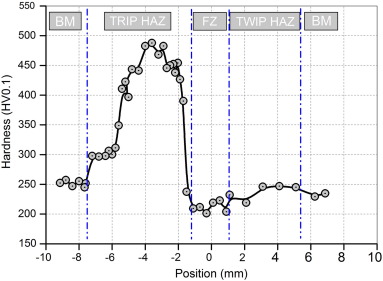

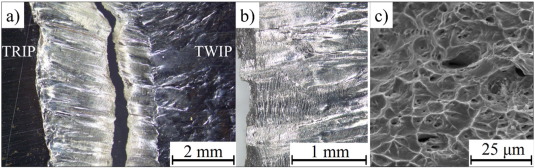

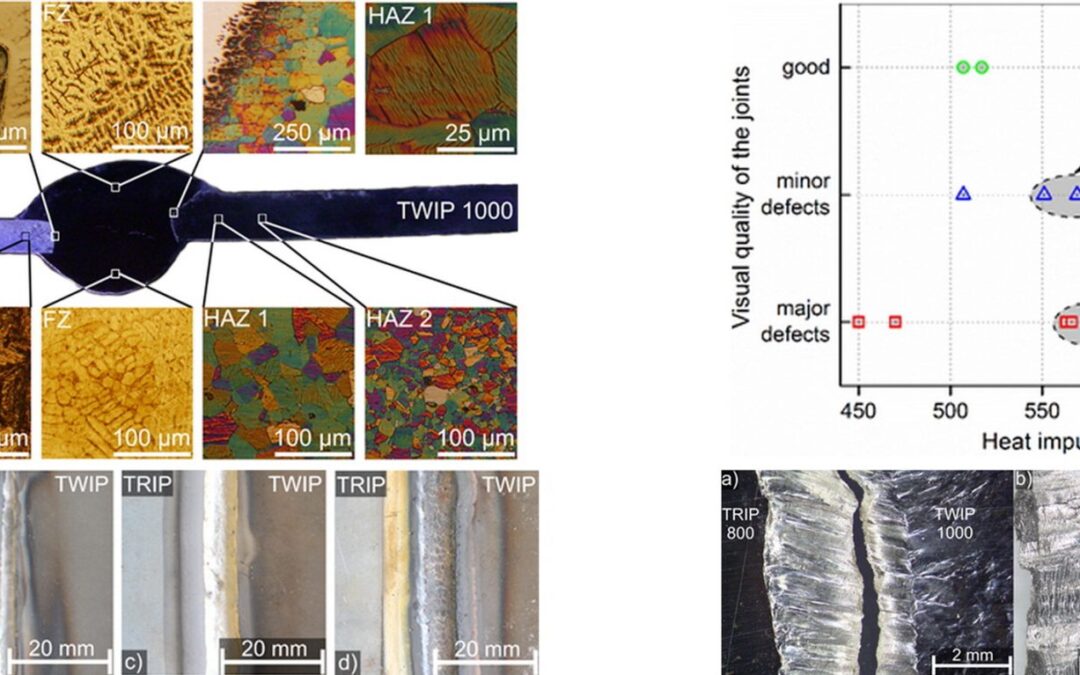

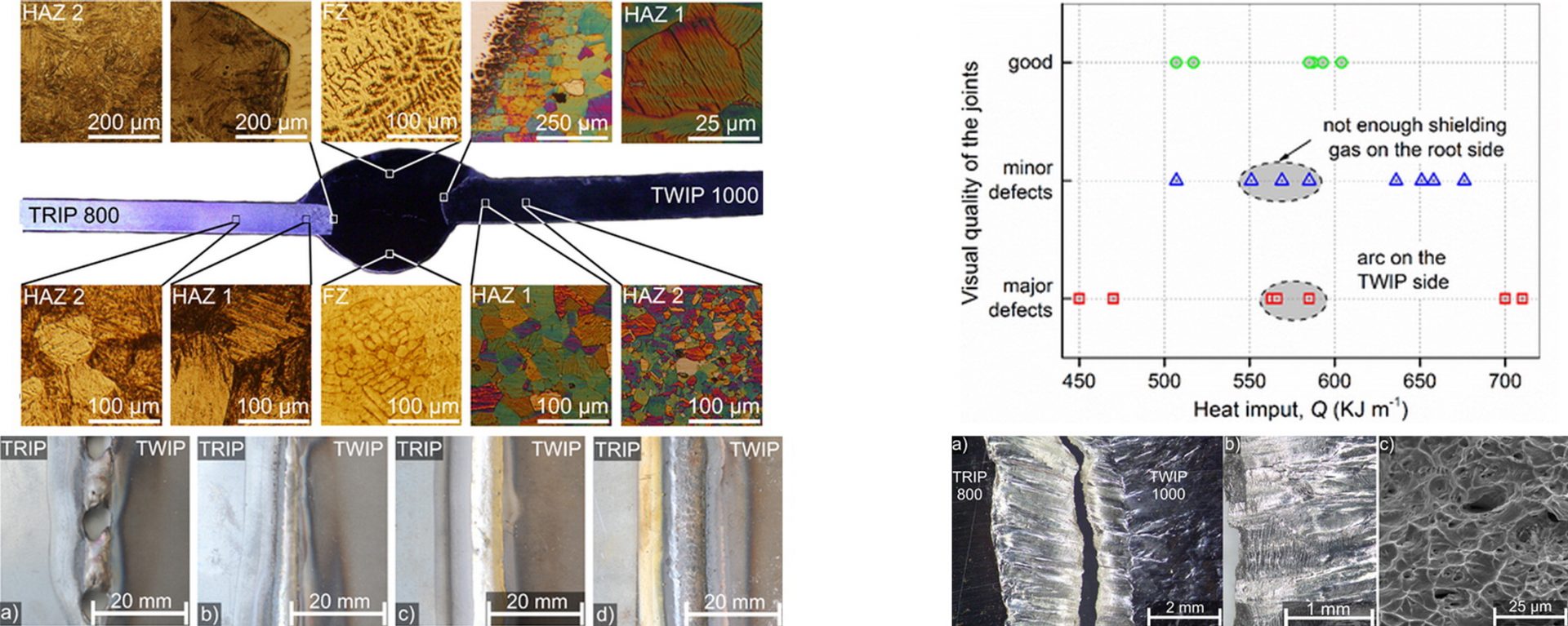

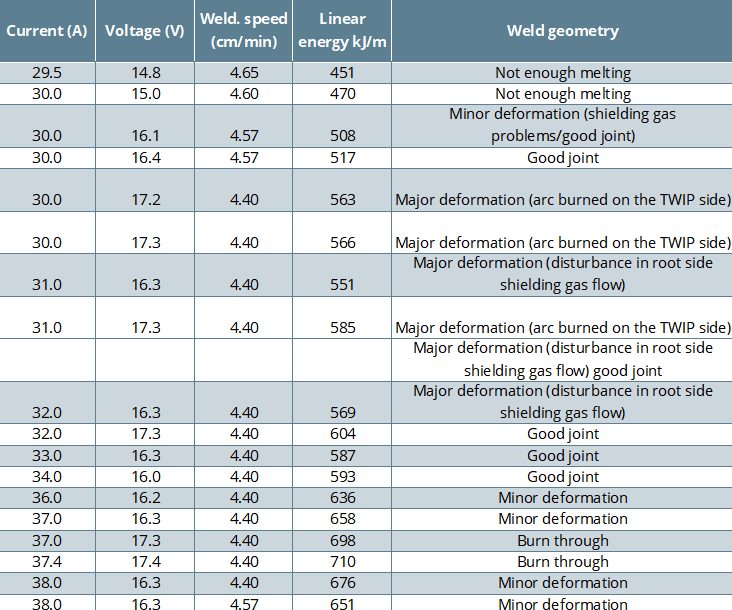

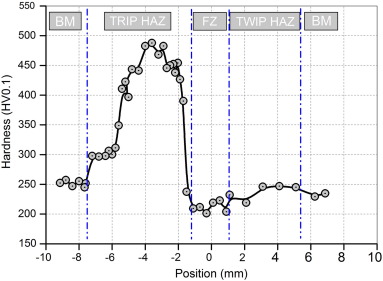

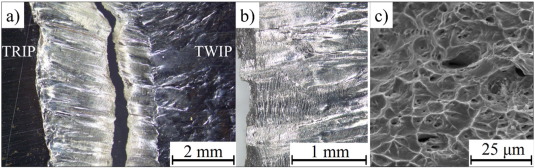

Researchers at the Budapest University of Technology and Economics and the Free University of Bozen-Bolzano tested gas metal arc welding (GMAW) of dissimilar Advanced High-Strength Steel (AHSS) sheets.M-65 The test pieces were 100 x 50 mm samples of 1.4 mm TWIP (TWIP1000) and 0.9 mm TRIP (HCTC800T) sheet steels were welded in a lap joint configuration with 0.8 mm diameter AWS ER307Si austenitic stainless steel wire to determine appropriate GMAW parameters for good quality welds. Quality was determined by external appearance, microstructure, and mechanical properties. Good welds were achieved with linear heat inputs (Q) with ranges from 500-650 kJ/m. The only fractures that occurred appeared within the weld bead by ductile failure modes. The HAZ of the TWIP steel showed grain coarsening and the HAZ of the TRIP steel experienced microstructural changes relative to the distance from the fusion boundary. The ultimate tensile strength (UTS) varies between 73%-84% of the weaker of the two steels.

