![Considerations When Deciding Whether to Cold Form or Hot Form]()

Automakers contemplating whether a part is cold stamped or hot formed must consider numerous ramifications impacting multiple departments. The considerations below relative to cold stamping are applicable to any forming operation occurring at room temperature such as roll forming, hydroforming, or conventional stamping. Similarly, hot stamping refers to any set of operations using Press Hardening Steels (or Press Quenched Steels), including those that are roll formed or fluid-formed.

Equipment

There is a well-established infrastructure for cold stamping. New grades benefit from servo presses, especially for those grades where press force and press energy must be considered. Larger press beds may be necessary to accommodate larger parts. As long as these factors are considered, the existing infrastructure is likely sufficient.

Progressive-die presses have tonnage ratings commonly in the range of 630 to 1250 tons at relatively high stroke rates. Transfer presses, typically ranging from 800 to 2500 tons, operate at relatively lower stroke rates. Power requirements can vary between 75 kW (630 tons) to 350 kW (2500 tons). Recent transfer press installations of approximately 3000 tons capacity allow for processing of an expanded range of higher strength steels.

Hot stamping requires a high-tonnage servo-driven press (approximately 1000 ton force capacity) with a 3 meter by 2 meter bolster, fed by either a roller-hearth furnace more than 30 m long or a multi-chamber furnace. Press hardened steels need to be heated to 900 °C for full austenitization in order to achieve a uniform consistent phase, and this contributes to energy requirements often exceeding 2 MW.

Integrating multiple functions into fewer parts leads to part consolidation. Accommodating large laser-welded parts such as combined front and rear door rings expands the need for even wider furnaces, higher-tonnage presses, and larger bolster dimensions.

Blanking of coils used in the PHS process occurs before the hardening step, so forces are low. Post-hardening trimming usually requires laser cutting, or possibly mechanical cutting if some processing was done to soften the areas of interest.

That contrasts with the blanking and trimming of high strength cold-forming grades. Except for the highest strength cold forming grades, both blanking and trimming tonnage requirements are sufficiently low that conventional mechanical cutting is used on the vast majority of parts. Cut edge quality and uniformity greatly impact the edge stretchability that may lead to unexpected fracture.

Responsibilities

Most cold stamped parts going into a given body-in-white are formed by a tier supplier. In contrast, some automakers create the vast majority of their hot stamped parts in-house, while others rely on their tier suppliers to provide hot stamped components. The number of qualified suppliers capable of producing hot stamped parts is markedly smaller than the number of cold stamping part suppliers.

Hot stamping is more complex than just adding heat to a cold stamping process. Suppliers of cold stamped parts are responsible for forming a dimensionally accurate part, assuming the steel supplier provides sheet metal with the required tensile properties achieved with a targeted microstructure.

Suppliers of hot stamped parts are also responsible for producing a dimensionally accurate part, but have additional responsibility for developing the microstructure and tensile properties of that part from a general steel chemistry typically described as 22MnB5.

Property Development

Independent of which company creates the hot formed part, appropriate quality assurance practices must be in place. With cold stamped parts, steel is produced to meet the minimum requirements for that grade, so routine property testing of the formed part is usually not performed. This is in contrast to hot stamped parts, where the local quench rate has a direct effect on tensile properties after forming. If any portion of the part is not quenched faster than the critical cooling rate, the targeted mechanical properties will not be met and part performance can be compromised. Many companies have a standard practice of testing multiple areas on samples pulled every run. It’s critical that these tested areas are representative of the entire part. For example, on the top of a hat-section profile where there is good contact between the punch and cavity, heat extraction is likely uniform and consistent. However, on the vertical sidewalls, getting sufficient contact between the sheet metal and the tooling is more challenging. As a result, the reduced heat extraction may limit the strengthening effect due to an insufficient quench rate.

Grade Options for Cold Stamped or Hot Formed Steel

There are two types of parts needed for vehicle safety cage applications: those with the highest strength that prevent intrusion, and those with some additional ductility that can help with energy absorption. Each of these types can be achieved via cold stamping or hot stamping.

When it comes to cold stamped parts, many grade options exist at 1000 MPa that also have decent ductility. The advent of the 3rd Generation Advanced High Strength Steels adds to the tally – the stress-strain curve of a 3ʳᵈ Gen QP980 steel is presented in Figure 1. Most of these top out at 1200 MPa, with some companies offering cold-formable Advanced High Strength Steels with 1400 or 1500 MPa tensile strength. The chemistry of AHSS grades is a function of the specific characteristics of each production mill, meaning that OEMs must exercise diligence when changing suppliers.

Figure 1: Stress-strain curve of industrially produced QP980.W-35

Martensitic grades from the steel mill have been in commercial production for many years, with minimum strength levels typically ranging from 900 MPa to 1470 MPa, depending on the grade. These products are typically destined for roll forming, except for possibly those at the lower strengths, due to limited ductility. Until recently, MS1470, a martensitic steel with 1470 MPa minimum tensile strength, was the highest strength cold formable option available. New offerings from global steelmakers now include MS1700, with a 1700 MPa minimum tensile strength, as well as MS 1470 with sufficient ductility to allow for cold stamping. Automakers have deployed these grades in cold stamped applications such as crossmembers and roof reinforcements, with some applications shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2: Cold-Stamped Martensitic Steel with 1500 MPa Tensile Strength used in the Nissan B-Segment Hatchback.K-57

Until these recent developments, hot stamping was the primary option to reach the highest strength levels in part shapes having even mild complexity. Under proper conditions, a chemistry of 22MnB5 could routinely reach a nominal or aim strength of 1500 MPa, which led to this grade being described as PHS1500, CR1500T-MB, or with similar nomenclature. Note that in this terminology, 1500 MPa nominal strength typically corresponds to a minimum strength of 1300 MPa.

The 22MnB5 chemistry is globally available, but the coating approaches discussed below may be company-specific.

Newer PHS options with a modified chemistry and subsequent processing differences can reach nominal strength levels of 2000 MPa. Other options are available with additional ductility at strength levels of 1000 MPa or 1200 MPa. A special class called Press Quenched Steels have even higher ductility with strength as low as 450 MPa.

