![Uniform Elongation]()

Mechanical Properties

During a tensile test, the elongating sample leads to a reduction in the cross-sectional width and thickness. The shape of the engineering stress-strain curve showing a peak at the load maximum (Figure 1) results from the balance of the work hardening which occurs as metals deform and the reduction in cross-sectional width and thickness which occurs as the sample dogbone is pulled in tension. In the upward sloping region at the beginning of the curve, the effects of work hardening dominate over the cross-sectional reduction. Starting at the load maximum (ultimate tensile strength), the reduction in cross-sectional area of the test sample overpowers the work hardening and the slope of the engineering stress-strain curve decreases. Also beginning at the load maximum, a diffuse neck forms usually in the middle of the sample.

Figure 1: Engineering stress-strain curve from which mechanical properties are derived.

The elongation at which the load maximum occurs is known as Uniform Elongation. In a tensile test, uniform elongation is the percentage the gauge length elongated at peak load relative to the initial gauge length. For example, if the gauge length at peak load measures 61 mm and the initial gauge length was 50mm, uniform elongation is (61-50)/50 = 22%.

Schematics of tensile bar shapes are shown within Figure 1. Note the gauge region highlighted in blue. Up though uniform elongation, the cross-section has a rectangular shape. Necking begins at uniform elongation, and the cross section is no longer rectangular.

Theory and experiments have shown that uniform elongation expressed in true strain units is numerically equivalent to the instantaneous n-value.

Deformation Prior to Uniform Elongation is Not Uniformly Distributed

Conventional wisdom for decades held that there is a uniform distribution of strains within the gauge region of a tensile bar prior to strains reaching uniform elongation. Traditional extensometers calibrated for 50-mm or 80-mm gauge lengths determine elongation from deformation measured relative to this initial length. This approach averages results over these spans.

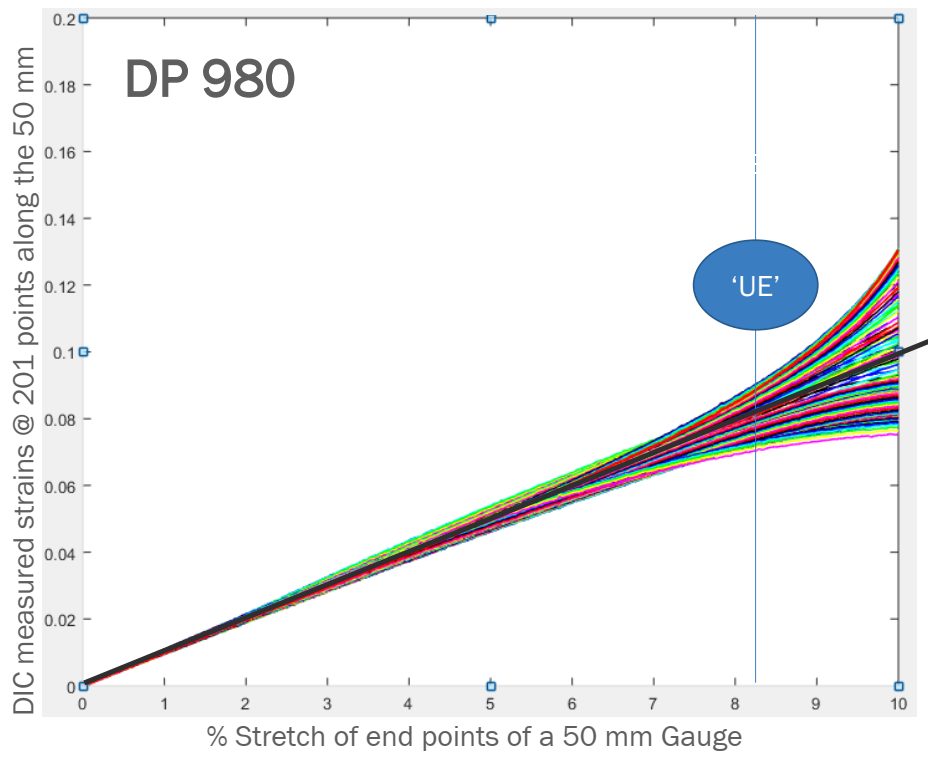

The advent of Digital Image Correlation (DIC) and advanced processing techniques allowed for a closer look. A studyS-113 released in 2021 clearly showed that each of the 201 data points monitored within a 50 mm gauge length (virtual gauge length of 0.5-mm) experiences a unique strain evolution, with differences starting before uniform elongation.

Figure 2: Strain evolution of the 201 points on the DP980 tensile-test specimen exhibits divergence beginning before uniform elongation—counter to conventional thinking.S-113

![Uniform Elongation]()

Mechanical Properties

N-Value, The Strain Hardening Exponent

Metals get stronger with deformation through a process known as strain hardening or work hardening, resulting in the characteristic parabolic shape of a stress-strain curve between the yield strength at the start of plastic deformation and the tensile strength.