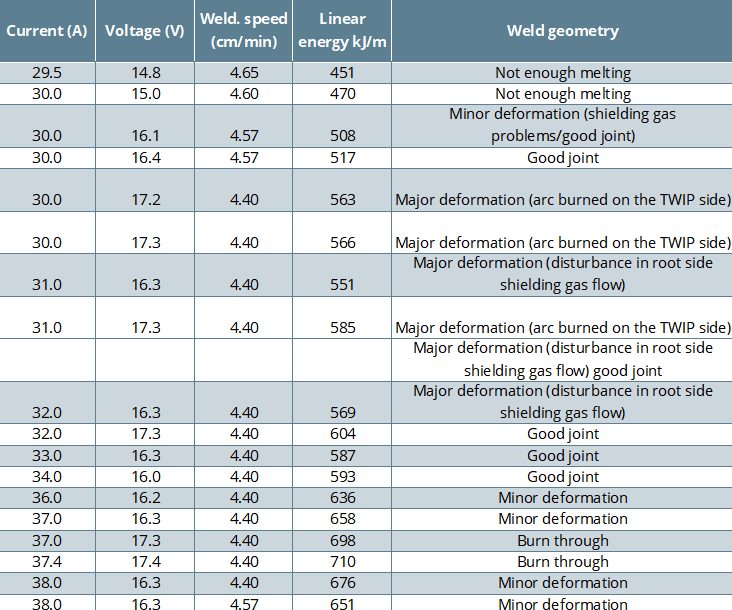

Welding was conducted with an automated linear drive system with pure Argon (99.996% Ar) shielding gas at 10L/min. Wire feed rates were approximately 3.5 m/min with Direct Current Electrode Positive (DCEP) polarity. Changes in current, voltage, weld speed, and the resulting linear energy are compared in Table 1.

Figure 1: Overview of Dissimilar AHSS GMAW Welding.M-65

Table 1: Results of the preliminary welding tests in terms of TWIP-TRIP joint quality.M-65

After welding, transverse sections were cut from the welds and etched to show the microstructure. Vickers hardness testing was conducted on the weld samples based on the ASTM E384 standard. Tensile tests were performed on the samples according to the EN ISO 6892-1 standard. Tests were also conducted on unwelded TWIP and TRIP steels for comparison. Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) examinations were made of fracture surfaces to determine failure modes and examine for microscopic weld defects.

The study concluded that dissimilar welds between AHSS steels with the GMAW process can be achieved with consistent results desired for automotive applications.

