![Cutting, Blanking, Shearing & Trimming]()

Cutting, Cutting-Blanking-Shearing-Trimming

Advanced High-Strength Steels (AHSS) exhibit high degrees of work hardening, resulting in improved forming capabilities compared to conventional HSLA steels. However, the same high work hardening creates higher strength and hardness in sheared or punched edges, leading to reduced edge ductility. Microstructural features in some AHSS grades contribute to their sheared edge performance. While laser cutting results in less edge damage than mechanical cutting methods, the heat from laser cutting produces a localized hear treatment, changing the strength and hardness at the edge. Achieving the best formability for chosen processing path requires generating a consistent good quality edge from the cutting operation.

To avoid unexpected problems during a program launch, use production intent tooling as early in the development as possible. This may be a challenge since blanking dies are usually among the last set of tools completed. In the interim, many companies choose to use laser cut blanks. Tool, blank, and process development must account for the lower-ductility sheared edges in production blanks.

Edge Ductility Measurements

This article describes the impact of cutting and cut-edge quality on edge ductility. The primary tests which quantify edge ductility are Hole Expansion Testing, 2-D Edge Tension Testing, and Half Specimen Dome Testing. These links detail the testing procedures. The Hole Expansion Testing article has additional information pertaining to the effect of burr orientation and punch shape.

Cut Edge Quality

Any mechanical cutting operation such as blanking, piercing, shearing, slitting, or trimming reduces edge ductility. Each of these processes generate a zone of high work hardening and a reduced n-value. This work hardened zone can extend one-half metal thickness from the cut edge. This is one reason why edges fail at strains lower than that predicted by the forming limit curve for that particular grade (Note that FLCs were developed based on necking failure, and that edge cracking is a different failure mechanism).

DP and TRIP steels have islands of martensite located throughout the ferritic microstructure, including at the cut edges. These hard particles act as crack initiators and further reduce the allowable edge stretch. Metallurgical changes to the alloy minimize the hardness differences between the phases, resulting in improved edge ductility. Laser, EDM or water jet cutting approaches minimize work hardening at the edges and the associated n-value reduction, also leading to improved edge ductility.

Putting shear angles into cutting tools is a well-known approach to reduce cutting forces. Modifying the cutting tool leads to other benefits in terms of edge ductility. Researchers studied the effects of a beveled punch instead of the traditional flat bottom punch.S-9, S-50, S-52 In these studies, the optimized bevel angle was between 3 and 6 degrees, the shear direction was parallel the rolling direction of the coil with a die clearance of 17%. With the optimal cutting parameters, the hole expansion ratio increased by 60% when compared to conventional flat punching process. As expected, a reduction in the maximum shearing force occurred – by more than 50% in certain conditions. Dropping the shearing force helps reduce the snap through reverse tonnage, leading to longer tool and press life.

Multiple studies examine the trimmed edge quality based on various cutting conditions in mechanical shearing operations and other methods to produce a free edge such as milling and cutting using a laser or water jet. Edge quality varies based on parameters like cutting clearances, shear angles, and rake angles on mechanical shearing operations.

A typical mechanically sheared steel edge has 4 main zones – rollover, burnish, fracture, and burr, as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Cross Section of a Punched Hole Showing the Shear Face Components and Shear Affected Zone.K-10

Parts stamped from conventional mild and HSLA steels have historically relied on burr height as the main measure of edge quality, where the typical practice targeted a burr height below 10% of metal thickness and slightly larger for thicker steel. Finding a burr exceeded this threshold usually led to sharpening or replacing the trim steels, or less likely, adjusting the clearances to minimize the burr.

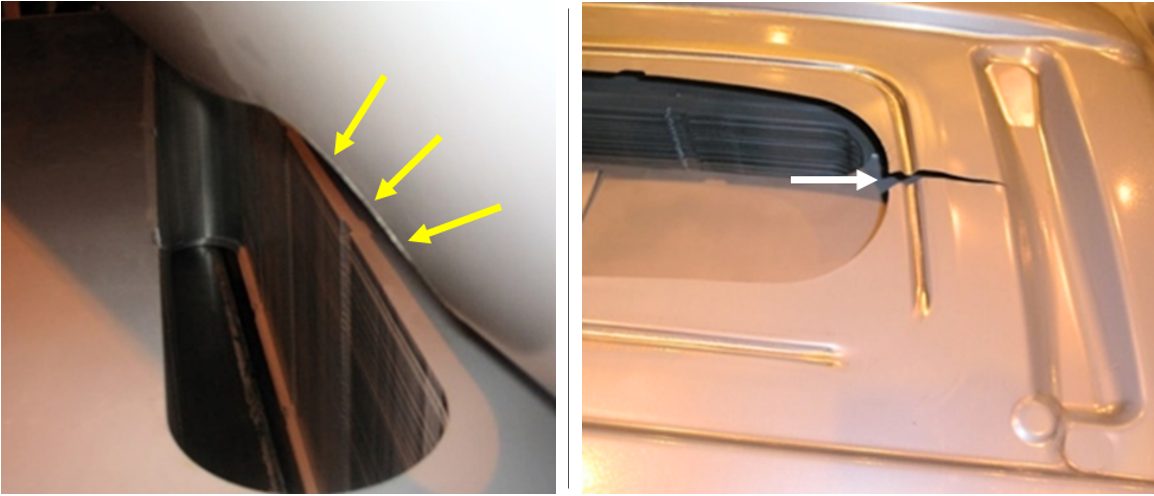

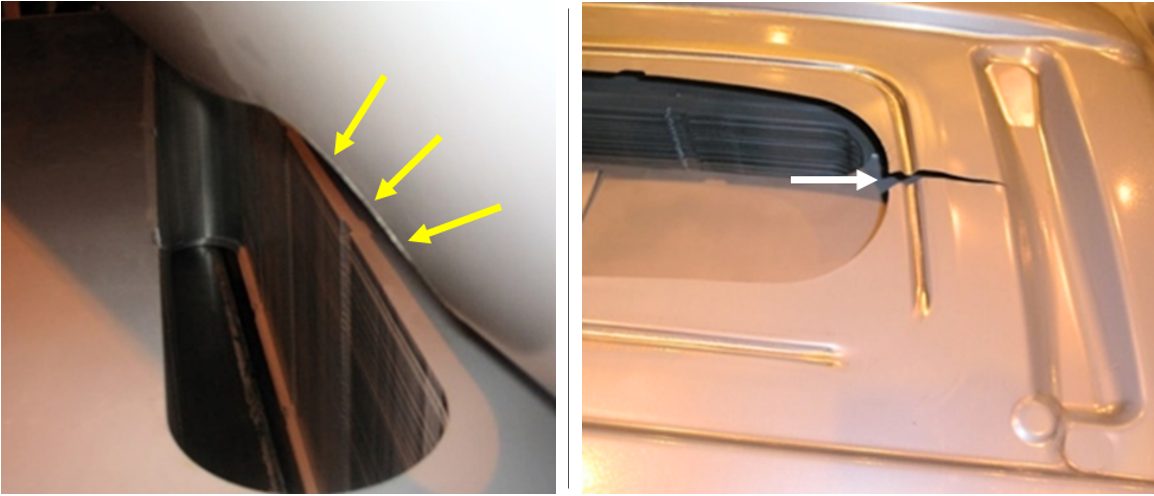

Greater burr height is associated with additional cold working and creates stress risers that can lead to edge splitting. These splits, however, are global formability related failures where the steel thins significantly at and around the split, independent of the local formability edge fractures associated with AHSS. A real-world example is shown in Figure 2, which presents a conventional BH210 steel grade liftgate with an excessive burr in the blank that led to global formability edge splitting in the draw die. The left image in Figure 2 highlights the burr on the underside of the top blank, with the remainder of the lift below it. The areas next to the split in the right image of Figure 2 shows the characteristic thinning associated with global formability failures.

Figure 2: Excessive burr on the blank led to a global formability split on the formed liftgate. The root cause was determined to be dull trim steels resulting in excessive work hardening.U-6

Due to their progressively higher yield and tensile strengths, AHSS grades experience less rollover and smaller burrs. They tend to fracture with little rollover or burr. As such, detailed examination of the actual edge condition under various cutting conditions becomes more significant with AHSS as opposed characterizing edge quality by burr height alone. Examination of sheared edges produced under various trimming conditions, including microhardness testing to evaluate work hardening after cold working the sheared edge, provides insight on methods to improve cut edge formability. The ideal condition to combat local formability edge fractures for AHSS was to have a clearly defined burnish zone with a uniform transition to the fracture zone. The fracture zone should also be smooth with no voids, secondary shear or edge damage (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Ideal sheared edge with a distinct burnish zone and a smooth fracture zone (left) and a cross section of the same edge (right).U-6

If clearances are too small, secondary shear can occur and the potential for voids due to the multiphase microstructure increases, as indicated in Figure 4. Clearances that are too large create additional problems that include excessive burrs and voids. A nonuniform transition from the burnish zone to the fracture zone is also undesirable. These non-ideal conditions create propagation sites for edge fractures.

Figure 4: Sheared edge with the trim steel clearance too small (left) and a cross section of the same edge (right) showing a micro crack on the edge. Tight clearance leading to secondary shear increases likelihood of edge fracture.U-6

There are multiple causes for a poor sheared edge condition, including but not limited to:

- the die clearance being too large or too small,

- a cutting angle that is too small,

- worn, chipped, or damaged tooling,

- improperly ground or sharpened tooling,

- improper die material,

- improperly heat-treated die material,

- improper (or non-existent) coating on the tooling,

- misaligned die sections,

- worn wear plates, and

- out of level presses or slitting equipment.

The higher loads required to shear AHSS with increasingly higher tensile strength creates additional deflection of dies and processing equipment. This deflection may alter clearances measured under a static condition once the die, press, or slitting equipment is placed under load. As a large percentage of presses, levelers, straighteners, blankers, and slitting equipment were designed years ago, the significantly higher loads required to process today’s AHSS may exceed equipment beyond their design limits, dramatically altering their performance.

A rocker panel formed from DP980 provides a good example showing the influence of cut edge quality. A master coil was slit into several narrower coils (mults) before being shipped to the stamper. Only a few mults experienced edge fractures, which all occurred along the slit edge. Understanding that edge condition is critical with respect to multiphase AHSS, the edge condition of the “good” mults and the “bad” mults were examined under magnification. The slit edge from a problem-free lift (Figure 5) has a uniform burnish zone with a uniform transition to the smooth fracture zone. This is in contrast with Figure 6, from the slit edge from a different mult of the same coil in which every blank fractured at the slit edge during forming. This edge exhibits secondary shear as well as a thick burnish zone with a non-uniform transition from the burnish zone to the fracture zone.

Figure 5: Slit edges on a lift of blanks that successfully produced DP980 rocker panels. Note the uniform transition from the burnish zone to the fracture zone with a smooth fracture zone as well.U-6

Figure 6: Slit edges on a lift of blanks from the same master coil that experienced edge fractures during forming. Note the obvious secondary shear as well as the thicker, nonuniform transition from the burnish to the fracture zone.U-6

Cutting Clearances: Burr Height and Tool Wear

Cutting and punching clearances should be increased with increasing sheet material strength. The clearances range from about 6% of the sheet material thickness for mild steel up to 16% or even higher as the sheet metal tensile strength exceeds 1400 MPa.

A study C-2 compared the tool wear and burr height formation associated with punching mild steel and several AHSS grades. In addition to 1.0 mm mild steel (140 MPa yield strength, 270 MPa tensile strength, 38% A80 elongation), AHSS grades tested were 1.0 mm samples of DP 350Y600T (A80=20%), DP 500Y800T (A80=8%), and MS 1150Y1400T (A80 = 3%). Tests of mild steel used a 6% clearance and W.Nr. 1.2363 / AISI A2 tool steel hardened to 61 HRC. The AHSS tests used engineered tool steels made from powder metallurgy hardened to 60-62 HRC. The DP 350/600 tests were run with a TiC CVD coating, and a 6% clearance. Tool clearances were 10% for the MS 1150Y1400T grade and 14% for DP 500Y800T.

In the Tool Wear comparison, the cross-section of the worn punch was measured after 200,000 hits. Punches used with mild steel lost about 2000 μm2 after 200,000 hits, and is shown in Figure 7 normalized to 1. The relative tool wear of the other AHSS grades are also shown, indicating that using surface treated high quality tool steels results in the same level of wear associated with mild steels punched with conventional tools.

Figure 7: Tool wear associated with punching up to DP 500Y800T using surface treated high quality tool steels is comparable to mild steel punched with conventional tools.C-2

Figure 8 shows the burr height test results, which compared burr height from tests using mild steel punched with conventional tool steel and two AHSS grades (DP 500Y800T and MS 1150Y1400T) punched with a PM tool steel. The measured burr height from all AHSS and clearance combinations evaluated were sufficiently similar that they are shown as a single curve.

Figure 8: Burr height comparison for mild steel and two AHSS grades as a function of the number of hits. Results for DP 500Y800T and Mart 1150Y1400T are identical and shown as the AHSS curve.C-2

Testing of mild steel resulted in the expected performance where burr height increases continuously with tool wear and clearance, making burr height a reasonable indicator of when to sharpen punching or cutting tools. However, for the AHSS grades studied, burr height did not increase with more hits. It is possible that the relatively lower ductility AHSS grades are not capable of reaching greater burr height due to fracturing, where the more formable mild steel continues to generate ever-increasing burr height with more hits and increasing tool wear.

Punching AHSS grades may require a higher-grade tool steel, possibly with a surface treatment, to avoid tool wear, but tool regrinding because of burrs may be less of a problem. With AHSS, engineered tool steels may provide longer intervals between sharpening, but increasing burr height alone should not be the only criterion to initiate sharpening: cut edge quality as shown in the above figures appears to be a better indicator. Note that regrinding a surface treated tool steel removes the surface treatment. Be sure to re-treat the tool to achieve targeted performance.

Cutting Clearances: General Recommendations

Depending on the source, the recommended die clearance when shearing mild steels is 5% to 10% of metal thickness. For punched holes, these represent per-side values. Although this may have been satisfactory for mild steels, the clearance should increase as the tensile strength of the sheet metal increases.

The choice of clearance impacts other aspects of the cutting process. Small cutting clearances require improved press and die alignment, greater punching forces, and cause greater punch wear from abrasion. As clearance increases, tool wear decreases, but rollover on the cut edge face increases, which in the extreme may lead to a tensile fracture in the rollover zone (Figure 9). Also, a large die clearance when punching high strength materials with a small difference in yield and tensile strength (like martensitic grades) may generate high bending stresses on the punch edge, which increases the risk of chipping.

Figure 9: Large rollover may lead to tensile fracture in the rollover zone.

Figure 10 compares cut edge appearance after punching a martensitic steel with 1400 MPa tensile strength using either 6% or 14% clearance. The larger clearance is associated with greater rollover, but a cleaner cut face.

Figure 10: Cut edge appearance after punching CR 1400T-MS with 6% (left) and 14% (right) die clearance. The bottom images show the edge appearance for the full sheet thickness, Note using 6% clearance resulted in minimal rollover, but uneven burnish and fracture surfaces. In contrast, 14% clearance led to noticeable rollover, but a clean burnish and fracture surface.T-20

A comparison of the edges of a 2 mm thick complex phase steel with 700 MPa minimum tensile strength produced under different cutting conditions is presented in Figure 11. The left image suggests that either the cutting clearance and/or the shearing angle was too large. The right image shows an optimal edge likely to result in good edge ductility.

Figure 11: Cut edge appearance of 2 mm HR 700Y-MC, a complex phase steel. The edge on the right is more likely to result in good edge ductility.T-20

The recommended clearance is a function of the sheet grade, thickness, and tensile strength. Figures 12 to 15 represent general recommendations from several sources.

Figure 12: Recommended Clearance as a Function of Grade and Sheet Thickness.T-23

Figure 13: Recommended Cutting Clearance for Punching.D-15

Figure 14: Recommended die clearance for blanking/punching advanced high strength steel.T-20

Figure 15: Multiply the clearance on the left with the scaling factor in the right to reach the recommended die clearance.D-16

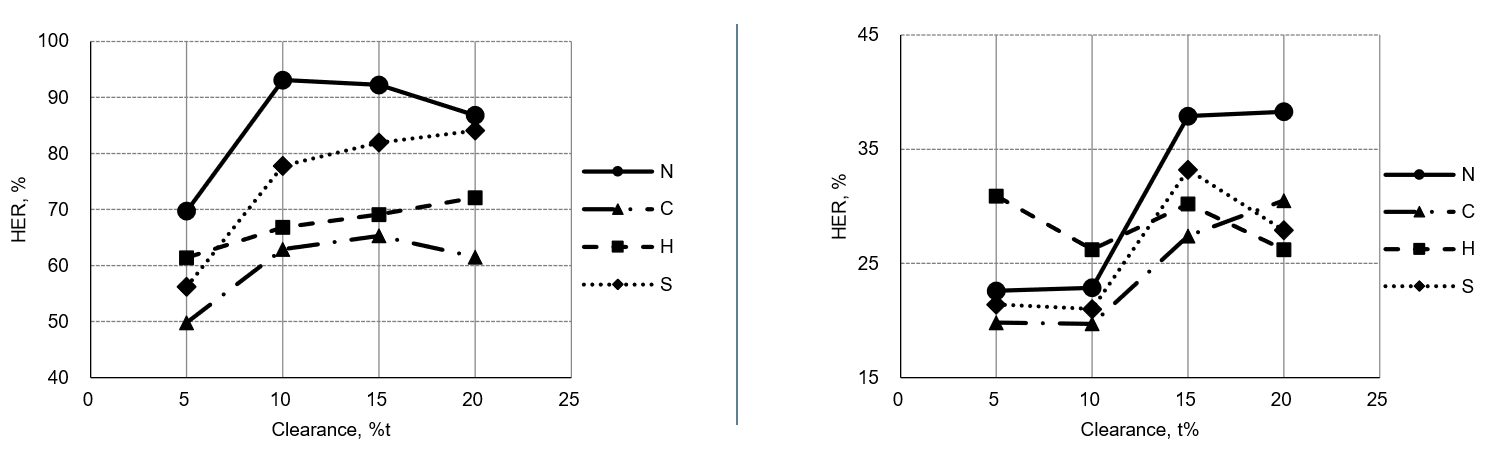

Figure 16 highlights the effect of cutting clearance on CP1200, and reinforces that the historical rule-of-thumb guidance of 10% clearance does not apply for all grades. In this studyU-3, increasing the clearance from 10% to 15% led to a significant improvement in hole expansion. The HER resulting from a 20% clearance was substantially better than that from a 10% clearance, but not as good as achieved with a 15% clearance. These differences will not be captured when testing only to the requirements of ISO 16630, which specifies the use of 12% clearance.

Figure 16: Effect of hole punching clearance on hole expansion of Complex Phase steel grade CP1200.U-3

Cutting speed influences the cut edge quality, so it also influences the optimal clearance for a given grade. In a study published in 2020G-49, higher speeds resulted in better sheared edge ductility for all parameters evaluated, with those edges having minimal rollover height, smoother sheared surface and negligible burr. Two grades were evaluated: a dual phase steel with 780MPa minimum tensile strength and a 3rd Generation steel with 980 MPa minimum tensile strength.

Metallurgical characteristics of the sheet steel grade also affects hole expansion capabilities. Figure 17 compares the HER of DP780 from six global suppliers. Of course, the machined edge shows the highest HER due to the minimally work-hardened edge. Holes formed with 13% clearance produced greater hole expansion ratios than those formed with 20% clearance, but the magnitude of the improvement was not consistent between the different suppliers.K-56

Figure 17: Cutting clearance affects hole expansion performance in DP780 from six global suppliers.K-56

Punch Face Design

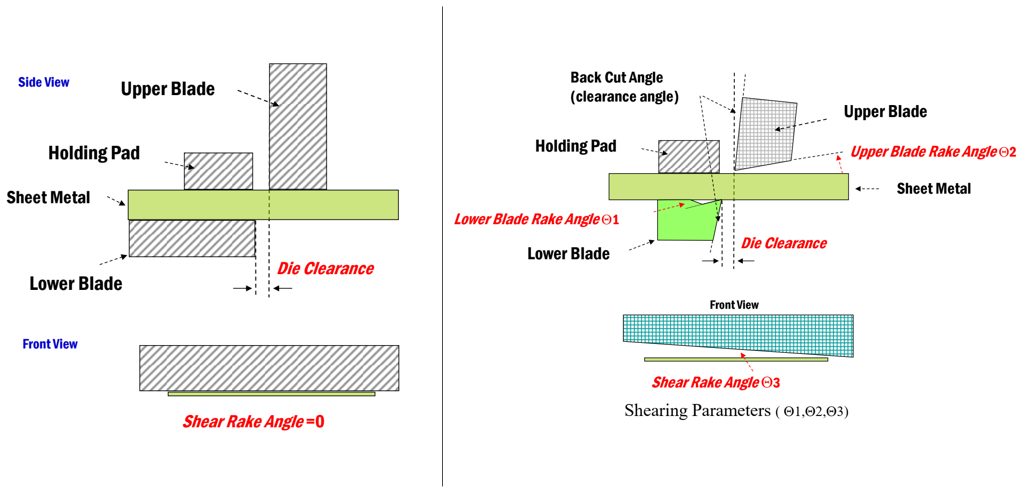

Practitioners in the field typically do not cut perpendicular to the sheet surface – angled punches and blades are known to reduce cutting forces. For example, long shear blades might have a 2 to 3 degree angle on them to minimize peak tonnages. There are additional benefits to altering the punch profile and impacting angle.