The spectrum of grades available for cold-stamped and hot formed steel parts allows automakers to fine-tune the crash energy management features within a body structure, contributing to steel’s “infinite tune-ability” capability which gives automotive engineers design flexibility and freedoms not available from other structural materials.

Corrosion Protection

Uncoated versions of a grade must take a different chemistry approach than the hot dip galvanized (GI) or hot dipped galvannealed (HDGA) versions since the hot dip galvanizing process (Figure 3) acts as a heat treatment cycle that changes the properties of the base steel. Steelmakers adjust the base steel chemistry to account for this heat treatment to ensure the resultant properties fall within the grade requirements.

Figure 3: Schematic of a typical hot-dipped galvanizing line with galvanneal capability.

This strategy has limitations as it relates to grades with increasing amounts of martensite in the microstructure. Complex thermal cycles are needed to produce the highly engineered microstructures seen in advanced steels. Above a certain strength level, it is not possible to create a GI or HDGA version of that grade.

For example, when discussing fully martensitic grades from the steel mill, hot dip galvanizing is not an option. If a martensitic grade needs corrosion protection, then electrogalvanizing (Figure 4) is the common approach since an EG coating is applied at ambient temperature, which is low enough to avoid negatively impacting the properties. Automakers might choose to forgo a galvanized coating if the intended application is in a dry area that is not exposed to road salt.

Figure 4: Schematic of an electrogalvanizing line.

For press hardening steels, coatings serve multiple purposes. Without a coating, uncoated steels will oxidize in the austenitizing furnace and develop scale on the surface. During hot stamping, this scale layer limits efficient thermal transfer and may prevent the critical cooling rate from being reached. Furthermore, scale may flake off in the tooling, leading to tool surface damage. Finally, scale remaining after hot stamping is typically removed by shot blasting, an off-line operation that may induce additional issues.

Using a hot dip galvanized steel in a conventional direct press hardening process (blank -> heat -> form/quench) may contribute to liquid metal embrittlement (LME). Getting around this requires either changing the steel chemistry from the conventional 22MnB5 or using an indirect press hardening process that sees the bulk of the part shape formed at ambient temperatures followed by heating and quenching.

Those companies wishing to use the direct press hardening process can use a base steel having an aluminum-silicon (Al-Si) coating, providing that the heating cycle in the austenitizing furnace is such that there is sufficient time for alloying between the coating and the base steel. Welding practices using these coated steels need to account for the aluminum in the coating, but robust practices have been developed and are in widespread use.

Setting Correct Welding Parameters for Resistance Spot Welding

Specific welding parameters need to be developed for each combination of material type and thickness. In general, Press Hardening Steels require more demanding process conditions. One important factor is electrode force, which is typically higher than needed to weld cold formed steels of the same thickness. The actual recommended force depends on the strength level and the thickness of the steel. Of course, strength and thickness affects the welding machine/welding gun force capability requirement.

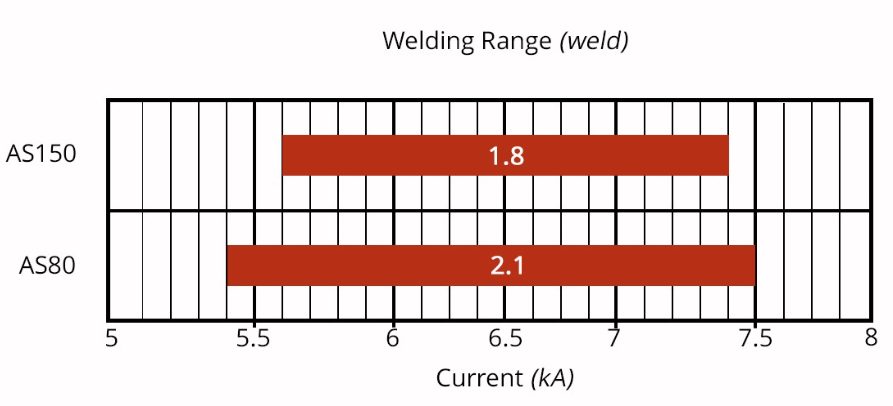

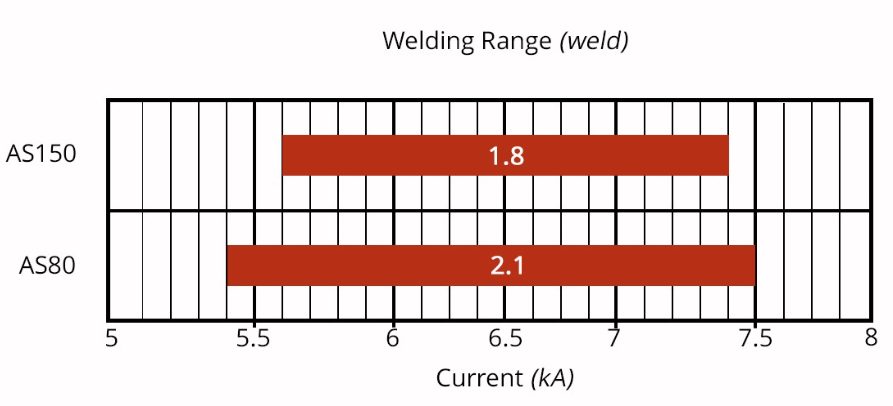

The welding current level, and more importantly, the current range are both important. The current range is one of the best indicators of welding process robustness, so it is sometimes described as the welding process window. Figure 5 indicates the relative range of current required for spot welding different steel types. A smaller process window may require more frequent weld quality evaluations, such as for adequate weld size, necessitating more frequent corrective actions to address the discovered quality concern.

Figure 5: Relative Current Range (process windows) for Different Steel Types

Effect of Coating Type on Weldability

When resistance spot welding coated steels, the coating must be removed from the weld area during and in the beginning of the weld cycle to allow a steel-to-steel weld to occur. The combination of welding current, weld time, and electrode force are responsible for this coating displacement.

For all coated steels, the ability of the coating to flow is a function of the coating type and properties such as electrical resistivity and melting point, as well as the coating thickness.

