Citations

Citations:

X-4. D. Xu, L. Shi, and H. Xiao, “Mechanism investigation and strategies for reducing residual stress at open ends of the roll-formed part,” Baosteel Technical Research, Volume 17, Number 3, September 2023, Page 25; Available from doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.1674-3458.2023.03.004

![Considerations When Deciding Whether to Cold Form or Hot Form]()

Automakers contemplating whether a part is cold stamped or hot formed must consider numerous ramifications impacting multiple departments. The considerations below relative to cold stamping are applicable to any forming operation occurring at room temperature such as roll forming, hydroforming, or conventional stamping. Similarly, hot stamping refers to any set of operations using Press Hardening Steels (or Press Quenched Steels), including those that are roll formed or fluid-formed.

Equipment

There is a well-established infrastructure for cold stamping. New grades benefit from servo presses, especially for those grades where press force and press energy must be considered. Larger press beds may be necessary to accommodate larger parts. As long as these factors are considered, the existing infrastructure is likely sufficient.

Progressive-die presses have tonnage ratings commonly in the range of 630 to 1250 tons at relatively high stroke rates. Transfer presses, typically ranging from 800 to 2500 tons, operate at relatively lower stroke rates. Power requirements can vary between 75 kW (630 tons) to 350 kW (2500 tons). Recent transfer press installations of approximately 3000 tons capacity allow for processing of an expanded range of higher strength steels.

Hot stamping requires a high-tonnage servo-driven press (approximately 1000 ton force capacity) with a 3 meter by 2 meter bolster, fed by either a roller-hearth furnace more than 30 m long or a multi-chamber furnace. Press hardened steels need to be heated to 900 °C for full austenitization in order to achieve a uniform consistent phase, and this contributes to energy requirements often exceeding 2 MW.

Integrating multiple functions into fewer parts leads to part consolidation. Accommodating large laser-welded parts such as combined front and rear door rings expands the need for even wider furnaces, higher-tonnage presses, and larger bolster dimensions.

Blanking of coils used in the PHS process occurs before the hardening step, so forces are low. Post-hardening trimming usually requires laser cutting, or possibly mechanical cutting if some processing was done to soften the areas of interest.

That contrasts with the blanking and trimming of high strength cold-forming grades. Except for the highest strength cold forming grades, both blanking and trimming tonnage requirements are sufficiently low that conventional mechanical cutting is used on the vast majority of parts. Cut edge quality and uniformity greatly impact the edge stretchability that may lead to unexpected fracture.

Responsibilities

Most cold stamped parts going into a given body-in-white are formed by a tier supplier. In contrast, some automakers create the vast majority of their hot stamped parts in-house, while others rely on their tier suppliers to provide hot stamped components. The number of qualified suppliers capable of producing hot stamped parts is markedly smaller than the number of cold stamping part suppliers.

Hot stamping is more complex than just adding heat to a cold stamping process. Suppliers of cold stamped parts are responsible for forming a dimensionally accurate part, assuming the steel supplier provides sheet metal with the required tensile properties achieved with a targeted microstructure.

Suppliers of hot stamped parts are also responsible for producing a dimensionally accurate part, but have additional responsibility for developing the microstructure and tensile properties of that part from a general steel chemistry typically described as 22MnB5.

Property Development

Independent of which company creates the hot formed part, appropriate quality assurance practices must be in place. With cold stamped parts, steel is produced to meet the minimum requirements for that grade, so routine property testing of the formed part is usually not performed. This is in contrast to hot stamped parts, where the local quench rate has a direct effect on tensile properties after forming. If any portion of the part is not quenched faster than the critical cooling rate, the targeted mechanical properties will not be met and part performance can be compromised. Many companies have a standard practice of testing multiple areas on samples pulled every run. It’s critical that these tested areas are representative of the entire part. For example, on the top of a hat-section profile where there is good contact between the punch and cavity, heat extraction is likely uniform and consistent. However, on the vertical sidewalls, getting sufficient contact between the sheet metal and the tooling is more challenging. As a result, the reduced heat extraction may limit the strengthening effect due to an insufficient quench rate.

Grade Options for Cold Stamped or Hot Formed Steel

There are two types of parts needed for vehicle safety cage applications: those with the highest strength that prevent intrusion, and those with some additional ductility that can help with energy absorption. Each of these types can be achieved via cold stamping or hot stamping.

When it comes to cold stamped parts, many grade options exist at 1000 MPa that also have decent ductility. The advent of the 3rd Generation Advanced High Strength Steels adds to the tally – the stress-strain curve of a 3ʳᵈ Gen QP980 steel is presented in Figure 1. Most of these top out at 1200 MPa, with some companies offering cold-formable Advanced High Strength Steels with 1400 or 1500 MPa tensile strength. The chemistry of AHSS grades is a function of the specific characteristics of each production mill, meaning that OEMs must exercise diligence when changing suppliers.

Figure 1: Stress-strain curve of industrially produced QP980.W-35

Martensitic grades from the steel mill have been in commercial production for many years, with minimum strength levels typically ranging from 900 MPa to 1470 MPa, depending on the grade. These products are typically destined for roll forming, except for possibly those at the lower strengths, due to limited ductility. Until recently, MS1470, a martensitic steel with 1470 MPa minimum tensile strength, was the highest strength cold formable option available. New offerings from global steelmakers now include MS1700, with a 1700 MPa minimum tensile strength, as well as MS 1470 with sufficient ductility to allow for cold stamping. Automakers have deployed these grades in cold stamped applications such as crossmembers and roof reinforcements, with some applications shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2: Cold-Stamped Martensitic Steel with 1500 MPa Tensile Strength used in the Nissan B-Segment Hatchback.K-57

Until these recent developments, hot stamping was the primary option to reach the highest strength levels in part shapes having even mild complexity. Under proper conditions, a chemistry of 22MnB5 could routinely reach a nominal or aim strength of 1500 MPa, which led to this grade being described as PHS1500, CR1500T-MB, or with similar nomenclature. Note that in this terminology, 1500 MPa nominal strength typically corresponds to a minimum strength of 1300 MPa.

The 22MnB5 chemistry is globally available, but the coating approaches discussed below may be company-specific.

Newer PHS options with a modified chemistry and subsequent processing differences can reach nominal strength levels of 2000 MPa. Other options are available with additional ductility at strength levels of 1000 MPa or 1200 MPa. A special class called Press Quenched Steels have even higher ductility with strength as low as 450 MPa.

The spectrum of grades available for cold-stamped and hot formed steel parts allows automakers to fine-tune the crash energy management features within a body structure, contributing to steel’s “infinite tune-ability” capability which gives automotive engineers design flexibility and freedoms not available from other structural materials.

Corrosion Protection

Uncoated versions of a grade must take a different chemistry approach than the hot dip galvanized (GI) or hot dipped galvannealed (HDGA) versions since the hot dip galvanizing process (Figure 3) acts as a heat treatment cycle that changes the properties of the base steel. Steelmakers adjust the base steel chemistry to account for this heat treatment to ensure the resultant properties fall within the grade requirements.

Figure 3: Schematic of a typical hot-dipped galvanizing line with galvanneal capability.

This strategy has limitations as it relates to grades with increasing amounts of martensite in the microstructure. Complex thermal cycles are needed to produce the highly engineered microstructures seen in advanced steels. Above a certain strength level, it is not possible to create a GI or HDGA version of that grade.

For example, when discussing fully martensitic grades from the steel mill, hot dip galvanizing is not an option. If a martensitic grade needs corrosion protection, then electrogalvanizing (Figure 4) is the common approach since an EG coating is applied at ambient temperature, which is low enough to avoid negatively impacting the properties. Automakers might choose to forgo a galvanized coating if the intended application is in a dry area that is not exposed to road salt.

Figure 4: Schematic of an electrogalvanizing line.

For press hardening steels, coatings serve multiple purposes. Without a coating, uncoated steels will oxidize in the austenitizing furnace and develop scale on the surface. During hot stamping, this scale layer limits efficient thermal transfer and may prevent the critical cooling rate from being reached. Furthermore, scale may flake off in the tooling, leading to tool surface damage. Finally, scale remaining after hot stamping is typically removed by shot blasting, an off-line operation that may induce additional issues.

Using a hot dip galvanized steel in a conventional direct press hardening process (blank -> heat -> form/quench) may contribute to liquid metal embrittlement (LME). Getting around this requires either changing the steel chemistry from the conventional 22MnB5 or using an indirect press hardening process that sees the bulk of the part shape formed at ambient temperatures followed by heating and quenching.

Those companies wishing to use the direct press hardening process can use a base steel having an aluminum-silicon (Al-Si) coating, providing that the heating cycle in the austenitizing furnace is such that there is sufficient time for alloying between the coating and the base steel. Welding practices using these coated steels need to account for the aluminum in the coating, but robust practices have been developed and are in widespread use.

Setting Correct Welding Parameters for Resistance Spot Welding

Specific welding parameters need to be developed for each combination of material type and thickness. In general, Press Hardening Steels require more demanding process conditions. One important factor is electrode force, which is typically higher than needed to weld cold formed steels of the same thickness. The actual recommended force depends on the strength level and the thickness of the steel. Of course, strength and thickness affects the welding machine/welding gun force capability requirement.

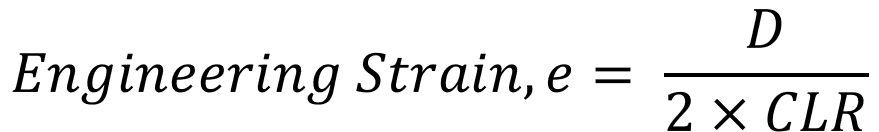

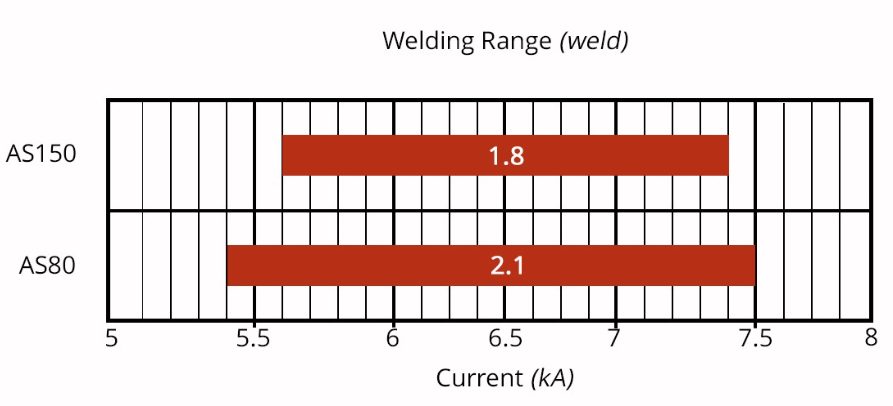

The welding current level, and more importantly, the current range are both important. The current range is one of the best indicators of welding process robustness, so it is sometimes described as the welding process window. Figure 5 indicates the relative range of current required for spot welding different steel types. A smaller process window may require more frequent weld quality evaluations, such as for adequate weld size, necessitating more frequent corrective actions to address the discovered quality concern.

Figure 5: Relative Current Range (process windows) for Different Steel Types

Effect of Coating Type on Weldability

When resistance spot welding coated steels, the coating must be removed from the weld area during and in the beginning of the weld cycle to allow a steel-to-steel weld to occur. The combination of welding current, weld time, and electrode force are responsible for this coating displacement.

For all coated steels, the ability of the coating to flow is a function of the coating type and properties such as electrical resistivity and melting point, as well as the coating thickness.