Snap-though or reverse tonnage results in stresses which may damage tooling, dies, and presses. Tools may crack from fatigue. Perhaps counter to conventional thinking, use of a coated punch increases blanking and punching forces. The coating leads to lower friction between the punch and the sheet surface, which makes crack initiation more difficult without using higher forces.

Unlike a coated tool, a chamfered punch surface reduces blanking and punching forces. Figure 18 compares the forces to punch a 5 mm diameter hole in 1 mm thick MS-1400T using different punch shapes. A chamfered punch was the most effective in reducing both the punching force requirements and the snap-through tonnage (the shock waves and negative tonnage readings in Figure 18). The chamfer should be large enough to initiate the cut before the entire punch face is in contact with the sheet surface. A larger chamfer increases the risk of plastic deformation of the punch tip.T-20

Figure 18: A chamfered punch reduces peak loads and snap-through tonnage.K-15

A different study P-16 showed more dramatic benefits. Use of a rooftop punch resulted in up to an 80% reduction in punching force requirements compared with a flat punch, with a significant reduction in snap-through tonnage. Cutting clearance had only minimal effect on the results. (Figure 19)

Figure 19: A rooftop-shaped punch leads to dramatic reductions in punch load requirements and snap-through tonnage.P-16

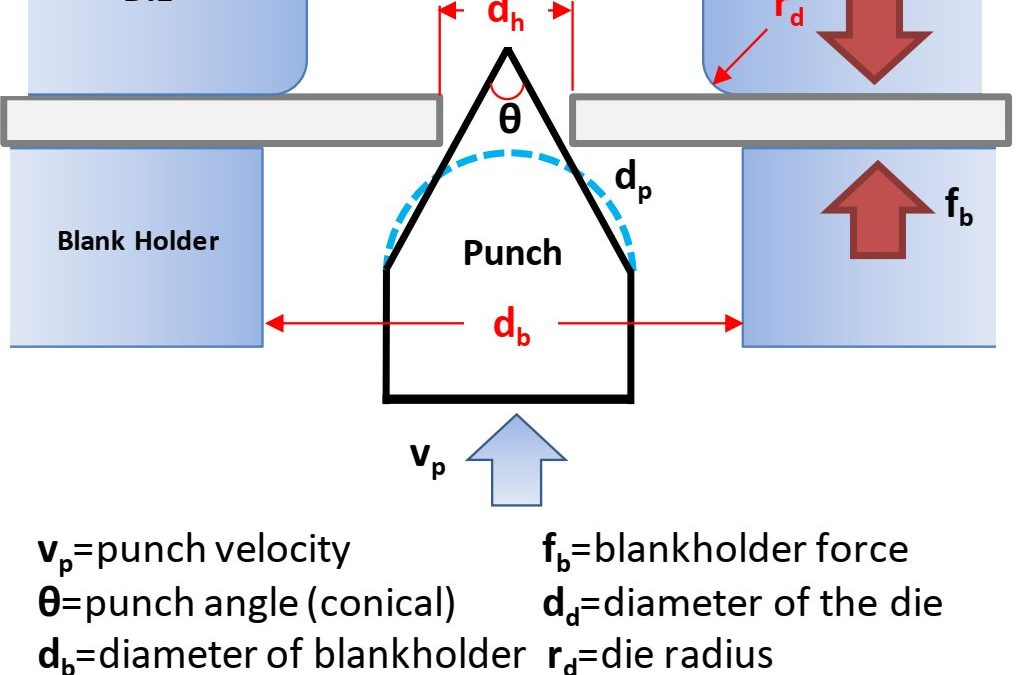

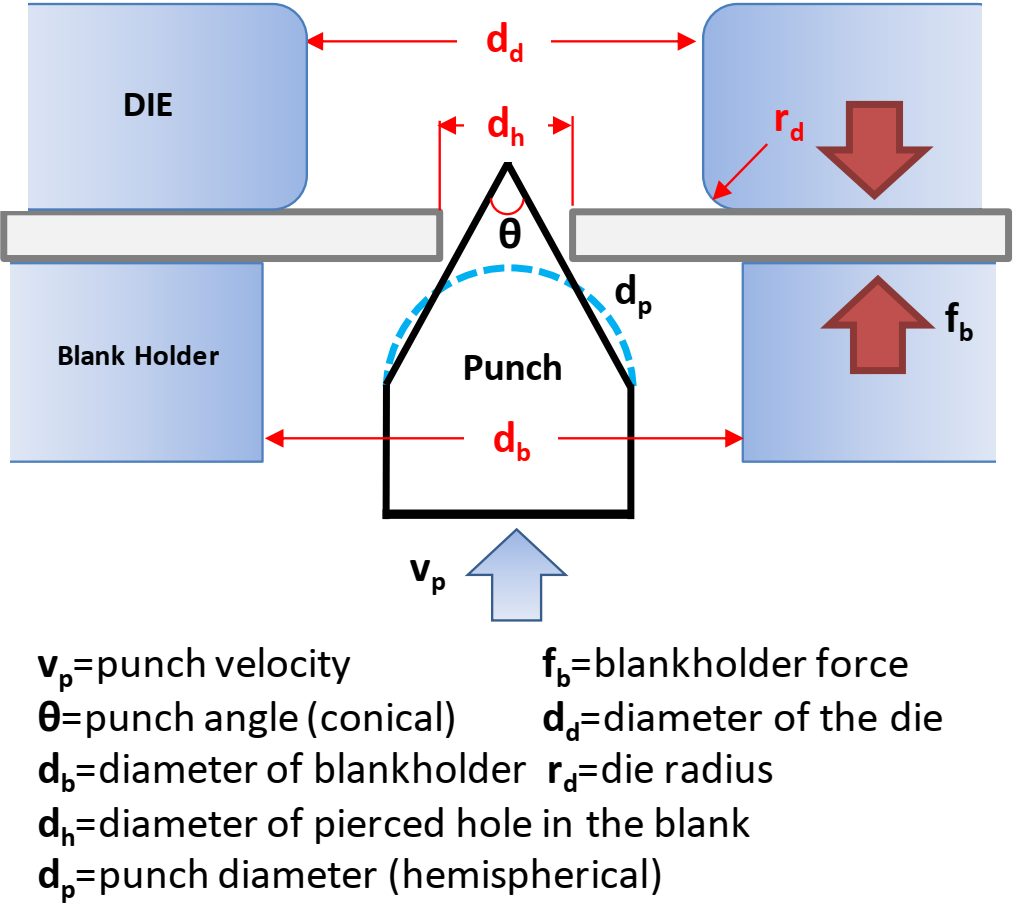

Use of a beveled punch (Figure 20) provides similar benefits. A study S-52 comparing DP 500/780 and DP 550/980 showed a reduction in the maximum piercing force of more than 50% with the use of a beveling angle between 3 and 6 degrees. The shearing force depends also upon the die clearance during punching, with the optimum performance seen with 17% die clearance. The optimal punching condition results in more than 60% improvement in the hole expansion ratio when compared to conventional flat head punching process. The optimal bevel cut edge in Figure 21 shows a uniform burnish zone with a uniform transition to the smooth fracture zone – the known conditions to produce a high-ductility edge.

Figure 20: Schematic showing a beveled punch.S-52

Figure 21: A bevel cut edge showing uniform burnish zone with a uniform transition to the smooth fracture zone.S-52

Effect of Edge Preparation Method on Ductility

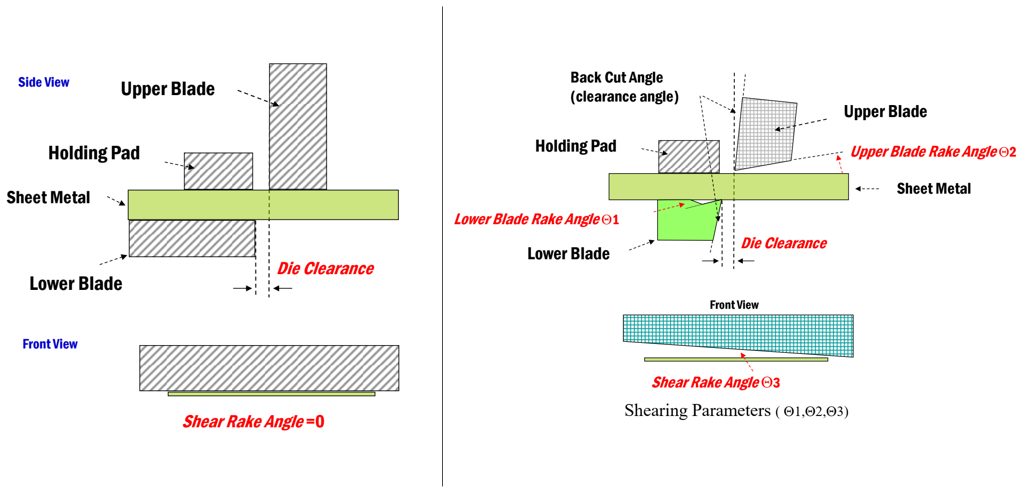

A flat trim condition where the upper blade and lower blade motions are parallel and there is no shear rake angle is known to produce a trimmed edge with limited edge stretchability (Figure 22, left image). In addition to split parts, tooling damage and unexpected down time results. Metal stampers have known that shearing with a rake angle Figure 22, right image) will reduce cutting forces compared with using a flat cut. With advanced high strength steels, there is an accompanying reduction in forming energy requirements of up to 20% depending on the conditions, which represents a tremendous drop in snap-through or reverse tonnage. Figure 22 visually describes the upper and lower blade rake angles and the shear rake angle.

Figure 22: Flat trim (left) and shear trim (right) conditions showing rake angle definitions.S-53

Researchers have also found that it is possible to increase sheared edge ductility with optimized rake angles. Citation S-53 used 2-D Edge Tension Testing and the Half-Specimen Dome Test to qualify the effects of these rake angles, and determine the optimum settings. After preparing the trimmed edge with the targeted conditions, the samples were pulled in a tensile test or deformed using a hemispherical punch. The effect of the trimming conditions was seen in the measured elongation values and the strain at failure, respectively. The results are summarized in Figures 23-25. Some of the tests also evaluated milled, laser trimmed, and water jet cut samples. Shear Trim 1, 2, and 3 refer to the shear trim angle in degrees. The optimized shear condition also includes a 6-degree rake angle on both the upper and lower blades, as defined in Figure 22.

Conclusions from this study include:

- Mechanically shearing the edge cold works the steel and reduces the work hardening exponent (n-value), leading to less edge stretchability.

- Samples prepared with processes that avoided cold working the edges, like laser or water jet cutting outperformed mechanically sheared edges.

- Optimizing the trim shear conditions or polishing a flat trimmed edge approaches what can be achieved with laser trimming and water jet cutting.

- Shearing parameters such as clearance, shear angle and rake angle also play a large part in improving edge stretch.

Figure 23: Effect of edge preparation on stretchability as determined using a tensile test for DP 350Y600T (left) and DP 550Y980T (right).S-53

Figure 24: Effect of edge preparation on stretchability as determined using a dome test for DP 350Y600T (left) and DP 550Y980T (right).S-53

Figure 25: Optimizing the trim shear conditions or polishing a flat trimmed edge approaches what is achievable with laser trimming and water jet cutting. Data from dome testing of DP 350Y/600T.S-53

The optimal edge will have no mechanical damage and no microstructural changes as you go further from the edge. Any process that changes the edge quality from the bulk material can influence performance. This includes the mechanical damage from shearing operations, which cold works the edge leading to a reduction in ductility. Laser cutting also changes the edge microstructure, since the associated heat input is sufficient to alter the engineered balance of phases which give AHSS grades their unique properties. However, the heat from laser cutting is sometimes advantageous, such as in the creation of locally softened zones to improve cut edge ductility in some applications of press hardening steels.

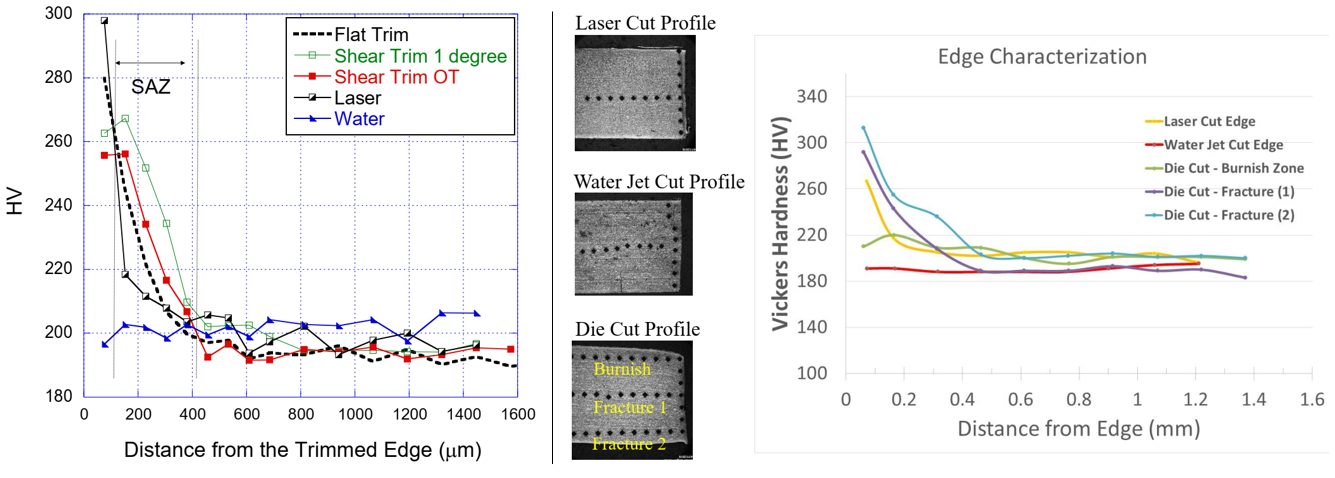

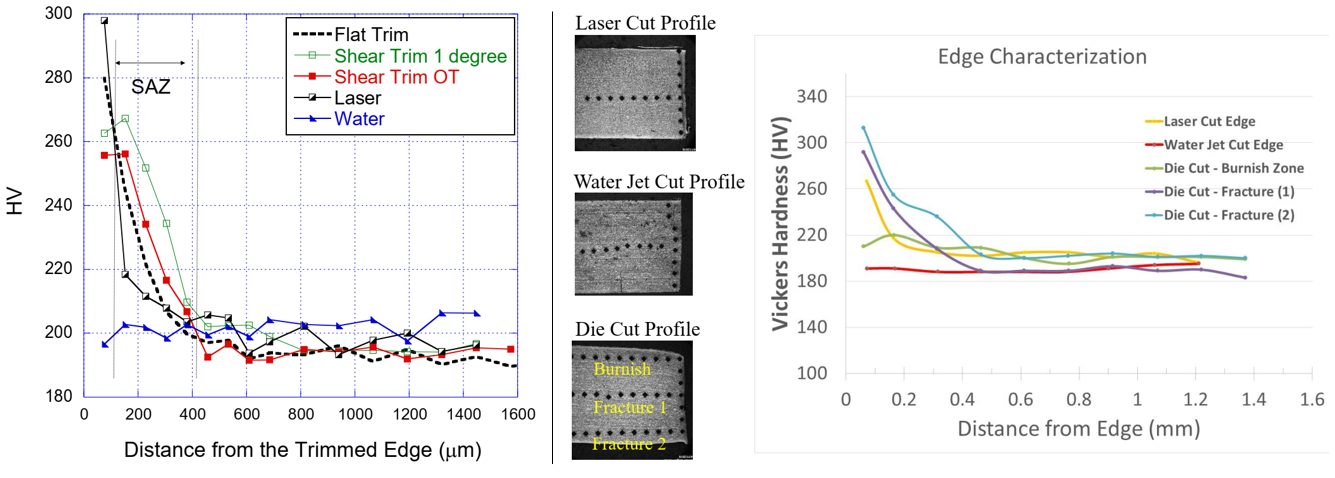

The effects of edge preparation on the shear affected zone is presented in Figure 26. A flatter profile of the Vickers microhardness reading measured from the as-produced edge into the material indicates the least work-hardening and mechanical damage resulting from the edge preparation method, and therefore should result in the greatest edge ductility. This is certainly the case for water jet cutting, where a flat hardness profile in Figure 26 correlates with the highest ductility measurements in Figures 22 to 25. Unfortunately, water jet cutting is not always practical, and introduces the risk of rust forming at the newly cut edge.

Figure 26: Microhardness profile starting at cut edge generated using different methods. Left image is from Citation S-53, and right image is from C-13.

Two-stage piercing is another method to reduce edge strain hardening effects. Here, a conventional piercing operation is followed by a shaving operation which removes the work-hardened material created in the first step, as illustrated in Figure 27.P-17 A related studyF-10 evaluated this method with a 4 mm thick complex phase steel with 800 MPa tensile strength. Using the configuration documented in this reference, single-stage shearing resulted in a hole expansion ratio of only 5%, where the addition of the shaving operation improved the hole expansion ratio to 40%.

Figure 27: Two-stage piercing improves cut edge ductility. Image adapted from Citation P-17.

Figure 28 highlights the benefits of two-stage pre-piercing for specific grades, showing a 2x to 4x improvement in hole expansion ratio for the grades presented.

Figure 28: Pre-piercing improves the hole expansion ratio of AHSS Grades.S-10

Key Points

- Clearances for punching, blanking, and shearing should increase as the strength of the material increases, but only up to a point. At the highest strengths, reducing clearance improves tool chipping risk.

- Lower punch/die clearances lead to accelerated tool wear. Higher punch/die clearances generate more rollover/burr.

- ISO 16630, the global specification for hole expansion testing, specifies the use of 12% punch-to-die clearance. Optimized clearance varies by grade, so additional testing may prove insightful.

- Recommended clearance as a percentage of sheet thickness increases with thickness, even at the same strength level.

- Burr height increases with tool wear and increasing die clearances for shearing mild steel, but AHSS tends to maintain a constant burr height. This means extended intervals between tool sharpening may be possible with AHSS parts, providing edge quality and edge performance remain acceptable.

- Edge preparation methods like milling, laser trimming, and water-jet cutting minimize cold working at the edges, resulting in the greatest edge ductility,

- Laser cut blanks used during early tool tryout may not represent normal blanking, shearing, and punching quality, resulting in edge ductility that will not occur in production. Using production-intent tooling as early as possible in the development stage minimizes this risk.

- Shear or bevel on punches and trim steel reduces punch forces, minimizes snap-through reverse tonnage, and improves edge ductility.

- Mild steel punched with conventional tools and AHSS grades punched with surface treated engineered PM tool steels experience comparable wear.

- Maintenance of key process variables, such as clearance and tool condition, is critical to achieving long-term edge stretchability.

- The optimal edge appearance shows a uniform burnish zone with a uniform transition to a smooth fracture zone.

Back To Top

Testing and Characterization

The term local formability describes when part and process design, in addition to sheet metal properties like strength and elongation, influence the amount of deformation the metal can undergo prior to failure. Cutting, punching or other methods of obtaining a trimmed blank or an internal hole results in cracks, rough edges, work-hardening and other edge damage – all of which influences edge quality. The challenges of capturing all of the factors that influence edge quality makes the prediction of fracture severity and cut edge expansion very difficult and usually impossible. The many variables highlight the need for a standardized test method. However, restricted sample preparation and testing variables in these standards do not reflect the variety of conditions encountered in production environments. Use caution when comparing results generated under different conditions.

Hole Expansion Testing

The Hole Expansion test (HET) quantifies the edge stretching capability of a sheet metal grade having a specific edge condition. Higher values of the hole expansion ratio are associated with grades and forming methods more likely to have improved local formability characteristics.

Steel producers study hole expansion capacity to create new products with targeted edge stretching performance through modifications of chemistry, rolling and thermal practices. Product designers use the hole expansion test to determine if the chosen steel grade has the inherent forming characteristics to meet their targeted shape with their chosen forming system. If they are not compatible, the chosen grade must change or aspects of the forming process must change, or possibly both.