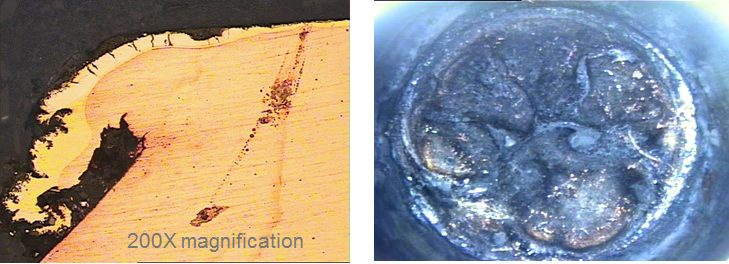

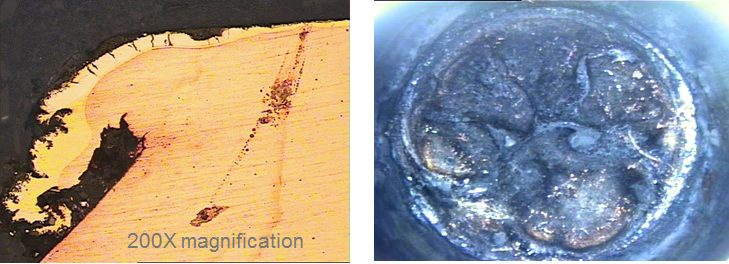

Cross sectioned spot welds made on press hardened steel with different coating weights of an Aluminum -Silicon coating is presented in Figure 6. Note the displaced coating at the periphery of weld. Figure 7 shows the difference in current range required to produce acceptable welds associated with these different coating weights. The thicker coating shows a smaller current range. In addition, the press-hardened Al-Si coating has a much higher melting point than the zinc coatings typically found on cold stamped steels, making it more difficult to displace from the weld area.

Figure 6: Aluminum -Silicon coated press hardened steels.O-16

Figure 7: Influence of Aluminum-Silicon coating weight on welding range.O-16

Liquid Metal Embrittlement and Resistance Spot Welding

Cold-formable, coated, Advanced High Strength Steels are widely used in automotive applications. One welding issue these materials encounter is increased hardness in the weld area, that may result in brittle fracture of the weld. Another issue is their sensitivity to Liquid Metal Embrittlement (LME) cracking.

Both issues are discussed in detail in the Joining section of the WorldAutoSteel AHSS Guidelines website and the WorldAutoSteel Phase 2 Report on LME.

Resistance Spot Welding Using Current Pulsation

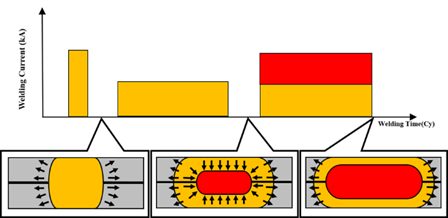

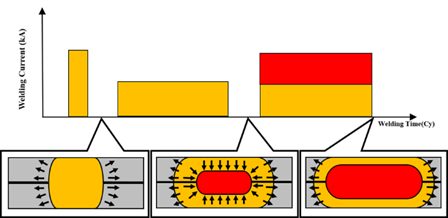

The most effective solution for these issues is using current pulsation during the welding cycle, schematically described in Figure 8.

Figure 8: Nugget growth differences in Single Pulse vs. Multi-Pulse Welding

Pulsation of the current allows much better control of the heat generation and weld nugget development. Pulsation variables include the number of pulses (typically 2 to 4), current, time for each pulse, and the cool time between the pulses.

Pulsation during Resistance Spot Welding is beneficial for press hardening steels, coated cold stamped steels of all grades, and multi-material stack-ups. Information about multi-sheet, multi-material stack-ups can be – as described in our articles on 3T/4T and 5T Stack-Ups

For more information about PHS grades and processing, see our Press Hardened Steel Primer.

Thanks are given to Eren Billur, Ph.D., Billur MetalForm for his contributions to the Equipment section, as well as many of the webpages relating to Press Hardening Steels at www.AHSSinsights.org.

Blog, homepage-featured-top, main-blog

Equipment, Responsibilities, and Property Development Considerations When Deciding How A Part Gets Formed

Automakers contemplating whether a part is cold stamped or hot formed must consider numerous ramifications impacting multiple departments. Over a series of blogs, we’ll cover some of the considerations that must enter the discussion.

The discussions relative to cold stamping are applicable to any forming operation occurring at room temperature such as roll forming, hydroforming, or conventional stamping. Similarly, hot stamping refers to any set of operations using Press Hardening Steels (or Press Quenched Steels), including those that are roll formed or fluid-formed.

Equipment

There is a well-established infrastructure for cold stamping. New grades benefit from servo presses, especially for those grades where press force and press energy must be considered. Larger press beds may be necessary to accommodate larger parts. As long as these factors are considered, the existing infrastructure is likely sufficient.

Progressive-die presses have tonnage ratings commonly in the range of 630 to 1250 tons at relatively high stroke rates. Transfer presses, typically ranging from 800 to 2500 tons, operate at relatively lower stroke rates. Power requirements can vary between 75 kW (630 tons) to 350 kW (2500 tons). Recent transfer press installations of approximately 3000 tons capacity allow for processing of an expanded range of higher strength steels.

Hot stamping requires a high-tonnage servo-driven press (approximately 1000 ton force capacity) with a 3 meter by 2 meter bolster, fed by either a roller-hearth furnace more than 30 m long or a multi-chamber furnace. Press hardened steels need to be heated to 900 °C for full austenitization in order to achieve a uniform consistent phase, and this contributes to energy requirements often exceeding 2 MW.

Integrating multiple functions into fewer parts leads to part consolidation. Accommodating large laser-welded parts such as combined front and rear door rings expands the need for even wider furnaces, higher-tonnage presses, and larger bolster dimensions.

Blanking of coils used in the PHS process occurs before the hardening step, so forces are low. Post-hardening trimming usually requires laser cutting, or possibly mechanical cutting if some processing was done to soften the areas of interest.

That contrasts with the blanking and trimming of high strength cold-forming grades. Except for the highest strength cold forming grades, both blanking and trimming tonnage requirements are sufficiently low that conventional mechanical cutting is used on the vast majority of parts. Cut edge quality and uniformity greatly impact the edge stretchability that may lead to unexpected fracture.