Work hardening has both advantages and disadvantages. The additional work hardening in areas of greater deformation reduces the formation of localized strain gradients, shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Higher n-value reduces strain gradients, allowing for more complex stampings. Lower n-value concentrates strains, leading to early failure.

Consider a die design where deformation increased in one zone relative to the remainder of the stamping. Without work hardening, this deformation zone would become thinner as the metal stretches to create more surface area. This thinning increases the local surface stress to cause more thinning until the metal reaches its forming limit. With work hardening the reverse occurs. The metal becomes stronger in the higher deformation zone and reduces the tendency for localized thinning. The surface deformation becomes more uniformly distributed.

Although the yield strength, tensile strength, yield/tensile ratio and percent elongation are helpful when assessing sheet metal formability, for most steels it is the n-value along with steel thickness that determines the position of the forming limit curve (FLC) on the forming limit diagram (FLD). The n-value, therefore, is the mechanical property that one should always analyze when global formability concerns exist. That is also why the n-value is one of the key material related inputs used in virtual forming simulations.

Work hardening of sheet steels is commonly determined through the Holloman power law equation:

where

σ is the true flow stress (the strength at the current level of strain),

K is a constant known as the Strength Coefficient, defined as the true strength at a true strain of 1,

ε is the applied strain in true strain units, and

n is the work hardening exponent

Rearranging this equation with some knowledge of advanced algebra shows that n-value is mathematically defined as the slope of the true stress – true strain curve. This calculated slope – and therefore the n-value – is affected by the strain range over which it is calculated. Typically, the selected range starts at 10% elongation at the lower end to the lesser of uniform elongation or 20% elongation as the upper end. This approach works well when n-value does not change with deformation, which is the case with mild steels and conventional high strength steels.

Conversely, many Advanced High-Strength Steel (AHSS) grades have n-values that change as a function of applied strain. For example, Figure 2 compares the instantaneous n-value of DP 350/600 and TRIP 350/600 against a conventional HSLA350/450 grade. The DP steel has a higher n-value at lower strain levels, then drops to a range similar to the conventional HSLA grade after about 7% to 8% strain. The actual strain gradient on parts produced from these two steels will be different due to this initial higher work hardening rate of the dual phase steel: higher n-value minimizes strain localization.

Figure 2: Instantaneous n-values versus strain for DP 350/600, TRIP 350/600 and HSLA 350/450 steels.K-1

As a result of this unique characteristic of certain AHSS grades with respect to n-value, many steel specifications for these grades have two n-value requirements: the conventional minimum n-value determined from 10% strain to the end of uniform elongation, and a second requirement of greater n-value determined using a 4% to 6% strain range.

Plots of n-value against strain define instantaneous n-values, and are helpful in characterizing the stretchability of these newer steels. Work hardening also plays an important role in determining the amount of total stretchability as measured by various deformation limits like Forming Limit Curves.

Higher n-value at lower strains is a characteristic of Dual Phase (DP) steels and TRIP steels. DP steels exhibit the greatest initial work hardening rate at strains below 8%. Whereas DP steels perform well under global formability conditions, TRIP steels offer additional advantages derived from a unique, multiphase microstructure that also adds retained austenite and bainite to the DP microstructure. During deformation, the retained austenite is transformed into martensite which increases strength through the TRIP effect. This transformation continues with additional deformation as long as there is sufficient retained austenite, allowing TRIP steel to maintain very high n-value of 0.23 to 0.25 throughout the entire deformation process (Figure 2). This characteristic allows for the forming of more complex geometries, potentially at reduced thickness achieving mass reduction. After the part is formed, additional retained austenite remaining in the microstructure can subsequently transform into martensite in the event of a crash, making TRIP steels a good candidate for parts in crush zones on a vehicle.

Necking failure is related to global formability limitations, where the n-value plays an important role in the amount of allowable deformation at failure. Mild steels and conventional higher strength steels, such as HSLA grades, have an n-value which stays relatively constant with deformation. The n-value is strongly related to the yield strength of the conventional steels (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Experimental relationship between n-value and engineering yield stress for a wide range of mild and conventional HSS types and grades.K-2

N-value influences two specific modes of stretch forming:

- Increasing n-value suppresses the highly localized deformation found in strain gradients (Figure 1).

A stress concentration created by character lines, embossments, or other small features can trigger a strain gradient. Usually formed in the plane strain mode, the major (peak) strain can climb rapidly as the thickness of the steel within the gradient becomes thinner. This peak strain can increase more rapidly than the general deformation in the stamping, causing failure early in the press stroke. Prior to failure, the gradient has increased sensitivity to variations in process inputs. The change in peak strains causes variations in elastic stresses, which can cause dimensional variations in the stamping. The corresponding thinning at the gradient site can reduce corrosion life, fatigue life, crash management and stiffness. As the gradient begins to form, low n-value metal within the gradient undergoes less work hardening, accelerating the peak strain growth within the gradient – leading to early failure. In contrast, higher n-values create greater work hardening, thereby keeping the peak strain low and well below the forming limits. This allows the stamping to reach completion.