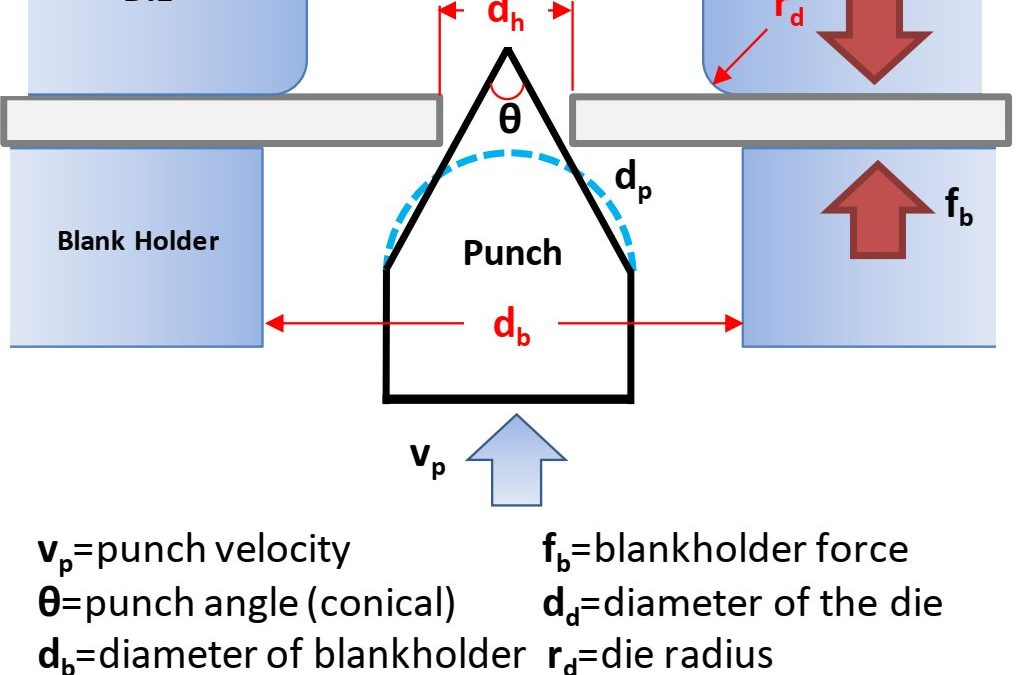

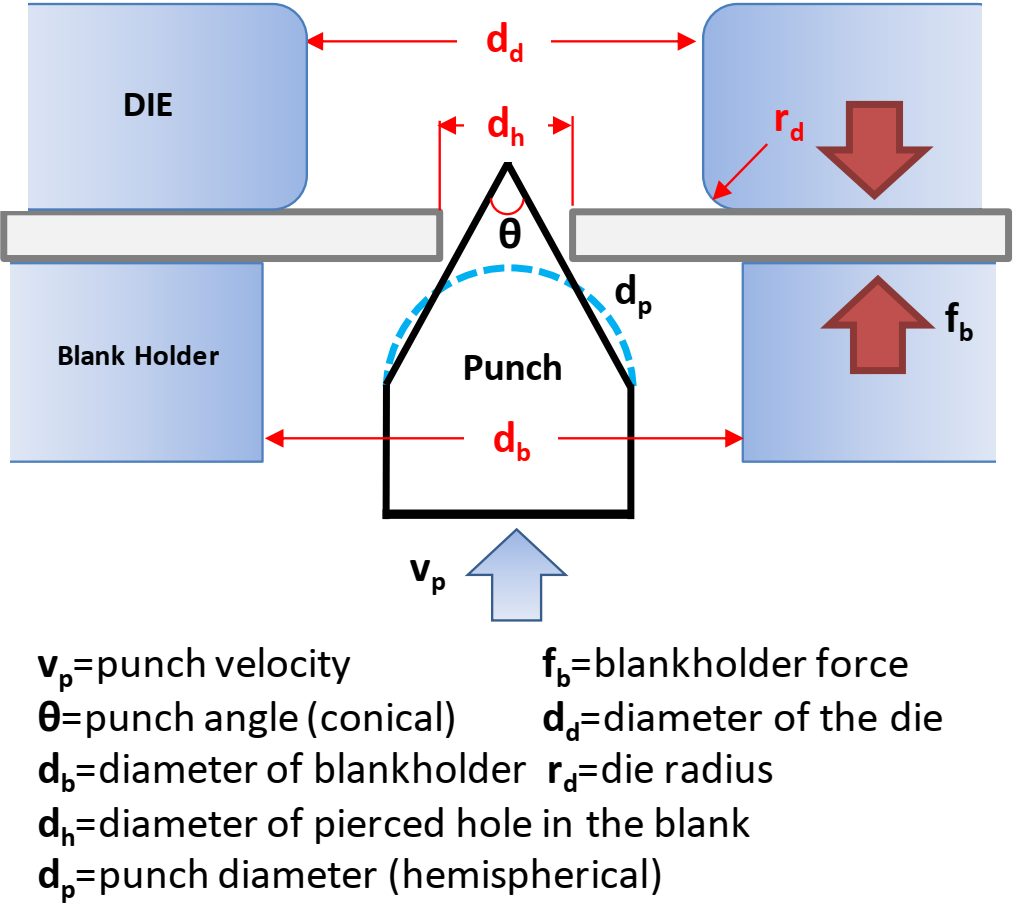

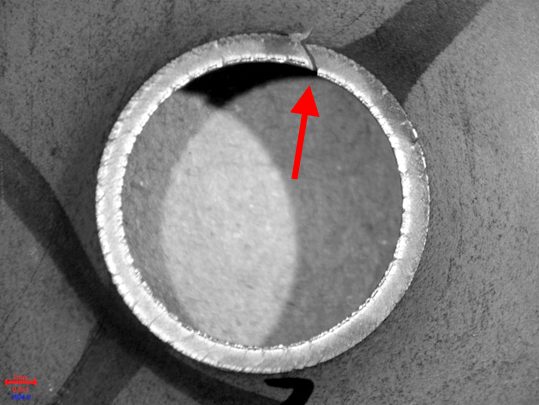

ISO 16630 is the primary standard used which describes the test method and constraints.I-9 Others, like JIS Z 2256J-6 are based on the ISO standard, with only minor differences, if any. This standard specifies use of a 10mm diameter hole created with a 12% clearance. The sample containing the hole is clamped in place, and a conical punch having a 60 degree apex angle expands that initial hole (Figure 1). The test stops after observation of a through-thickness crack or upon experiencing a load-drop exceeding a critical threshold (Figure 2). The hole expansion ratio (HER), also known as the Hole Expansion Capacity (HEC), is simply the percent expansion of the diameter of the initial hole, typically shown as the Greek letter lambda, λ.

Figure 1: Schematic of Hole Expansion Test.A-10

Figure 2: Expanded Edge at the end of a Hole Expansion Test performed using a conical punch. The arrow points to the through-thickness crack that ended the test.E-2

The sample preparation and testing requirements of ISO 16630 are well-defined for good reason. Factors known to influence the hole expansion ratio include:

Even with these rigorously defined procedures, the test results can be heavily influenced by specimen preparation technique, specific test parameters, and human subjectivity – in other words, poor gage R&R (repeatability and reproducibility). For example a group of European steel researchers reported “an unacceptably large difference between labs” with regard to hole expansion testing. They ultimately concluded that the “difference is too large for the method to be useful in practice”.

A-76

Testing sheet steels of different thicknesses in a laboratory setting requires having multiple punches and/or dies of different diameter to maintain a consistent clearance, which is based on a percentage of the sheet thickness tested.

In production, the punch-to-die clearance can change during the life of the part, both from tooling wear as well as press misalignment. There is the additional risk that clearance can vary around the perimeter of the cut section, leading to inconsistent performance. Increasing sheet metal strength magnifies this issue.

The method used to create the free edge influences the edge quality. Improved edge quality and reduced mechanical work hardening of the edge is achieved by laser cutting, EDM cutting, water jet cutting, or fine blanking processes, and will typically improve the hole expansion ratio. Trim steel clearances, shear angles, tool steel types, and sharpness also impact hole expansion test results.

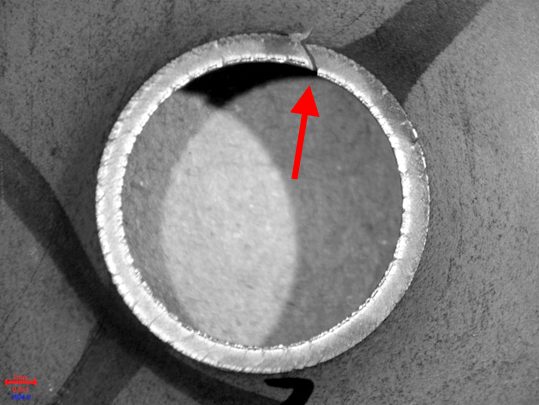

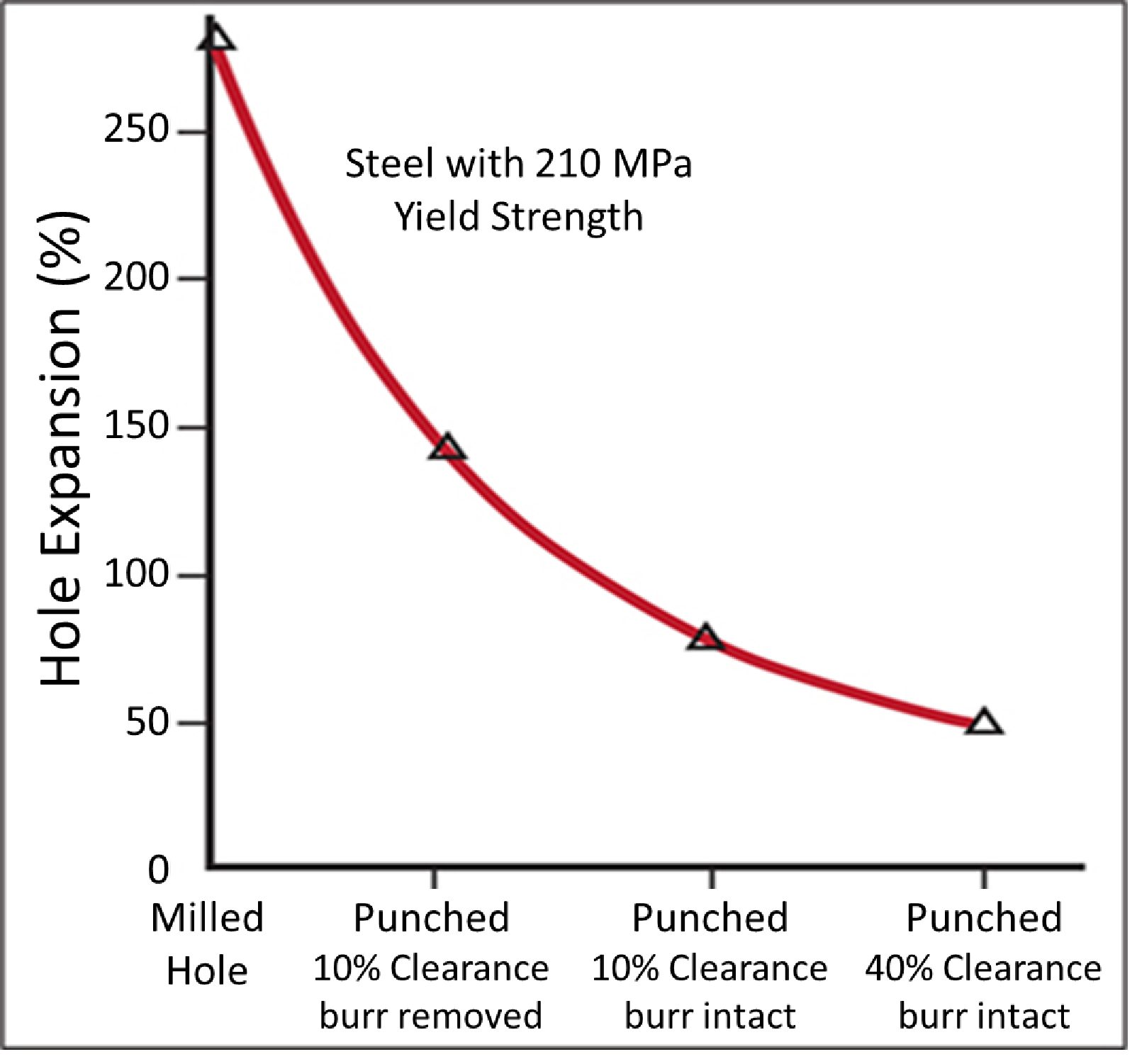

In the example shown in Figure 3, the hole expansion ratio is reduced from 280% for a milled or water jet edge down to 80% for a traditional cut edge. If clearances further increase – which could happen without proper tooling maintenance over the life of the part – the ability to expand a cut edge further decreases.

Figure 3: Hole Expansion Capacity Decreased as Edge Quality Decreases. (Based on data from Citation H-1.)

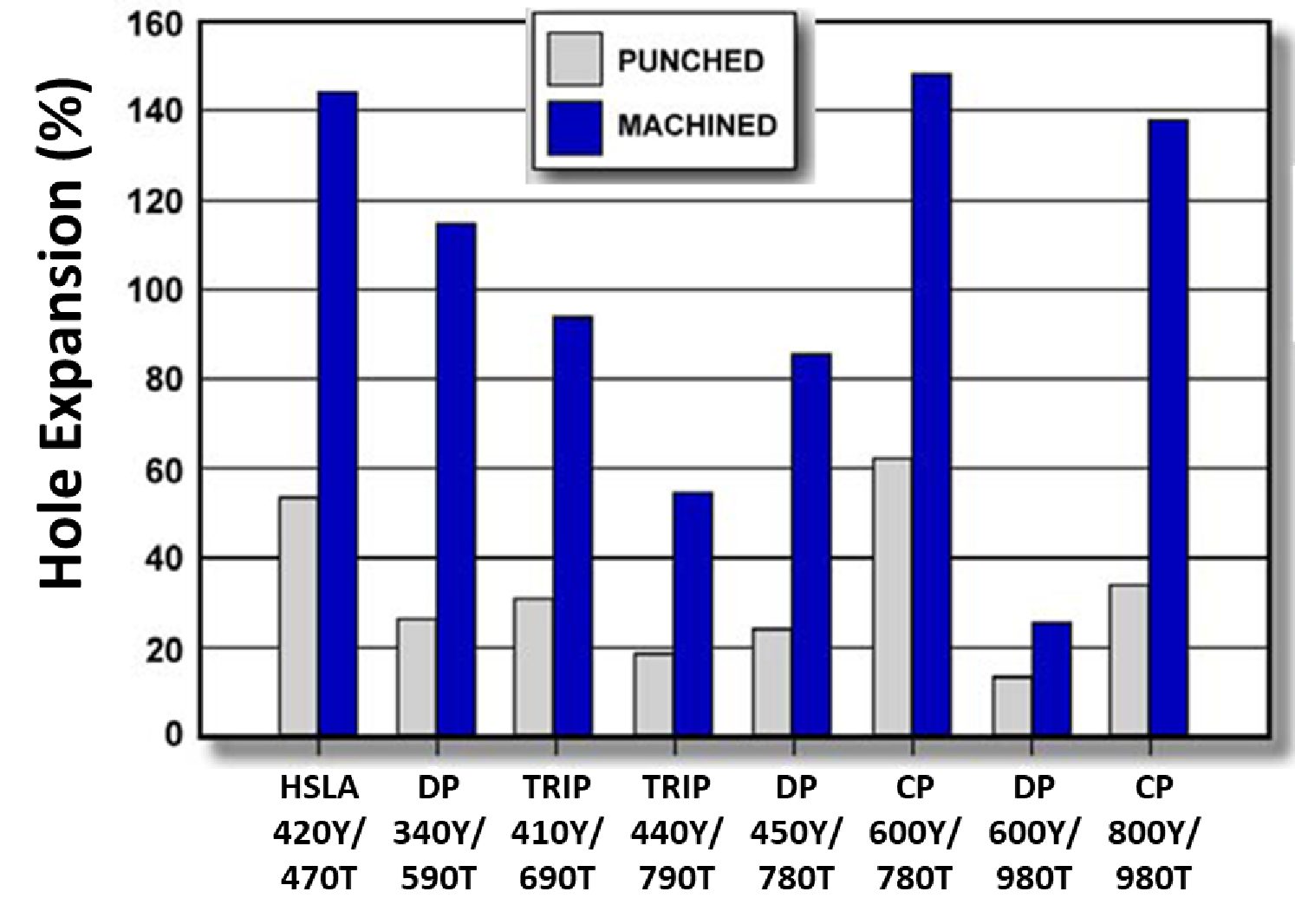

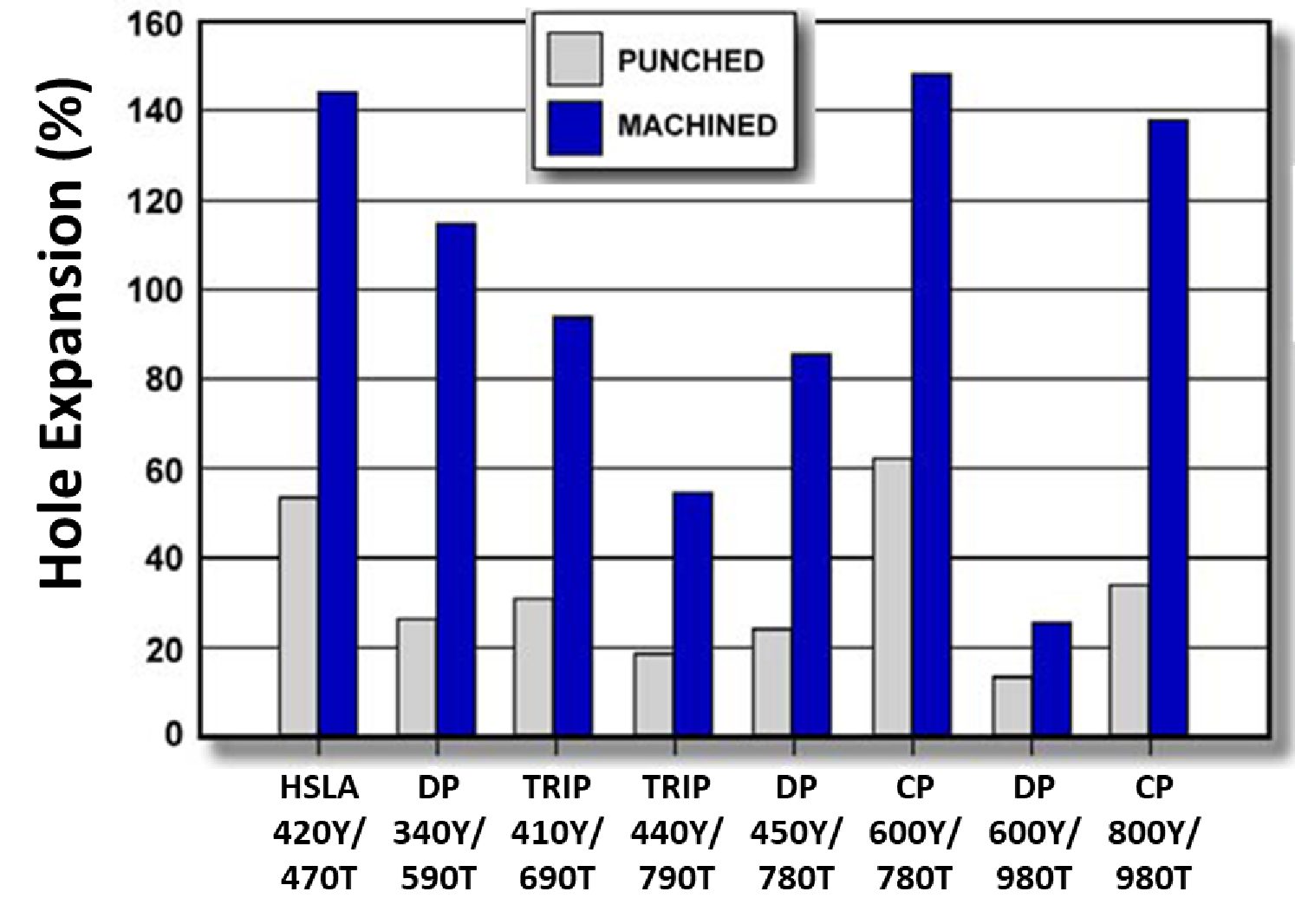

Figure 4 highlights the effect of punched vs machined holes, showing the edge damage from punching lowers the hole expansion capability. This edge damage becomes a key component of what is known as the Shear Affected Zone, or SAZ. DP steels and TRIP steels have a large hardness difference between the constituent phases, and therefore are associated with lower hole expansion ratios than HSLA and CP steels, where the phases are of more similar hardness. The influence of the metallurgical phase hardness difference is explored here. Detailed studies of sheared edge stretchability as a function of clearance, edge preparation, and grade are shown in Citations K-6 and K-10.

Figure 4: Hole expansion test results comparing punched and machined holes showing effect of damage to edge stretchability. (Based on data from Citation V-1.)

