Testing and Characterization

topofpage

The ISO 16630 Hole Expansion Test and the VDA238-100 bend test are among the few standardized tests to characterize local formability, the term which describes when part and process design, in addition to sheet metal properties like strength and elongation, influence the amount of deformation the metal can undergo prior to failure.

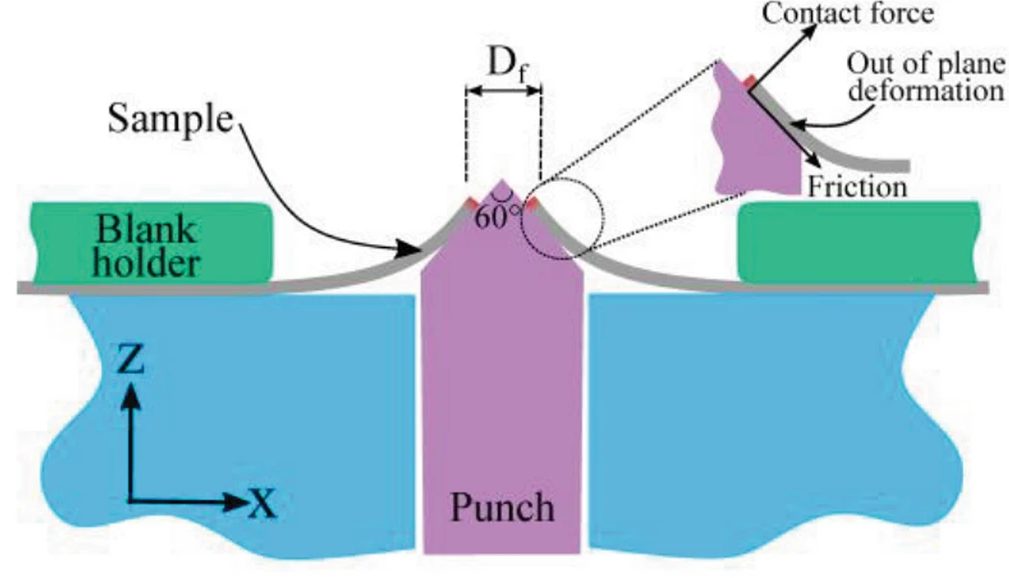

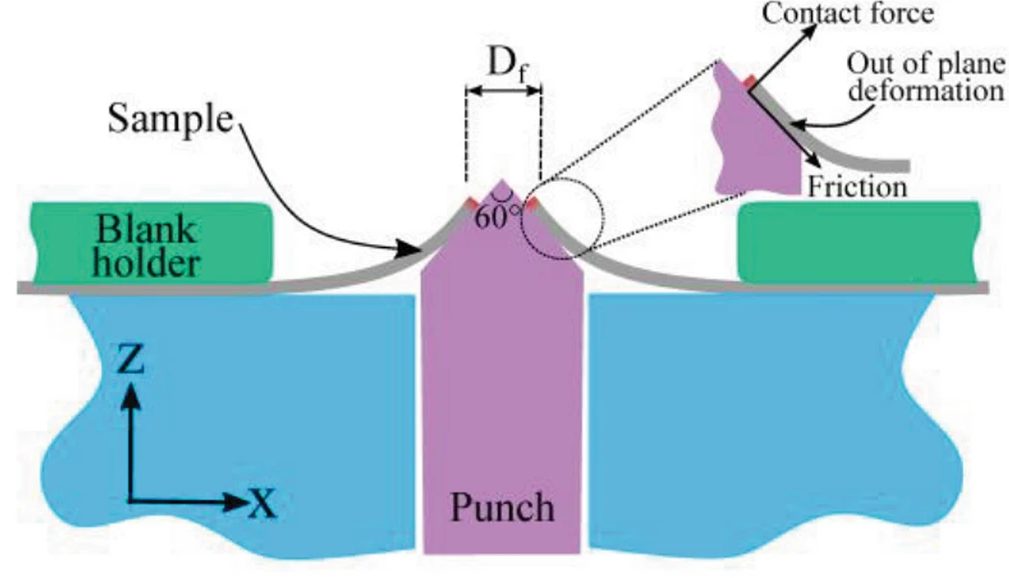

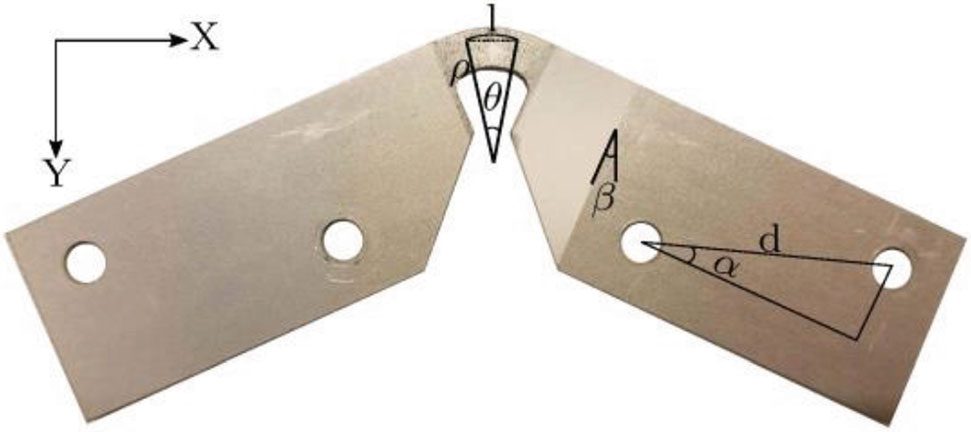

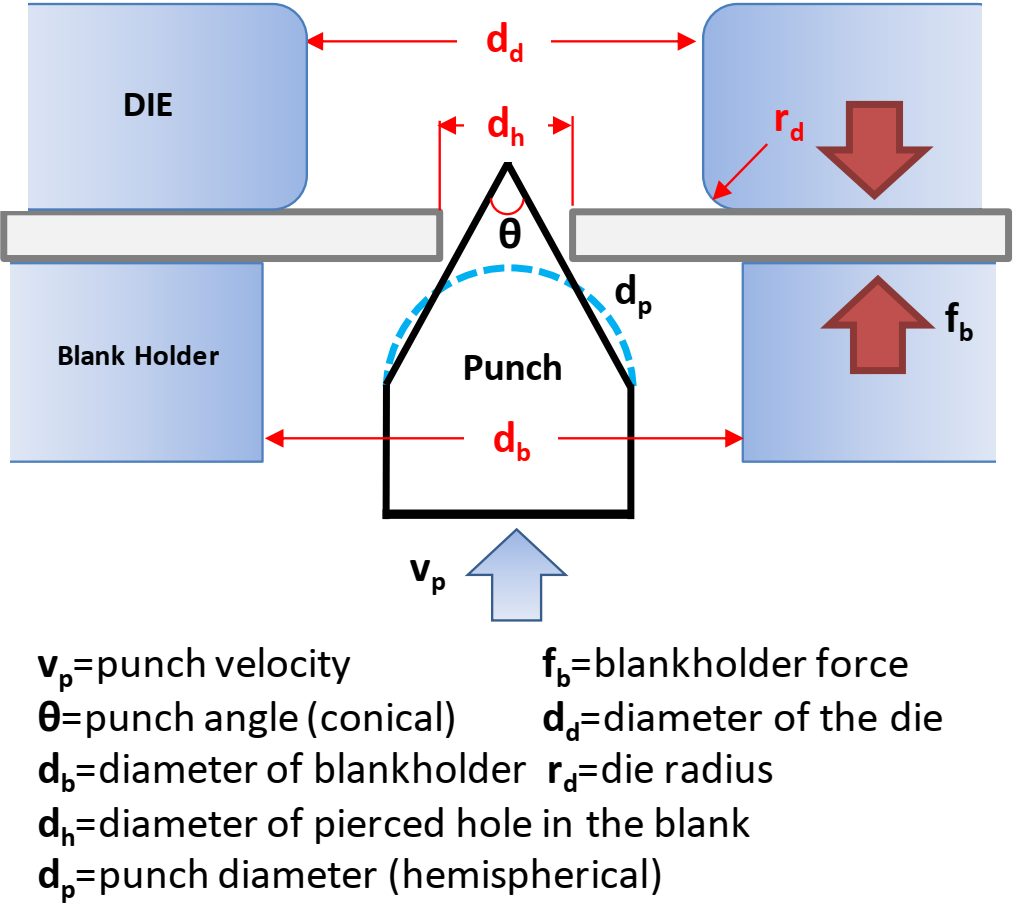

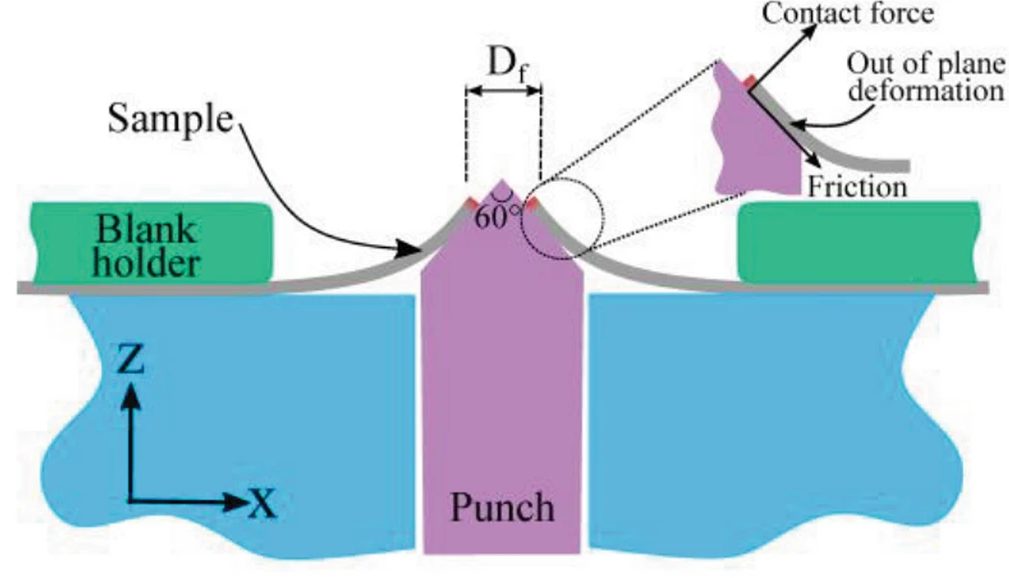

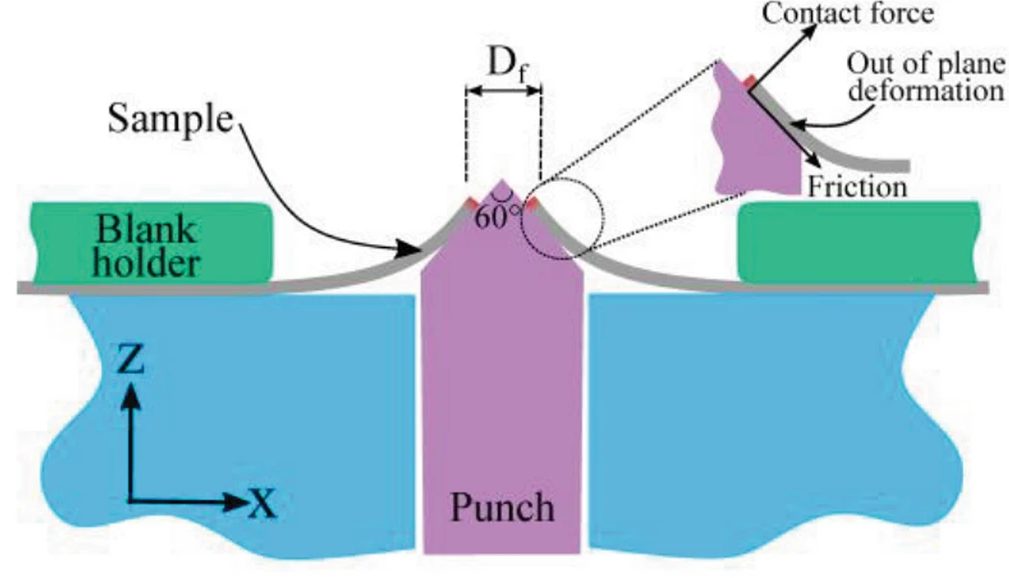

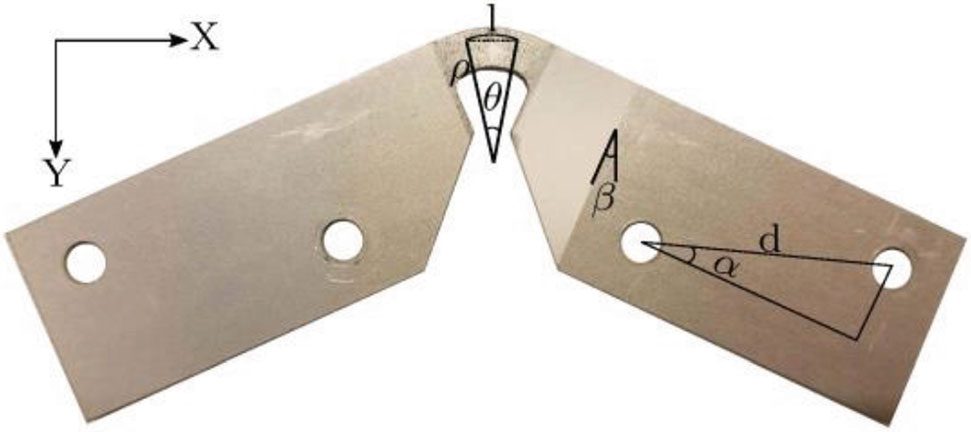

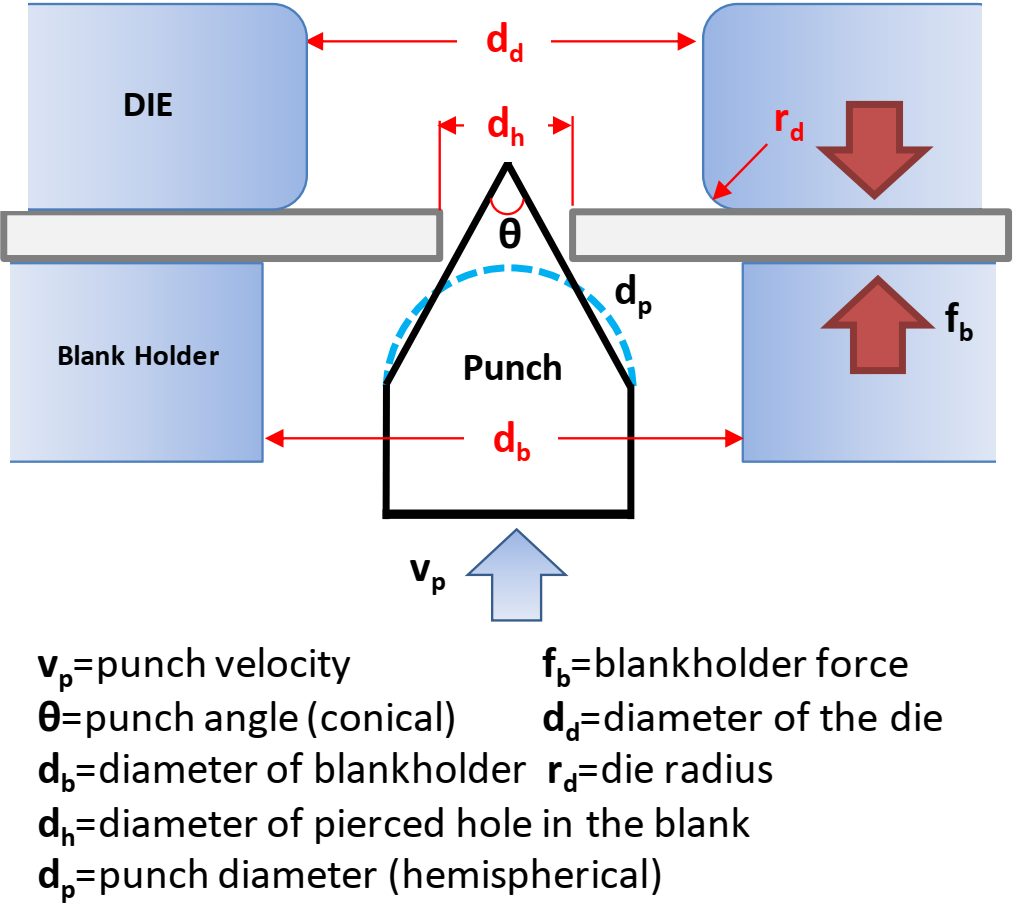

As schematically shown in Figure 1, the stress state at the edge of the hole expansion test specimen is influenced by friction, contact forces, and out-of-plane deformation, and therefore the hole expansion ratio as determined by ISO 16630 is not solely a material characteristic.

Figure 1: Parameters influencing stress state at edge of hole expansion test specimen.K-68

Researchers have developed alternate tests to further investigate process parameters and more clearly understand and optimize non-steel related variables. Also important is the investigation of different strain states from the ones seen in the hole expansion and bending tests. Comparisons of the stretched or bent edge performance evaluating different process parameters using the same material help to better define optimum process parameters. Repeating the testing with different AHSS grades confirms if similar trends exist across different microstructures and strengths. Standardization of these alternate tests has not yet occurred, so use caution when comparing specific values from different studies.