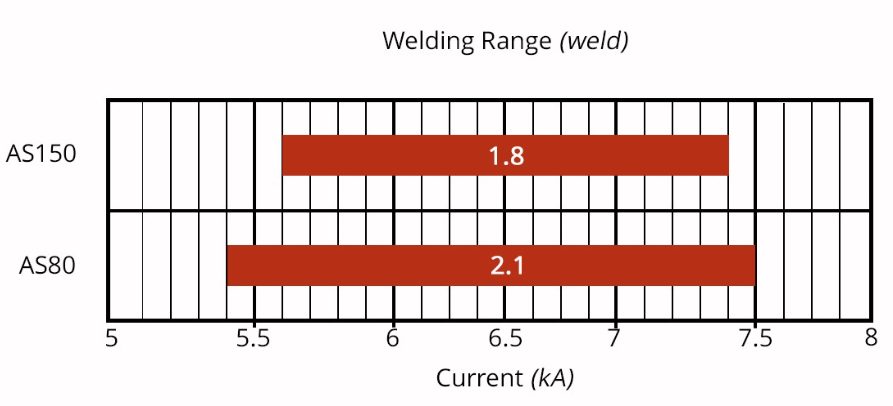

Cross sectioned spot welds made on press hardened steel with different coating weights of an Aluminum -Silicon coating is presented in Figure 6. Note the displaced coating at the periphery of weld. Figure 7 shows the difference in current range required to produce acceptable welds associated with these different coating weights. The thicker coating shows a smaller current range. In addition, the press-hardened Al-Si coating has a much higher melting point than the zinc coatings typically found on cold stamped steels, making it more difficult to displace from the weld area.

Figure 6: Aluminum -Silicon coated press hardened steels.O-16

Figure 7: Influence of Aluminum-Silicon coating weight on welding range.O-16

Liquid Metal Embrittlement and Resistance Spot Welding

Cold-formable, coated, Advanced High Strength Steels are widely used in automotive applications. One welding issue these materials encounter is increased hardness in the weld area, that may result in brittle fracture of the weld. Another issue is their sensitivity to Liquid Metal Embrittlement (LME) cracking.

Both issues are discussed in detail in the Joining section of the WorldAutoSteel AHSS Guidelines website and the WorldAutoSteel Phase 2 Report on LME.

Resistance Spot Welding Using Current Pulsation

The most effective solution for these issues is using current pulsation during the welding cycle, schematically described in Figure 8.

Figure 8: Nugget growth differences in Single Pulse vs. Multi-Pulse Welding

Pulsation of the current allows much better control of the heat generation and weld nugget development. Pulsation variables include the number of pulses (typically 2 to 4), current, time for each pulse, and the cool time between the pulses.

Pulsation during Resistance Spot Welding is beneficial for press hardening steels, coated cold stamped steels of all grades, and multi-material stack-ups. Information about multi-sheet, multi-material stack-ups can be – as described in our articles on 3T/4T and 5T Stack-Ups

For more information about PHS grades and processing, see our Press Hardened Steel Primer.

Thanks are given to Eren Billur, Ph.D., Billur MetalForm for his contributions to the Equipment section, as well as many of the webpages relating to Press Hardening Steels at www.AHSSinsights.org.

Blog, homepage-featured-top, main-blog

Equipment, Responsibilities, and Property Development Considerations When Deciding How A Part Gets Formed

Automakers contemplating whether a part is cold stamped or hot formed must consider numerous ramifications impacting multiple departments. Over a series of blogs, we’ll cover some of the considerations that must enter the discussion.

The discussions relative to cold stamping are applicable to any forming operation occurring at room temperature such as roll forming, hydroforming, or conventional stamping. Similarly, hot stamping refers to any set of operations using Press Hardening Steels (or Press Quenched Steels), including those that are roll formed or fluid-formed.

Equipment

There is a well-established infrastructure for cold stamping. New grades benefit from servo presses, especially for those grades where press force and press energy must be considered. Larger press beds may be necessary to accommodate larger parts. As long as these factors are considered, the existing infrastructure is likely sufficient.

Progressive-die presses have tonnage ratings commonly in the range of 630 to 1250 tons at relatively high stroke rates. Transfer presses, typically ranging from 800 to 2500 tons, operate at relatively lower stroke rates. Power requirements can vary between 75 kW (630 tons) to 350 kW (2500 tons). Recent transfer press installations of approximately 3000 tons capacity allow for processing of an expanded range of higher strength steels.

Hot stamping requires a high-tonnage servo-driven press (approximately 1000 ton force capacity) with a 3 meter by 2 meter bolster, fed by either a roller-hearth furnace more than 30 m long or a multi-chamber furnace. Press hardened steels need to be heated to 900 °C for full austenitization in order to achieve a uniform consistent phase, and this contributes to energy requirements often exceeding 2 MW.

Integrating multiple functions into fewer parts leads to part consolidation. Accommodating large laser-welded parts such as combined front and rear door rings expands the need for even wider furnaces, higher-tonnage presses, and larger bolster dimensions.

Blanking of coils used in the PHS process occurs before the hardening step, so forces are low. Post-hardening trimming usually requires laser cutting, or possibly mechanical cutting if some processing was done to soften the areas of interest.

That contrasts with the blanking and trimming of high strength cold-forming grades. Except for the highest strength cold forming grades, both blanking and trimming tonnage requirements are sufficiently low that conventional mechanical cutting is used on the vast majority of parts. Cut edge quality and uniformity greatly impact the edge stretchability that may lead to unexpected fracture.

Responsibilities

Most cold stamped parts going into a given body-in-white are formed by a tier supplier. In contrast, some automakers create the vast majority of their hot stamped parts in-house, while others rely on their tier suppliers to provide hot stamped components. The number of qualified suppliers capable of producing hot stamped parts is markedly smaller than the number of cold stamping part suppliers.

Hot stamping is more complex than just adding heat to a cold stamping process. Suppliers of cold stamped parts are responsible for forming a dimensionally accurate part, assuming the steel supplier provides sheet metal with the required tensile properties achieved with a targeted microstructure.

Suppliers of hot stamped parts are also responsible for producing a dimensionally accurate part, but have additional responsibility for developing the microstructure and tensile properties of that part from a general steel chemistry typically described as 22MnB5.

Property Development

Independent of which company creates the hot formed part, appropriate quality assurance practices must be in place. With cold stamped parts, steel is produced to meet the minimum requirements for that grade, so routine property testing of the formed part is usually not performed. This is in contrast to hot stamped parts, where the local quench rate has a direct effect on tensile properties after forming. If any portion of the part is not quenched faster than the critical cooling rate, the targeted mechanical properties will not be met and part performance can be compromised. Many companies have a standard practice of testing multiple areas on samples pulled every run. It’s critical that these tested areas are representative of the entire part. For example, on the top of a hat-section profile where there is good contact between the punch and cavity, heat extraction is likely uniform and consistent. However, on the vertical sidewalls, getting sufficient contact between the sheet metal and the tooling is more challenging. As a result, the reduced heat extraction may limit the strengthening effect due to an insufficient quench rate.

For more information, see our Press Hardened Steel Primer to learn more about PHS grades and processing!

Thanks are given to Eren Billur, Ph.D., Billur MetalForm for his contributions to the Equipment section, as well as many of the webpages relating to Press Hardening Steels at www.AHSSinsights.org.

Danny Schaeffler is the Metallurgy and Forming Technical Editor of the AHSS Applications Guidelines available from WorldAutoSteel. He is founder and President of Engineering Quality Solutions (EQS). Danny wrote the monthly “Science of Forming” and “Metal Matters” column for Metalforming Magazine, and provides seminars on sheet metal formability for Auto/Steel Partnership and the Precision Metalforming Association. He has written for Stamping Journal and The Fabricator, and has lectured at FabTech. Danny is passionate about training new and experienced employees at manufacturing companies about how sheet metal properties impact their forming success.

Blog, homepage-featured-top, main-blog, Roll Forming

Roll Forming

Case Study: How Steel Properties Influence the Roll Forming Process

Coil Shape Imperfections Influencing Roll Forming

Roll Stamping

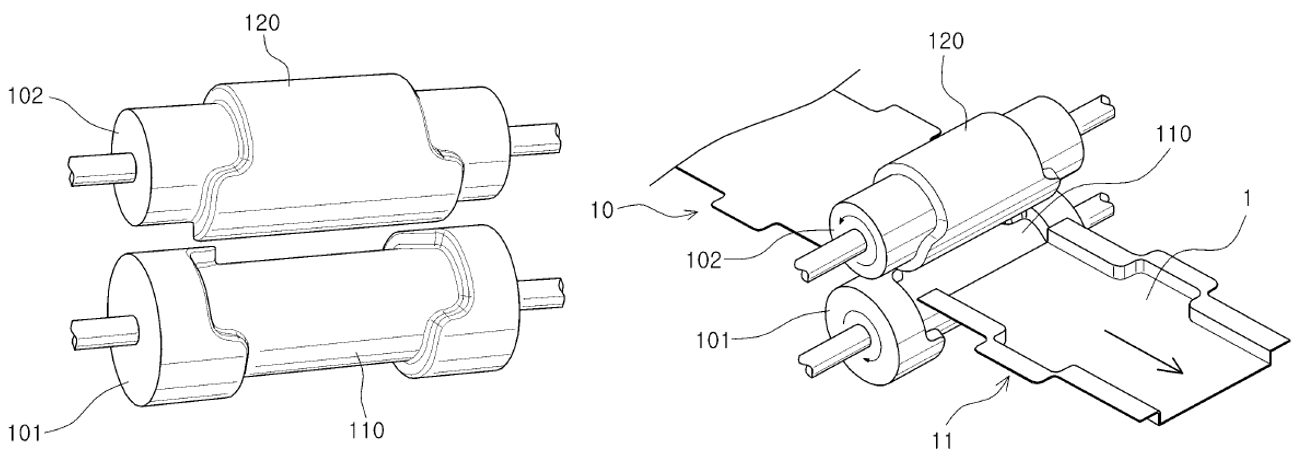

Roll Forming takes a flat sheet or strip and feeds it longitudinally through a mill containing several successive paired roller dies, each of which incrementally bends the strip into the desired final shape. The incremental approach can minimize strain localization and compensate for springback. Therefore, roll forming is well suited for generating many complex shapes from Advanced High-Strength Steels, especially from those grades with low total elongation, such as martensitic steel. The following video, kindly provided by Shape Corp.S-104, highlights the process that can produce either open or closed (tubular) sections.

The number of pairs of rolls depends on the sheet metal grade, finished part complexity, and the design of the roll-forming mill. A roll-forming mill used for bumpers may have as many as 30 pairs of roller dies mounted on individually driven horizontal shafts.A-32

Roll forming is one of the few sheet metal forming processes requiring only one primary mode of deformation. Unlike most forming operations, which have various combinations of forming modes, the roll-forming process is nothing more than a carefully engineered series of bends. In roll forming, metal thickness does not change appreciably except for a slight thinning at the bend radii.