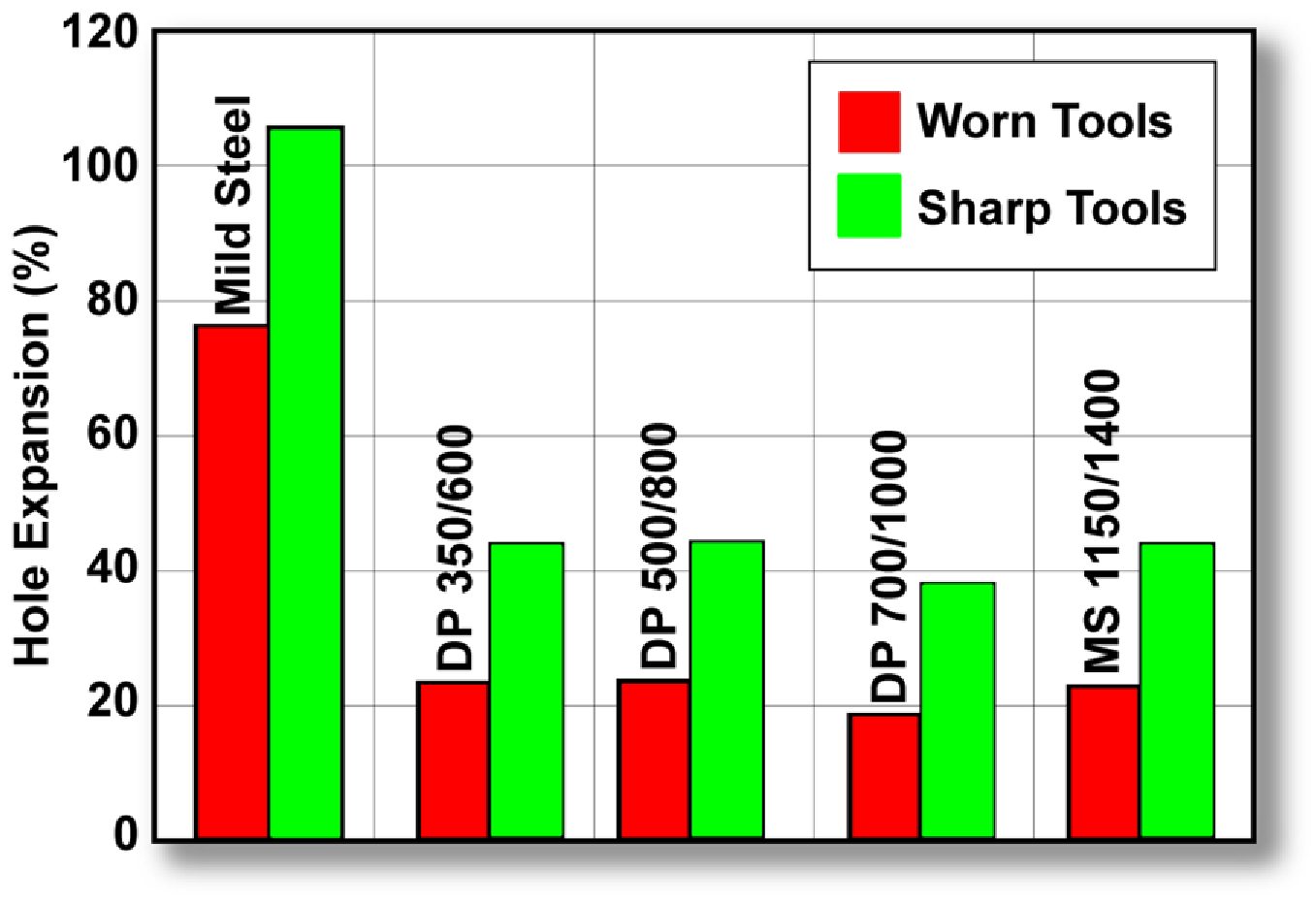

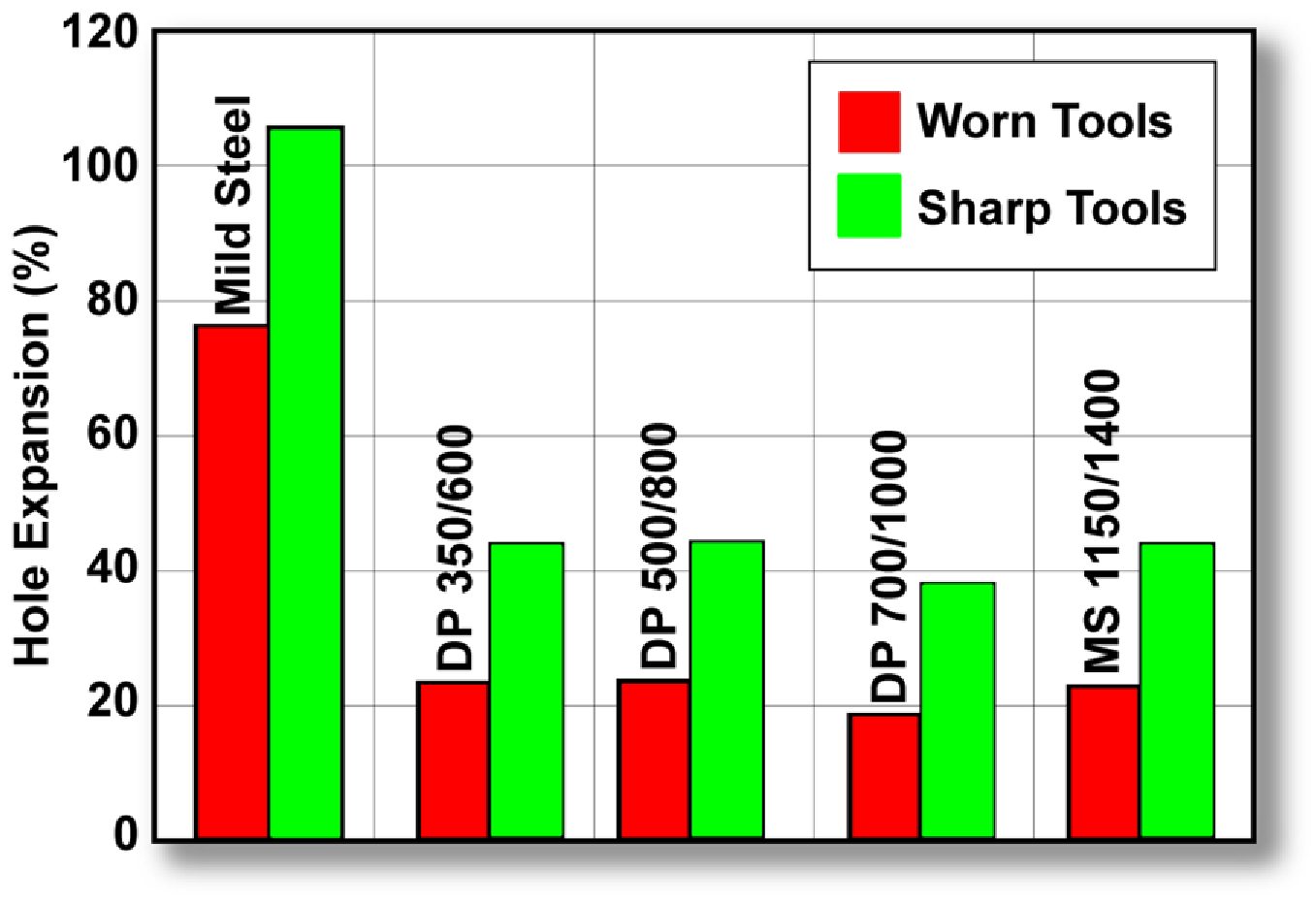

Over time, the targeted edge quality degrades and targeted clearance changes without proper attention. A study documented in Citation C-1 evaluated the hole expansion ratio created by hole punching tools as they wore in a production environment. Tools evaluated were made from 60 HRC uncoated Powder Metallurgy tool steels. Data in Figure 5 show the percent hole expansion from newly ground punches and dies (Sharp Tools) and from used production punches and dies (Worn Tools). The radial clearance was 0.1 mm. A rust preventative oil was applied to the steels during the punching; a lubricant oil was applied during hole expansion. Tool wear and possible micro-chipping resulted in a poor edge condition. The clearance was not significantly affected, but the steel edges suffered cold work which dramatically affected their hole expansion results.

Figure 5: Impact of production tooling condition on hole expansion performance. (tests conducted w 50 mm diameter conical punch).C-1

Conclusions from Citation C-1 include:

- The best quality edge condition will produce the best results

- Tooling must remain sharp and damage-free to maintain the consistency in edge conditions.

- The burr should be in contact with the punch rather than on the freely-expanding side

- Hard and wear resistant tools, such as those produced from coated powder metallurgy (PM) tool steels, are highly recommended.

Additional information on tool materials can be found here and other articles in that category.

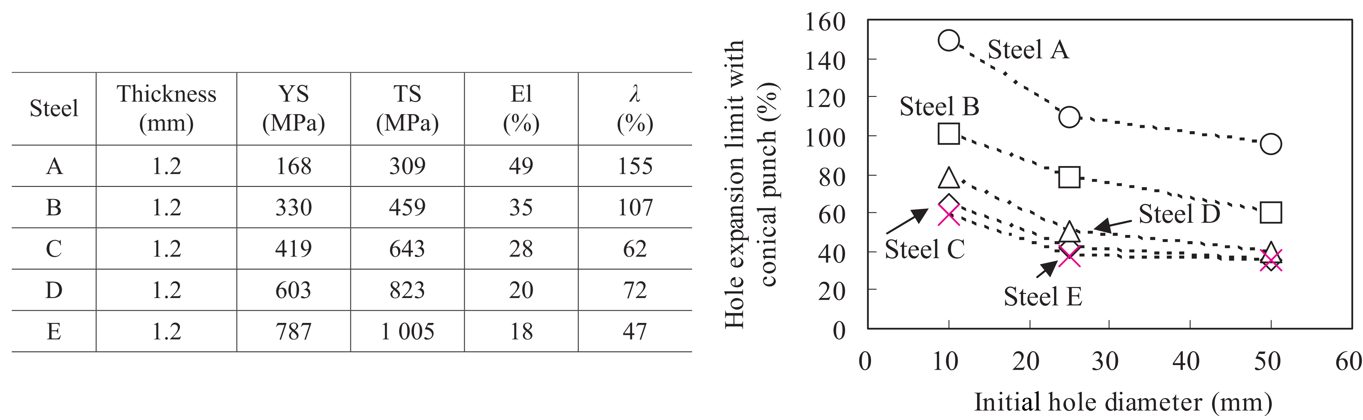

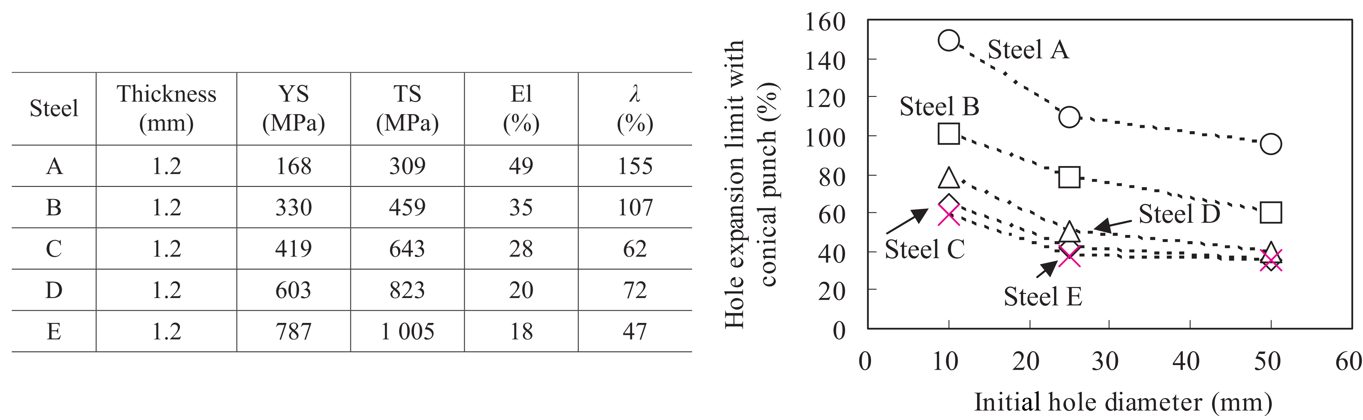

The ISO 16630 specificationI-9 eliminates one variable by prescribing the use of a 10 mm diameter hole, but it is important to understand that starting hole diameter influences the degree to which that hole can be expanded. A study that included mild steels to AHSS grades evaluated the effect of starting hole diameter.I-10 All steels were 1.2mm, punched with a clearance of 12.5%, and expanded with a conical punch having a 60° apex angle. As the starting diameter increases, the degree to which the hole can be expanded decreases, Figure 6. Note that as the strength increases, this effect appears to be minimized.

Figure 6: Hole Expansion Ratio Decreases as Initial Hole Diameter Increases.I-10

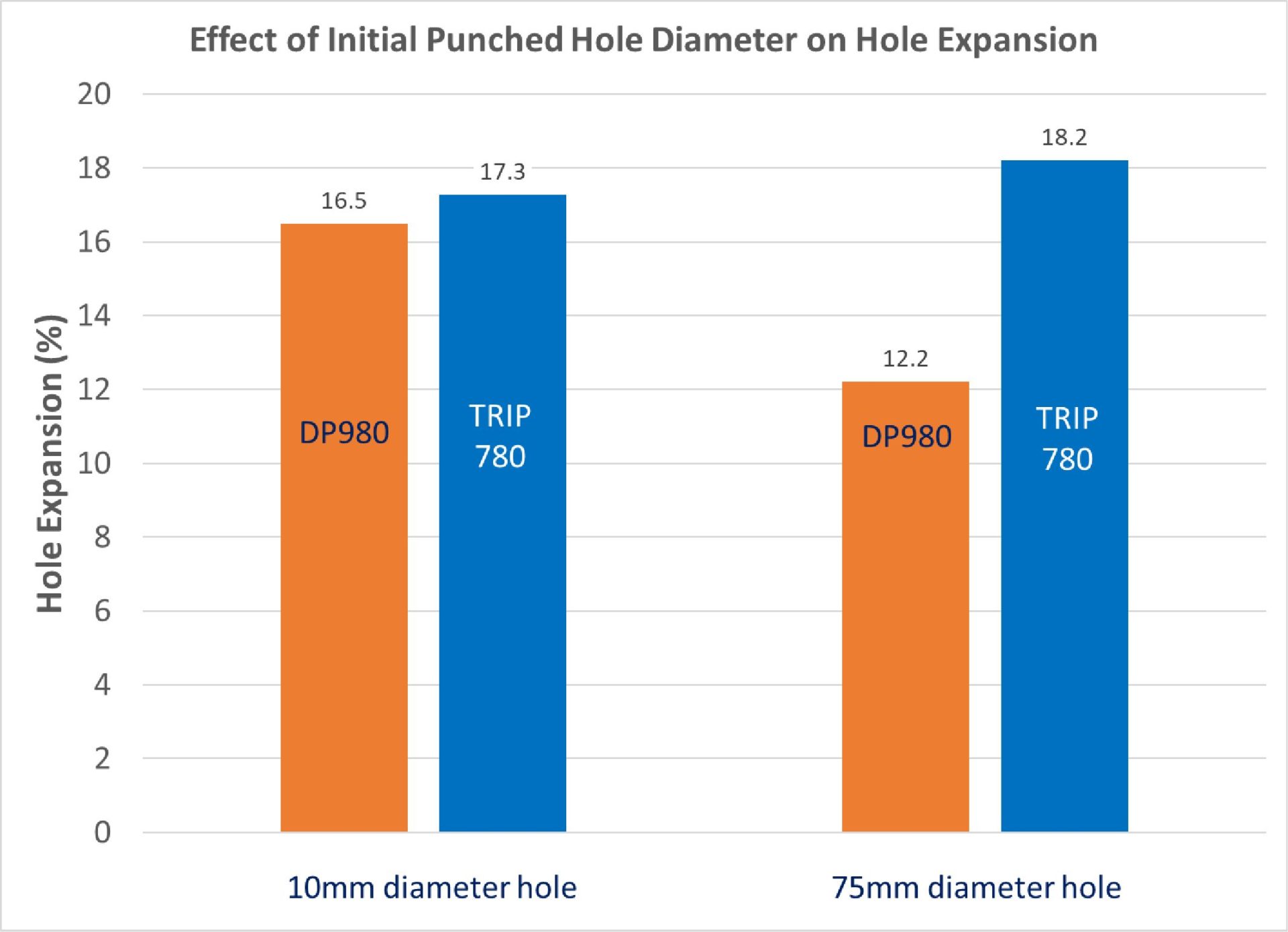

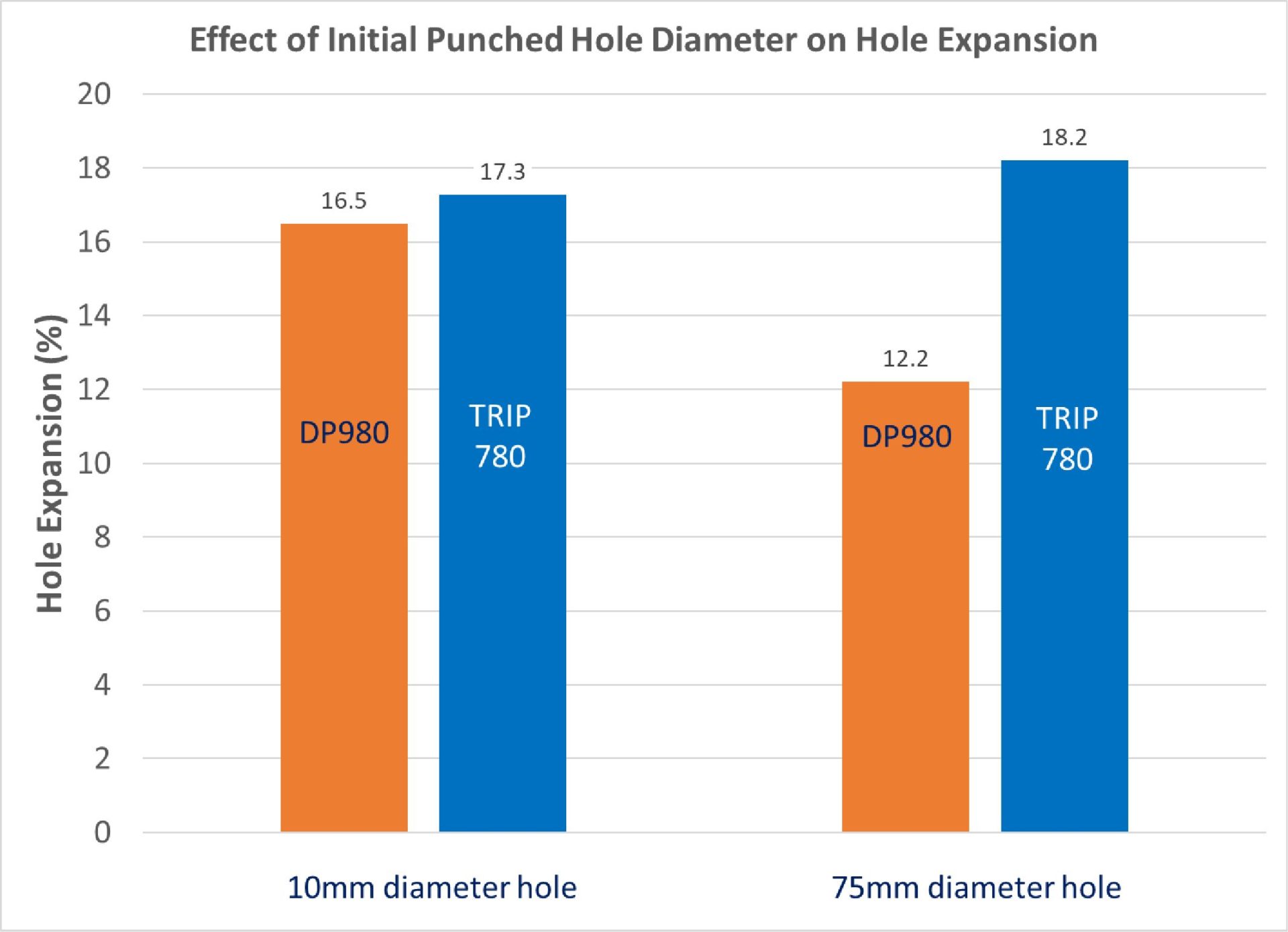

Increasing the starting hole diameter may help to distinguish between different grades.K-11 Similar hole expansion performance exists between DP980 and TRIP780 under ISO 16630 test conditions (punched 10 mm hole). It is easier to discern better performance in the TRIP780 product when performing a similar test with a 75 mm diameter punched hole (Figure 7).

Figure 7: Effect of Initial Punched Hole Diameter on Hole Expansion. (Based on Data from Citation K-11.)