Hole Tension Test (In-Plane Deformation)

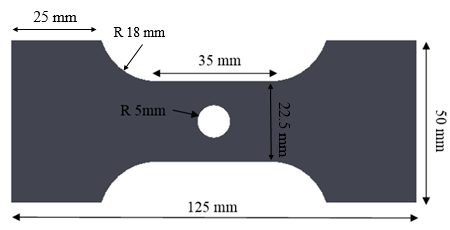

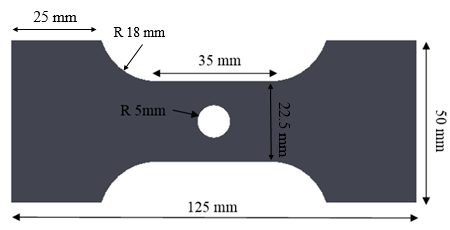

Microstructural damage in the shear affected zone reduces edge ductility. Damage has been evaluated with a modified tensile dogbone containing a central hole prepared by shearing or reaming, as shown in Figure 2. In contrast with a hole expansion test using a conical punch, the researchers described this as a Hole Tension test, which determines failure strain as a function of grade and edge preparation.

Figure 2: Hole Tension Test Specimen GeometryP-12

Edge Tension Test (In-Plane Deformation)

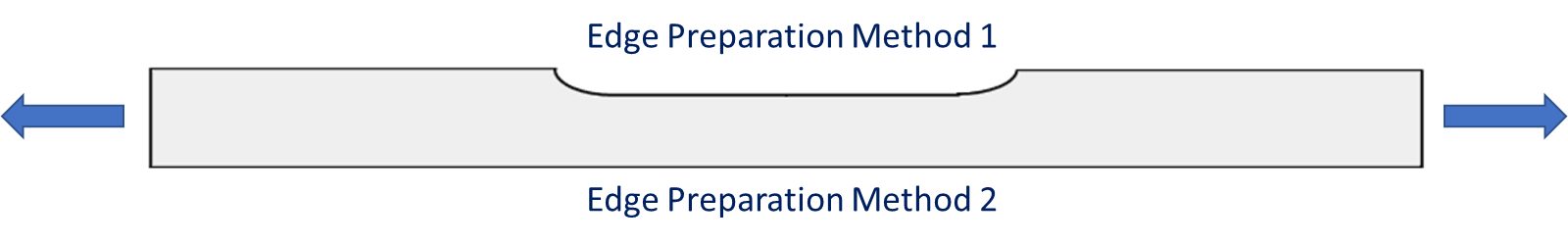

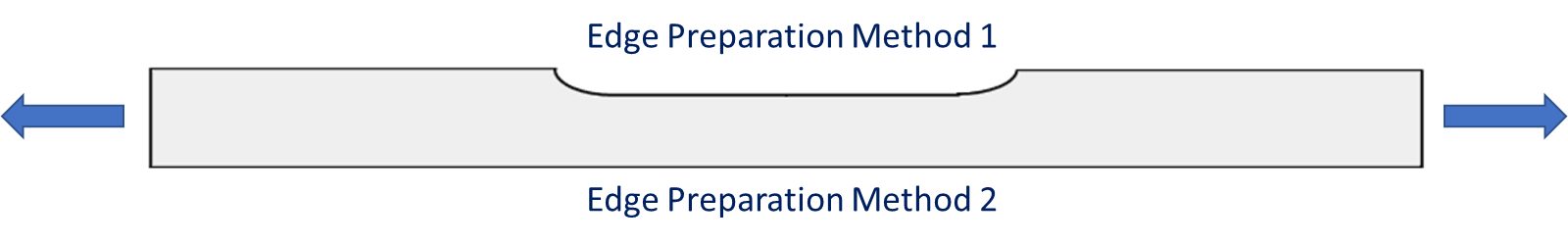

A two-dimensional (2-D) edge tension test, also called Half-A-Dogbone test, also evaluates edge stretchability. There are multiple versions of this type of test, but they all are based on the same concept. Like a standard tensile test, the 2-D edge tension test pulls a steel specimen in tension until failure. Unlike a standard tensile test where both sides of the tensile specimen are milled into a “dog bone”, the 2D tension test uses half of a dogbone with different preparation methods for the straight edge and the edge containing the reduced section (Figure 3). The chosen preparation method for each face is a function of the parameter being investigated (ductility, strain, burr, and shear affected zone for example). Potential edge preparation methods include laser cutting, EDM, water jet cutting, milling, slitting or mechanical cutting at various trim clearances, shear angles, rake angles or with different die materials.

Figure 3: 2-D Edge Tension Test Sample. Note the edges are prepared differently based on the targeted property evaluated.

The hole expansion test is prone to scatter in the results. Many replicates are usually tested to improve the robustness of any conclusions. In addition, the test averages the strains over the entire circumference, and as such is lower than the peak strain immediately surrounding the location of crack initiation.

The Sheared Edge Tensile test (SET)W-25 has many merits: it does not require many samples, sample preparation is relatively easy, and the test itself can be performed on a regular tensile test machine. However, the test itself can be complicated to execute, partially because it requires stopping the test immediately after a load drop of 0.5% to 4% from peak load. Full separation of the specimen after failure is to be avoided since it can cause substantial distortion of the cross section along the failure.

This test was modified to eliminate the need to monitor and control based on load drop by using non-contact optical strain measurements facilitated by DIC (digital image correlation), creating what is termed the Sheared Edge Tensile – Improved test (SETi).A-92

A benefit of the use of DIC with SETi is that local peak strains can be captured, allowing for determination of critical strain measurements that can be fed into forming simulations.

More information about SETi can be found in Citations A-92 and A-93.

Side Bending Test (In-Plane Deformation)

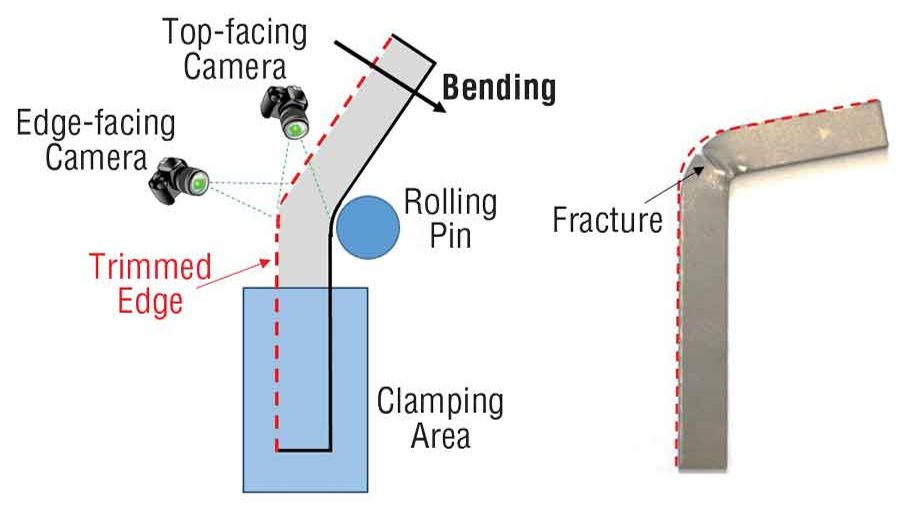

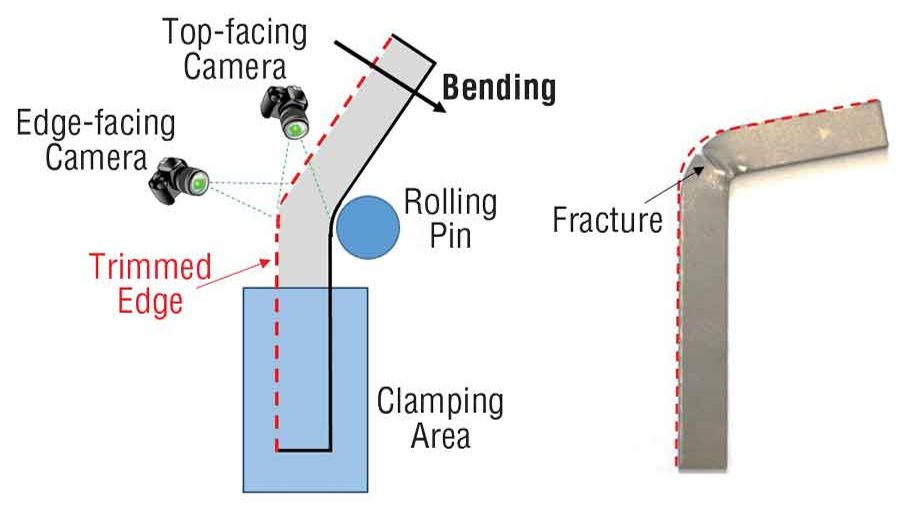

Instead of a dogbone or half-dogbone, some studies use a rectangular strip without a reduced section. Bending performance can be evaluated with a rectangular strip having one finished edge and one trimmed edge while preventing out-of-plane buckling, as shown in Figure 4.G-7

Figure 4: The side-bending test expands a trimmed edge over a rolling pin until detection of the first edge crack.G-7