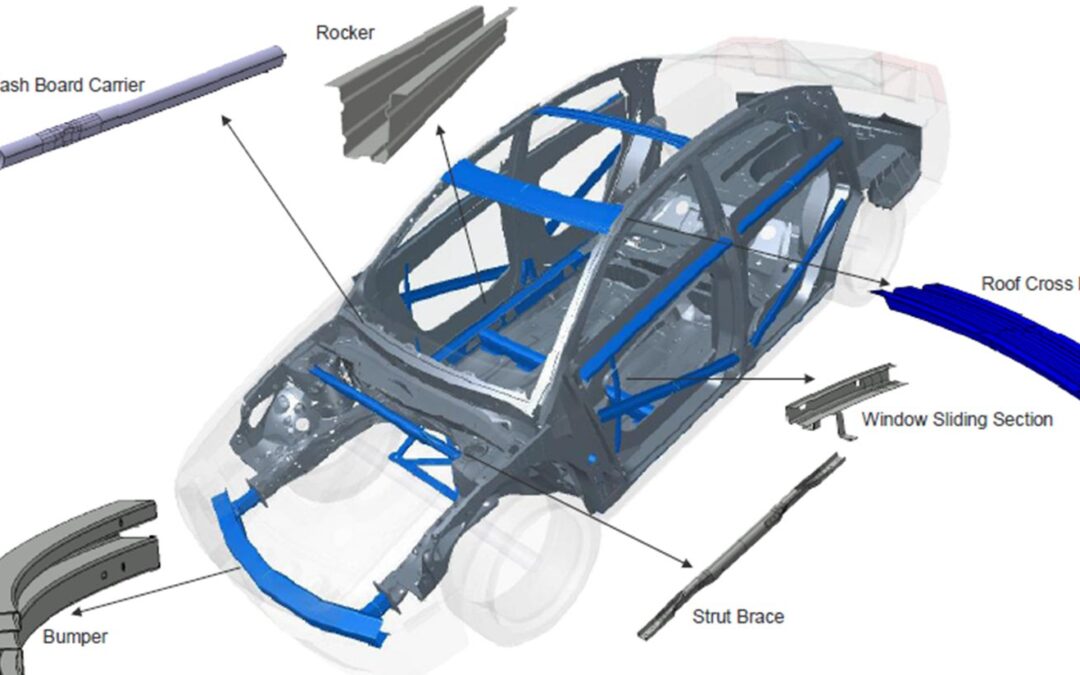

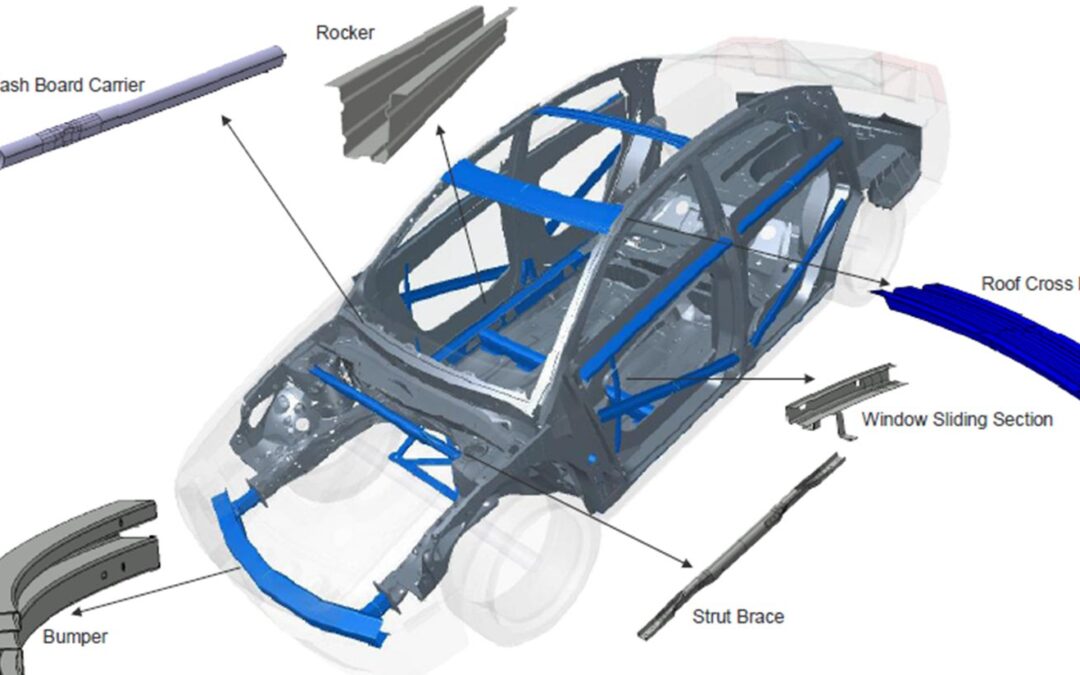

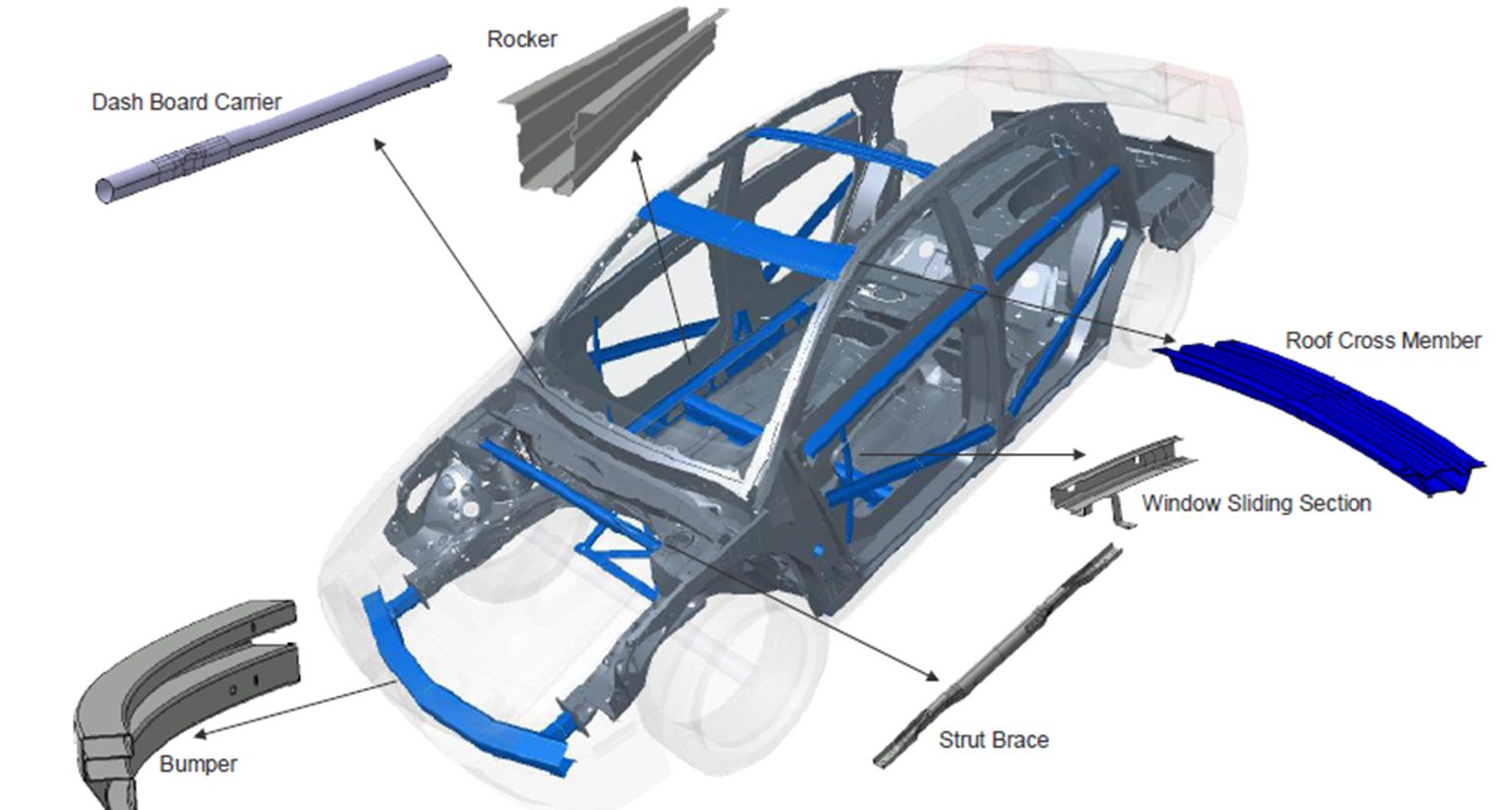

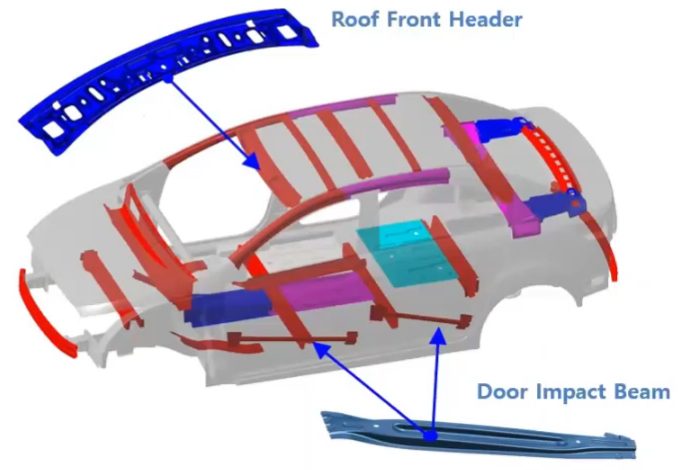

Roll forming is appropriate for applications requiring high-volume production of long lengths of complex sections held to tight dimensional tolerances. The continuous process involves coil feeding, roll forming, and cutting to length. Notching, slotting, punching, embossing, and curving combine with contour roll forming to produce finished parts off the exit end of the roll-forming mill. In fact, companies directly roll-form automotive door beam impact bars to the appropriate sweep and only need to weld on mounting brackets prior to shipment to the vehicle assembly line.A-32 Figure 1 shows an example of automotive applications that are ideal for the roll-forming process.

Figure 1: Body components that are ideally suited for roll-forming.

Roll forming can produce AHSS parts with:

- Steels of all levels of mechanical properties and different microstructures.

- Small radii depending on the thickness and mechanical properties of the steel.

- Reduced number of forming stations compared with lower strength steel.