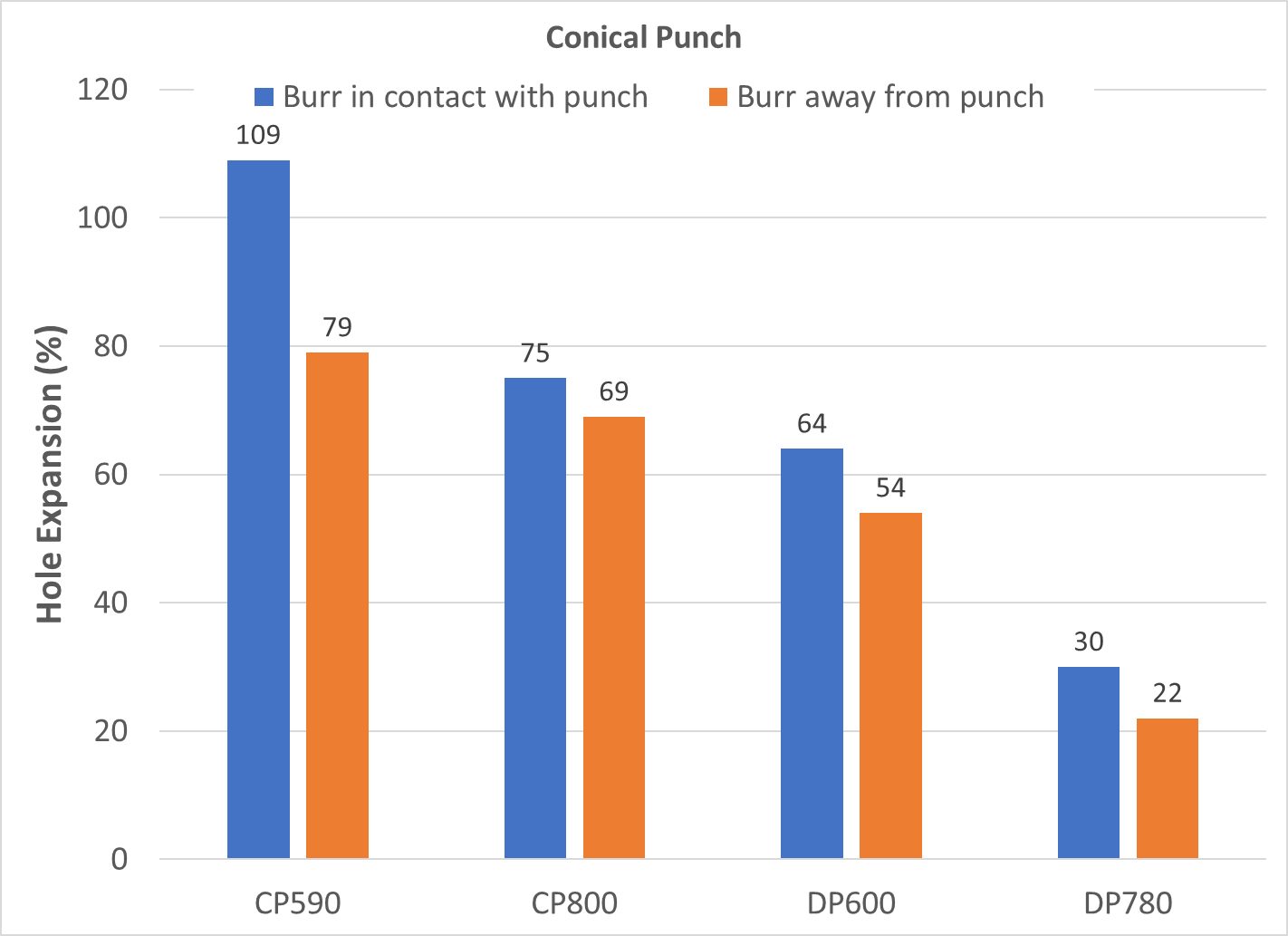

The position of the burr relative to the punch affects performance in a hole expansion test. Detrimental effects of an expanding edge are minimized If the burr is on the punch side. Having the burr on the punch side, rather than the freely expanding side, minimizes the detrimental effects of the expanding edge. The primary reason is the outer surface is in a greater degree of tension than the surface next to the punch.

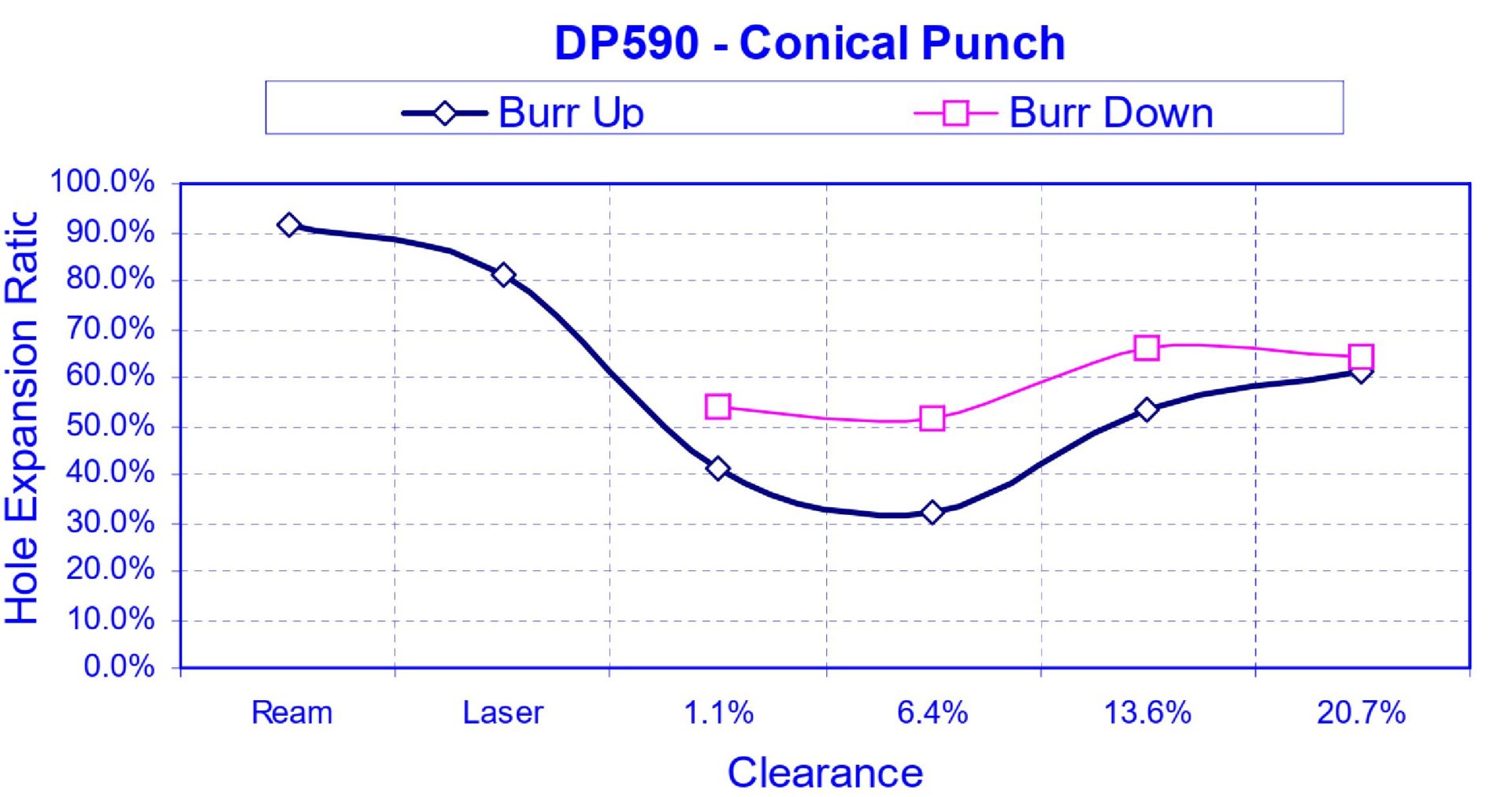

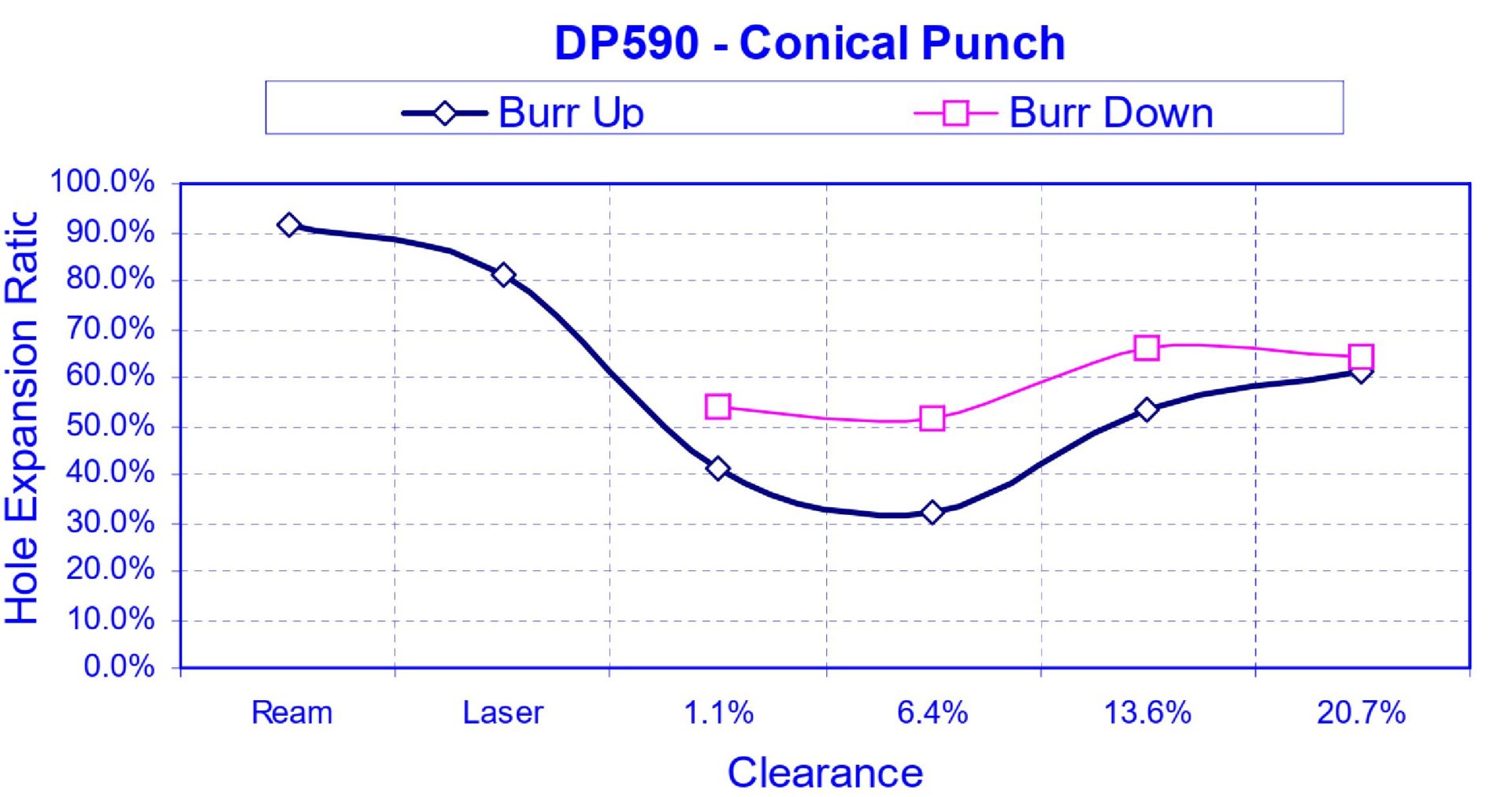

Figure 8 examines the effect of edge condition and clearance on DP 590 expanded with a conical punch.K-10 The data suggests that there could be up to a 20% increase in sheared edge extension capability just related to the burr position on holes punched with conventional clearances. This should be considered in die processing materials and designs sensitive to edge expansion.

Figure 8: The Effect of Burr Orientation on Hole Expansion as a Function of Clearance on DP590. “Burr Up” means away from the punch; “Burr Down” means in contact with the punch.K-10

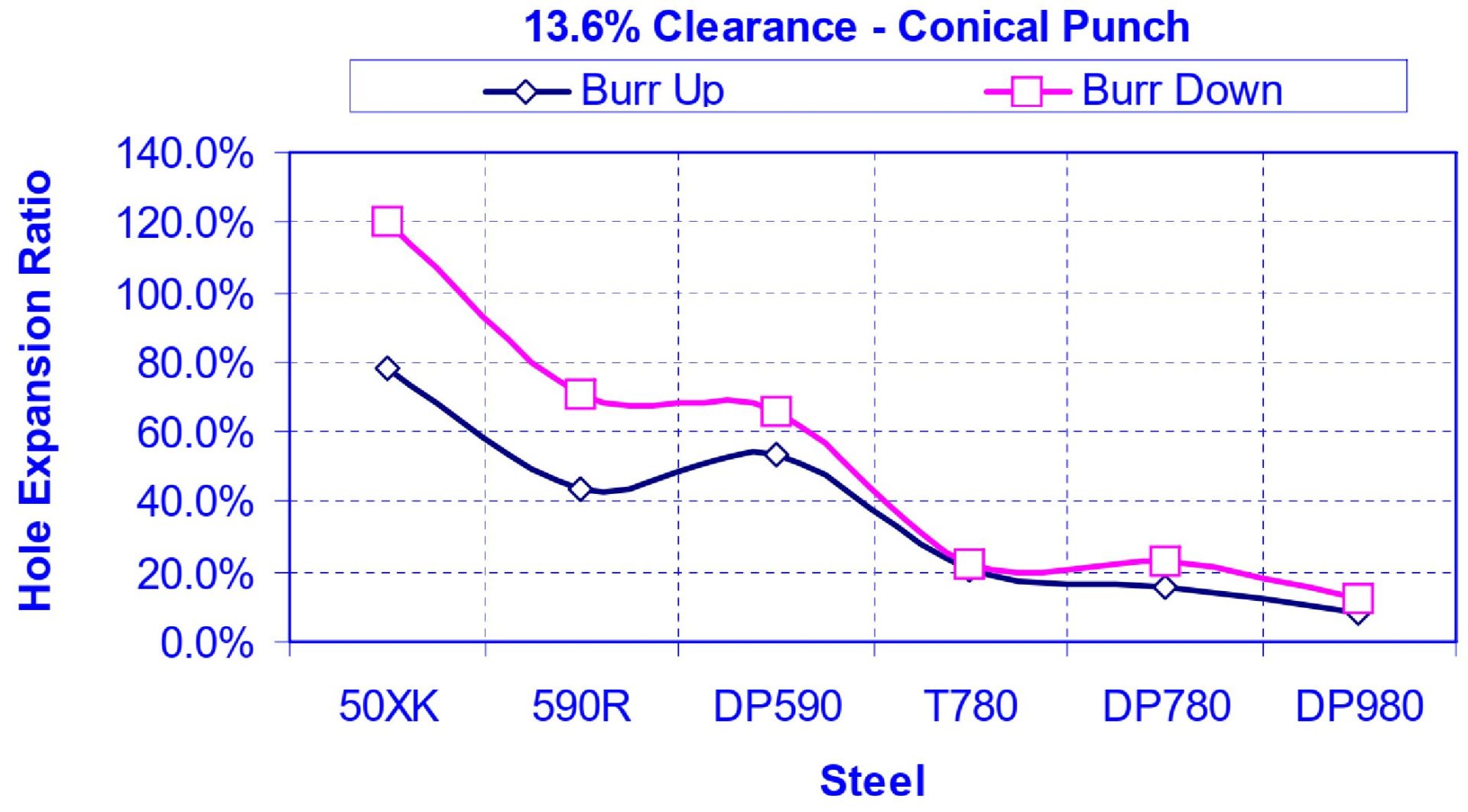

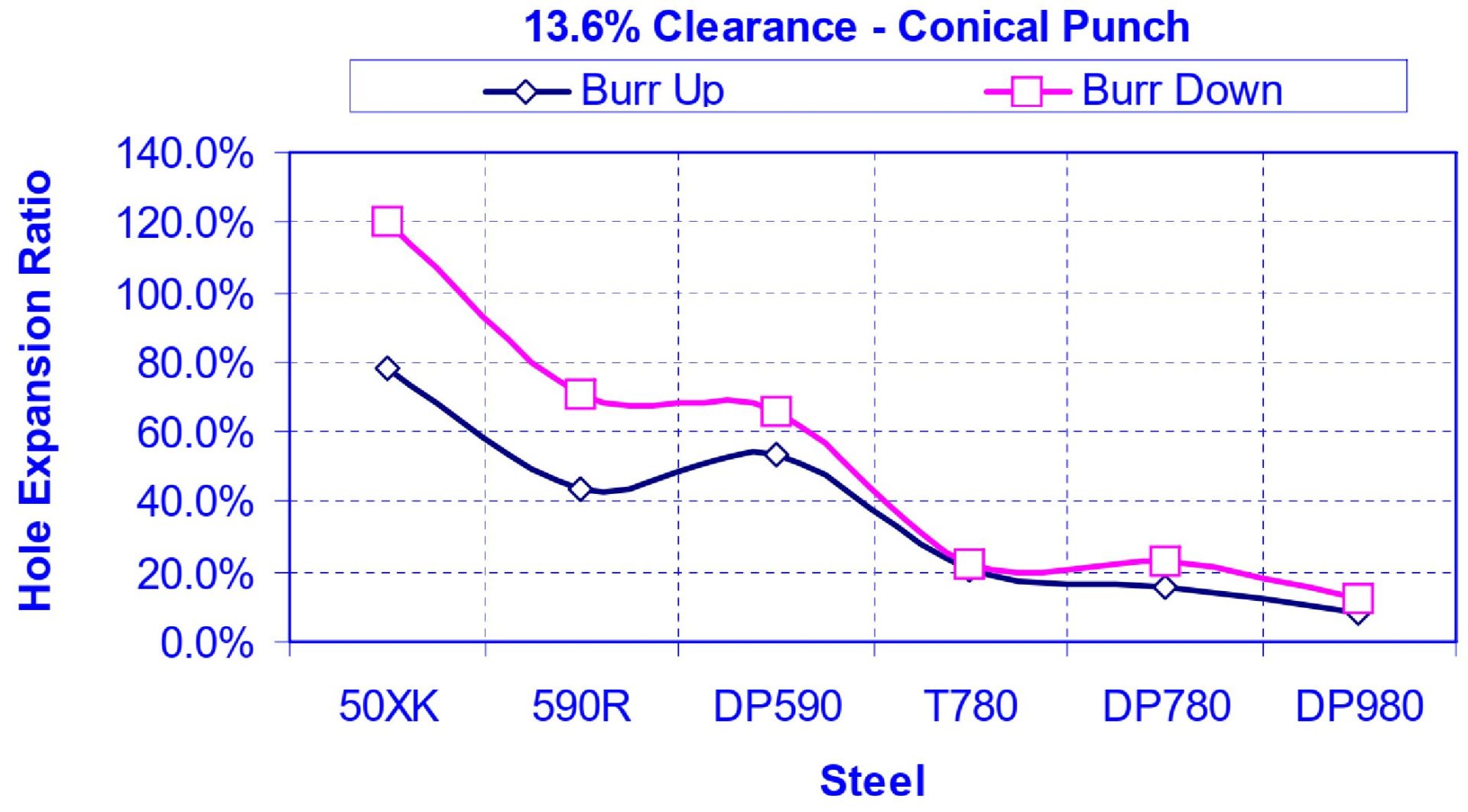

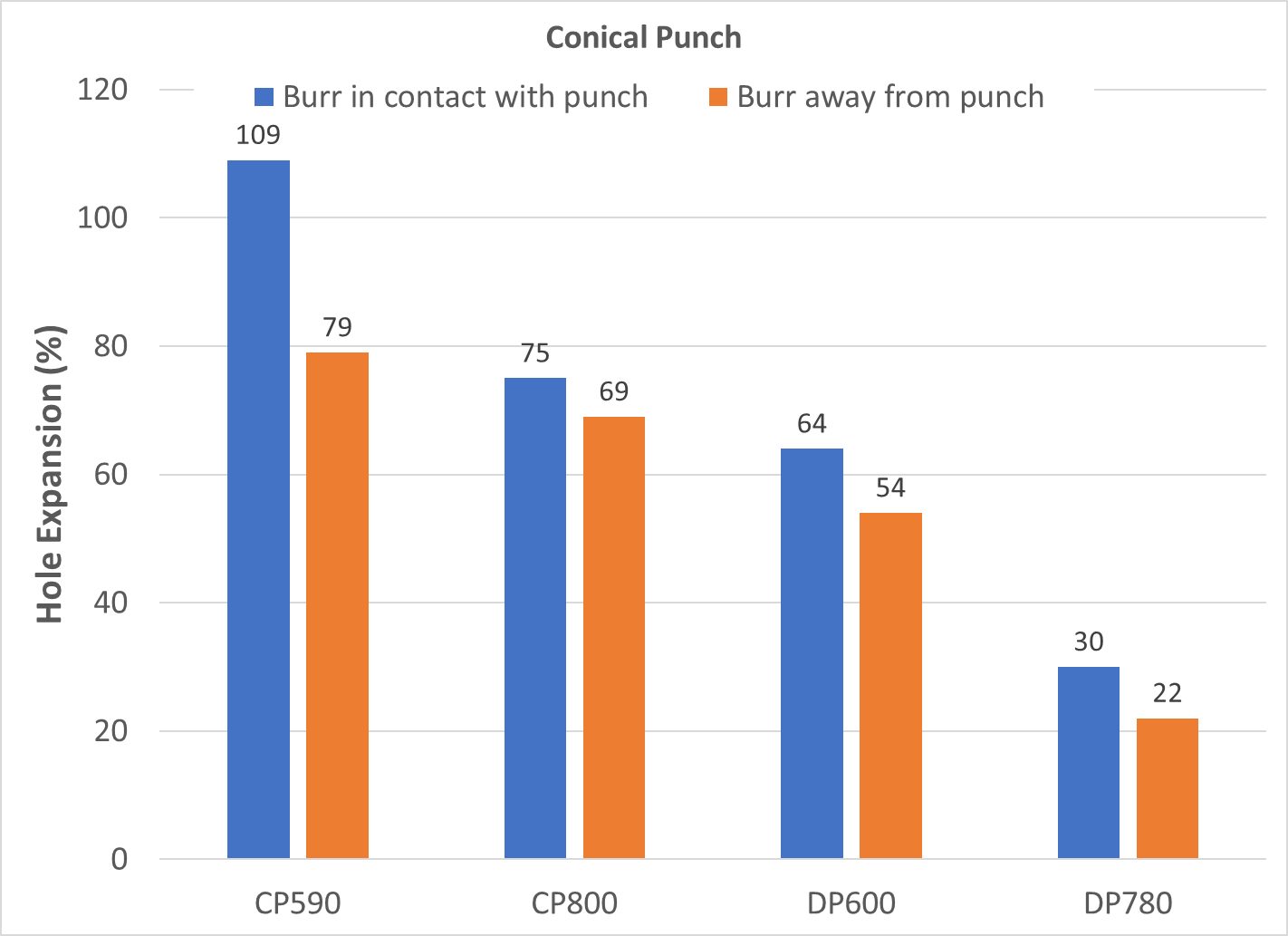

Shown in Figure 9 is the influence of burr orientation and material grade.K-10 The 50XK grade shown is HSLA 350Y/450T, where there is a significant improvement in the measured hole expansion related to the position of the burr relative to the punch. The magnitude of this difference decreases as strength increases, but persists for all grades tested.