Responsibilities

Most cold stamped parts going into a given body-in-white are formed by a tier supplier. In contrast, some automakers create the vast majority of their hot stamped parts in-house, while others rely on their tier suppliers to provide hot stamped components. The number of qualified suppliers capable of producing hot stamped parts is markedly smaller than the number of cold stamping part suppliers.

Hot stamping is more complex than just adding heat to a cold stamping process. Suppliers of cold stamped parts are responsible for forming a dimensionally accurate part, assuming the steel supplier provides sheet metal with the required tensile properties achieved with a targeted microstructure.

Suppliers of hot stamped parts are also responsible for producing a dimensionally accurate part, but have additional responsibility for developing the microstructure and tensile properties of that part from a general steel chemistry typically described as 22MnB5.

Property Development

Independent of which company creates the hot formed part, appropriate quality assurance practices must be in place. With cold stamped parts, steel is produced to meet the minimum requirements for that grade, so routine property testing of the formed part is usually not performed. This is in contrast to hot stamped parts, where the local quench rate has a direct effect on tensile properties after forming. If any portion of the part is not quenched faster than the critical cooling rate, the targeted mechanical properties will not be met and part performance can be compromised. Many companies have a standard practice of testing multiple areas on samples pulled every run. It’s critical that these tested areas are representative of the entire part. For example, on the top of a hat-section profile where there is good contact between the punch and cavity, heat extraction is likely uniform and consistent. However, on the vertical sidewalls, getting sufficient contact between the sheet metal and the tooling is more challenging. As a result, the reduced heat extraction may limit the strengthening effect due to an insufficient quench rate.

For more information, see our Press Hardened Steel Primer to learn more about PHS grades and processing!

Thanks are given to Eren Billur, Ph.D., Billur MetalForm for his contributions to the Equipment section, as well as many of the webpages relating to Press Hardening Steels at www.AHSSinsights.org.

Danny Schaeffler is the Metallurgy and Forming Technical Editor of the AHSS Applications Guidelines available from WorldAutoSteel. He is founder and President of Engineering Quality Solutions (EQS). Danny wrote the monthly “Science of Forming” and “Metal Matters” column for Metalforming Magazine, and provides seminars on sheet metal formability for Auto/Steel Partnership and the Precision Metalforming Association. He has written for Stamping Journal and The Fabricator, and has lectured at FabTech. Danny is passionate about training new and experienced employees at manufacturing companies about how sheet metal properties impact their forming success.

![Considerations When Deciding Whether to Cold Form or Hot Form]()

Coatings

Friction during the stamping process is a key variable which impacts metal flow. It varies across the stamping based on local conditions like geometry, pressure, and lubrication, which change during the forming process. The tool surface influences metal flow, as seen when comparing the results of uncoated tools to those with chrome plating or PVD coatings.

The sheet steel surface is another contributor to friction and metal flow, which changes based on the type of galvanized coating. There are different types of friction tests which attempt to replicate different portions of the forming process, such as flow through draw beads of drawing under tension. Since these tests measure friction under different conditions, the numerical results for the coefficient of friction are not directly comparable. However, within a specific test, extracting useful information is possible.

A study S-54 evaluated the friction of seven deep-drawing steels (DDS), all between 0.77mm and 0.84 mm, with the coating being the most significant difference between the products. Table 1 shows the sample identification and lists the mechanical and coating properties of the tested products, which included two electrogalvanized (EG), one electrogalvanized Zn-Fe alloy (EGA), two hot dip galvanized (HDGI), and two hot dip galvanneal (HDGA) steels. The HDGA coatings differed in the percentage of zeta phase relative to delta phase in the coatings.

Table 1: Properties of DDS grades used in this friction study.S-54

Tests to evaluate friction included a Draw Bead Simulator (DBS), a Bending Under Tension (BUT) test, and a Stretch Forming Simulator (SFS) test. Dome height test and deep draw cup tests were performed to verify the friction behavior of the tested materials. Citation S-54 explains these tests in greater detail. Two different lubrication conditions were evaluated: “as” meaning as-received, and “lub” where the samples were initially cleaned with acetone and mill oil was reapplied.

Figure 1 summarizes the results from the three different friction tests. The relative performance of different coatings is consistent across the tests.S-54 For the tested materials, the HDGI coated steels showed the lowest average friction coefficient and a more stable friction behavior regardless of the lubrication conditions. Zn-Fe alloy coatings (EGA or HDGA) typically resulted in the highest friction. The BUT test generates the lowest strain level among three tests, while the DBS and SFS tests result in higher strain due to a more severe surface contact between tooling and specimen. Stretch forming test tends to result a lower friction coefficient mainly due to higher strain in the stretching process.

Figure 1: Friction test results for different coatings. The relative performance of different coatings is consistent across the tests. S-54

Coating and lubrication interact to influence friction. Draw bead simulator testing compared friction generated on 1mm cold rolled (bare), hot dip galvanized (HDG), and electrogalvanized (EG) deep drawing steel, lubricated with varying amounts of either mill oil, prelube, or a combination of the lubricantsS-68, as summarized in Figures 2, 3, and 4.

Conclusions from this study include:

- Prelube reduces friction on all tested surfaces, with the most dramatic effect seen on electrogalvanized surfaces.

- Above 1 g/m2, there is little friction benefit associated with adding additional lubrication.

- Adding heavier amounts of prelube on top of mill oil did incrementally reduce friction, but the effect essentially maximized at 1.5 g/m2 prelube on top of 1 g/m2 mill oil.

- Cold rolled (bare) steel showed a greater tolerance for dry spots than hot dip or electrogalvanized surfaces. Areas without any lubricant on HDG or EG surfaces led to sample fracture.