- The n-value determines the allowable biaxial stretch within the stamping as defined by the forming limit curve (FLC).

The traditional n-value measurements over the strain range of 10% – 20% would show no difference between the DP 350/600 and HSLA 350/450 steels in Figure 2. The approximately constant n-value plateau extending beyond the 10% strain range provides the terminal or high strain n-value of approximately 0.17. This terminal n-value is a significant input in determining the maximum allowable strain in stretching as defined by the forming limit curve. Experimental FLC curves (Figure 4) for the two steels show this overlap.

Figure 4: Experimentally determined Forming Limit Curves for mils steel, HSLA 350/450, and DP 350/600, each with a thickness of 1.2mm.K-1

Whereas the terminal n-value for DP 350/600 and HSLA 350/450 are both around 0.17, the terminal n-value for TRIP 350/600 is approximately 0.23 – which is comparable to values for deep drawing steels (DDS). This is not to say that TRIP steels and DDS grades necessarily have similar Forming Limit Curves. The terminal n-value of TRIP grades depends strongly on the different chemistries and processing routes used by different steelmakers. In addition, the terminal n-value is a function of the strain history of the stamping that influences the transformation of retained austenite to martensite. Since different locations in a stamping follow different strain paths with varying amounts of deformation, the terminal n-value for TRIP steel could vary with both part design and location within the part. The modified microstructures of the AHSS allow different property relationships to tailor each steel type and grade to specific application needs.

Methods to calculate n-value are described in Citations A-43, I-14, J-13.

![Uniform Elongation]()

Mechanical Properties

Necking: Diffuse Neck and Local Neck

A tensile bar increases in length as it is pulled, with a concurrent reduction in width and thickness. The cross section is rectangular in shape through uniform elongation. After uniform elongation, however, strains concentrate in the reduced section of the tensile test sample, resulting in a non-uniform section of reduced width. This region is known as a diffuse neck. The diffuse neck further accentuates and accelerates the cross-section reduction, leading to a concentration of strains within this region.

A local neck is a narrow band in the sheet metal part that is thinner than its surroundings (Figure 1). This local or through-thickness neck occurs shortly before the traditional fracture of the specimen. When the local neck begins, deformation stops in the remainder of the stamping. In a tensile bar, no deformation occurs along the width of the neck – only increased elongation and thinning. A local neck prevents a deeper section from being formed and serves as a crack initiation site. Additional loading, including fatigue loading during the life of the part, may cause a neck to progress to fracture (Figure 2). The strains resulting in a local neck are defined by the Forming Limit Curve, or FLC.

Figure 1: A local neck prevents forming a deeper section and serves as a crack initiation site.

Figure 2: Necking and fracture on a sample formed with a hemispherical dome.S-57

Traditional methods of detecting the onset of necking include tactile or visible sensing of the groove of the neck. Researchers are focusing on the use of non-contact approaches to define a neck. ISO 12004-2 calls for a polynomial fit of data outside the neck, but results from this method are a function of the order of the polynomial as well as the geometry of the tooling and the blank.

Using Digital Image Correlation allows for the detection in curvature evolution in the area that subsequently develops into a neck. The signature is detected for the many types of AHSS grades tested as well as other sheet metals, and correlates well with other methods. Citation S-57 presents an overview of the technique, with greater detail covered in Citations M-19 and S-58. Using the surface data geometry as measured by DIC to detect the true onset of necking enables better and more efficient use of AHSS grades through more reliable knowledge of their actual limits.

![Uniform Elongation]()

Mechanical Properties

Engineering stress-strain units are based on the starting dimensions of the tensile test sample: Engineering stress is the load divided by the starting cross-sectional area, and engineering strain is the change in length relative to the starting gauge length (2 inches, 50mm, or 80mm for ASTM [ISO I], JIS [ISO III], or DIN [ISO II] tensile test samples, respectively.)

Metals get stronger with deformation through a process known as strain hardening or work hardening. This is represented on the stress strain curve by the parabolic shaped section after yielding.

Concurrent with the strengthening as the tensile test sample elongates is the reduction in the width and thickness of the test sample. This reduction is necessary to maintain consistency of volume of the test sample.

Initially the positive influence of the strengthening from work hardening is greater than the negative influence of the reduced cross-section, so the stress-strain curve has a positive slope. As the influence of the cross-section reduction begins to overpower the strengthening increase, the stress-strain curve slope approaches zero.

When the slope is zero, the maximum is reached on the vertical axis of strength. This point is known as the ultimate tensile strength, or simply the tensile strength. The strain at which this occurs is known as uniform elongation.

Strain concentration after uniform elongation results in the formation of diffuse necks and local necks and ultimately fracture.

Figure 1: Tensile Strength is the Strength at the Apex of the Engineering Stress – Engineering Strain Curve.