Figure 9: The Effect of Burr Orientation on Hole Expansion as a Function of Different High Strength Steel Grades “Burr Up” means away from the punch; “Burr Down” means in contact with the punch.K-10

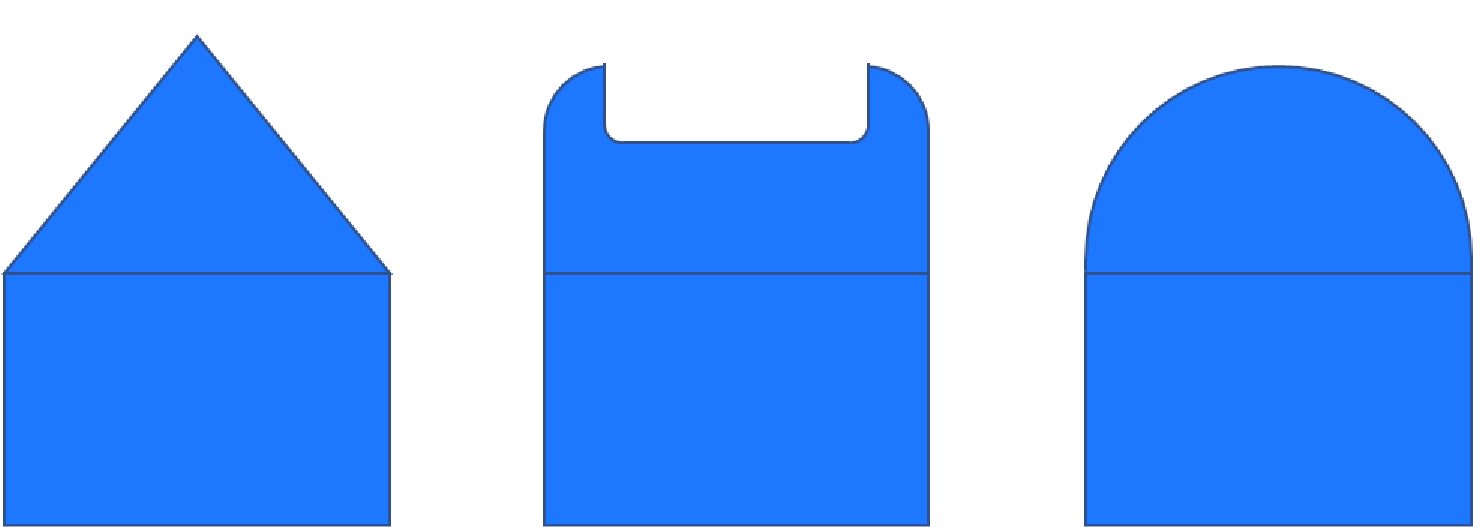

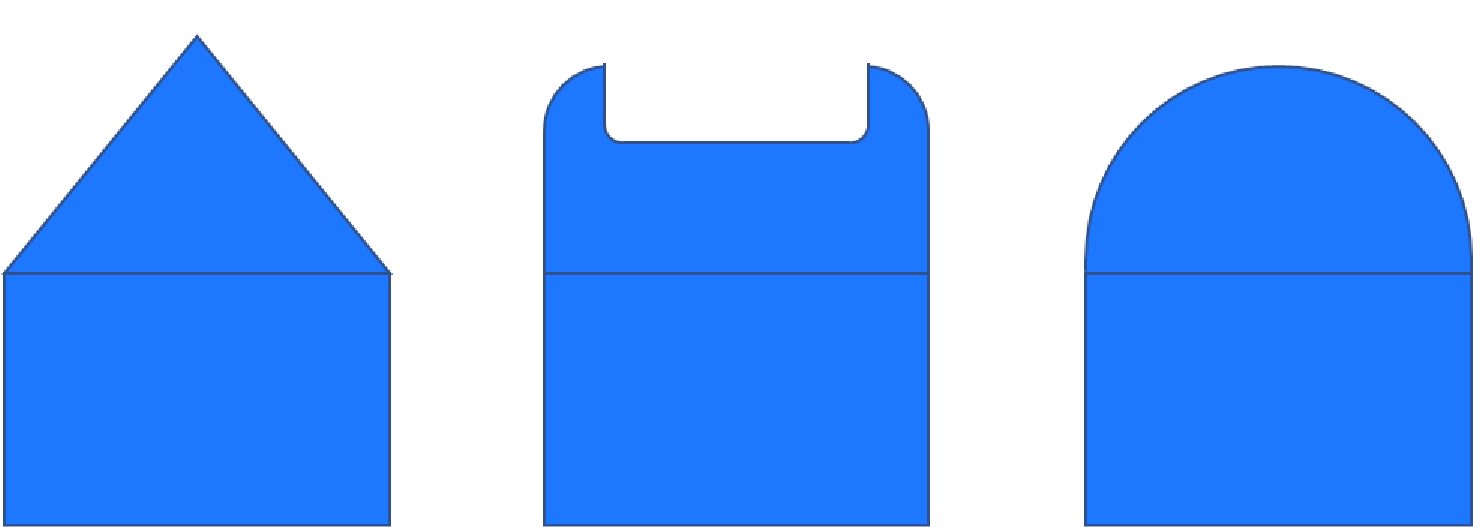

The shape of the punch used to expand the hole impacts the degree to which it can be expanded. Figure 10 shows generalizations of the three most-common shapes: a conical punch, a flat punch, and a hemispherical punch.

Figure 10: Sketches of Punches Used for Hole Expansion: Conical, Flat, and Hemispherical.

Metal motion and appearance changes depending on the type of punch used. Using a conical punch leads to the shape shown in Figure 11a, with a flat punch leading to the appearance shown in Figure 11b.S-3 The operations are sometimes described as hole expansion when accomplished with a conical punch, and hole extrusion with use of a flat punch.

Figure 11a: Sample appearance after testing with conical punch.S-3

Figure 11b: Sample appearance after testing with flat punch.S-3

The ISO 16630 hole expansion test specifies the use of a conical punch with a 60 degree apex angle. Here, the free edge undergoes stretching and bending. Using a flat punch instead of a conical punch eliminates the bending component, and all deformation is from only edge stretching. These strain state differences lead to different sheared edge extension performance, with greater expansion prior to cracking achieved with holes expanded using a conical punch. This improved performance with conical rather than flat punches has been attributed to the presence of the bending component.N-10 Edge condition does not appear to influence hole expansion capability when a flat bottom punch is used.

Shown in Figures 12 to Figure 15 are the effects of burr orientation and punch type, which vary as a function of metal grade. Figure 16 compares the performance of reamed holes when expanded with either conical or flat punches. Where the tested grades perform similarly when expanded with a flat punch, the conical punch leads to exceptional performance of reamed holes of 3 of the 4 grades. The relatively poor performance of the DP780 grade may be due to the hardness differences between the ferrite and martensite components, noting that there is more martensite in DP780 than DP 600. In the study from which the data was taken, the complex phase steels had a yield/tensile ratio of approximately 87%, while for the dual phase grades the yield/tensile ratio was approximately 60%.P-13

Figure 12: Effect of Burr Orientation on Hole Expansion from a Conical Punch. (Based on Data from Citation P-13.)

![Figure 13: Effect of Burr Orientation on Hole Expansion from a Flat Punch [Based on Data from Reference 11]](https://ahssinsights.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/Pasted-into-Hole-Expansion-Testing-Intro-31.jpg)

Figure 13: Effect of Burr Orientation on Hole Expansion from a Flat Punch. (Based on Data from Citation P-13.)

![Figure 14: Effect of Punch Type on Hole Expansion of Sheared Holes with Burr In Contact With The Punch [Based on Data from Reference 11]](https://ahssinsights.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/Pasted-into-Hole-Expansion-Testing-Intro-32.jpg)

Figure 14: Effect of Punch Type on Hole Expansion of Sheared Holes with Burr In Contact With The Punch. (Based on Data from Citation P-13.)

![Figure 15: Effect of Punch Type on Hole Expansion of Sheared Holes with Burr Facing Away From The Punch [Based on Data from Reference 11]](https://ahssinsights.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/Pasted-into-Hole-Expansion-Testing-Intro-33.jpg)

Figure 15: Effect of Punch Type on Hole Expansion of Sheared Holes with Burr Facing Away From The Punch. (Based on Data from Citation P-13.)

![Figure 16: Effect of Punch Type on Hole Expansion of Reamed Holes [Based on Data from Reference 11]](https://ahssinsights.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/Pasted-into-Hole-Expansion-Testing-Intro-34.jpg)

Figure 16: Effect of Punch Type on Hole Expansion of Reamed Holes. (Based on Data from Citation P-13.)

Figure 17 compares the simulation results from expanding a perfect edge (no burr, no strain) with a conical punch on the left and a spherical punch on the right.W-2 The color scale, based on a “damage” parameter, shows that a spherical punch results in a more uniform distribution of damage, especially at the edge. This suggests that the impact of burr orientation on hole expansion is less significant for this punch geometry.

Flanging with a conical punch causes high circumferential strain and high damage values at the outer edge. The inner edge of the sheet initially presses against the punch, and later stretches during flanging. Since cracks initiate at the fracture zone, using a conical punch with the burr facing the punch leads to a greater hole expansion capability than when having the burr in contact with a spherical punch.

Fracture initiates at the edge, and orienting the burr so that it is in contact with the punch leads to a greater hole expansion value.

Figure 17: Distribution of damage values in simulated hole expansion tests conducted with a conical punch (left image) and a hemispherical punch (right image).W-2

Improving Hole Expansion with New Punch Shapes

As explained above, the degree to which a sheared edge can be stretched before fracture is a function of many parameters, including the shape of the punch. Also contributing is the hardness uniformity of the microstructural phases, where grades with components having high hardness differences are associated with relatively lower hole expansion capability.

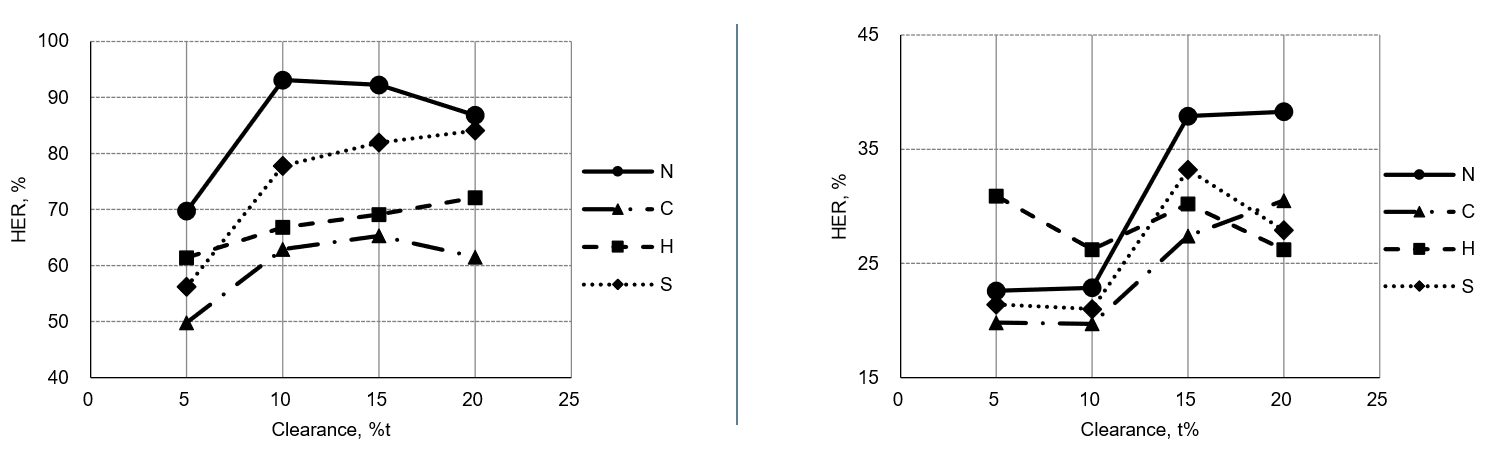

Researchers evaluated the effects of punch design and clearance on hole expansion capability of dual phase and ferrite-bainite steels, each with a tensile strength of approximately 780 MPa.L-47

In addition to a conventional flat punch face, other punch types studied were those with a beveled face, a humped shape, and a newly designed punch which combines the benefits of the prior two types. A chamfered or beveled punch is known to reduce punch forces and reverse snap-through loads, while at the same time improve edge quality and hole expansion by minimizing the hardness increases found in the shear affected zone.

Use of the humped punch (Figure 18) led to hole expansion improvements of up to 10%, compared with a conventional flat punch when testing either the DP or FB products. When comparing the edge characteristics, the humped punch results in an increased rollover zone. The authors attributed this to the hump geometry imposing axial tension on the steel during punching, thereby increasing stress triaxiality. Increases in stress triaxiality results in a reduction in effective stress even at the same average stress. This in turn lowers the plastic deformation at the sheared edge which minimizes edge fracture. For these reasons, the increases in stress triaxiality associated with the humped punch promotes higher levels of hole expansion.

Figure 18: Humped punch design used in Citation L-47.

A newly designed punch which combines a beveled and humped design (Figure 19) increases hole expansion by more than 30% in both dual phase and ferrite-bainite steels (Figure 20). As explained above, the newly designed punch is effective in promoting stress triaxiality and minimizing the plastic deformation near the sheared edge. Furthermore, the beveled design improves the shear affected zone (SAZ) characteristics, leading to improved sheared edge expandability as measured in a hole expansion test.

Figure 19: New punch design incorporating features of beveled and humped punches.L-47

Figure 20: Effect of punch type and clearance on the hole expansion ratio of 780 MPa tensile strength steels. Left graph represents ferrite-bainite steel; right graph represents a dual phase steel. Legend: N=new punch design; C=conventional; H=humped; S=shear (beveled).L-47

Correlation of Hole Expansion Ratio with Tensile Properties

The complexities of hole expansion testing, as well as relatively few laboratories with the necessary test equipment and expertise, have led researchers to look for a correlation between the hole expansion ratio and conventionally measured properties obtained from a tensile test like the yield and tensile strength, uniform and total elongation, n-value, and r-value. Researchers even studied manipulations such as the yield-to-tensile ratio, tensile strength multiplied by uniform elongation, and n-value multiplied by r-value. Unfortunately, none of these properties or combinations have suitable correlation with the hole expansion ratio.

Recent work has shown a promising correlation between the hole expansion ratio and the true thinning strain at fracture. Our article on true fracture strain, describes this in greater detail.

![Cutting, Blanking, Shearing & Trimming]()

Mechanical Properties

Elastic Modulus (Young’s Modulus)

When a punch initially contacts a sheet metal blank, the forces produced move the sheet metal atoms away from their neutral state and the blank begins to deform. At the atomic level, these forces are called elastic stresses and the deformation is called elastic strain. Forces within the atomic cell are extremely strong: high values of elastic stress results in only small magnitudes of elastic strain. If the force is removed while causing only elastic strain, atoms return to their original lattice position, with no permanent or plastic deformation. The stresses and strains are now at zero.

A stress-strain curve plots stress on the vertical axis, while strain is shown on the horizontal axis (see Figure 2 in Mechanical Properties). At the beginning of this curve, all metals have a characteristic linear relationship between stress and strain. In this linear region, the slope of elastic stress plotted against elastic strain is called the Elastic Modulus or Young’s Modulus or the Modulus of Elasticity, and is typically abbreviated as E. There is a proportional relationship between stress and strain in this section of the stress-strain curve; the strain becomes non-proportional with the onset of plastic (permanent) deformation (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: The Elastic Modulus is the Slope of the Stress-Strain Curve before plastic deformation begins.

The slope of the modulus line depends on the atomic structure of the metal. Most steels have an atomic unit cell of nine iron atoms – one on each corner of the cube and one in the center of the cube. This is described as a Body Centered Cubic (BCC) structure. The common value for the slope of steel is 210 GPa (30 million psi). In contrast, aluminum and many other non-ferrous metals have 14 atoms as part of the atomic unit cell – one on each corner of the cube and one on each face of the cube. This is referred to as a Face Centered Cubic (FCC) atomic structure. Many aluminum alloys have an elastic modulus of approximately 70 GPa (10 million psi).

Under full press load at bottom dead center, the deformed panel shape is the result of the combination of elastic stress and strain and plastic stress and strain. Removing the forming forces allows the elastic stress and strain to return to zero. The permanent deformation of the sheet metal blank is the formed part coming out of the press, with the release of the elastic stress and strain being the root cause of the detrimental shape phenomenon known as springback. Minimizing or eliminating springback is critical to achieve consistent stamping shape and dimensions.

Depending on panel and process design, some elastic stresses may not be eliminated when the draw panel is removed from the draw press. The elastic stress remaining in the stamping is called residual stress or trapped stress. Any additional change to the stamped panel condition (like trimming, hole punching, bracket welding, reshaping, or other plastic deformation) may change the amount and distribution of residual stresses and therefore potentially change the stamping shape and dimensions.

The amount of springback is inversely proportional to the modulus of elasticity. Therefore, for the same yield stress, steel with three times the modulus of aluminum will have one-third the amount of springback.

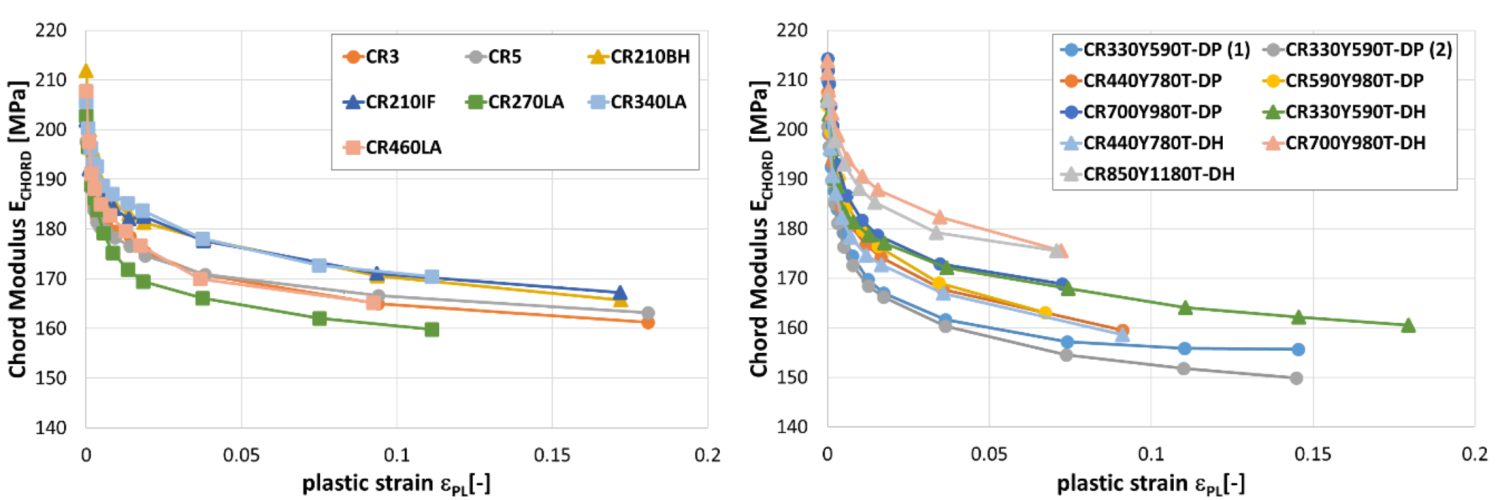

Elastic Modulus Variation and Degradation

Analysts often treat the Elastic Modulus as a constant. However, Elastic Modulus varies as a function of orientation relative to the rolling direction (Figure 2). Complicating matters is that this effect changes based on the selected metal grade.