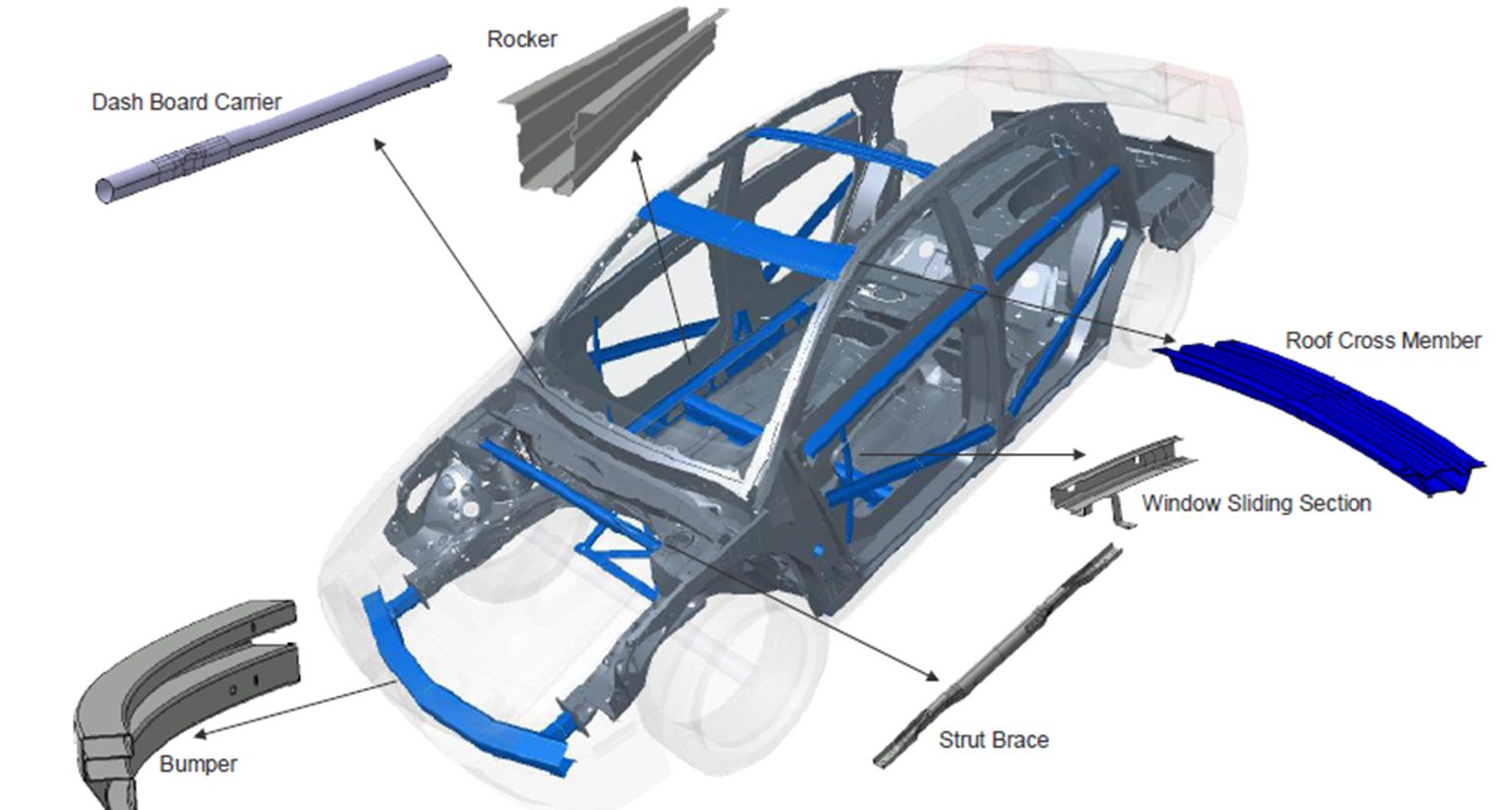

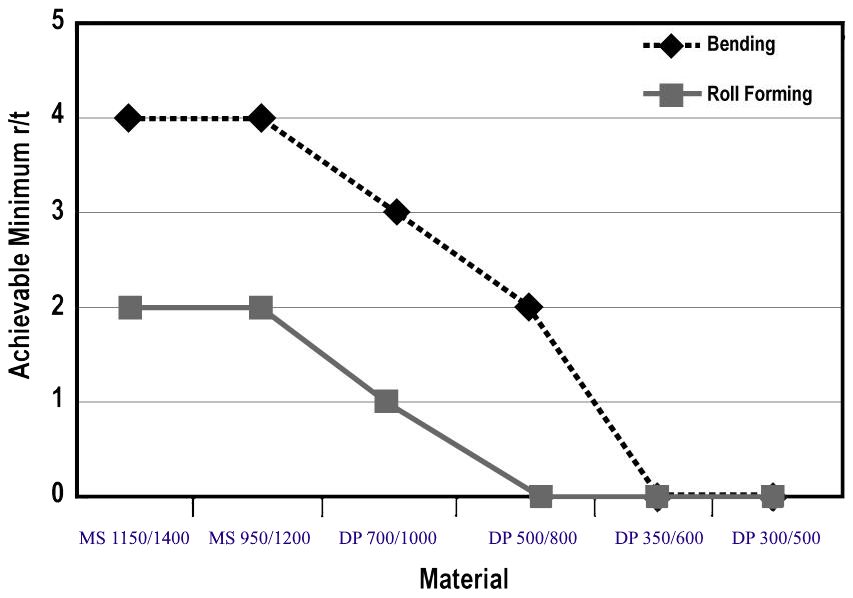

However, the high sheet-steel strength means that forces on the rollers and frames in the roll-forming mill are higher. A rule of thumb says that the force is proportional to the strength and thickness squared. Therefore, structural strength ratings of the roll forming equipment must be checked to avoid bending of the shafts. The value of minimum internal radius of a roll formed component depends primarily on the thickness and the tensile strength of the steel (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Achievable minimum r/t values for bending and roll forming for different strength and types of steel.S-5

As seen in Figure 2, roll forming allows smaller radii than a bending process. Figure 3 compares CR1150/1400-MS formed with air-bending and roll forming. Bending requires a minimum 3T radius, but roll forming can produce 1T bends.S-30

Figure 3: CR1150/1400-MS (2 mm thick) has a minimum bend radius of 3T, but can be roll formed to a 1T radius.S-30

The main parameters having an influence on the springback are the radius of the component, the sheet thickness, and the strength of the steel. As expected, angular change increases for increased tensile strength and bend radius (Figure 4).

Figure 4: Angular change increases with increasing tensile strength and bend radii.A-4

Figure 5 shows a profile made with the same tool setup for three steels at the same thickness having tensile strength ranging from 1000 MPa to 1400 MPa. Even with the large difference in strength, the springback is almost the same.

Figure 5: Roll formed profile made with the same tool setup for three different steels. Bottom to Top: CR700/1000-DP, CR950/1200-MS, CR1150/1400-MS.S-5

Citation A-33 provides guidelines for roll forming High-Strength Steels:

- Select the appropriate number of roll stands for the material being formed. Remember the higher the steel strength, the greater the number of stands required on the roll former.

- Use the minimum allowable bend radius for the material in order to minimize springback.

- Position holes away from the bend radius to help achieve desired tolerances.

- Establish mechanical and dimensional tolerances for successful part production.

- Use appropriate lubrication.

- Use a suitable maintenance schedule for the roll forming line.

- Anticipate end flare (a form of springback). End flare is caused by stresses that build up during the roll forming process.

- Recognize that as a part is being swept (or reformed after roll forming), the compression of metal can cause sidewall buckling, which leads to fit-up problems.

- Do not roll form with worn tooling, as the use of worn tools increases the severity of buckling.

- Do not expect steels of similar yield strength from different steel sources to behave similarly.

- Do not over-specify tolerances.

Guidelines specifically for the highest strength steelsA-33:

- Depending on the grade, the minimum bend radius should be three to four times the thickness of the steel to avoid fracture.

- Springback magnitude can range from ten degrees for 120X steel (120 ksi or 830 MPa minimum yield strength, 860 MPa minimum tensile strength) to 30 degrees for M220HT (CR1200/1500-MS) steel, as compared to one to three degrees for mild steel. Springback should be accounted for when designing the roll forming process.

- Due to the higher springback, it is difficult to achieve reasonable tolerances on sections with large radii (radii greater than 20 times the thickness of the steel).

- Rolls should be designed with a constant radius and an evenly distributed overbend from pass to pass.

- About 50 percent more passes (compared to mild steel) are required when roll forming ultra high-strength steel. The number of passes required is affected by the number of profile bends, mechanical properties of the steel, section depth-to-steel thickness ratio, tolerance requirements, pre-punched holes and notches.

- Due to the higher number of passes and higher material strength, the horsepower requirement for forming is increased.

- Due to the higher material strength, the forming pressure is also higher. Larger shaft diameters should be considered. Thin, slender rolls should be avoided.

- During roll forming, avoid undue permanent elongation of portions of the cross section that will be compressed during the sweeping process.

Roll forming is applicable to shapes other than long, narrow parts. For example, an automaker roll forms their pickup truck beds allowing them to minimize thinning and improve durability (Figure 6). Reduced press forces are another factor that can influence whether a company roll forms rather than stamps truck beds.

In addition, increasing the number of passes has been shown to be an effective technique to lower residual stresses and therefore improve dimensional accuracy. Multiple bending sequences, especially in the transverse direction also improve dimensional accuracy, providing the steel has sufficient inherent formability to accommodate the additional bends.X-4

Figure 6: Roll Forming can replace stamping in certain applications.G-9

Traditional two-dimensional roll forming uses sequential roll stands to incrementally change flat sheets into the targeted shape having a consistent profile down the length. Advanced dynamic roll forming incorporates computer-controlled roll stands with multiple degrees of freedom that allow the finished profile to vary along its length, creating a three-dimensional profile. The same set of tools create different profiles by changing the position and movements of individual roll stands. In-line 3D profiling expands the number of applications where roll forming is a viable parts production option.

One such example are the 3D roll formed tubes made from 1700 MPa martensitic steel for A-pillar / roof rail applications in the 2020 Ford Explorer and 2020 Ford Escape (Figure 7). Using this approach instead of hydroforming created smaller profiles resulting in improved driver visibility, more interior space, and better packaging of airbags. The strength-to-weight ratio improved by more than 50 percent, which led to an overall mass reduction of 2.8 to 4.5 kg per vehicle.S-104

Figure 7: 3D Roll Formed Profiles in 2020 Ford Vehicles using 1700 MPa martensitic steel.S-104

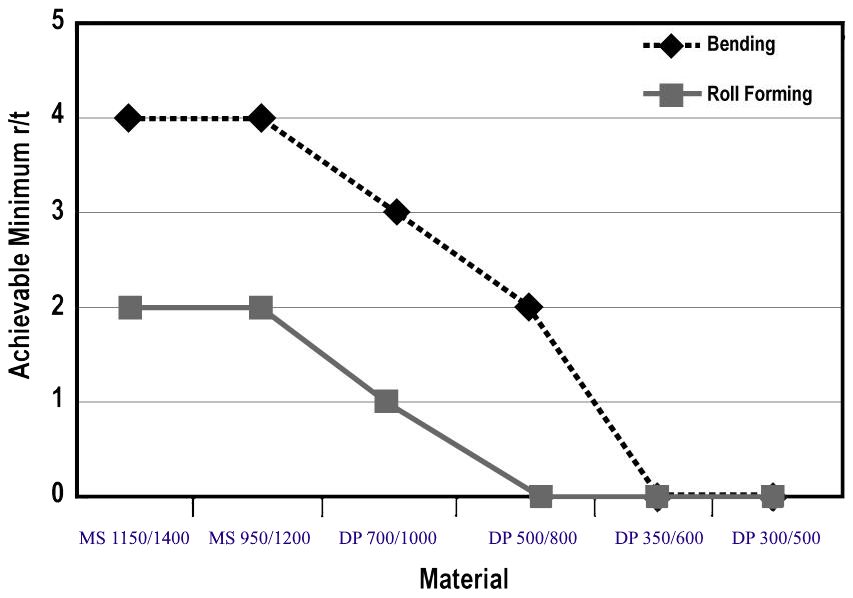

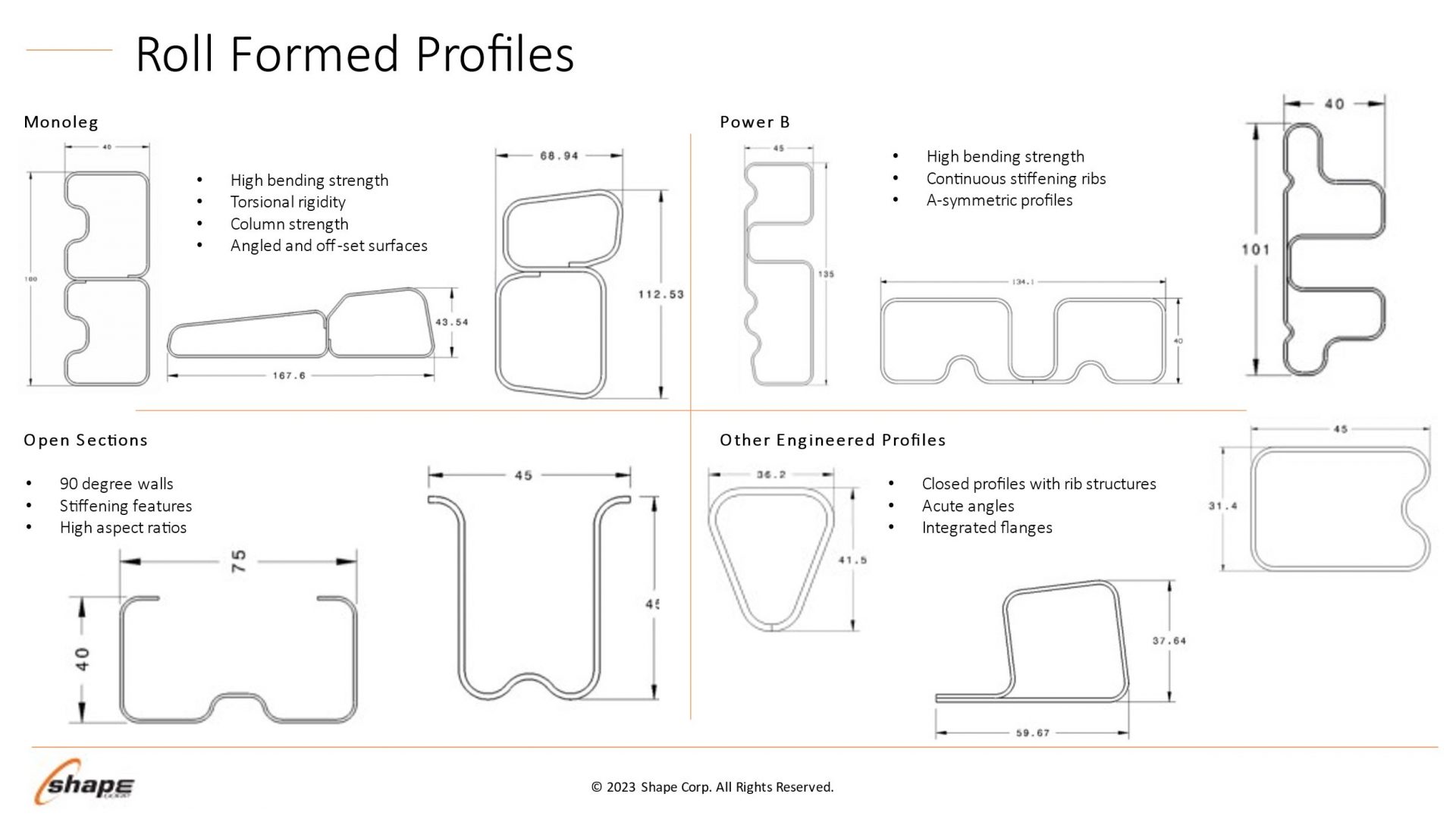

Roll forming is no longer limited to producing simple circular, oval, or rectangular profiles. Advanced cross sections such

as those shown in Figure 8 provided by Shape Corporation highlight some profile designs aiding in body structure

stiffness and packaging space reductions.