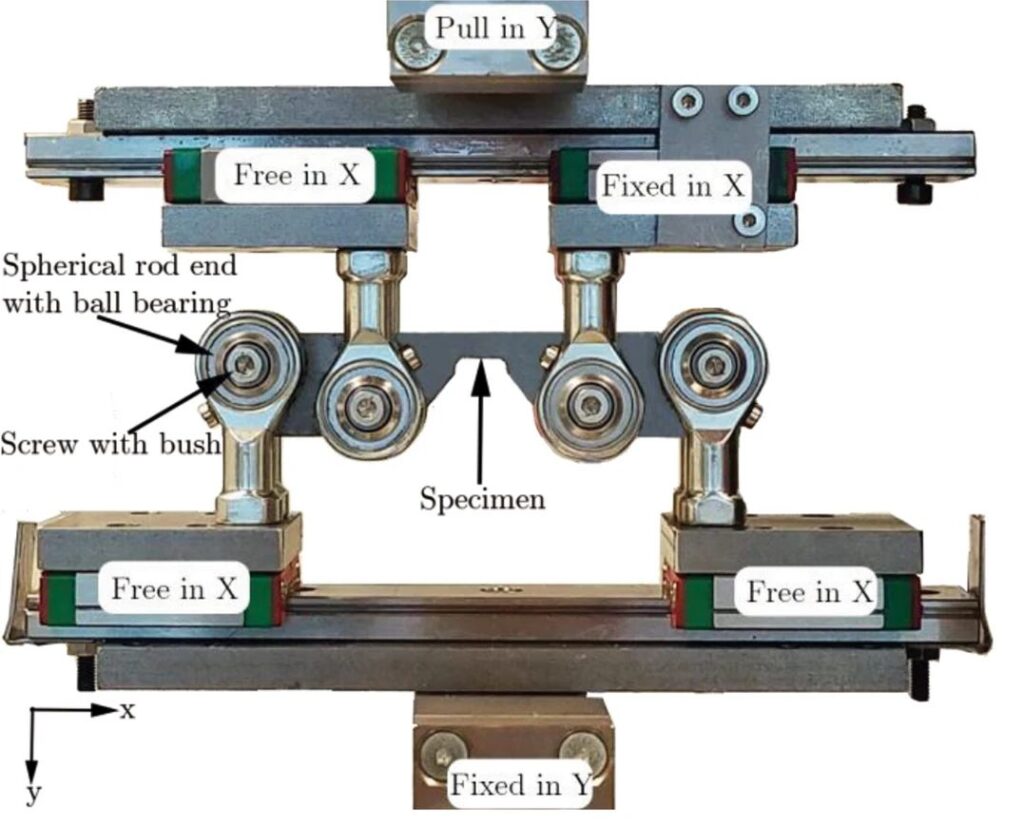

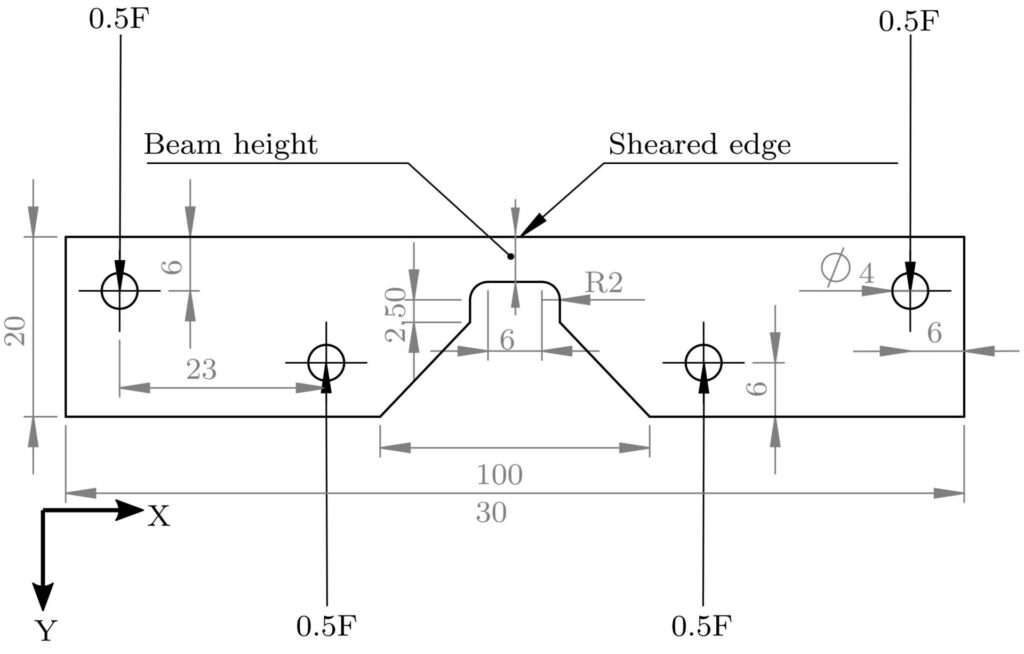

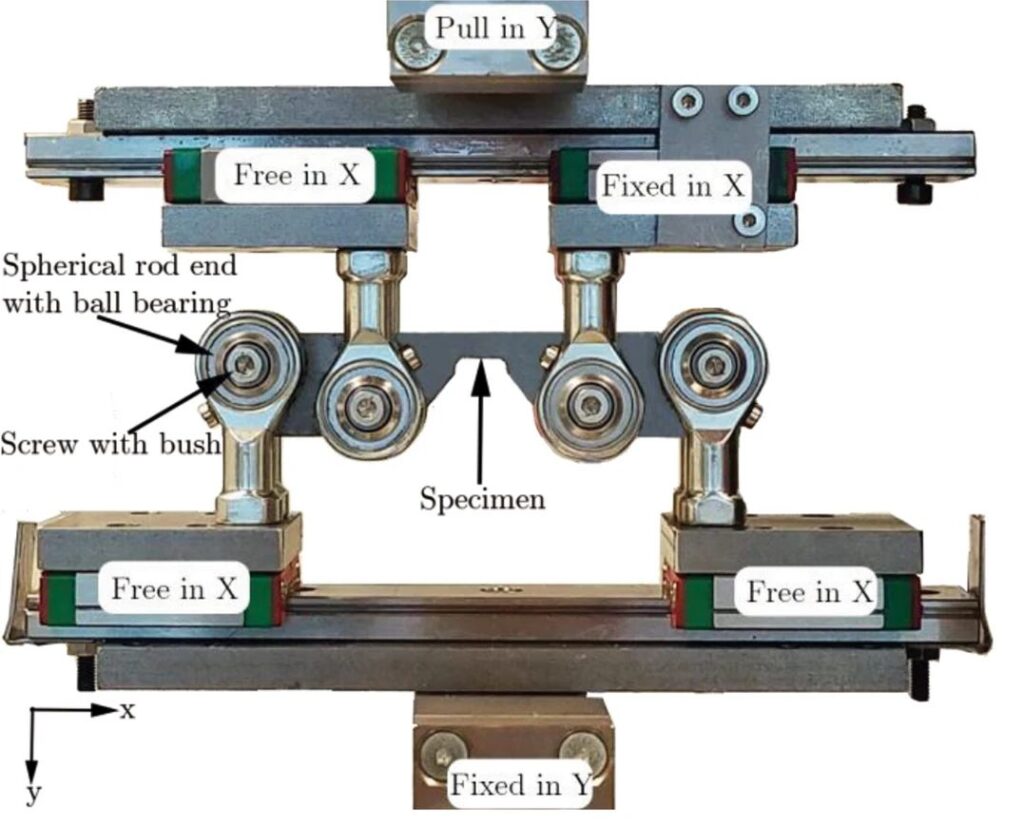

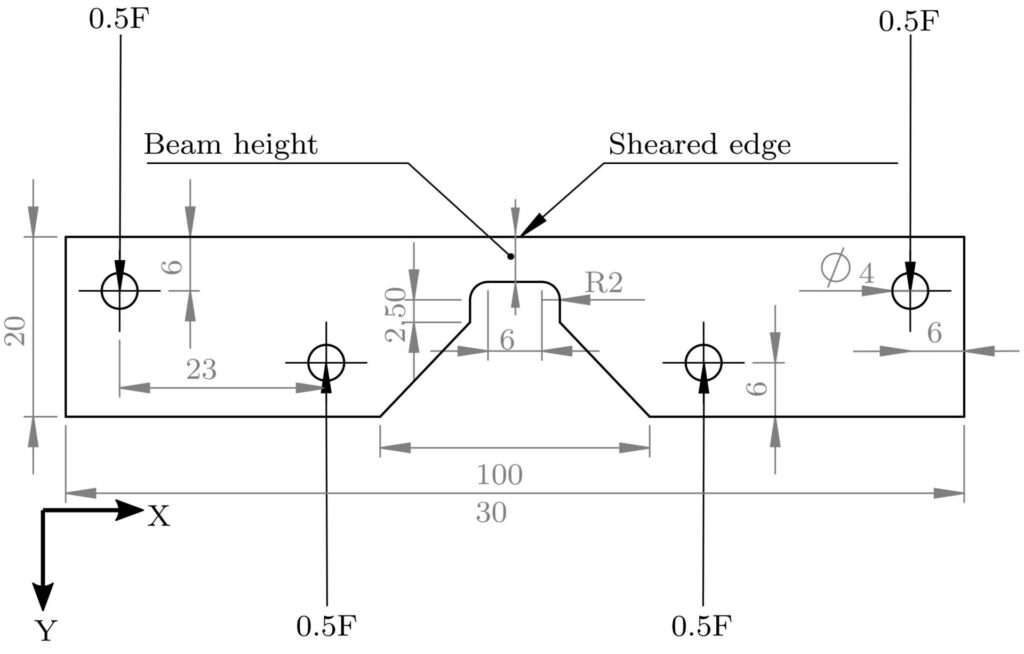

Another type of in-plane side bending test is described in Citation K-68. The set-up shown in Figure 5 delays necking, allowing for determination of the hardening curve above uniform elongation. A key addition to the fixture is the anti-bucking mechanism. Unlike a standard hole expansion test, there is no friction and contact stress on the edge. The strain gradient is controlled by changing the beam height of the sample (Figure 6). An indication of the measurable dimensions after deformation is seen in Figure 7.

Figure 5: In-plane bending test fixture.K-69

Figure 6: Sample geometry for in-plane bending test.K-69

Figure 7: Deformed sample after in-plane bending test.K-68

The in-plane bending test provides more details of fracture strain in a desired material orientation relative to the rolling direction compared with the axisymmetric hole expansion test. In the hole expansion test, the weakest direction determines the result due to inherent rotational symmetry in the test. With potential anisotropy in the martensite morphology found in DP steels, the ability to improve characterization in specific orientations may be useful.

The in-plane bending test was used to show a DP800 sheared edge parallel to the transverse direction has a lower fracture strain than a sheared edge parallel to the rolling direction. Furthermore, a sharper cutting tool improves edge ductility.K-68 All tests allowed for two weeks between cutting and testing; over that two week period edge fracture strain is influenced by the time between cutting and testing, but stabilizes after two weeks.A-91

This test also was used to explore void distribution and the uniformity of plastic deformation in sheared edges.K-70 This study shows that the blanking process creates an inhomogeneous void distribution in the thickness direction. As the deformation increases during the subsequent in-plane bending test, the micro-cracks initiate at the burr region and grow towards the rollover region. Once they entirely pass the thickness of the material, they grow further, away from the edge.

No voids are present in the relatively smoother rollover and burnish regions of the sheared edge, whereas the rougher fracture region and burr contain many voids. The majority of voids are a result of martensite cracking and separation of ferrite–martensite interfaces.

Overall, the initial void volume fraction inside the severely hardened layer of the as-cut edge plays a more critical role than roughness in edge ductility. Removing the volume from edge with high void density (in this case, 40 microns) is enough to significantly increase the edge ductility. It is not necessary to remove the complete shear-affected zone, which for this study is on the order of 500 microns.