Figure 2: DBS Coefficient of Friction: Cold Rolled (Bare) Mild Steel.S-68

Figure 3: DBS Coefficient of Friction: Hot Dip Galvanized Mild Steel.S-68

Figure 4: DBS Coefficient of Friction: Electrogalvanized Mild Steel.S-68

The tool material influences metal flow and therefore friction, but its effect varies with the zinc coating on the sheet steel. The impact of tool steel, kirksite zinc, cast iron, cast steel and chrome plated cast iron on different coated deep drawing steels was evaluated using the Bending Under Tension test.S-55 The friction coefficient obtained using kirksite is lower than that obtained with the other die materials and is relatively independent of the type of zinc coating (Figure 5), reinforcing the caution usually applied stating that soft tool tryout will not be fully representative of what occurs later in the die development process. Supporting the conclusions of the prior study, this evaluation also showed that the HDGI coating tends to have the lowest friction coefficient, especially for cast iron with and without chrome plating (hard tool and production). Also observed was that an oil-based blankwash solution tends to have the highest friction coefficient among the tested lubricants, while a dry film has the lowest friction coefficient.

Figure 5: Influence of die material on friction of galvanized DDS determined in the Bending Under Tension test.S-55

The surface phase in hot dipped galvannealed steel has a impact on friction. Whereas the surface of hot dip galvanized steel is essentially pure zinc, the GA surface may be zeta phase or delta phase. The iron content is the primary compositional difference: the zeta (ζ) phase contains approximately 5.2% to 6.1% by weight of iron, and the delta (δ) phase contains approximately 7.0% to 11.5% by weight of iron.G-21 Zeta phase is softer and less brittle than the delta phase, but has a high coefficient of friction.G-22 Even with a fully delta phase surface, additional optimization is possible to produce targeted surface morphologies.S-56 The two right-most images in Figure 6 are both of delta phase surfaces, with the cubic surface (right image) associated with better formability than the rod surface of the center image (Figures 7 and 8).

Figure 6: Surface morphology and coating cross section of 3 galvanneal coatings. Left: Zeta surface; Center: Delta-rod surface; Right: Delta-cubic surface.S-56

Figure 7: Formability of galvannealed surfaces evaluated through a square cup test.S-56

Figure 8: Formability of galvannealed surfaces evaluated through a Limiting Draw Height (LDH) test. Higher is better.S-56

Low annealing temperature or time can result in excessive zeta phase. However, longer and hotter annealing cycles increase the risk of powdering and flaking. Producing the correct balance of ZnFe phases requires control of time and temperature of the galvannealing process.

![Considerations When Deciding Whether to Cold Form or Hot Form]()

Coatings

topofpage

Many formed parts require corrosion protection, achieved through the application of some type of zinc-based or aluminum-based coating. The primary methods of applying zinc are through a hot dipped galvanizing line, or through an electro-galvanizing process. Aluminum-based coatings are applied in a hot dipped aluminizing line.

Both aluminized and galvanized coatings provide a barrier layer preventing corrosion of the underlying sheet steel. Zinc-based coatings also provide galvanic protection, where the zinc acts as a sacrificial anode if scratches or impact damage the coating, and therefore corrodes first before the underlying steel.

Aluminum melts at a higher temperature than zinc, which is why aluminized steels are more frequently used in applications requiring corrosion protection at elevated temperatures such as those found in the engine compartment and in the exhaust system. There are two types of aluminized coatings, known as Type 1 (aluminum with 9% silicon) and Type 2 (pure aluminum). The aluminum-silicon AlSi coating associated with press hardening steels are these Type 1 aluminized coatings. There are limited automotive applications for Type 2 pure aluminum coatings.

Zinc-magnesium coatings are relatively new options, offering enhanced cut edge corrosion protection, with lower friction and lower risk of galling and powdering than other common zinc coatings.

Most hot dipped galvanized lines produce surfaces which result in similar coefficients of friction for a given steel type. Different electrogalvanized coating lines may result in different surface morphologies, which can result in significantly different formability characteristics.

Passing a pure zinc-coated steel through a furnace allows the steel and zinc to inter-diffuse and results in an alloyed coating known as galvanneal. Hot dipped galvannealed coatings have improved joining due to the iron in the coating. Unlike the uniform coating composition associated with hot dip galvanized and electrogalvanized coatings, GA coatings are composed of different phases with varying composition. This may lead to different forming, joining, and painting characteristics when comparing products produced on different lines.

Differences in performance due to coating line characteristics is another reason why it is good practice to Identify the intended steel production source early in the die construction and die try-out process. Tryout material should come from the same source as will supply production.

Hot Dipped Galvanized and Galvannealed Coatings

The majority of sheet steel parts on a vehicle require corrosion protection, independent of whether they are made from mild or high strength steel and whether they are intended for exposed or unexposed applications. Hot dipped galvanizing – applying a zinc coating over the steel – is the most common way to achieve corrosion protection. It is an economical solution, since cold rolled steel can be annealed and coated in the same continuous operation.

A typical in-line continuous hot dip galvanizing line such as that shown in Figure 1 uses a full-hard cold rolled steel coil as the feedstock. Welding individual coils together produces a continuous strip. After cleaning, the strip is processed in a continuous annealing furnace where the microstructure is recrystallized, improving forming characteristics. Adjustments to the annealing temperature produces the desired microstructure associated with the ordered grade. Rather than cooling to room temperature, the in-process coil is cooled to just above 460 °C (860 °F), the temperature of the molten zinc bath it enters. The chemistry in the zinc pot is a function of whether a hot dipped galvanized or galvannealed coating is ordered. Hot rolled steels may be coated with the hot dip galvanizing process, but different processing conditions are used to achieve the targeted properties.

Figure 1: Schematic of a typical hot dipped galvanizing line with galvanneal capability.

There are several types of hot dipped coatings for automotive applications, with unique characteristics that affect their corrosion protection, lubricity for forming, weldability and paintability. One of the primary hot dipped galvanized coatings is a pure zinc coating (abbreviated as GI), sometime referred to as free zinc. The molten zinc bath has small amounts of aluminum which helps to form a thin Fe2Al5 layer at the zinc-steel interface. This thin barrier layer prevents zinc from diffusing into the base steel, which leaves the coating as essentially pure zinc.

Coils pass through the molten zinc at speeds up to 3 meters per second. Zinc coating weight is controlled by gas knives (typically air or nitrogen) blowing off excess liquid zinc as the coil emerges from the bath. Zinc remaining on the surface solidifies into crystals called spangle. Molten zinc chemistry and cooling practices used at the galvanizing line control spangle size. In one extreme, a large spangle zinc coating is characteristic of garbage cans and grain silos. In the other extreme, the zinc crystal structure is sufficiently fine that it is not visible to the unaided eye. Since spangle can show through on a painted surface, a minimum-spangle or no-spangle option is appropriate for surface-critical applications.