Figure 2: Modulus of Elasticity as a Function of Orientation for Several Grades (Drawing Steel, DP 590, DP 980, DP 1180, and MS 1700) D-11

It is well known that the Bauschinger Effect leads to changes in the Elastic Modulus, and therefore impacts springback. Elastic Modulus determined in the loading portion of the stress-strain curve differs from that determined in the unloading portion. In addition, increasing prestrain lowers the Elastic Modulus, with significant implications for forming and springback simulation accuracy. In DP780, 11% strain resulted in a 28% decrease in the Elastic Modulus, as shown in Figure 3.K-7

Figure 3: Variation of the loading and unloading apparent modulus with strain for DP780K-7

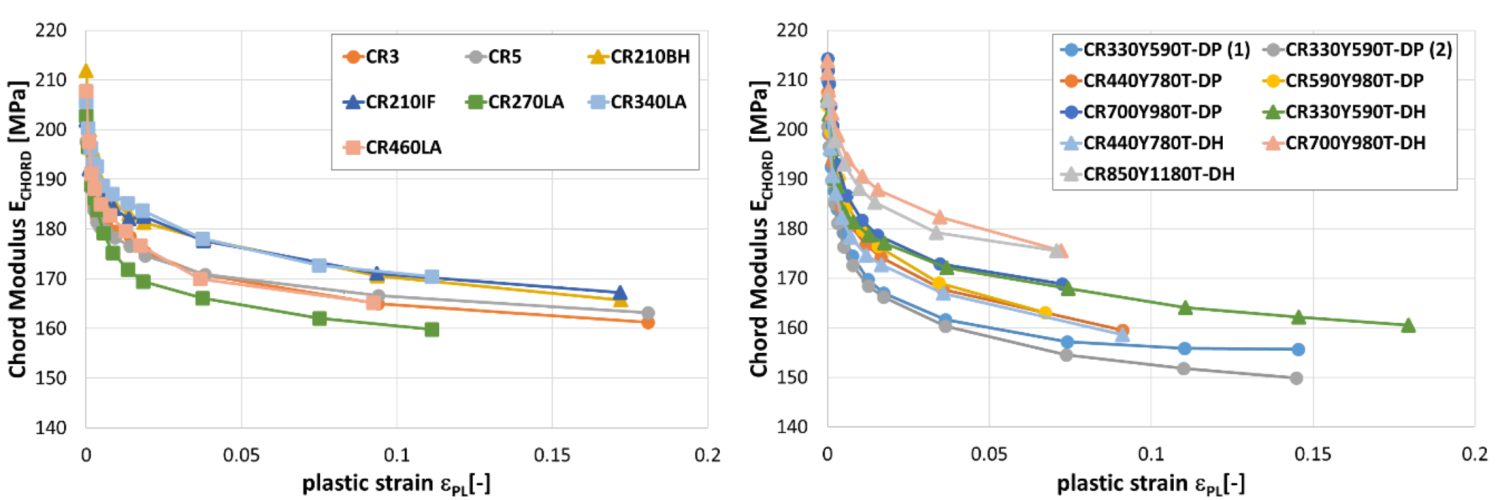

Another study documented the modulus degradation for many steel grades, including mild steel, conventional high strength steels, and several AHSS products.W-10 Data in some of the grades is limited to small plastic strains, since valid data can be obtained from uniaxial tensile testing only through uniform elongation.

Reduction in chord modulus for mild steels and conventional high strength steels (left) and for DP and DH steels (right).W-10

Reduction in chord modulus for CP, CH and MS steels (left) and for a selected of hot rolled steels (right).W-10

![Cutting, Blanking, Shearing & Trimming]()

1stGen AHSS, AHSS, Steel Grades

Complex Phase (CP) steels combine high strength with relatively high ductility. The microstructure of CP steels contains small amounts of martensite, retained austenite and pearlite within a ferrite/bainite matrix. A thermal cycle that retards recrystallization and promotes Titanium (Ti), Vanadium (V), or Niobium (Nb) carbo-nitrides precipitation results in extreme grain refinement. Minimizing retained austenite helps improve local formability, since forming steels with retained austenite induces the TRIP effect producing hard martensite.F-11

The balance of phases, and therefore the properties, results from the thermal cycle, which itself is a function of whether the product is hot rolled, cold rolled, or produced using a hot dip process. Citation P-18 indicates that galvannealed CP steels are characterized by low yield value and high ductility, whereas cold rolled CP steels are characterized by high yield value and good bendability. Typically these approaches require different melt chemistry, potentially resulting in different welding behavior.

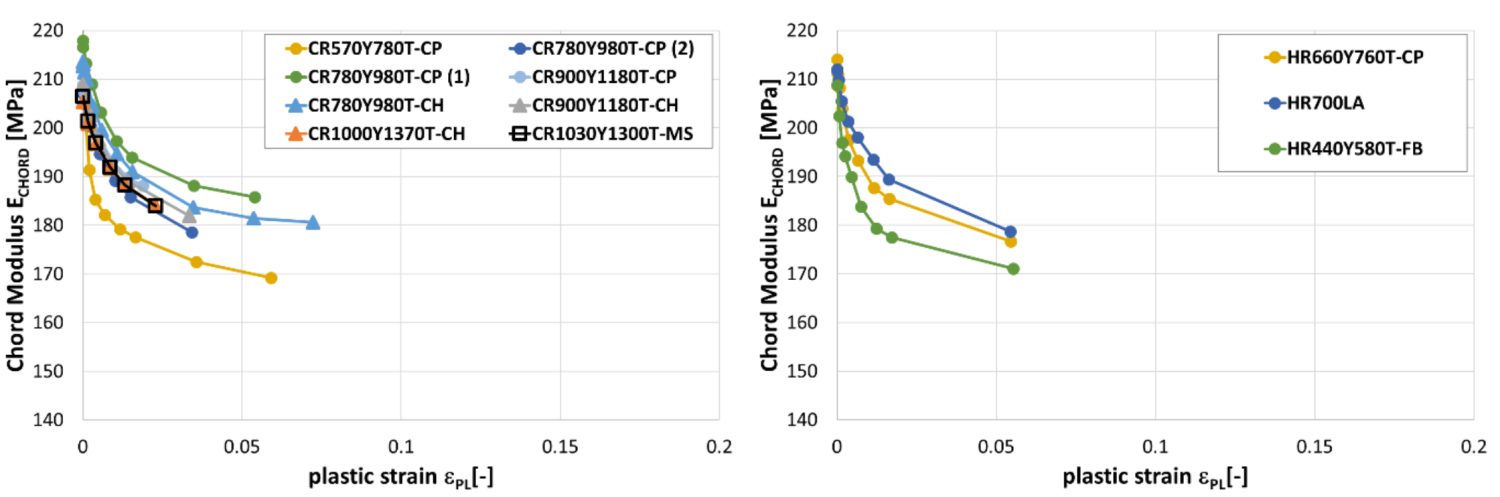

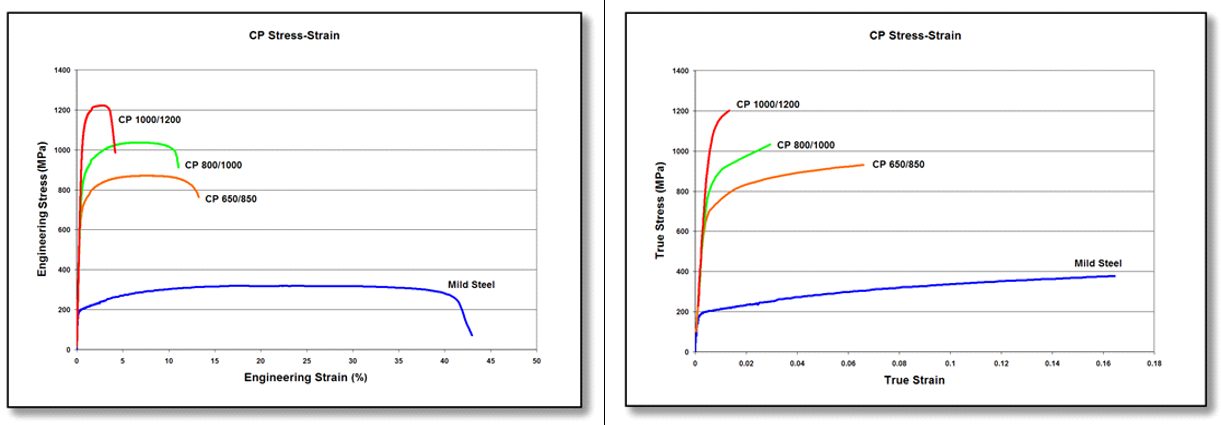

CP steel microstructure is shown schematically in Figure 1, with the grain structure for hot rolled CP 800/1000 shown in Figure 2. The engineering stress-strain curves for mild steel, HSLA steel, and CP 1000/1200 steel are compared in Figure 3.

Figure 1: Schematic of a complex phase steel microstructure showing martensite and retained austenite in a ferrite-bainite matrix.

Figure 2: Micrograph of complex phase steel, HR800Y980T-CP.C-14

Figure 3: A comparison of stress strain curves for mild steel, HSLA 350/450, and CP 1000/1200.

DP and TRIP steels do not rely on precipitation hardening for strengthening, and as a result, the ferrite in these steels is relatively soft and ductile. In CP steels, carbo-nitride precipitation increases the ferrite strength. For this reason, CP steels show significantly higher yield strengths than DP steels at equal tensile strengths of 800 MPa and greater. Engineering and true stress-strain curves for CP steel grades are shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4: Engineering stress-strain (left graphic) and true stress-strain (right graphic) curves for a series of CP steel grades. Sheet thickness: CP650/850 = 1.5mm, CP 800/1000 = 0.8mm, CP 1000/1200 = 1.0mm, and Mild Steel = approx. 1.9mm.V-1

Examples of typical automotive applications benefitting from these high strength steels with good local formability include frame rails, frame rail and pillar reinforcements, transverse beams, fender and bumper beams, rocker panels, and tunnel stiffeners.

Some of the specifications describing uncoated cold rolled 1st Generation complex phase (CP) steel are included below, with the grades typically listed in order of increasing minimum tensile strength and ductility. Different specifications may exist which describe hot or cold rolled, uncoated or coated, or steels of different strengths. Many automakers have proprietary specifications which encompass their requirements.

- ASTM A1088, with the terms Complex phase (CP) steel Grades 600T/350Y, 780T/500Y, and 980T/700Y A-22

- EN 10338, with the terms HCT600C, HCT780C, and HCT980C D-18

- VDA239-100, with the terms CR570Y780T-CP, CR780Y980T-CP, and CR900Y1180T-CPV-3

![Cutting, Blanking, Shearing & Trimming]()

3rdGen AHSS, AHSS, Steel Grades

First Generation Advanced High-Strength Steels (AHSS) are based on a ferrite matrix for baseline ductility, with varying amounts of other microstructural components like martensite, bainite, and retained austenite providing strength and additional ductility. These grades have enhanced global formability compared with conventional high strength steels at the same strength level. However, local formability challenges may arise in some applications due to wide hardness differences between the microstructural components.

The Second Generation AHSS grades have essentially a fully austenitic microstructure and rely on a twinning deformation mechanism for strength and ductility. Austenitic stainless steels have similar characteristics, so they are sometimes grouped in this category as well. 2nd Gen AHSS grades are typically higher-cost grades due to the complex mill processing to produce them as well as being highly alloyed, the latter of which leads to welding challenges.

Third Generation (or 3rd Gen) AHSS are multi-phase steels engineered to develop enhanced formability as measured in tensile, sheared edge, and/or bending tests. Typically, these steels rely on retained austenite in a bainite or martensite matrix and potentially some amount of ferrite and/or precipitates, all in specific proportions and distributions, to develop these enhanced properties.

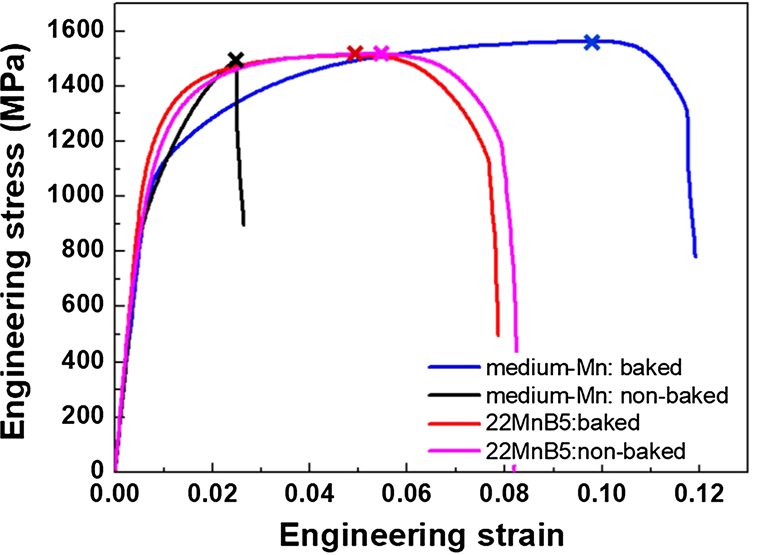

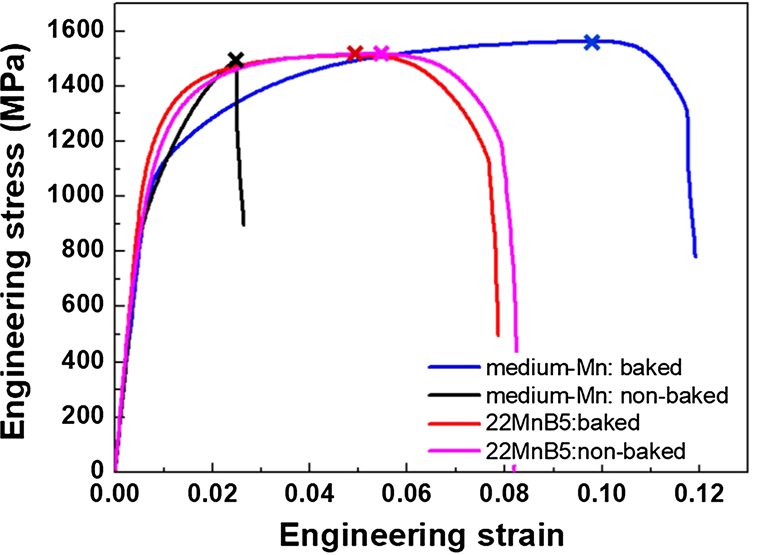

Individual automakers may have proprietary definitions of 3rd Gen AHSS grades containing minimum levels of strength and ductility, or specific balances of microstructural components. However, such globally accepted standards do not exist. Prior to 2010, one steelmaker had limited production runs of a product reaching 18% elongation at 1000 MPa tensile strength. Starting around 2010, several international consortia formed with the hopes of achieving the next-level properties associated with 3rd Gen steels in a production environment. One effortU-11, S-95 targeted the development of two products: a high strength grade having 25% elongation and 1500 MPa tensile strength and a high ductility grade targeting 30% elongation at 1200 MPa tensile strength. The “exceptional-strength/high-ductility” steel achieved 1538 MPa tensile strength and 19% elongation with a 3% manganese steel processed with a QP cycle. The 1200 MPa target of the “exceptional-ductility/high-strength” was met with a 10% Mn alloy, and exceeded the ductility target by achieving 37% elongation. Another effort based in EuropeR-22 produced many alloys with the QP process, including one which reached 1943 MPa tensile strength with 8% elongation. Higher ductility was possible, at the expense of lower strength.

3rd Gen steels have improved ductility in cold forming operations compared with other steels at the same strength level. As such, they may offer a cold forming alternative to press hardening steels in some applications. Also, while 3rd Gen steels are intended for cold forming, some are appropriate for the hot stamping process.

Like all steel products, 3rd Gen properties are a function of the chemistry and mill processing conditions. There is no one unique way to reach the properties associated with 3rd Gen steels – steelmakers use their available production equipment with different characteristics, constraints, and control capabilities. Even when attempting to meet the same OEM specification, steelmakers will take different routes to achieve those requirements. This may lead to each approved supplier having properties which fall into different portions of the allowable range. Manufacturers should use caution when switching between suppliers, since dies and processes tuned for one set of properties may not behave the same when switching to another set, even when both meet the OEM specification.

There are three general types of 3rd Gen steels currently available or under evaluation. All rely on the TRIP effect. Applying the QP process to the other grades below may create additional high-performance grades.

- TRIP-Assisted Bainitic Ferrite (TBF) and Carbide-Free Bainite (CFB)

- TRIP-Assisted Bainitic Ferrite (TBF) and Carbide-Free Bainite (CFB) are descriptions of essentially the same grade. Some organizations group Dual Phase – High Ductility (DP-HD, or DH) in with these. Their production approach leads to an ultra-fine bainitic ferrite grain size, resulting in higher strength. The austenite in the microstructure allows for a transformation induced plasticity effect leading to enhanced ductility.

- Quenched and Partitioned Grades, Q&P or simply QP

- Quenching and Partitioning (Q&P) describes the processing route resulting in a structure containing martensite as well as significant amounts of retained austenite. The quenching temperature helps define the relative percentages of martensite and austenite while the partitioning temperature promotes an increased percentage of austenite stabile room temperature after cooling.

- Medium Manganese Steels, Medium-Mn, or Med-Mn

- Medium Manganese steels have a Mn content of approximately 3% to 12%, along with silicon, aluminum, and microalloying additions. This alloying approach allows for austenite to be stable at room temperature, leading to the TRIP Effect for enhanced ductility during stamping. These grades are not yet widely commercialized.

TRIP Assisted Grades, like TRIP-Assisted Bainitic Ferrite (TBF)

and Carbide-Free Bainite (CFB)

During the slow cooling of conventional steels, austenite transforms into a microstructure containing alternating regions of ferrite and cementite. Note that cementite is the name given to iron carbide with the composition Fe3C. At higher magnification, this microstructure looks like Mother-of-Pearl, leading to its name of pearlite.

Depending on the chemistry and thermal profile, rapid controlled cooling produces new microstructures which are not achievable with slow cooling, including martensite, austenite, and bainite. Bainite consists of regions of dislocation-rich (higher strength) ferrite separated by austenite, martensite, and/or cementite. These phases within bainite have relatively small hardness differences, leading to improved local formability compared with conventional dual phase or TRIP steels. Producing a fully-bainitic microstructure is challenging, so bainite is usually accompanied by other phases, resulting in ferrite-bainite steels or complex phase.

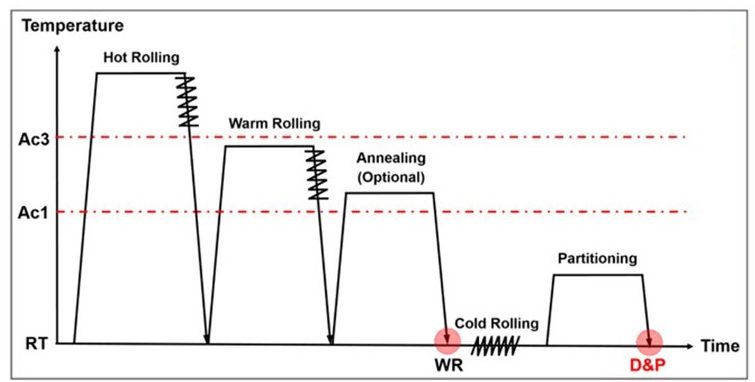

With an appropriate chemistry and use of specific thermal profiles capable of holding at specific temperatures and even reheating after quenching further reduces the size of these microstructural components, and essentially eliminates the production of the low-ductility cementite (iron carbide). Large “blocky” austenite, characteristic of 1st Generation TRIP steels, is minimized and instead thin fine submicron austenitic laths form (Figure 1).

Figure 1: On the left, the typical bainitic structure showing bainitic ferrite laths with interlath carbideS-96; On the right is the microstructure of TRIP Assisted Bainitic Ferrite / Carbide Free Bainite showing bainitic ferrite laths interwoven with thin films of untransformed retained austenite.C-31 αb is bainitic ferrite and γ is retained austenite. Note the slightly different magnification.