Half-Specimen Dome Test (Out-of-Plane Deformation)

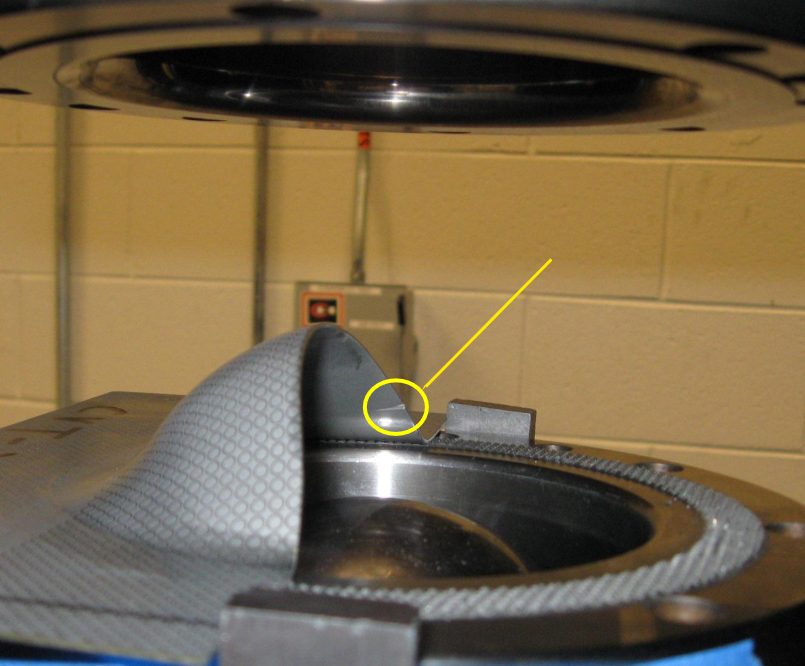

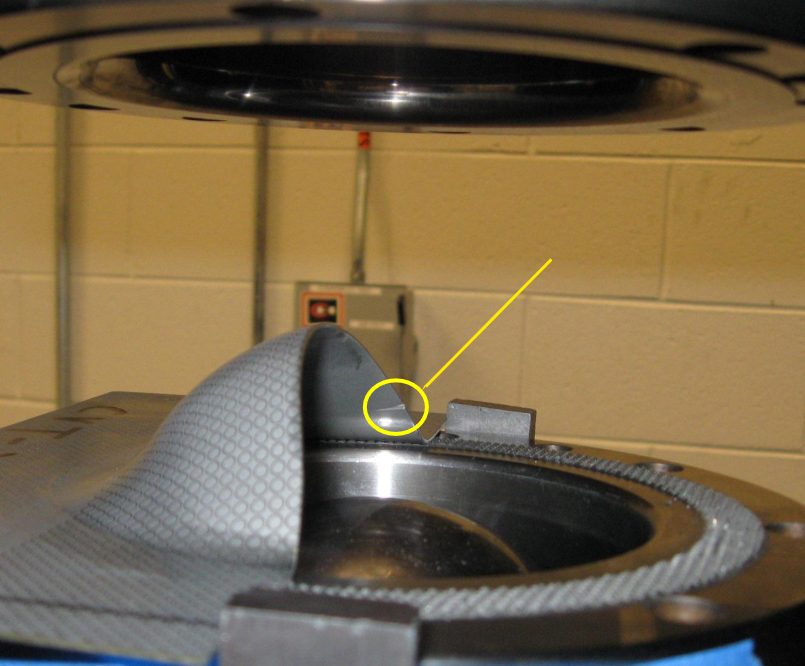

Deformation in these three tests occur in the plane of the sheet. Typical hole expansion tests, like production stampings, deform the sheet metal perpendicular to the plane of the sheet. However, hole expansion testing does not always give consistent test results. The half-specimen dome test (HSDT) also attempts to replicate this 3-dimensional forming mode (Figure 8), and appears to be more repeatable likely due to creating a straight cut rather than round hole.

In the HSDT, a rectangular blank is prepared with one edge having the preparation method of interest, like sheared with a certain clearance or laser cut or water-jet cut. The sample is then clamped with the edge to be evaluated over a hemispherical punch. The punch then strains the clamped sample creating a dome shape, with the test stopping with the first crack appears at the edge. Edge stretchability is quantified by measuring dome height or edge thinning or other characteristics.

Figure 8: Half-Specimen Dome Test sample. Arrow points to edge crack.S-12

Edge Flange Test (Out-of-Plane Deformation)

Flanging limits depend on the part contour, edge quality, and material properties. Non-optimal flange lengths – either too long or too short – will lead to fracture. Different tools can assess the influence of flange length, including the one shown in Figure 9 from Citation U-3.

Figure 9: Tool design to investigate flange length before fracture. Flange height: 40mm in left image, 20mm in right image.U-3

Physical tests using this tool show that optimizing sample orientation relative to the rolling direction leads to longer flange lengths before splitting.U-3 Figure 10 highlights the results from testing DP800.

Figure 10: Flange height limits as a function of orientation in DP800.U-3

Effect of Time on Edge Ductility

The time passed between cutting and deforming has a large influence on the test results.

Edge ductility test results are impacted by the amount of elapsed time between cutting and deforming. Citation A-91 documented this effect on two coils each of galvanized or bare dual phase steels having different chemistry that were evaluated with Hole Expansion Capacity (HEC), Sheared Edge Tensile – Improved (SETi), and BMW’s Kantenriss Empfindlichkeitstest (translated to edge crack sensitivity test, abbreviated as KRE) tests.

The difference between testing a few hours versus a few days after cutting can be a reduction of up to 10 HEC%, or a true strain of 0.1. Property values appear to be stable when tested within 4 hours after cutting or after 24 hours after cutting, at the high and low values, respectively. It was also found that this effect pertains only to zinc coated materials – no edge ductility reduction over time was found in bare steels.