The other primary hot dipped coating used for corrosion protection is hot dipped galvanneal (abbreviated as GA). Applying this coating to a steel coil involves the same steps as creating a free zinc hot dipped coated steel, but after exiting the zinc pot, the steel strip passes through a galvannealing furnace where the zinc coating is reheated while still molten.

The molten zinc bath used to produce a GA coating has a lower aluminum content than what is used to produce a GI coating. Without aluminum to create the barrier layer, the zinc coating and the base steel inter-diffuse freely, creating an iron-zinc alloy with typical average iron content in the 8% to 12% range. The iron content improves weldability, which is a key attribute of the galvanneal coatings.

The iron content is unevenly distributed throughout the coating, ranging from 5% at the surface (where the sheet metal coating contacts the tool surface during forming) to as much as 25% iron content at the steel/coating interface. The amount of iron at the surface and distribution within the coating is a function of galvannealing parameters and practices – primarily the bath composition and time spent at the galvannealing temperature. Coating iron content impacts coating hardness, which affects the interaction with the sheet forming lubricant and tools, and results in changes in friction. The hard GA coatings have a greater powdering tendency during contact with tooling surfaces, especially during movement through draw beads. Powdering is minimized by using thinner coatings – where 50 g/m2 to 60 g/m2 (50G to 60G) is a typical EG and GI coating weight, GA coatings are more commonly between 30 g/m2 to 45 g/m2 (30A to 45A)

Options to improve formability on parts made from GA coated steels include use of press-applied lubricants or products that can be applied at the steel mill after galvanizing, like roll-coated phosphate, which have the additional benefit of added lubricity. The surface morphology of a galvannealed surface (Figure 2) promotes good phosphate adherence, which in turn is favorable for paintability.

Figure 2: High magnification photograph of a galvannealed steel surface. The surface structure results in excellent paint adhesion.

Galvannealed coatings provides excellent corrosion protection to the underlying steel, as do GI and EG coatings. GI and EG coatings are essentially pure zinc. Zinc acts as a sacrificial anode if scratches or impact damages either coating, and therefore will corrode first before the underlying steel. The corrosion product of GI and EG is white, and is a combination of zinc carbonate and zinc hydroxide. A similar mechanism protects GA coated steels, but the presence of iron in the coating may result in a reddish tinge to the corrosion product. This should not be interpreted as an indication of corrosion of the steel substrate.

Another option is to change the bath composition such that it contains proper amounts of aluminum and magnesium. The results in a zinc-magnesium (ZM) coating, which has excellent cut edge corrosion protection.

Producing galvanized and galvannealed Advanced High Strength Steels is challenging due to the interactions of the necessary thermal cycles at each step. As an example, the targeted microstructure of Dual Phase steels can be achieved by varying the temperature and time the steel strip passes through the zinc bath, and can be adjusted to achieve the targeted strength level. However, not all advanced high strength steels can attain their microstructure with the thermal profile of a conventional hot dipped galvanizing line with limited rapid quenching capabilities. In addition, many AHSS grades have chemistries that lead to increased surface oxides, preventing good zinc adhesion to the surface. These grades must be produced on a stand-alone Continuous Annealing Line, or CAL, without an in-line zinc pot. Continuous Annealing Lines feature a furnace with variable and rapid quenching operations that enable the thermal processing required to achieve very high strength levels. If corrosion protection is required, these steel grades are coated on an electrogalvanizing line (EG) in a separate operation, after being processed on a CAL line.

Hot dipped galvanizing lines at different steel companies have similar processes that result in similar surfaces with respect to coefficient of friction. Surface finish and texture (and resultant frictional characteristics) are primarily due to work roll textures, based on the customer specification. Converting from one coating line to another using the same specification is usually not of major significance with respect to coefficient of friction. A more significant change in friction is observed with changes between GI and GA and EG.

Electrogalvanized Coatings

Electrogalvanizing is a zinc deposition process, where the zinc is electrolytically bonded to steel in order to protect against corrosion. The process involves electroplating: running an electrical current through the steel strip as it passes through a saline/zinc solution.

Electrogalvanizing occurs at room temperature, so the microstructure, mechanical, and physical properties of AHSS products achieved on a continuous anneal line (CAL) are essentially unchanged after the electrogalvanizing (EG) process. EG lines have multiple plating cells, with each cell capable of being on or off. As a result, chief advantages of electrogalvanizing compared to hot dipped galvanizing include: (1) lower processing temperatures, (2) precise coating weight control, and (3) brighter, more uniform coatings which are easier to convert to Class A exposed quality painted surfaces.

The majority of electrogalvanizing lines can apply only pure (free) zinc coatings, known as EG for electrogalvanized steel. Selected lines can apply different types of coatings, like EGA (electro-galvanneal) or Zn-Ni (zinc-nickel).

There are no concerns about different alloy phases in the coating as with galvanneal coatings. The lack of aluminum in the coating results in improved weldability. The biggest concern with electrogalvanizing lines is the coefficient of friction. Electrogalvanized (EG) coatings have a relatively high coefficient of friction – higher than hot dipped galvanized coatings, but lower than galvanneal coatings. To improve formability of electrogalvanized sheets, some automakers choose to use a steel mill-applied pre-lube rather than a simple mill-applied rust preventive oil.

A representative EG line is shown in Figure 3. Different EG lines may use different technologies to apply the zinc crystals. Because the zinc crystals are deposited in a different fashion, these different processes may potentially result in different surface morphology and, in turn, a different coefficient of friction. Dry conditions may result in a higher coefficient of friction, but the “stacked plate-like surface morphology” (Figure 4) allows these coatings to trap and hold lubrication better than the smoother surfaces of hot dipped galvanizing coatings. Auto manufacturers should therefore consult the steel supplier for specific lubricant recommendations based on the forming needs.

Figure 3: Schematic of an electrogalvanizing line.

Figure 4: High magnification photograph of electrogalvanized steel surface showing stacked plate-like structure.