The fine components result in higher strength, similar to fine grain size being associated with increased strength. Since the ferrite is higher strength than conventional bainite due to the fine component size and even greater dislocation density, the component hardness difference is further minimized, leading to additional improvements in local formability. The austenite promotes the TRIP effect, resulting in greater uniform elongation and enhanced global formability. Combined, these features result in calling this microstructure either TRIP Assisted Bainitic Ferrite (TBF) or Carbide Free Bainite (CFB). Some sources suggest this is the same product as “Dual Phase with High Ductility,” abbreviated as DP-HD or simply DH.H-18, A-70, R-23, B-58 TBF, CFB, DP-HD, and DH are used interchangeably.

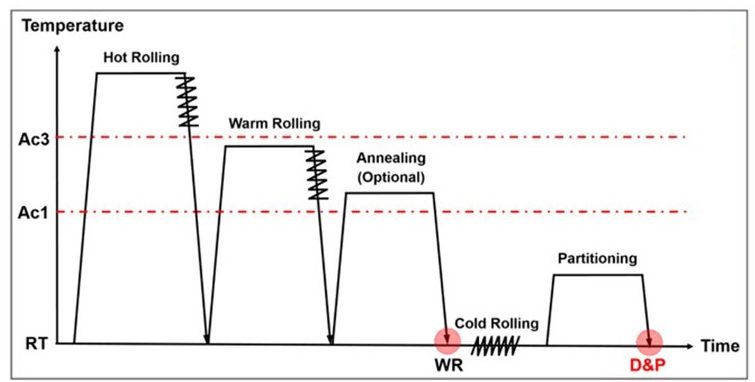

One potential processing route (Figure 2) may involve intercritically annealing in the two-phase austenite+ferrite region, cooling slightly to promote ferrite formation (1→2), and then quenching (2→3) to a temperature below the start of bainite formation (Bs) while remaining above the Ms temperature, the start of martensitic transformation. Once the targeted amount of bainite has formed in an isothermal overaging step (3→4), the steel is then quenched to room temperature (4→5).

Figure 2: Potential thermal cycle to produce TRIP assisted Bainitic Ferrite (Carbide-Free Bainite).

These steels are characterized by a good balance of strength and global formability (as measured by high TSxEL, uniform elongation, and total elongation combined with low YS/TS) against local formability (as measured by bend angle and hole expansion ratio).C-31 A YS/TS ratio of approximately 0.7, similar to DP steels, is a characteristic of these grades.H-59, C-31

These steels exhibit a significant bake hardening response. One study found a BH kick of over 200 MPa after a 4% prestrain and a bake cycle of 30 minutes at 200 °C. The total hardening response (strain hardening plus bake hardening) was almost 800 MPa.T-41 However, in production, this paint bake cycle is not likely to be practical due to paint over curing and the preference for faster cycle times. A different study evaluated TBF700Y/1050T and found after 15 minutes at 195 °C, samples prestrained to 4.5% had a BH kick of 150 MPa, with a total hardening response in excess of 350 MPa.B-60

Challenges exist when producing these grades with a galvanized or galvannealed coating. The relatively higher silicon content needed to suppress carbide formation may lead to difficulties galvanizing and with galvanized surface quality. Replacing silicon with aluminum helps with the coating issues, but makes the thermal cycle more complex. The chosen thermal cycle needs to be appropriate for the selected chemistry and targeted properties, and constrained by the capabilities of the existing mill equipment. Descriptions of the capabilities of equipment used in the production of cold rolled and galvanized AHSS are found elsewhere.K-43, B-59

The 2013 Infiniti Q50 is one of the earliest production applications for TBF 1180, where it formed 4% of the Body-In-White mass. Applications included A- and B-pillar reinforcements, sill reinforcements, and roof rail and side reinforcements. Adjusted welding techniques resulted in the same stress concentration as seen when welding mild steels.I-22, K-44 The same grade applied on the 2015 Nissan Murano in the A-Pillar Inner and reinforcements allowed numerous components to be downgauged from 1.6 mm to 1.2 mm compared with the prior version.C-32 1180TBF represented over 6% of the mass of the 2016 Nissan Maxima body-in-white, primarily applied in the A- and B-Pillar Reinforcements. Typically, 1.4 mm thick 980 grade steel was downgauged to 1.2 mm.C-33

A sample of commercially available TBF1180 was shown to have 946 MPa yield strength, 1222 MPa tensile strength, 18% elongation (JIS sample) , with a 40% hole expansion ratioM-54, which is consistent with the minimum properties listed by one automotive OEM: YS: 850 MPa minimum, TS: 1180 MPa minimum, elongation: 14% JIS minimum, and 30% minimum hole expansion ratio.F-36 Stretch formability as tested using a dome height evaluation was shown to be comparable to a conventional DP980 product, with deep drawability characterized by forming height in a cup draw test being superior to both conventional DP980 and DP1180.

Stress-strain curves of TBF700Y/1050T are found in the literature and presented in Figure 3 for reference. Note that these are random samples from a commercially available product tested at different laboratories, and therefore may not be representative of all products of this grade.

Figure 3: Stress strain curves of commercially available TBF 700Y/1050T. A) YS=775 MPa, TS = 1235 MPa, EL = 10%G-44; B) YS=751 MPa, TS = 1035 MPa, EL = 17%. Also shown is the pre-strain and bake hardening response for 1.0 mm thick blanks, tested after a 20 minute dwell time in a 170 °C furnace.B-60

The 2018 Infiniti QX50 SUV is an example of a vehicle believed to have TBF980 in the body structure.I-23 The product shown is called SHF980, and has a microstructure of approximately 50% ferrite, approximately 10% retained austenite, with the remainder as martensite/bainite, which is consistent with expectations for a TBF product. The thermal processing route to achieve this microstructural balance is consistent with a Quenching & Partitioning process (Figure 4). Both SHF980 and the reference DP980 are shown to have 660 MPa yield strength and 1000 MPa tensile strength. However, where DP980 has 15% elongation, SHF980 has 23% elongation. In addition, SHF980 is capable of 10% greater energy absorption over DP980 at the same thickness.I-23

Figure 4: Production and properties of SHF980, possessing a TBF microstructure.I-23

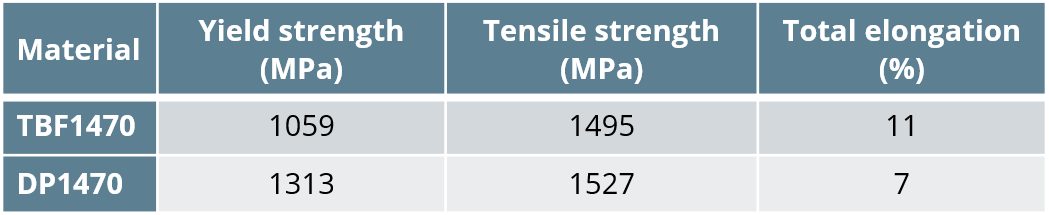

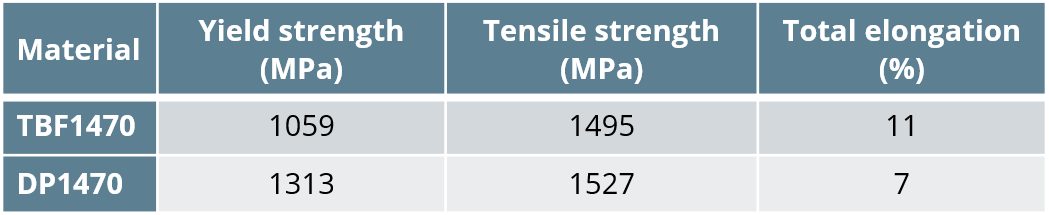

The highest strength TBF grade commercially available has 1,470MPa minimum tensile strength. Properties in Table 1 are compared with DP1470.

Table 1: Tensile properties of 1.2mm steels with 1470 MPa minimum tensile strength.M-55

Case Study: Production Application Where 3rd Gen Steels

Reduced Weight and Improved Performance

Toyota Motor Europe designed a part requiring a minimum tensile strength of 980 MPa, but when stamped using a conventional AHSS grade, experienced both global formability (necking) failures and local formability (sheared edge) failures (Figure 5). In the search for a grade which blended the high elongation of dual phase grades and the high hole expansion of complex phase grades, Toyota chose TBF980, a TRIP-assisted bainitic ferrite grade with the same yield and tensile strength of a conventional 980 grade but with improved elongation of approximately 14% and hole expansion of approximately 65%.A-1

Also reported were grade and design changes in a production vehicle where the strength of TBF980 allows for a 20% thickness reduction over the prior model. The improved formability of TBF980 facilitated a reduction in packaging space of the component, with the new design being 6% narrower and 20% shorter. Combined, these improvements reduced the vehicle weight by 1 kg.A-1

Figure 5: 980 MPa part with global and local formability failures. Converting the steel to TBF980 eliminated both types of splits. Image adapted from Citation A-1.

Quenched and Partitioned Grades, Q&P or simply QP

Quenching and partitioning (Q&P, or QP) describes a multi-step heat treatment which produces high tensile strength, high global ductility (total elongation) and high local ductility (hole expansion and bendability), compared with other similar strength steels. The QP process was first explained in 2003 by Speer et al.S-97, S-98, S-99

Among the unique aspects of the required thermal cycle is that after the first quench from the fully austenitized or intercritical annealing temperature, the steel may be reheated to a higher temperature, and then quenched to room temperature.

Figure 6 provides a general overview of the QP thermal cycle. After austenitization in either the single phase austenite region or the two-phase ferrite+austentite (intercritical annealing), the steel is quenched to a temperature below the start of martensitic transformation (Ms) but above the Mf (temperature at which all austenite has transformed to martensite), as indicated by segment 1→2. In the two-step QP process, the temperature is raised above Ms, shown in segment 2→3. No temperature increase is seen in the one-step QP process, meaning 2=3. Then the steel is held at this partitioning temperature for the appropriate time to generate the targeted microstructure and properties, segment 3→4. Once reached, the steel is quenched again (4→5), this time to a temperature below Mf, the temperature below which all transformation to martensite has occurred.

Figure 6: Thermal cycle for the Quenching and Partitioning Process.

The QP microstructure contains martensite and austenite. Ferrite is also present if intercritical annealing in the two-phase region is employed rather than in the single-phase austenitic region. The first quench forms a controlled volume fraction of martensite. With a QP chemistry containing C between 0.15 and 0.4%, Mn between 1.5 and 2.5%,and (Al + Si) around 1.5 wt.%, the quenching temperature usually lies in the range 200 to 350 °C.S-100 After raising to the partitioning temperature typically between 300 to 500 °CS-100, an isothermal hold allows carbon from the carbon-supersaturated martensite to diffuse into the untransformed austenite. This enriches the austenite with carbon while similarly depleting the martensite. The carbon enriched austenite increases its room temperature stability. Since the partitioning temperature above that required for martensite formation, some of the martensite transforms to tempered martensite. Tempered martensite provides high strength with more ductility than untempered martensite. After the partitioning step, the final quench results in the formation of fresh martensite.

When stamping parts from this steel, the austenite transforms to newly formed martensite through the TRIP effect, enhancing the ductility and strength. Adjusting the chemistry, quenching temperature, partitioning temperature, and partitioning time affects the amount, morphology, and stability of the retained austenite, leading to a wide range of potential properties.D-32 The microstructure of commercial Q&P steels is composed of martensite (50–80%) formed during quenching, ferrite (20–40%) formed as austenite slowly cools, and dispersed retained austenite (5–10%) stabilized by carbon enrichment during partitioning. Higher strength QP steels will have reduced amounts of ferrite.W-35 This is mostly consistent with a study highlighting commercially produced QP980 and QP1180 which showed that both products have approximately 10-12% retained austenite, with QP980 containing 56% ferrite / 32% martensite and QP1180 containing 21% ferrite / 69% martensite.W-36

There is no standard processing route with defined chemistry and temperatures. The complex thermal cycle needs to be appropriate for the selected chemistry and targeted properties, and constrained by the capabilities of the existing mill equipment. Citation K-43 presents descriptions of the equipment and capabilities used at one location. Process variants exist, such as a one-step approach using the same temperature for the initial quench and the partitioning.S-98 Other modifications allow for production of a Carbide-Free Bainitic structure during the first quench, improving the damage resistance due to additional strain-hardening capacity within the local plasticity deformation zone near the tips of micro-cracks.G-45

The Q&P process is applicable to other products as well, including stainless steelsM-56, M-57, S-101 and Press Hardening Steels.A-71, A-72, X-1 A one-step Q&P approach was applied to a laser welded blank with 22MnB5 and TRIP components, resulting in tailored properties to improve the intrusion resistance and energy-absorption capabilities in the pertinent regions.K-46

Complex phase steels with High Ductility (CP-HD, or CH) have similar microstructural constituents, along with bainite. Although CH steels reach high hole expansion values, they do not have the elongation levels typically associated with QP steels. Still, some sources equate CH and QP steels.H-18

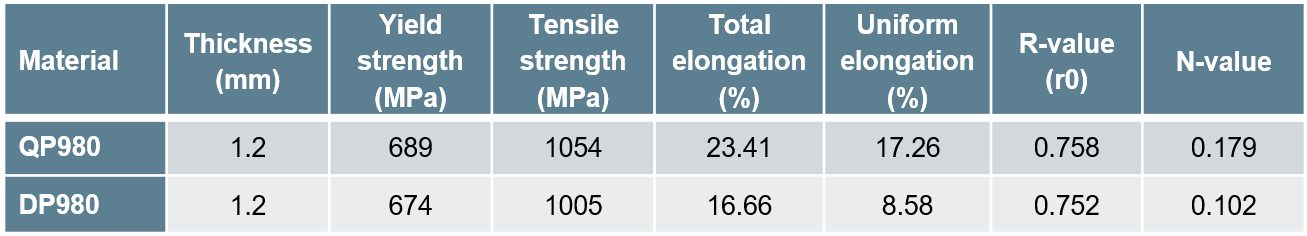

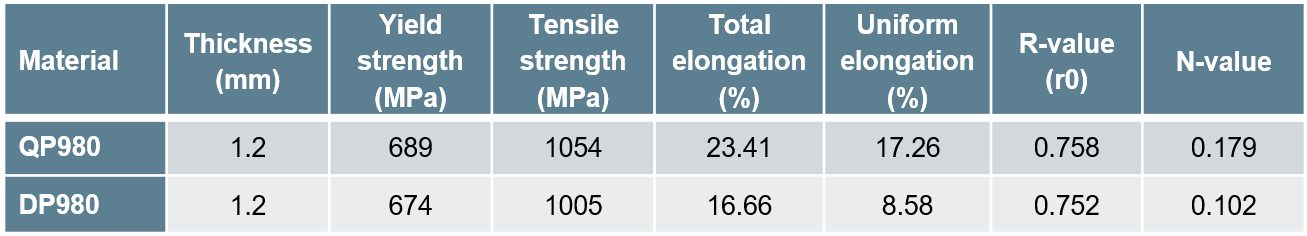

Two levels of Quenched & Partitioned steels are in global production, 980 MPa and 1180 MPa. The enhanced properties of QP steels offer benefits over similar-strength steels of other microstructures. Compared against Dual Phase steel with similar yield and tensile strength, a Quenched & Partitioned steel showed higher uniform elongation, total elongation, work hardening index, and FLC0, highlighted in Table 2 and Figure 7.C-34 A different production supplier of QP980 reports similar strength and elongation properties, with a targeted 23% hole expansion ratio.G-46

Table 2: Tensile properties of production DP980 and QP980.C-34

Figure 7: Comparison of Forming Limit Curves of production DP980 and QP980.C-34

QP980 is seeing expanded use in automotive production. The 2016 Chevrolet Sail from SAIC-GM represented the first application at General Motors.H-60 The 2021 Ford Bronco uses hot dip galvanized QP980 in five components of the front and rear floor assemblies.S-102 Sixty percent of the body structure of the 2021 Jeep Grand Cherokee L is made from AHSS, with some parts stamped from 3rd Gen steels.F-37

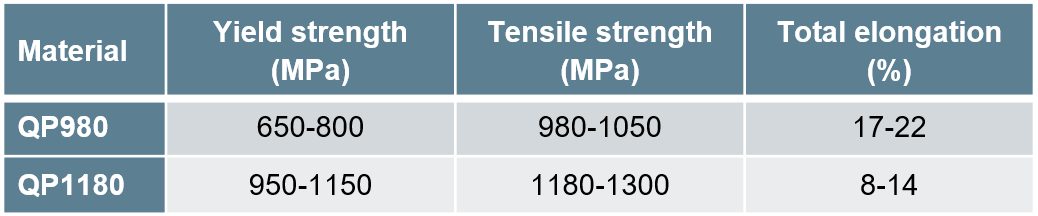

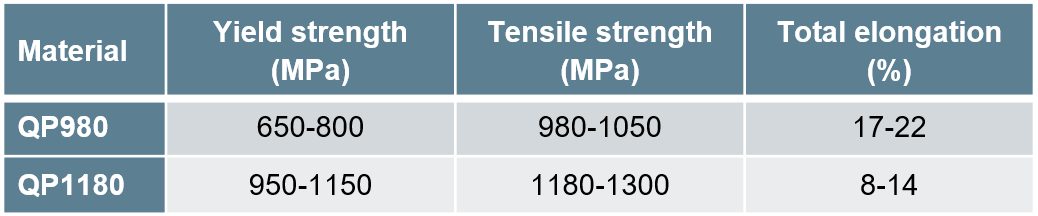

Table 3 contains typical mechanical property ranges for industrially produced QP980 and QP1180.W-35 A typical strain–stress curve of QP980 is shown in Figure 8.

Table 3: Typical mechanical property ranges for industrially produced QP980 and QP1180.W-35

Figure 8: Stress-strain curve of industrially produced QP980.W-35

Of course, there are additional characteristics beyond strength and elongation that impact successful use in manufactured products. Typical forming-limit curves for cold rolled QP980, DP780, and DP 980 steels are shown in Figure 9, highlighting that the formability of QP980 is comparable to that of DP780.

Figure 9: Forming-limit curves for 1 mm thick Q&P 980, DP 780, and DP 980.W-35

Figure 10 contains the results of high strain rate tensile testing, confirming that QP980 has positive strain rate sensitivity and therefore has the potential for improved crash energy absorption.

Figure 10: True stress-strain curves for QP980 generated at different strain rates.W-35

Sheared-edge ductility is also a concern in AHSS grades. Hole expansion of QP1180, QP980, and DP980 is compared in Figure 11, with similar results seen in QP980 and DP980. QP1180 had the highest hole expansion, possibly because of its microstructure containing components of relatively uniform hardness.

Figure 11: Hole expansion of QP1180, QP980, and DP980, generated from either punched or machined holes.W-35

The bending under tension test was used to determine the critical R/t value below which the risk for shear fracture increases. These experiments showed that critical R/t values of QP980 were close to those of other steels having 600 MPa tensile strength.W-35

Similar springback was observed in QP980 and DP980 when a 5 mm radius was used in the bending-under-tension test, with QP980 exhibiting less springback when a 12.7 radius die was used instead.W-35

General Motors provided stress-strain curves for production QP700/1180 tested at different strain rates (Figure 12), showing increases in strength and ductility as strain rates increase.H-60

Figure 12: Engineering stress-strain curves for QP700Y/1180T at different strain rates.H-60

A recent conference highlighted several applications (Figure 13) where thinner gauge QP980 replaced DP590 in General Motors vehicles.W-37

Figure 13: Replacing DP590 with QP980 allows for downgauging.W-37

The same presentationW-37 showed the example of QP980 replacing press hardening steels in B-pillar reinforcements and door anti-intrusion beams in a First Auto Works vehicle, Figure 14.

Figure 14: QP980 may replace press hardening steels in some safety applications.W-37

Medium Manganese Steels, Medium-Mn, or Med-Mn

Manganese has a lower density than iron, so using alloys with higher amounts of manganese truly creates lightweight products. 1st Generation steels typically contain no more than around 2% Mn. 2nd Generation TWIP steels have about 20% Mn. Lean medium-manganese (MedMn) steels typically use between 3% and 12% manganese along with silicon, aluminum, and microalloying additions.R-16, D-27, S-80, K-35 Aluminum in these steels further lowers the density.

No standard chemistry or processing route exists, but several studies use a thermal cycle similar to that seen with Q&P steels. This approach leads to a complex multiphase fine-grained microstructure. Compared with QP steels at the same strength levels, the higher manganese levels of Med-Mn steels promote greater amounts of retained austenite, and therefore greater ductility through the TRIP Effect. One study showed a combination of 1400 MPa tensile strength and a total elongation of 18%.S-103

One difference from the thermal cycle to produce QP steels used by some researchers to process Med-Mn steels is that after intercritical (two-phase) annealing, the quench is to room temperature rather than simply below Ms, the start of martensitic transformation.S-80 This is facilitated by the high levels of manganese, which adjusts the Mf below room temperature. Quenching a steel containing 0.25% C, 8.23% Mn, 1.87% Si, 0.05% Ni, and 0.24% Mo to room temperature and subsequently partitioning at 300 °C led to tensile strengths greater than 1800 MPa combined with total elongations of approximately 15%.S-80