A practical implication of this time effect is that a galvanized part formed in a coil-fed press line should have fewer problems with edge ductility than if blanks were prepared offline in advance, all other things being equal.

At least one automotive OEM recognizes this and puts timing restrictions on the hole expansion evaluation test procedure, stating that there must be a delay of “24 h ± 1 h at room temperature” after punching but before the hole expansion test begins to avoid the aging effect.

Making a second cut to remove the work hardened zone produced during the first cut, called shaving or pre-piercing, can improve the edge ductility. See the bottom of our page on shearing for more information. This practice may have the additional benefit of reducing or eliminating the time delay sensitivity associated with stretching of galvanized cut edges.

Although Citation A-91 evaluated only coated and uncoated DP steels, similar conclusions were drawn in another study covering dual phase (DP), complex phase (CP), and high strength low alloy (HSLA) grades,S-126 and another study covering DP steels of different strength levels.W-46

However, another studyC-44 observed a decrease in hole expansion capacity for galvanized complex phase steel, uncoated martensitic steel, and one galvanized dual phase grade. Yet the effect was absent in galvanized bake hardening (BH), uncoated transformation induced plasticity aided bainitic-ferritic (TBF), and another uncoated dual phase grade. A related studyC-45 concluded that the advanced high strength grades with good edge ductility were the most susceptible to a decrease in edge stretchability with aging.

Influence of Starting Dimension

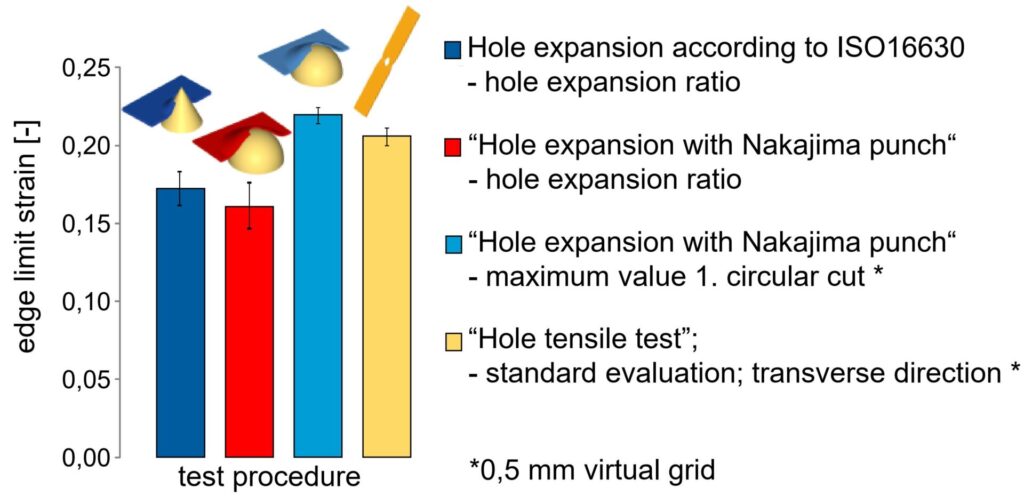

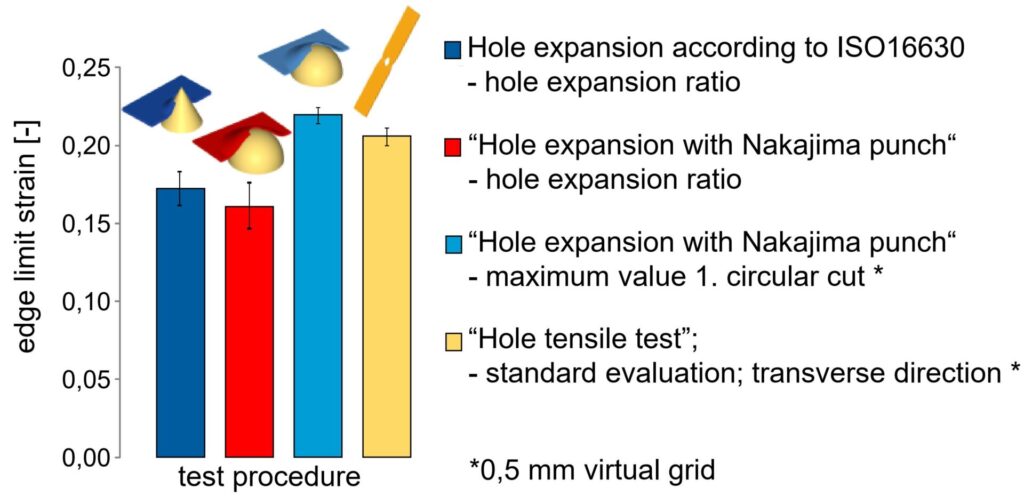

In addition to the time between edge creation and testing, the starting reference dimension of the analyzed region influences the results. Edge strains of samples from CR440Y780T-DP were evaluated using four tests: two with a relatively large strain reference length, and two associated with smaller strain reference lengths. It is found that the measured edge formability increases with a smaller strain reference length.S-127

This is similar to the effect seen in a comparison of A80 and A50 tensile bars, where A80 – having the longer reference length – is associated with lower elongation values than on an A50 bar of the same material.

The strain reference length in physical testing should correspond to the element size in associated forming simulation.

Figure 11: Limiting edge strains of the same material tested and evaluated differently. The red bar is from a conventional ISO 16630 test, except a dome was used to expand the hole instead of a conical punch. The lighter blue bar are the results from the same test, but a non-contact DIC method was used to measure the limiting strains instead of the change in hole diameter.S-127

Back to the Top

Testing and Characterization

The term local formability describes when part and process design, in addition to sheet metal properties like strength and elongation, influence the amount of deformation the metal can undergo prior to failure. Cutting, punching or other methods of obtaining a trimmed blank or an internal hole results in cracks, rough edges, work-hardening and other edge damage – all of which influences edge quality. The challenges of capturing all of the factors that influence edge quality makes the prediction of fracture severity and cut edge expansion very difficult and usually impossible. The many variables highlight the need for a standardized test method. However, restricted sample preparation and testing variables in these standards do not reflect the variety of conditions encountered in production environments. Use caution when comparing results generated under different conditions.

Hole Expansion Testing

The Hole Expansion test (HET) quantifies the edge stretching capability of a sheet metal grade having a specific edge condition. Higher values of the hole expansion ratio are associated with grades and forming methods more likely to have improved local formability characteristics.

Steel producers study hole expansion capacity to create new products with targeted edge stretching performance through modifications of chemistry, rolling and thermal practices. Product designers use the hole expansion test to determine if the chosen steel grade has the inherent forming characteristics to meet their targeted shape with their chosen forming system. If they are not compatible, the chosen grade must change or aspects of the forming process must change, or possibly both.