Figure 8: Roll forming profile design possibilities. Courtesy of Shape Corporation.

In summary, roll forming can produce AHSS parts with steels of all levels of mechanical properties and different microstructures with a reduced R/T ratio versus conventional bending. All deformation occurs at a radius, so there is no sidewall curl risk and overbending works to control angular springback.

Many thanks to Brian Oxley, Product Manager, Shape Corporation, and Dr. Daniel Schaeffler, President, Engineering Quality Solutions, Inc., for providing this case study.

Optimizing the use of roll forming requires understanding how the sheet metal behaves through the process.

Making a bend in a roll formed part occurs only when forming forces exceed the metal’s yield strength, causing plastic

deformation to occur. Higher strength sheet metals increase forming force requirements, leading to the need to have

larger shaft diameters in the roll forming mill. Each pass must have greater overbend to compensate for the increasing

springback associated with the higher strength.

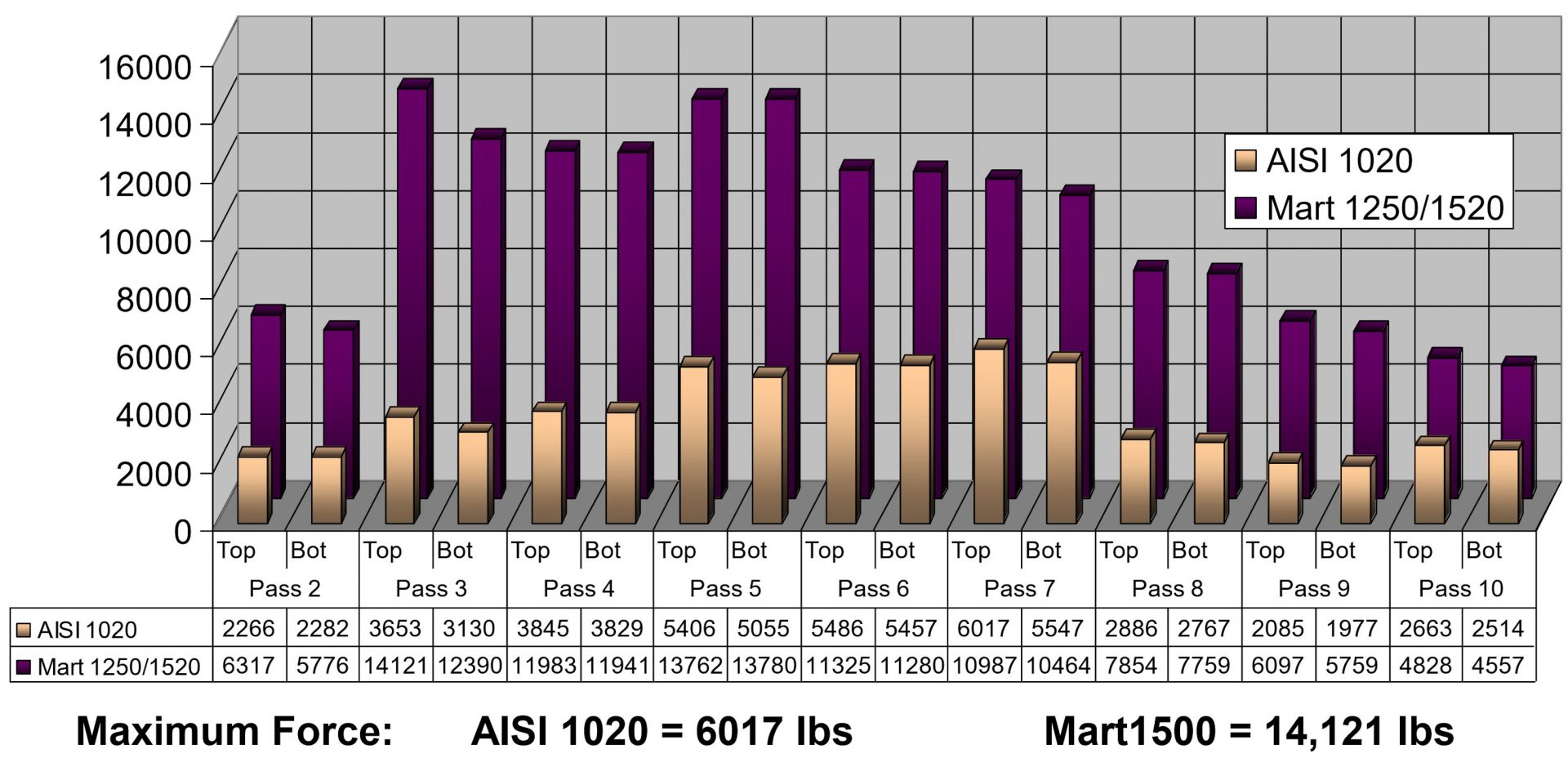

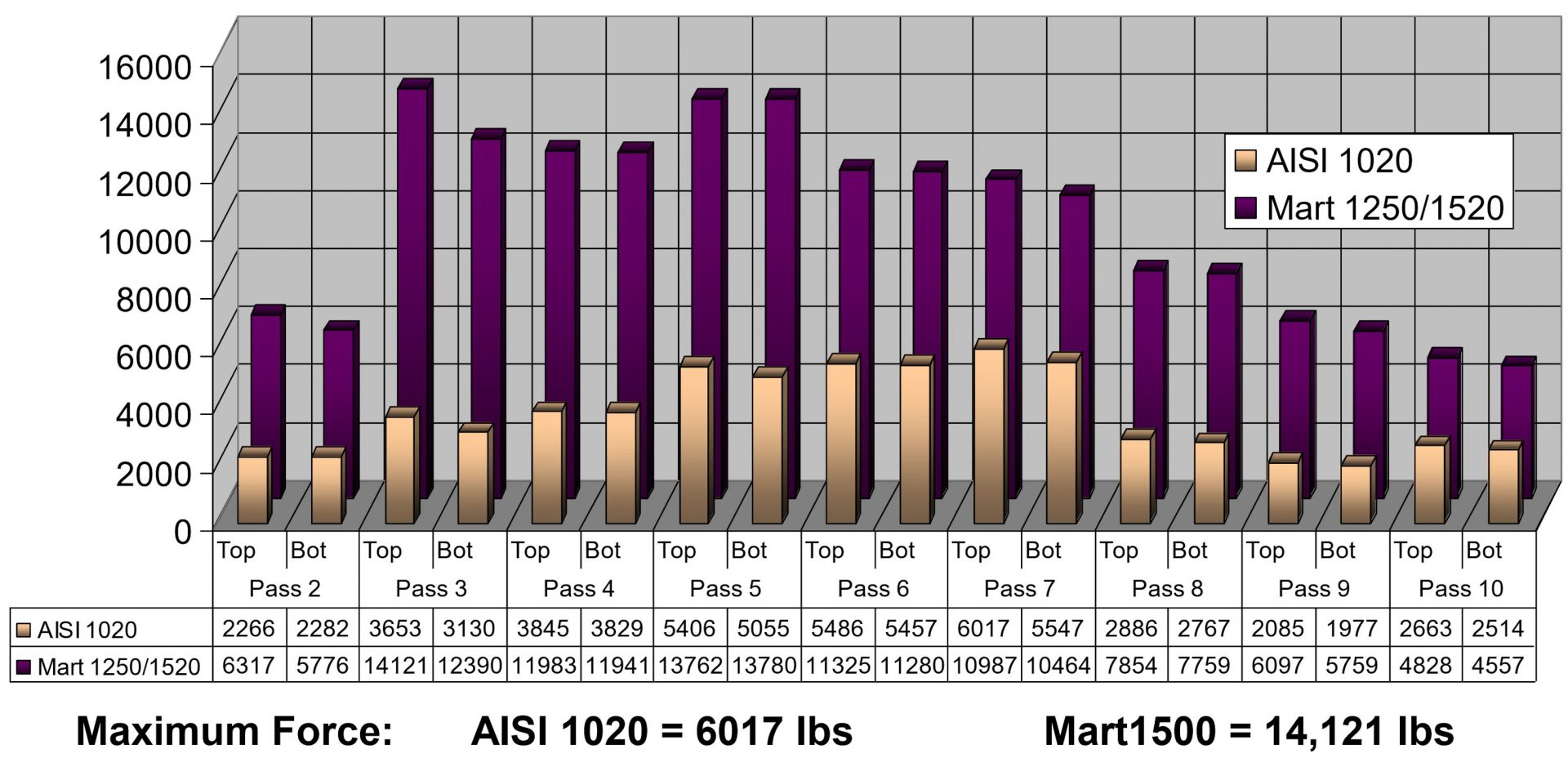

Figure 9 provides a comparison of the loads on each pass of a 10-station roll forming line when forming either AISI 1020

steel (yield strength of 350 MPa, tensile strength of 450 MPa, elongation to fracture of 15%) or CR1220Y1500T-MS, a

martensitic steel with 1220 MPa minimum yield strength and 1500 MPa minimum tensile strength.

Figure 9: Loads on each pass of a roll forming line when forming either AISI 1020 steel (450 MPa tensile

strength) or a martensitic steel with 1500 MPa minimum tensile strength. Courtesy of Roll-Kraft.