Zinc-Magnesium (ZM) Coatings

Galvanized coatings offer excellent corrosion protection to the underlying steel. Each type of galvanized coating has characteristics that make it suitable for specific applications and environments. The method by which the galvanization occurs (electrolytically applied vs. hot dipping) changes these characteristics, as does the coating chemistry (pure zinc vs. zinc alloy)

Adding small amounts of magnesium and aluminum affects the coating properties, which influences friction, surface appearance, and corrosion among other parameters.

Industries like agriculture and construction have used a coating known as ZAM for several decades. ZAM (Zinc-Aluminum-Magnesium) is primarily zinc, with approximately 6% Al and 3% Mg. However, the high aluminum content does not lend itself to a continuous galvanizing operation due to increased dross formation. The coating aluminum also degrades weldability.

A different coating, known as ZM, was commercialized around 2010. This zinc-rich coating typically has 1% to 3% of both magnesium and aluminum, with some companies using a slightly higher amount of aluminum. ZM coatings are typically applied using a hot dip approach like GI and GA, but with an appropriate bath chemistry. Exposed quality surfaces are achievable.

Even though ZM is a relatively hard coating, it is associated with lower friction and lower risk of galling and powdering than other common zinc coatings. This allows for parts to be successfully formed using higher blank holder forces, resulting in a wider BHF range between wrinkles and splits.Z-6

ZM coatings have similar joining characteristics and similar performance after phosphating / painting as hot dip galvanized coatings.

Enhanced cut edge corrosion protection relative to EG, GI, and GA coatings occurs due to the formation of a stable passivation layer on the bare steel edge that would be otherwise exposed to the environment. ZM coating corrosion dynamics are such that similar performance to EG, GI, and GA can be achieved at lower ZM coating weights.

Powdering resistance of ZM coatings are similar to that for GI and EG, and better than what is seen on GA coatings. ZM coatings have superior cyclic, perforating, and stone chip corrosion resistance.

Potential areas of application applications include:

- Hem flanges of doors, deck lids, and hoods

- Cut edges in inner hood, door, and deck lid panels

- Stone chip sensitive parts like hoods, fenders, doors, and body sides.

- Difficult to form parts that can benefit from the lower friction

Resistance Spot Welding

One of the methods by which the coatings are applied to the steel sheet surface is through a process called Hot Dipped Galvanizing (HDG). In this process, continuous coils of steel sheet are pulled at a controlled speed through a bath containing molten Zinc (Zn) at ~ 460° C. The Zn reacts with the steel and forms a bond. The excess liquid metal sticking on the sheet surface as it exits the bath is wiped off using a gas wiping process to achieve a controlled coating weight or thickness per unit area.

As mentioned earlier, AHSS are commercially available with Hot Dipped Galvannealed (HDGA) or Hot Dipped Galvanized (HDGI) coatings. The term “galvanize” comes from the galvanic protection that Zn provides to steel substrate when exposed to a corroding medium. An HDGA coating is obtained by additional heating of the Zn-coated steel at 450-590°C (840-1100°F) immediately after the steel exits the molten Zn bath. This additional heating allows iron (Fe) from the substrate to diffuse into the coating. Due to the diffusion of Fe and alloying with Zn, the final coating contains about 90% Zn and 10% Fe. Due to the alloying of Zn in the coating with diffused Fe, there is no free Zn present in the GA coating.