Figure 2: Vickers Hardness Across Weldment.M-65

Figure 3: Ductile Failure in the fragile zones (FZ).M-65

Blog, RSW Modelling and Performance

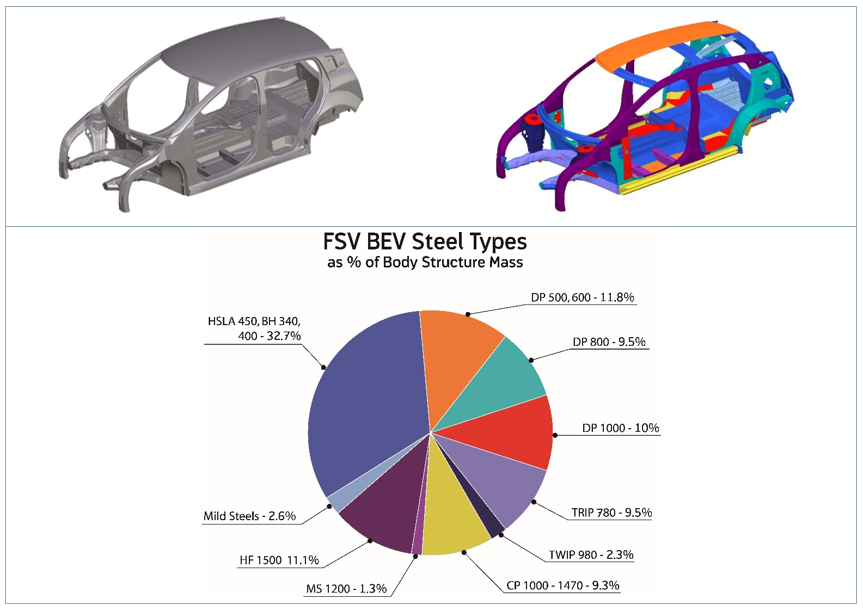

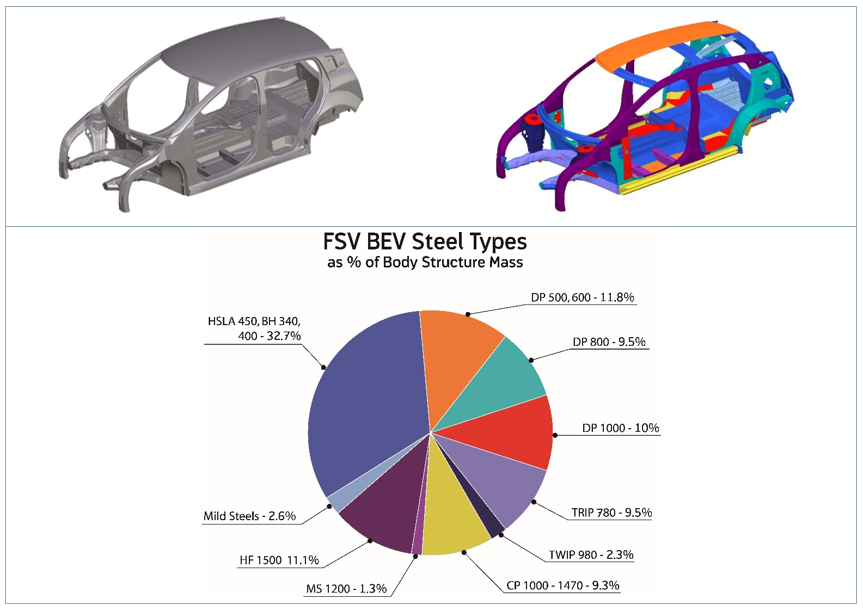

Modern car bodies today are made of increasing volumes of Advanced High-Strength Steels (AHSS), the superb performance of which facilitates lightweighting concepts (see Figure 1). To join the different parts of a car body and create the crash structure, the components are usually welded to achieve a reliable connection. The most prominent welding process in automotive production is resistance spot welding. It is known for its great robustness, and easily applicable in fully automated production lines.

Figure 1: AHSS Content in Modern Car Body.W-7

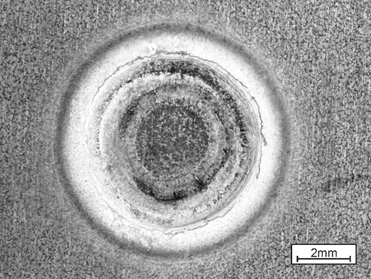

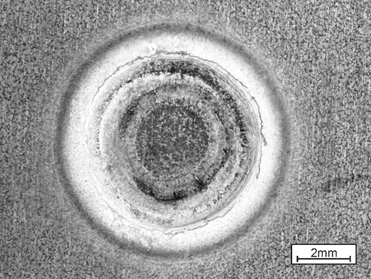

There are, however, challenges to be met to guarantee a high-quality joint when the boundary conditions change, for example, when new material grades are introduced. Interaction of a liquefied zinc coating and a steel substrate can lead to small surface cracks during resistance spot welding of current AHSS, as shown in Figure 2. This so-called liquid metal embrittlement (LME) cracking is mainly governed by grain boundary penetration with zinc, and tensile stresses. The latter may be induced by various sources during the manufacturing process, especially under ‘rough’ industrial conditions. But currently, there is a lack of knowledge, regarding what is ‘rough’, and what conditions may still be tolerable.

Figure 2: Top View of LME-Afflicted Spot Weld.

The material-specific amount of tensile stresses necessary for LME enforcement can be determined by the experimental procedure ‘welding under external load’. The idea of this method, which is commonly used for comparing cracking susceptibilities of different materials to each other, is to apply increasing levels of tensile stresses to a sample during the welding process and monitor the reaction. Figure 3 shows the corresponding experimental setup.