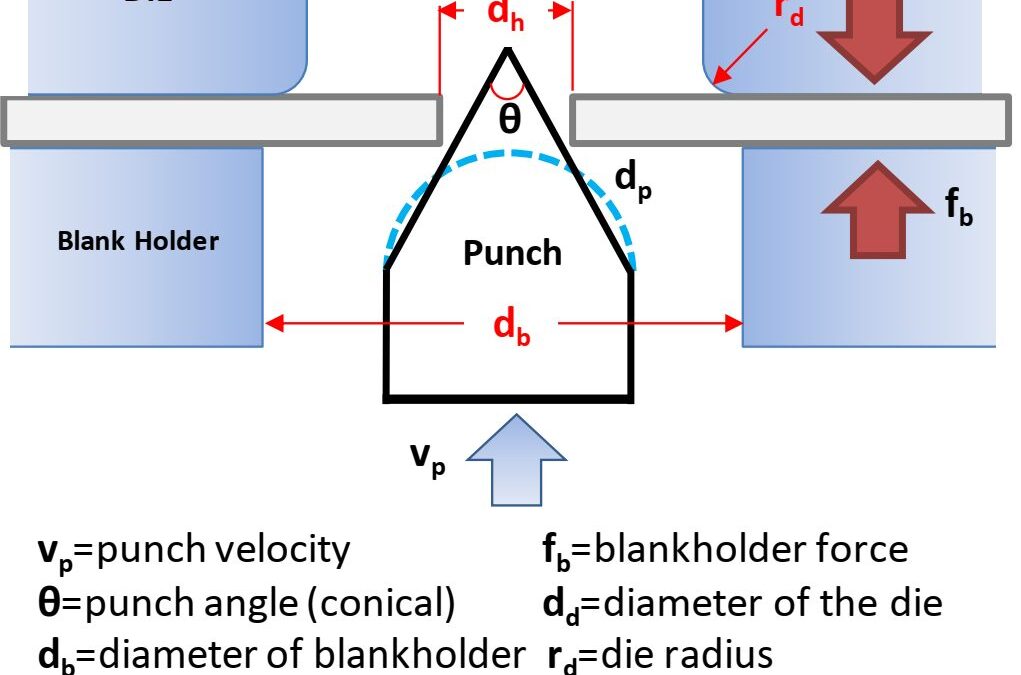

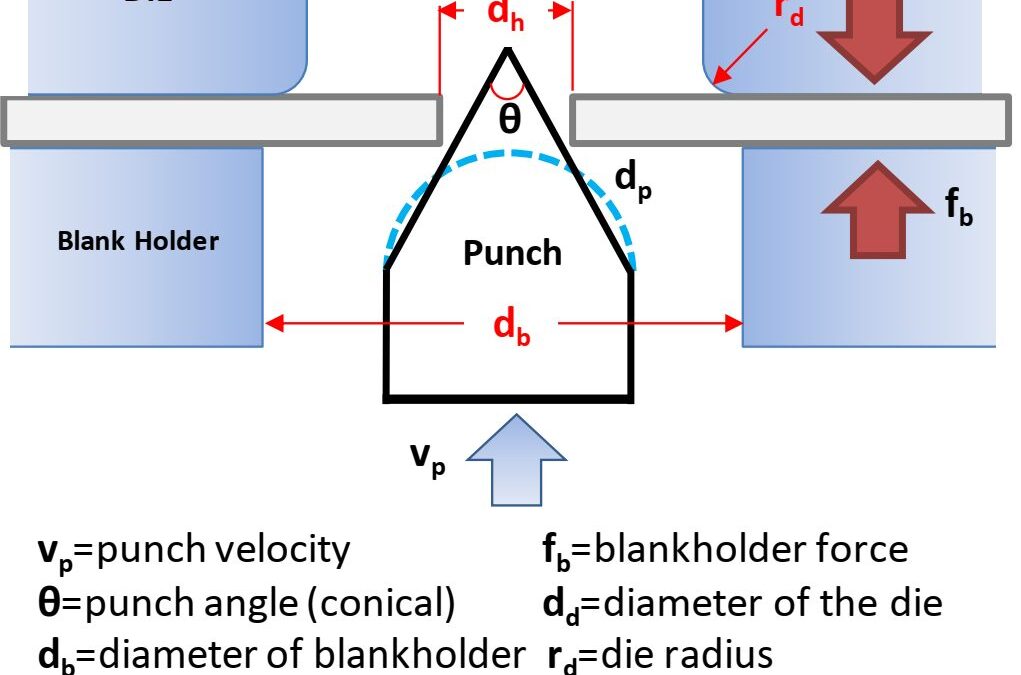

ISO 16630 is the primary standard used which describes the test method and constraints.I-9 Others, like JIS Z 2256J-6 are based on the ISO standard, with only minor differences, if any. This standard specifies use of a 10mm diameter hole created with a 12% clearance. The sample containing the hole is clamped in place, and a conical punch having a 60 degree apex angle expands that initial hole (Figure 1). The test stops after observation of a through-thickness crack or upon experiencing a load-drop exceeding a critical threshold (Figure 2). The hole expansion ratio (HER), also known as the Hole Expansion Capacity (HEC), is simply the percent expansion of the diameter of the initial hole, typically shown as the Greek letter lambda, λ.

Figure 1: Schematic of Hole Expansion Test.A-10

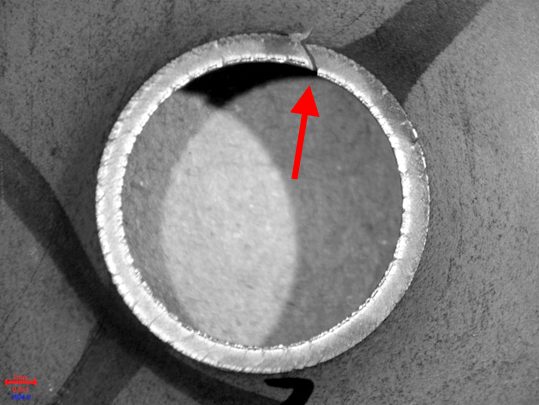

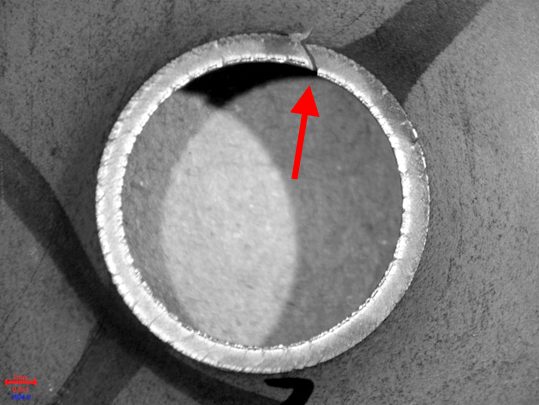

Figure 2: Expanded Edge at the end of a Hole Expansion Test performed using a conical punch. The arrow points to the through-thickness crack that ended the test.E-2

The sample preparation and testing requirements of ISO 16630 are well-defined for good reason. Factors known to influence the hole expansion ratio include:

Even with these rigorously defined procedures, the test results can be heavily influenced by specimen preparation technique, specific test parameters, and human subjectivity – in other words, poor gage R&R (repeatability and reproducibility). For example a group of European steel researchers reported “an unacceptably large difference between labs” with regard to hole expansion testing. They ultimately concluded that the “difference is too large for the method to be useful in practice”.

A-76

Testing sheet steels of different thicknesses in a laboratory setting requires having multiple punches and/or dies of different diameter to maintain a consistent clearance, which is based on a percentage of the sheet thickness tested.

In production, the punch-to-die clearance can change during the life of the part, both from tooling wear as well as press misalignment. There is the additional risk that clearance can vary around the perimeter of the cut section, leading to inconsistent performance. Increasing sheet metal strength magnifies this issue.

The method used to create the free edge influences the edge quality. Improved edge quality and reduced mechanical work hardening of the edge is achieved by laser cutting, EDM cutting, water jet cutting, or fine blanking processes, and will typically improve the hole expansion ratio. Trim steel clearances, shear angles, tool steel types, and sharpness also impact hole expansion test results.