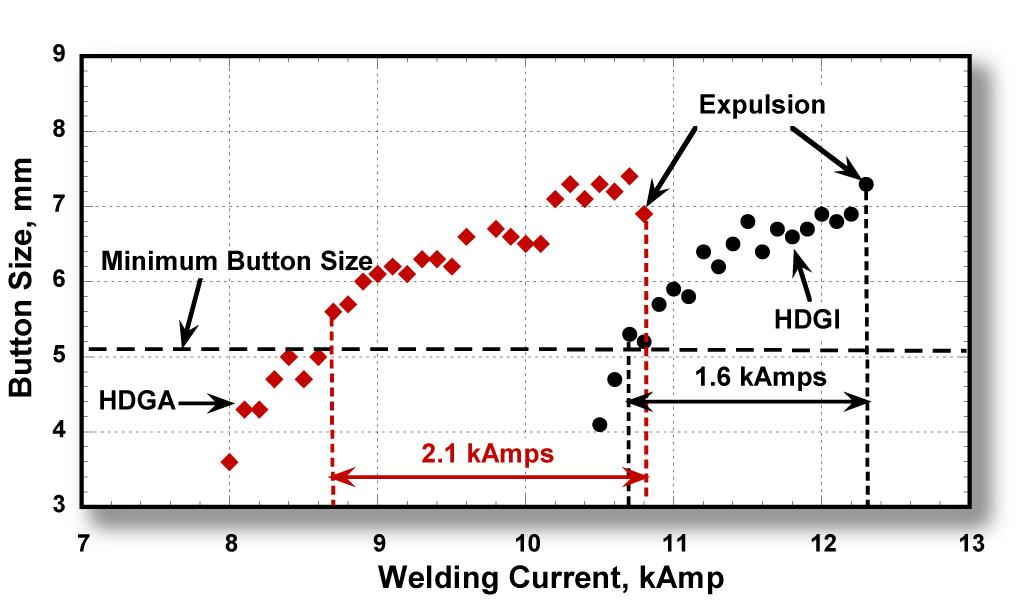

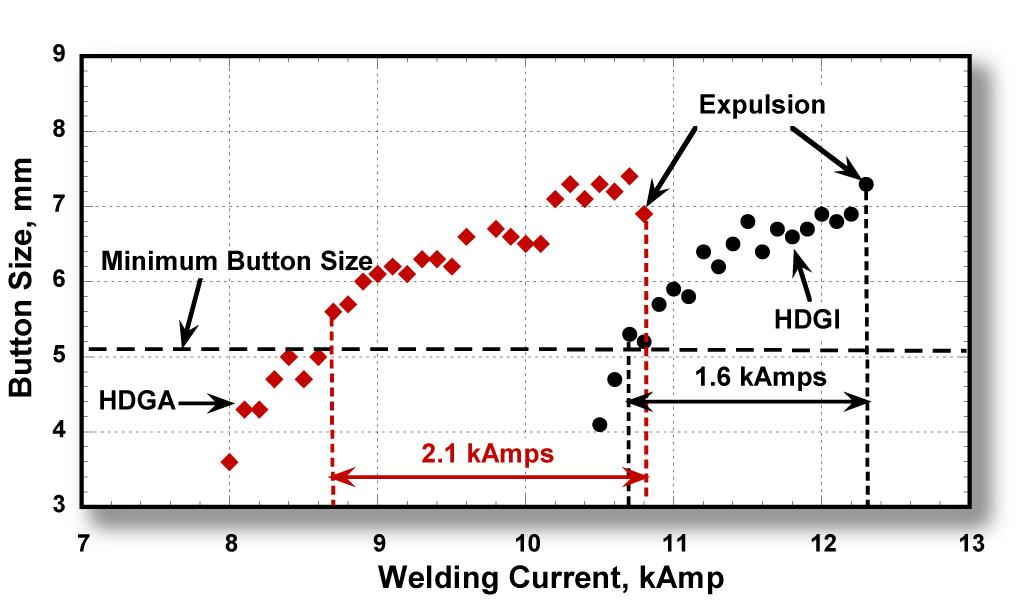

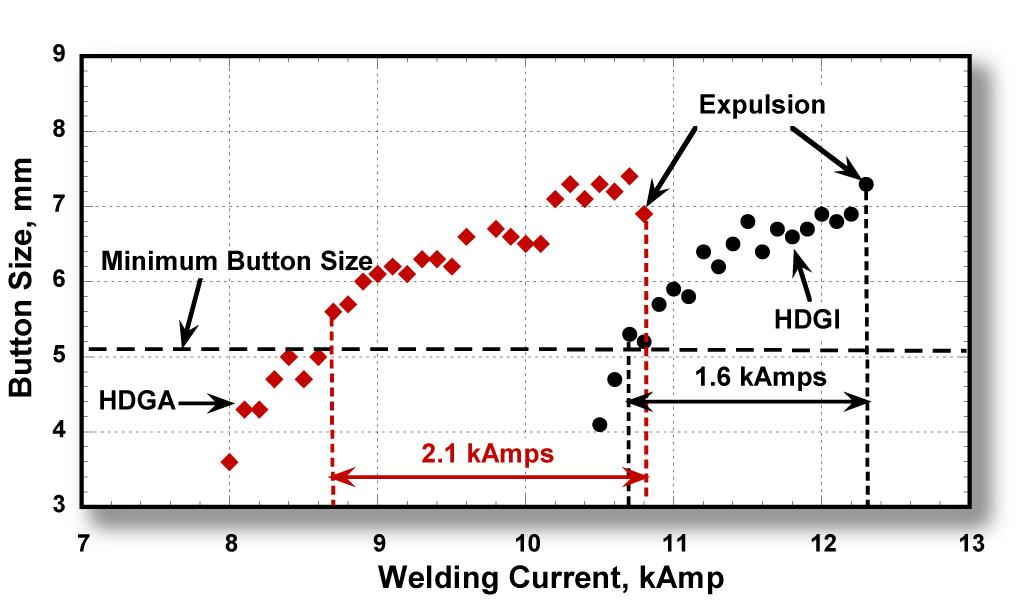

A studyT-7 was undertaken to examine whether differences exist in the RSW behavior of DP 420/800 with a HDGA coating compared to a HDGI coating. The Resistance SW evaluations consisted of determining the welding current ranges for the steels with HDGA and HDGI coatings. Shear and cross-tension tests also were performed on spot welds made on steels with both HDGA and HDGI coatings. Weld cross sections from both types of coatings were examined for weld quality. Weld micro hardness profiles provided hardness variations across the welds. Cross sections of HDGA and HDGI coatings, as well as the electrode tips after welding, were examined using a Scanning Electron Microscope (SEM). Composition profiles across the coating depths were analyzed using a glow-discharge optical emission spectrometer to understand the role of coating in RSW. Contact resistance was measured to examine its contribution to the current required for welding. The results indicated that DP 420/800 showed similar overall welding behavior with HDGA and HDGI coatings. One difference noted between the two coatings was that HDGA required lower welding current to form the minimum nugget size. This may not be an advantage in the industry given the current practice of frequent electrode tip dressing. Welding current range for HDGA was wider than for HDGI. However, the welding current range of 1.6 kA obtained for HDGI coated steel compared to 2.2 kA obtained for the HDGA coated steel is considered sufficiently wide for automotive applications and should not be an issue for consideration of its use (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Welding current ranges for 1.6-mm DP 420/800 with HDGA and HDGI coatings.T-7

As was mentioned briefly in Resistance Spot Welding, electrode wear is a larger issue when welding coated steels. In high-volume automotive production of Zn-coated steels, the rate of electrode wear tends to accelerate compared to the rate when welding uncoated steels. The accelerated electrode wear with coated steel is attributable to two mechanisms. The first mechanism is increasing in the electrode contact area (sometimes referred to as mushrooming effect) that results in decreased current density and smaller weld size. The second mechanism is electrode face erosion/pitting due to chemical interaction of the Zn coating with the Cu alloy electrode, forming various brass layers. These layers tend to break down and extrude out to the edges of the electrode (Figure 2). To overcome this electrode wear issue, the automotive industry is using automated electrode dressing tools and/or weld schedule adjustments via the weld controller. Typical adjustments include increase in welding current and/or increase in electrode force, while producing more welds. Research and development work has been conducted to investigate alternative electrode material and geometries for improving electrode life.

Figure 2: Erosion/pitting and extrusion of brass layers on worn RSW electrode.U-2

The resistance weldability of coated steels can also cause problems. In many applications, more intricate welding schedules are used to ensure welds meet the size and strength requirements. Studies have been conducted to determine the nugget growth and formation mechanisms to properly select parameters for each pulse of a three-pulse welding scheduleJ-2 (Figure 3). The first pulse, high current and short weld time, is used to mitigate the effects of the coating on welding and develop contact area at the sheet-to-sheet interface. The second pulse, low current long weld time, is used to grow the weld nugget and minimize internal defects. The third pulse, medium current and long weld time, is used to grow the weldability current range and maximize the nugget diameter.

Figure 3: Weld growth mechanism of optimized three-pulse welding condition.J-2