Although a high-strength material requires greater forming loads, grades with higher yield strength can resist stretching

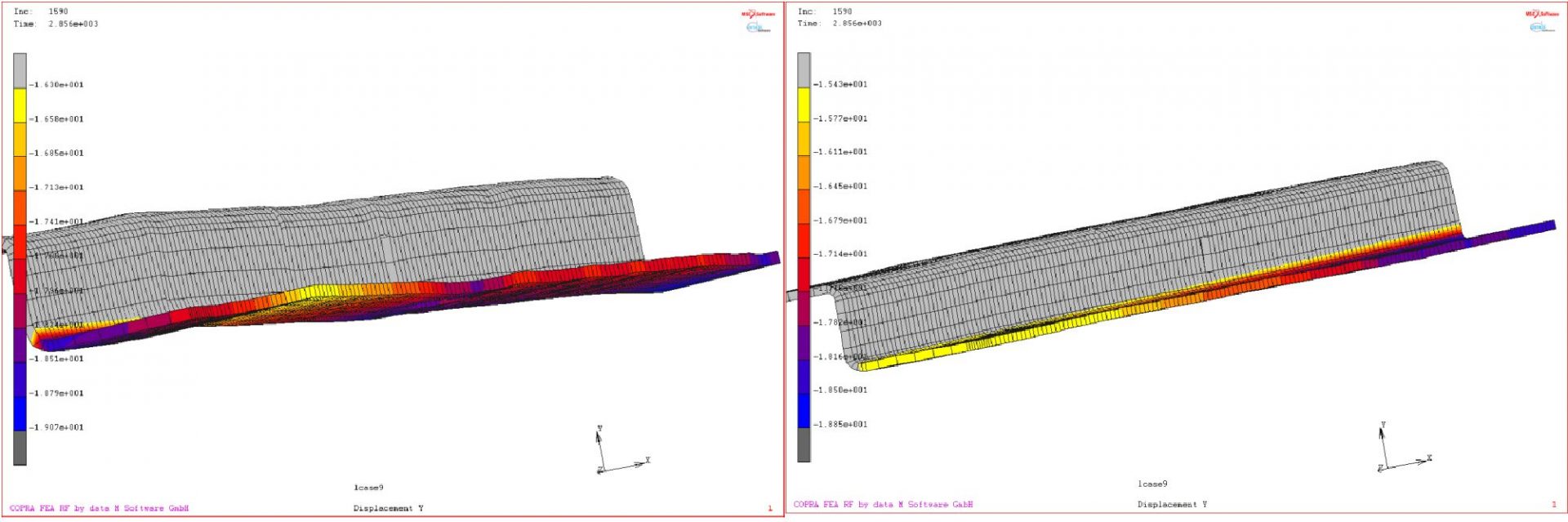

of the strip edge and prevent longitudinal deformations such as twisting or bow. Flange edge flatness after forming

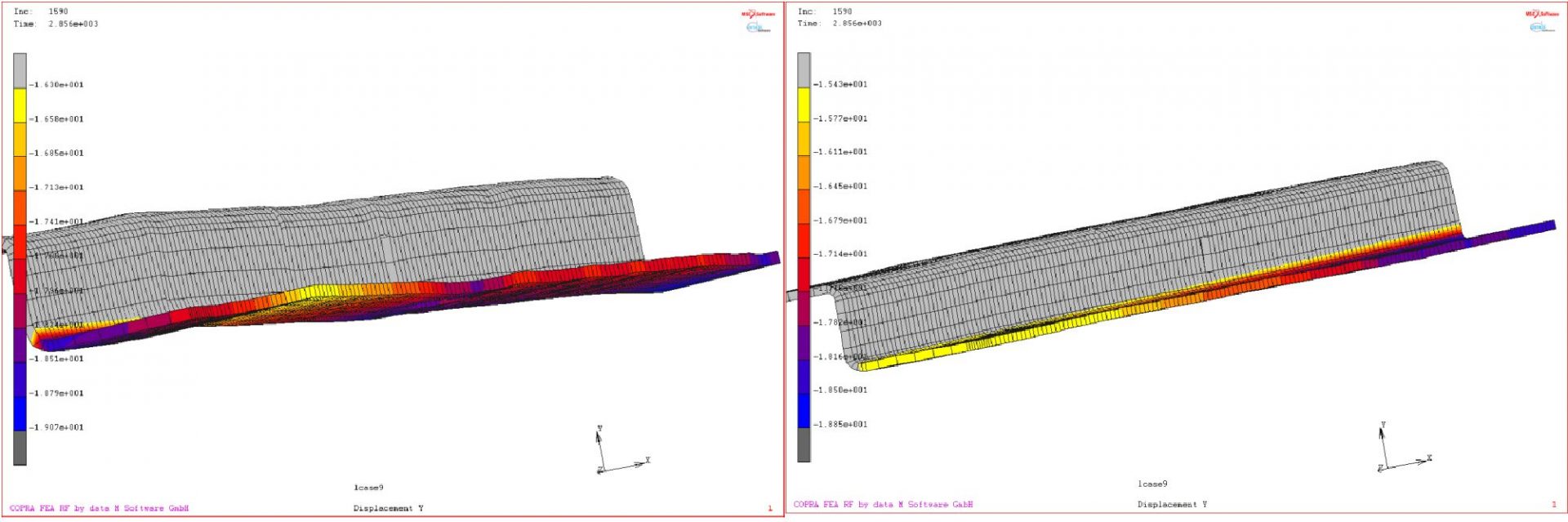

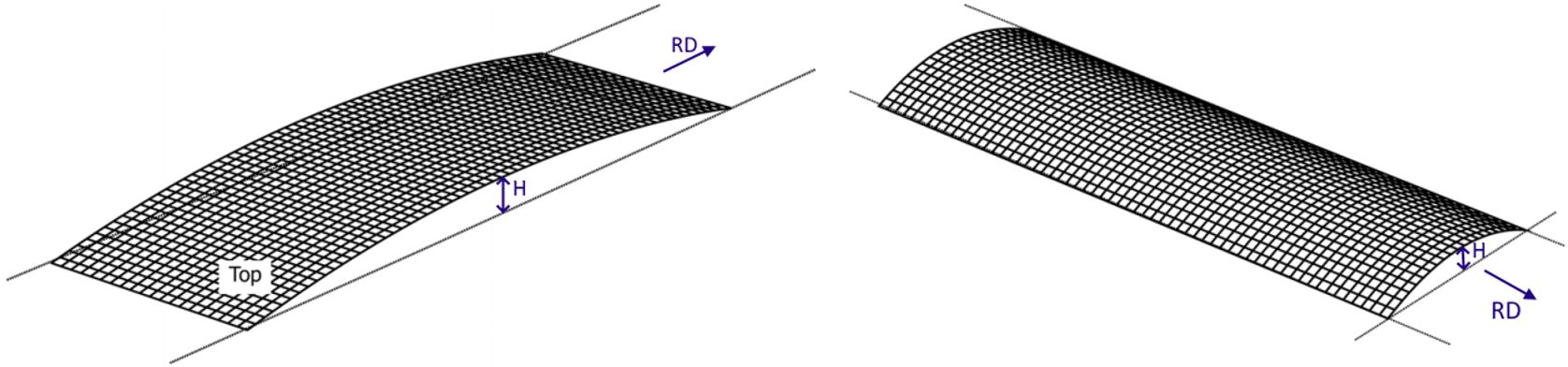

either AISI 1020 or CR1220Y1500T-MS is presented in Figure 10.

Figure 10: Simulation results showing flange edge flatness of a) AISI 1020 and b) CR1220Y1500T-MS.

Assumptions for the simulation: AISI 1020 yield strength = 350 MPa; CR1220Y1500T yield strength = 1220 MPa.

Higher yield strength leads to better flatness.

Force requirements for piercing operations are a function of the sheet tensile strength. High strains in the part design

exceeding uniform elongation resulting from loads in excess of the tensile strength produces local necking, representing

a structural weak point. However, assuming the design does not produce these high strains, the tensile strength has only

an indirect influence on the roll forming characteristics.

Yield strength and flow stress are the most critical steel characteristics for roll forming dimensional control. Receiving

metal with limited yield strength variability results in consistent part dimensions and stable locations for pre-pierced

features.

Flow stress represents the strength after some amount of deformation, and is therefore directly related to the degree of

work hardening: starting at the same yield strength, a higher work hardening steel will have a higher flow stress at the

same deformation.

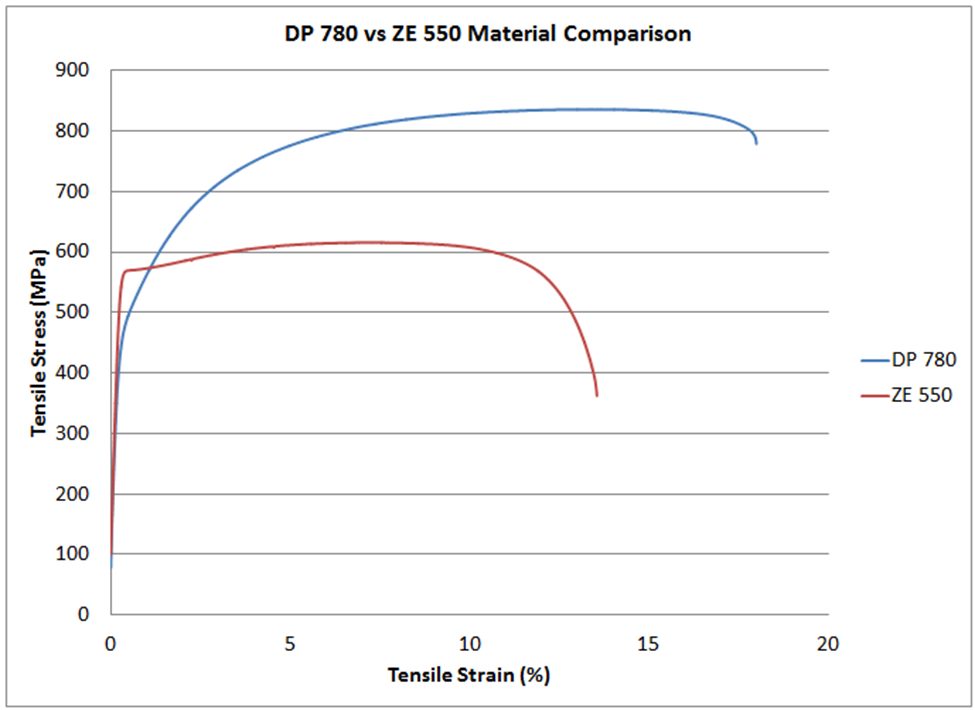

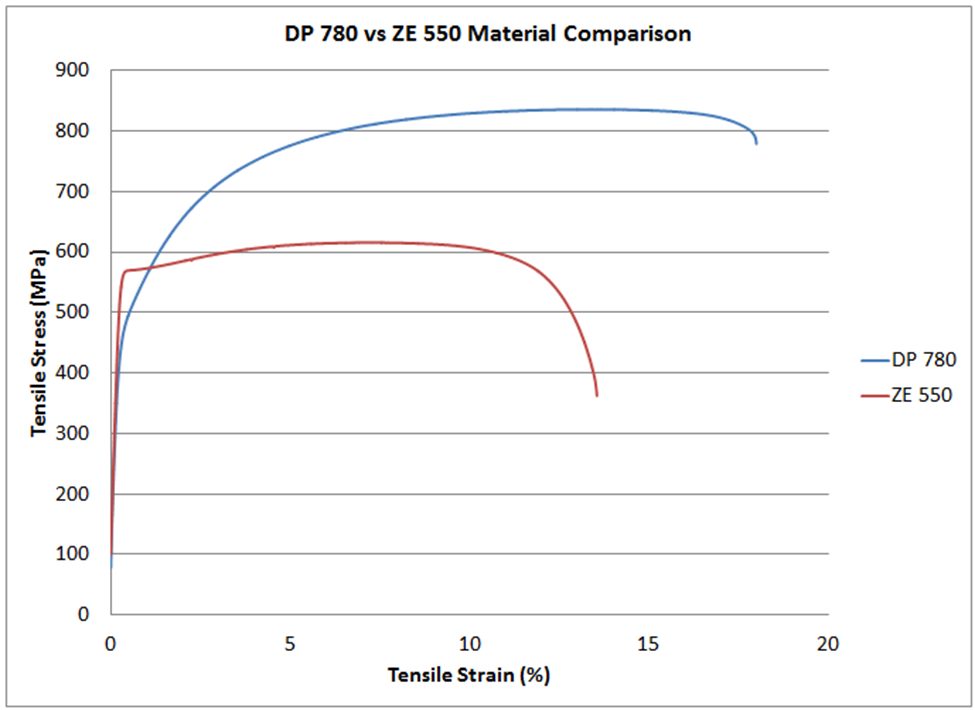

Two grades are shown in Figure 11: ZE 550 and CR420Y780T-DP. ZE 550, represented by the red curve, is a recovery

annealed grade made by Bilstein having a yield strength range of 550 to 625 MPa and a minimum tensile strength of 600

MPa, while CR420Y780T-DP, represented by the blue curve, is a conventional dual phase steel with a minimum yield

strength of 420 MPa and a minimum tensile strength of 780 MPa. For the samples tested, ZE 550 has a yield strength of

approximately 565 MPa, where that for CR420Y780T-DP is much lower at about 485 MPa. Due to the higher work

hardening (n-value) of the DP steel, its flow stress at 5% strain is 775 MPa, while the flow stress for the HSLA grade at 5%

strain is 620 MPa.