Figure 3: Welding under external load setup.L-51

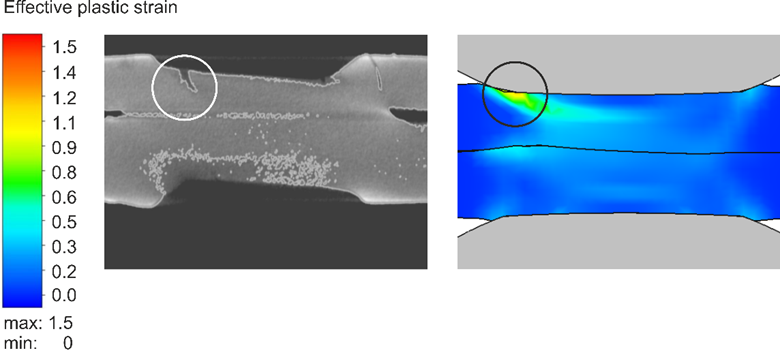

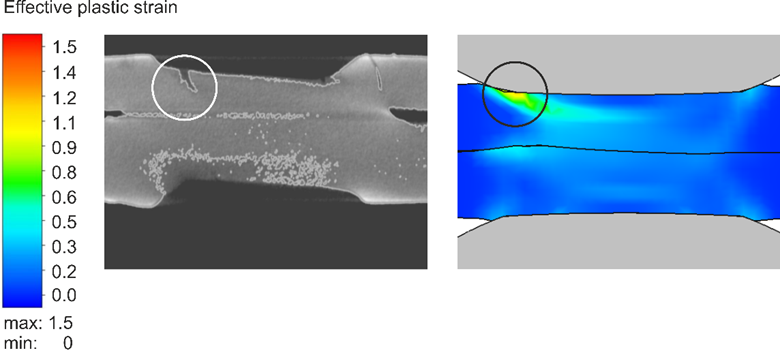

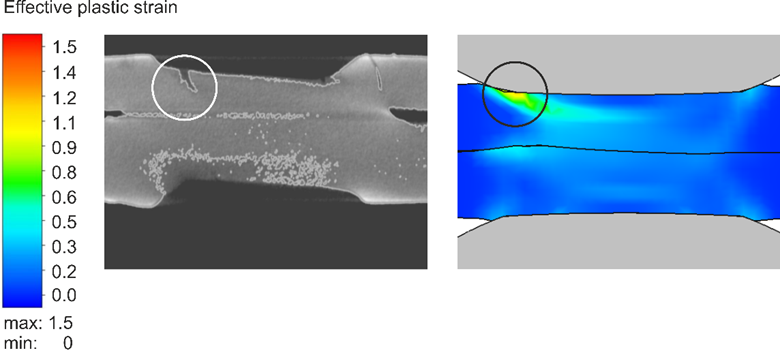

However, the known externally applied stresses are not exclusively responsible for LME, but also the welding process itself, which puts both thermally and mechanically induced stresses/strains on the sample. Here, the conventional measuring techniques fail. A numerical reproduction of the experiment grants access to the temperature, stress and strain fields present during the procedure, providing insights on the formation of LME. The electro-thermomechanical simulation model is described in detail in Modelling RSW of AHSS. It is used to simulate the welding under external load procedure (see Figure 4).

Figure 4: Simulation Model of Welding Under External Load.

The videos that can be found in the link above show the corresponding temperature and plastic strain fields. As heat dissipates quickly through the water-cooled electrode, a temperature gradient towards the adjacent areas and a local temperature maximum on the surface forms. The plastic strains accumulate mainly at the electrode indentation area. The simulated strain field shows a local maximum of plastic deformation at the left edge of the electrode indentation, amplified by the externally applied stresses and the boundary conditions implied by the procedure. This area correlates with experimentally observed LME cracking sites and paths as shown in Figure 5.

The simulation shows that significant plastic strains are present during welding. When external stresses (in reality e.g. due to poor part fit-up or distorted parts) contribute to the already high load, LME cracking becomes more likely. The numerical simulation model facilitates the determination of material-specific safety limits regarding LME cracking. Parameter variations and their effects on the LME susceptibility can easily be investigated by use of the model, enabling the user to develop strict processing protocols to reduce the likelihood of LME. Finally, these experimental procedures can be adapted to other high-strength materials, to aid their application understanding and industrial set-up conditions.

Figure 5: LME Cracks in Cross Section View at Highly Strained Locations.

For more information on this topic, see the paper, co-authored by Fraunhofer and LWF Paderborn, documented in Citation F-23. You may also download the full report documenting the WorldAutoSteel LME project for which this work was conducted.

![Figure 3: Failure Load and Fracture Energy [(A) Al to steel (Al-Us) welds and (B) steel to steel (Us-Us) welds (the 2T 6022 results are from previous work(10))]W-9](https://ahssinsights.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/fig4-process.jpg)