In conventional stamping operations, this work hardening is beneficial to delay the onset of necking. However, use of

dual-phase steels and other grades with high n-value can lead to dimensional issues in roll-formed parts. Flow stress in a

given area is a function of the local strain. Each roll station induces additional strain on the overall part, and strains vary

within the part and along the edge. This strength variation is responsible for differing springback and edge wave across

a roll-formed part.

Unlike conventional stamping, grades with a high yield/tensile ratio where the yield strength is close to the tensile

strength are better suited to produce straight parts via roll forming.

Figure 11: Stress-strain curves for CR420Y780T-DP (blue) and ZE 550 (red). See text for description of the grades.

Total elongation to fracture is the strain at which the steel breaks during tensile testing, and is a value commonly

reported on certified metal property documents (cert sheets). As observed on the colloquially called “banana diagram”,

elongation generally decreases as the strength of the steel increases.

For lower strength steels, total elongation is a good indicator for a metal’s bendability. Bend severity is described by the

r/t ratio, or the ratio of the inner bend radius to the sheet thickness. The metal’s ability to withstand a given bend can be

approximated by the tensile test elongation, since during a bend, the outermost fibers elongate like a tensile test.

In higher strength steels where the phase balance between martensite, bainite, austenite, and ferrite play a much larger

role in developing the strength and ductility than in other steels, bendability is usually limited by microstructural

uniformity. Dual phase steels, for example, have excellent uniform elongation and resistance to necking coming from

the hardness difference between ferrite and martensite. However, this large hardness difference is also responsible for

relatively poor edge stretchability and bendability. In roll forming applications, those grades with a uniform

microstructure will typically have superior performance. As an example, refer to Figure 11. The dual phase steel shown

in blue can be bent to a 2T radius before cracking, but the recovery annealed ZE 550 grade with noticeably higher yield

strength and lower elongation can be bent to a ½T radius.

Remember that each roll forming station only incrementally deforms the sheet, with subsequent stations working on a

different region. Roll formed parts do not need to use grades associated with high total elongation, especially since

these typically have a bigger gap between yield and tensile strength.

Along with the mechanical properties of steel, physical shape attributes of the sheet or coil can influence the roll

forming process. These include center buckle, coil set, cross bow, and camber. Receiving coils with these imperfections

may result in substandard roll formed parts.

Flatness is paramount when it comes to getting good shape on roll formed parts. Individual OEMs or processors may

have company-specific procedures and requirements, while organizations like ASTM offer similar information in the

public domain. ASTM A1030/A1030M is one standard covering the practices for measuring flatness, and specification

ASTM A568/A568M shows methods for characterizing longitudinal waves, buckles, and camber.

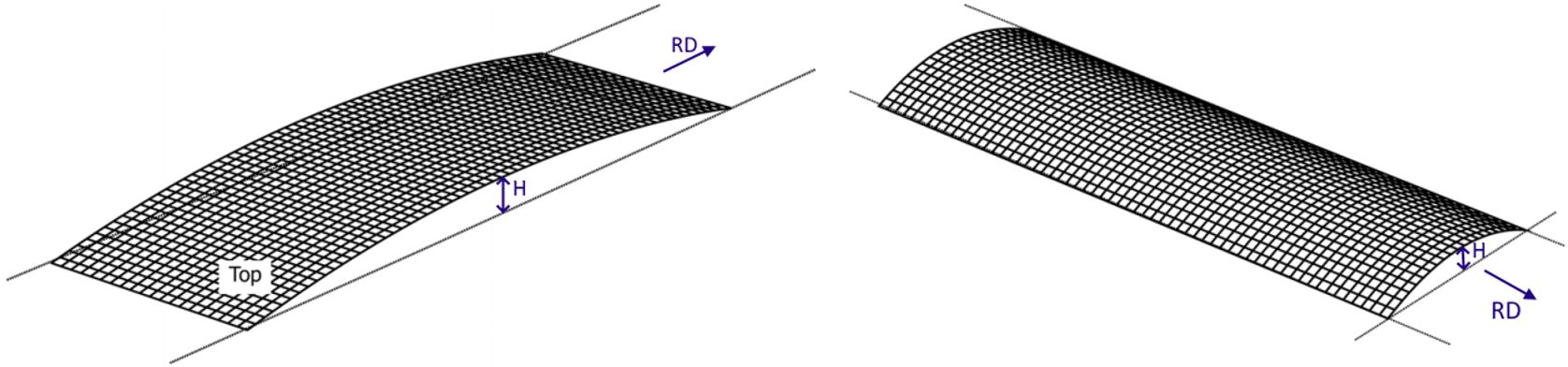

Center buckle (Figure 12), also known as full center, is the term to describe pockets or waves in the center or quarter

line of the strip. The height of pocket varies from 1/6” to 3/4”. Center buckle occurs when the central width portion of

the master coil is longer than the edges. This over-rolling of the center portion might occur when there is excessive

crown in the work roll, build-up from the hot strip mill, a mismatched set of work rolls, improper use of the benders, or

improper rolling procedures. A related issue is edge buckle presenting as wavy edges, originating when the coil edges

are longer than the central width position.

Figure 12: Coil shape imperfection: Center Buckle

Coil set (Figure 13a), also known as longitudinal bow, occurs when the top surface of the strip is stretched more than the

bottom surface, causing a bow condition parallel with the rolling direction. Here, the strip exhibits a tendency to curl

rather than laying flat. To some extent, coil set is normal, and easy to address with a leveler. Severe coil set may be

induced by an imbalance in the stresses induced during rolling by the thickness reduction work rolls. Potential causes include different diameters or surface speeds of the two work rolls, or different frictional conditions along the two arcs

of contact.

Crossbow (Figure 13b) is a bow condition perpendicular to the rolling direction, and arcs downward from the high point

in the center position across the width of the sheet. Crossbow may occur if improper coil set correction practices are

employed.

Figure 13: Coil shape imperfections: A) Coil set and B) Crossbow A-30

Camber (Figure 14) is the deviation of a side edge from a straight edge, and results when one edge of the steel is

elongated more than the other during the rolling process due to a difference in roll diameter or speed. The maximum

allowable camber under certain conditions is contained within specification ASTM A568/A568M, among others.

Figure 14: Coil shape imperfection: Camber

Coil shape imperfections produce residual stresses in the starting material. These residual stresses combined with the

stresses from forming lead to longitudinal deviations from targeted dimensions after roll forming. Some of the resultant

shapes of roll formed components made from coils having these issues are shown in Figure 15. Leveling the coil prior to

roll forming may address some of these shape concerns, and has the benefit of increasing the yield strength, making a

more uniform product.

Figure 15: Shape deviations in roll formed components initiating from incoming coil shape issues:

a) camber b) longitudinal bow c) twist d) flare e) center wave (center buckle) f) edge wave. H-66

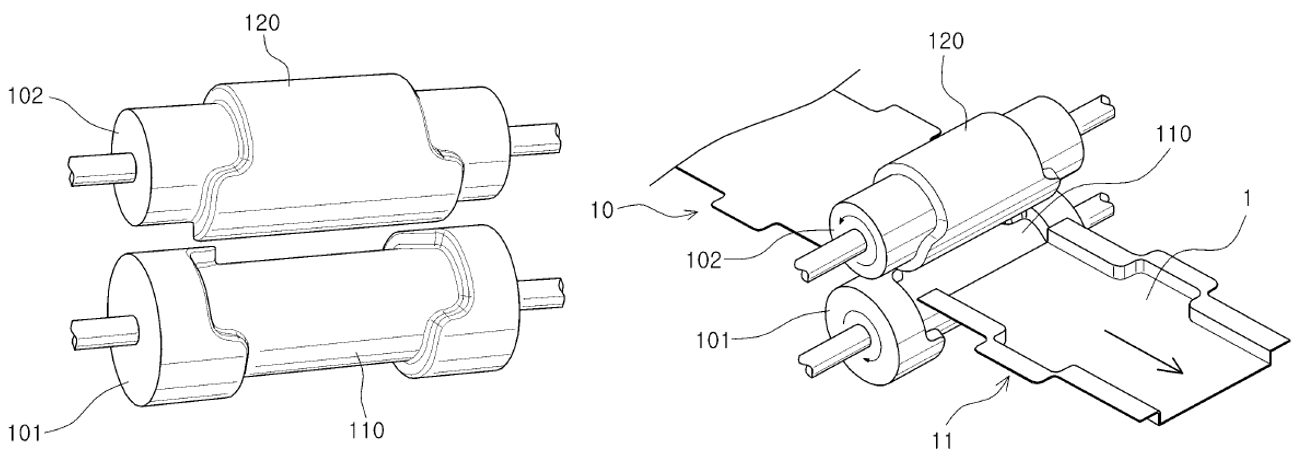

Roll Stamping

Traditional roll forming creates products with essentially uniform cross sections. A newer technique called Roll Stamping enhances the ability to create shapes and features which are not in the rolling axis.

Using a patented processA-48, R-9, forming rolls with the part shape along the circumferential direction creates the desired form, as shown in Figure 16.

Figure 16: Roll Stamping creates additional shapes and features beyond capabilities of traditional roll forming. A-48

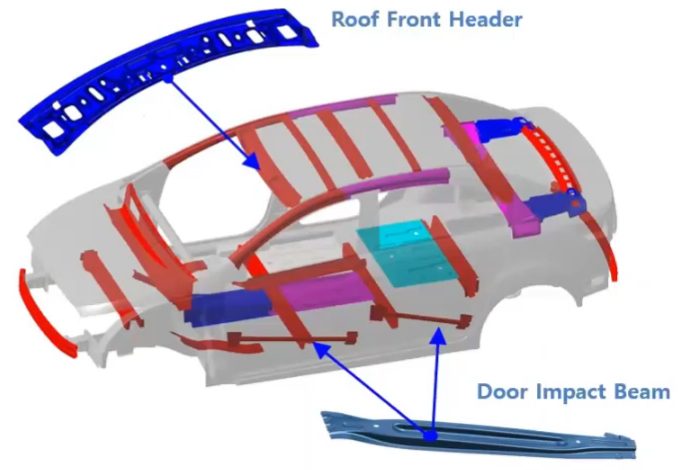

This approach can be applied to a conventional roll forming line. In the example of an automotive door impact beam, the W-shaped profile in the central section and the flat section which attaches to the door inner panel are formed at the same time, without the need for brackets or internal spot welds (Figure 17). Sharp corner curvatures are possible due to the incremental bending deformation inherent in the process.

Figure 17: A roll stamped door part formed on a conventional roll forming line eliminates the need for welding brackets at the edges.R-9

A global automaker used this method to replace a three-piece door impact beam made with a 2.0 mm PHS-CR1500T-MB press hardened steel tube requiring 2 end brackets formed from 1.4 mm CR-500Y780T-DP to attach it to the door frame, shown in Figure 18. The new approach, with a one-piece roll stamped 1.0 mm CR900Y1180T-CP complex phase steel impact beam, resulted in a 10% weight savings and 20% cost savings.K-58 This technique started in mass production on a Korean sedan in 2017, a Korean SUV in 2020, and a European SUV in 2021.K-58

Figure 18: Some Roll Stamping Automotive Applications.K-58

Thanks are given to Brian Oxley, Product Manager, Shape Corporation, for his contributions to the Roll Forming Case Study and Coil Shape Imperfections section. Brian Oxley is a Product Manager in the Core Engineering team at Shape Corp. Shape Corp. is a global, full-service supplier of lightweight steel, aluminum, plastic, composite and hybrid engineered solutions for the automotive industry. Brian leads a team responsible for developing next generation products and materials in the upper body and closures space that complement Shape’s core competency in roll forming. Brian has a Bachelor of Science degree in Material Science and Engineering from Michigan State University.

Thanks are given to Brian Oxley, Product Manager, Shape Corporation, for his contributions to the Roll Forming Case Study and Coil Shape Imperfections section. Brian Oxley is a Product Manager in the Core Engineering team at Shape Corp. Shape Corp. is a global, full-service supplier of lightweight steel, aluminum, plastic, composite and hybrid engineered solutions for the automotive industry. Brian leads a team responsible for developing next generation products and materials in the upper body and closures space that complement Shape’s core competency in roll forming. Brian has a Bachelor of Science degree in Material Science and Engineering from Michigan State University.

![Considerations When Deciding Whether to Cold Form or Hot Form]()

Tube Forming

Manufacturing precision welded tubes typically involves continuous roll forming followed by a longitudinal weld typically created by high frequency (HF) induction welding process known as electric resistance welding (ERW) or by laser welding.

Tubular components can be a cost-effective way to reduce vehicle mass and improve safety. Closed sections are more rigid, resulting in improved structural stiffness. Automotive applications include seat structures, cross members, side impact beams, bumpers, engine subframes, suspension arms, and twist beams. All AHSS grades can be roll formed and welded into tubes with large D/t ratios (tube diameter / wall thickness); tubes having 100:1 D/t with a 1mm wall thickness are available for Dual Phase and TRIP grades.

Figure 1: Automotive Applications for Tubular Components.A-35

As roll formed and welded tubes are used with mounting brackets and little else in some Side Intrusion Beams (Figure 2), or they can be used as a precursor to hydroforming, such as the Engine Cradle shown in Figure 3.

Figure 2: Side intrusion beams made from a welded tube with mounting brackets.S-34

Figure 3: The stages of a Hydroformed Engine Cradle: A) Straight Tube, B) After bending; C) After pre-forming; D) Hydroformed Engine Cradle. S-35

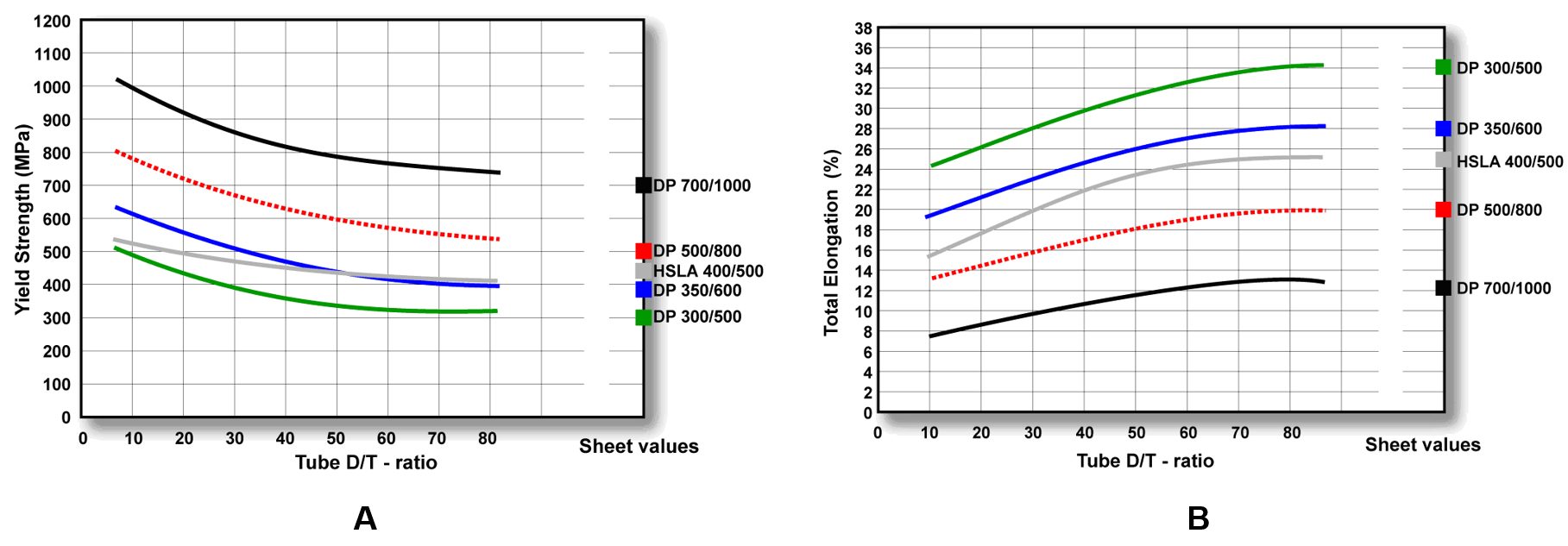

The processing steps of tube manufacturing affect the mechanical properties of the tube, increasing the yield strength and tensile strength, while decreasing the total elongation. Subsequent operations like flaring, flattening, expansion, reduction, die forming, bending and hydroforming must consider the tube properties rather than the properties of the incoming flat sheet.

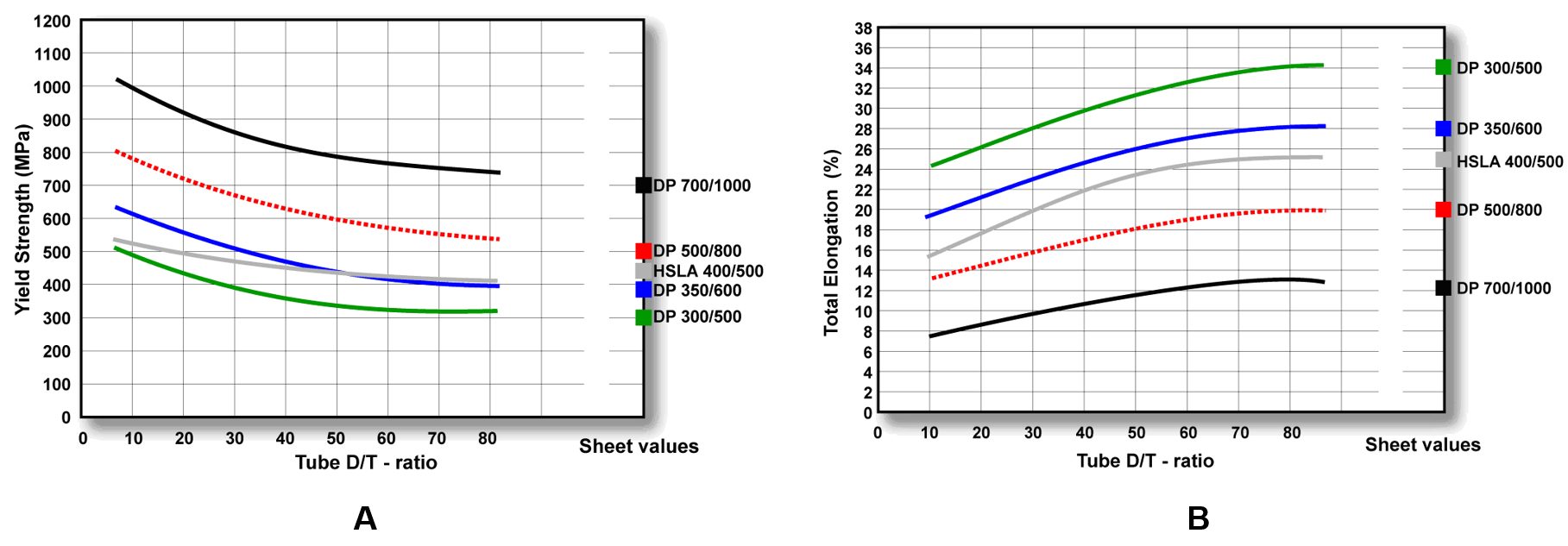

The work hardening, which takes place during the tube manufacturing process, increases the yield strength and makes the welded AHSS tubes appropriate as a structural material. Mechanical properties of welded AHSS tubes (Figure 4) show welded AHSS tubes provide excellent engineering properties. AHSS tubes are suitable for structures and offer competitive advantage through high-energy absorption, high strength, low weight, and cost efficient manufacturing

Figure 4: Anticipated Properties of AHSS Tubes; A) Yield Strength, B) Total Elongation.R-1

The degree of work hardening, and consequently the formability of the tube, depends both on the steel grade and the tube diameter/thickness ratio (D/T) as shown in Figure 5. The degree of work hardening influences the reduction in formability of tubular materials compared with the as-produced sheet material. Furthermore, computerized forming-process development utilizes the actual true stress-true strain curve of steel taken from the tube, which is influenced by the steel grade, tube diameter, and forming process.

Figure 5: Examples of true stress – true strain curves for AHSS tubes made from Dual Phase Steel with 590 MPa minimum tensile strength.A-36

Bending AHSS tubes follows the same laws that apply to ordinary steel tubes. Splitting, buckling, and wrinkling must all be avoided. As wall thickness and bend radius decrease, the potential for wrinkling or buckling increases.

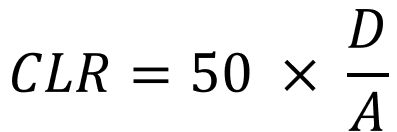

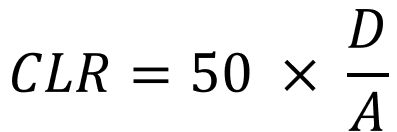

One method to evaluate the formability of a tube is the minimum bend radius. An empirically derived formulaS-36 for the minimum Centerline Radius (CLR) considers both tube diameter (D) and total elongation (A) determined in a tensile test with a proportional test specimen, and assumes tube formation via rotary draw bending:

The formula shows that a bending radius equal to the tube diameter (1xD) requires a steel with 50% elongation. Successfully bending low elongation material needs a greater bend radius. Consider, for example, a dual phase steel grade where the elongation of a sample measured off the tube is 12.5%. Here, the minimum bend radius is 4 times the tube diameter. The tube bending method, the use and type of mandrels, and choice of lubrication may all affect the CLR.

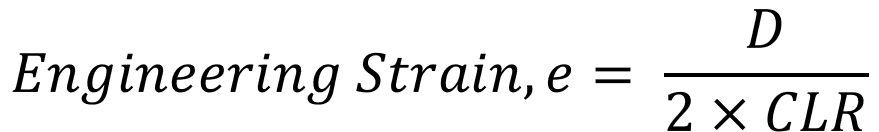

The engineering strain on the outer surface can be estimated as the tube diameter (D) divided by twice the Centerline Radius (CLR):

For example, if you are bending a 40 mm diameter tube around a centerline radius of 100mm, the engineering strain on the outer surface is approximately 40/[2*100] = 20%. As a rough estimate, successful bending requires the tube to have a minimum elongation value from a tensile test in excess of this amount. Otherwise, a larger radius or modifications to the forming process is needed.

Springback is related to the elastic behavior of the tube. Yield strength variation between production batches can lead to variation in the amount of springback. A rule of thumb is that a variation of ± 10 MPa in yield strength causes a variation of approximately ± 0.1° in the bending radius. In addition, a high frequency weld which is harder and stronger than the base material causes a maximum of approximately ± 0.1° variation in bending radius.S-36

The bending behavior of tube depends on both the tubular material and the bending technique. The weld seam is also an area of non-uniformity in the tubular cross section, and therefore influences the forming behavior of welded tubes. The recommended procedure is to locate the weld area in a neutral position during the bending operation.

Figures 6 and 7 provide examples of the forming of AHSS tubes. The discussion on Tailored Products describes tailored tubes, which may be further hydroformed.

Figure 6: DP steel bent to 45 degrees with centerline bending radius of 1.5xD using booster bending. Steel properties in the tube: 610 MPa yield strength, 680 MPa tensile strength, 27% total elongation. R-1

Figure 7: Hydroformed Engine Cradle made from a dual phase steel welded tube by draw bending with centerline bending radius of 1.6xD and a bending angle greater than 90 degrees. Steel properties in the tube: 540 MPa yield strength, 710 MPa tensile strength, 34% total elongation. R-1

Key Points

- Due to the cold working generated during tube forming, the formability of the tube is reduced compared to the as-received sheet.

- The work hardening during tube forming increases the YS and TS, thereby allowing the tube to be a structural member.

- Successful bending requires aligning the targeted radii with the available elongation of the selected steel grade.

- The weld seam should be located at the neutral axis of the tube, whenever possible during the bending operation.

Thanks are given to

Thanks are given to