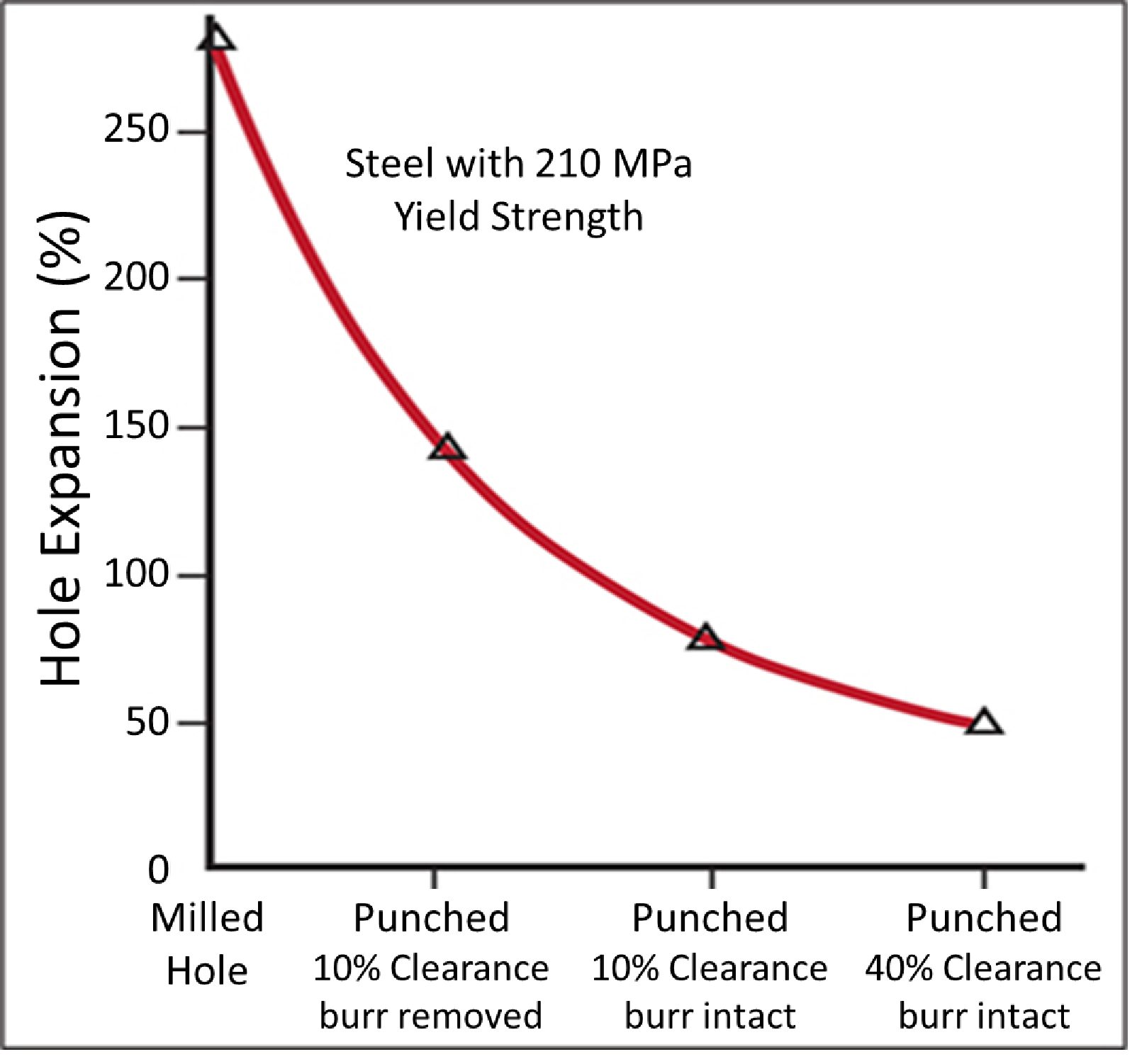

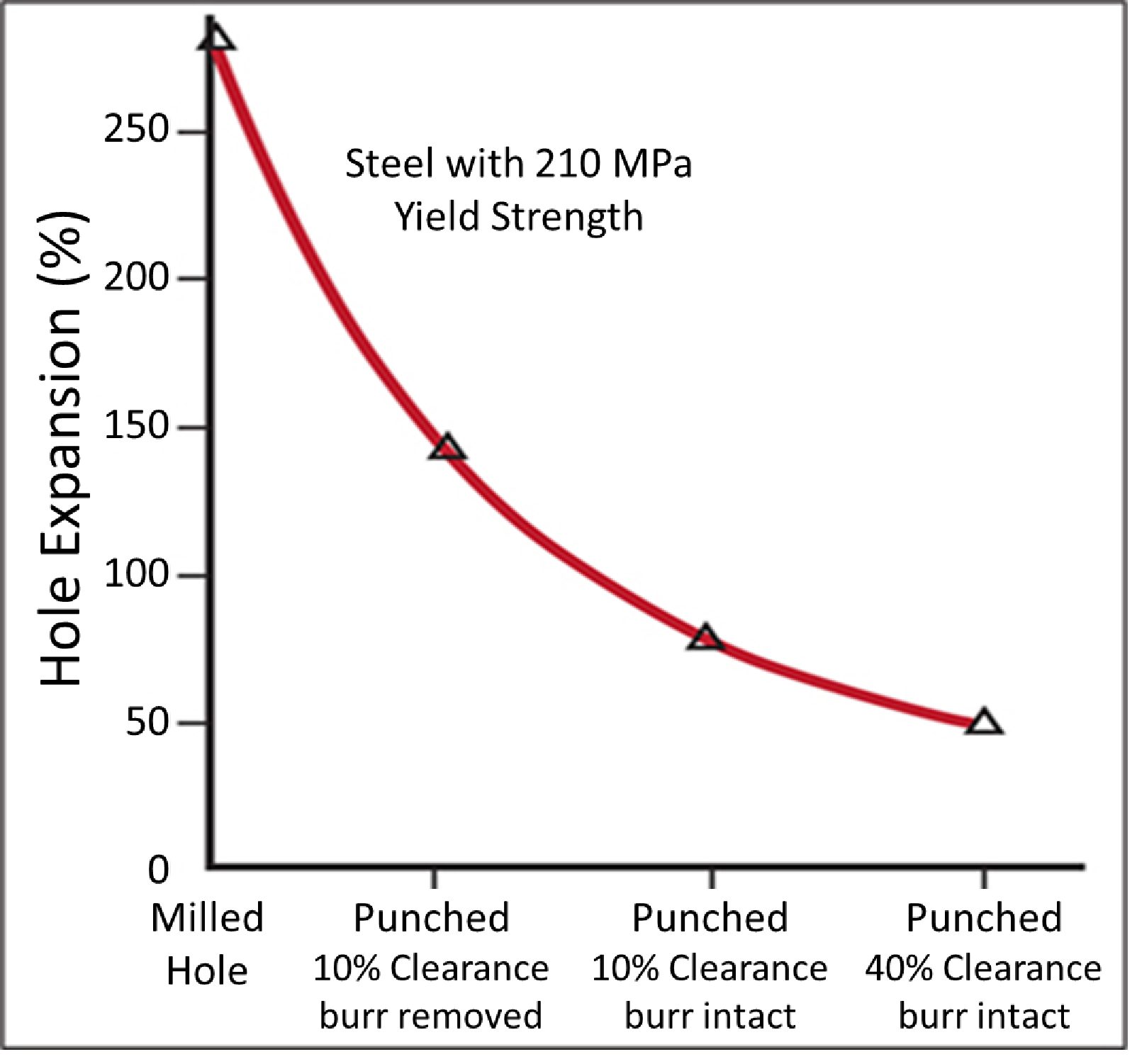

In the example shown in Figure 3, the hole expansion ratio is reduced from 280% for a milled or water jet edge down to 80% for a traditional cut edge. If clearances further increase – which could happen without proper tooling maintenance over the life of the part – the ability to expand a cut edge further decreases.

Figure 3: Hole Expansion Capacity Decreased as Edge Quality Decreases. (Based on data from Citation H-1.)

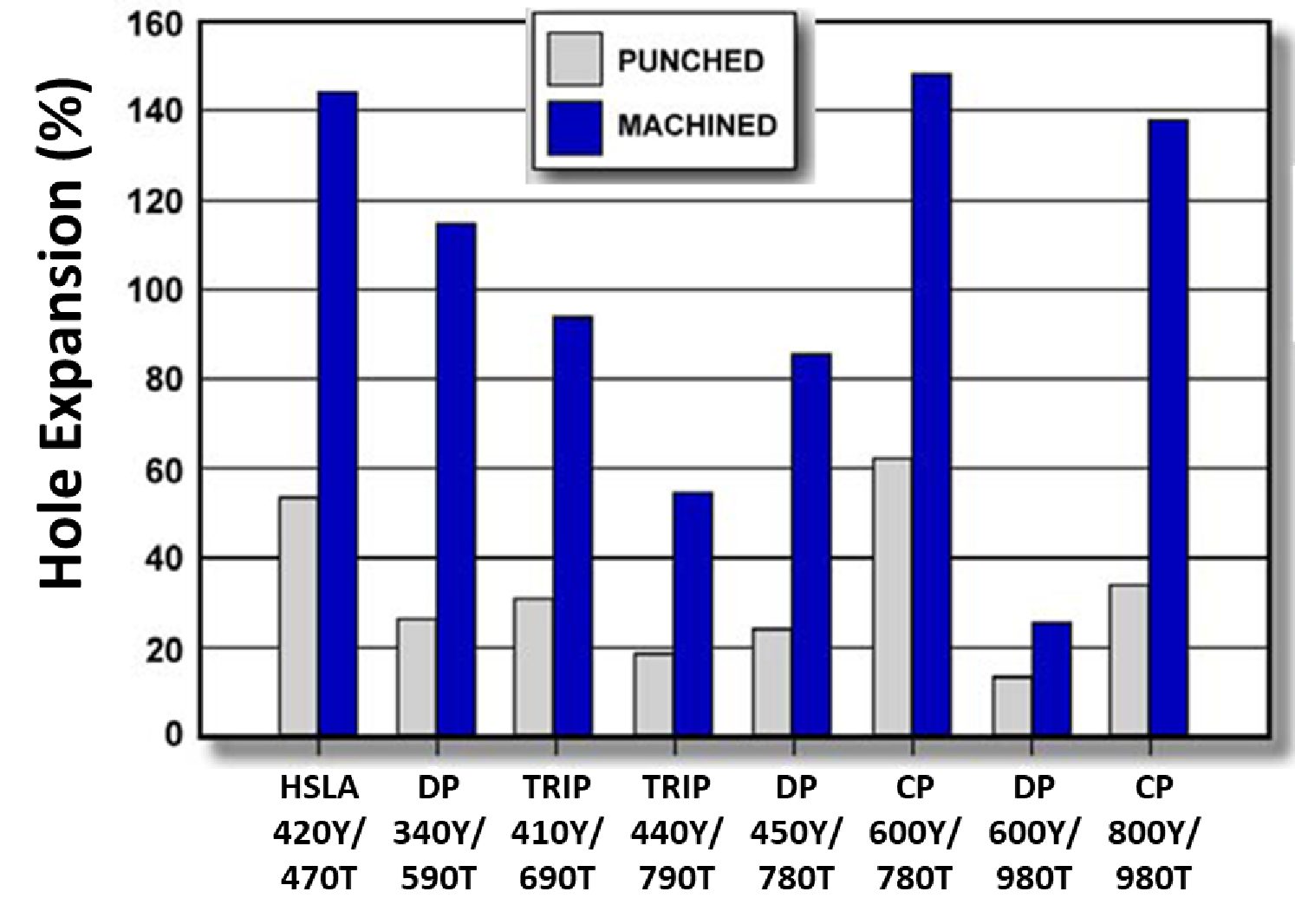

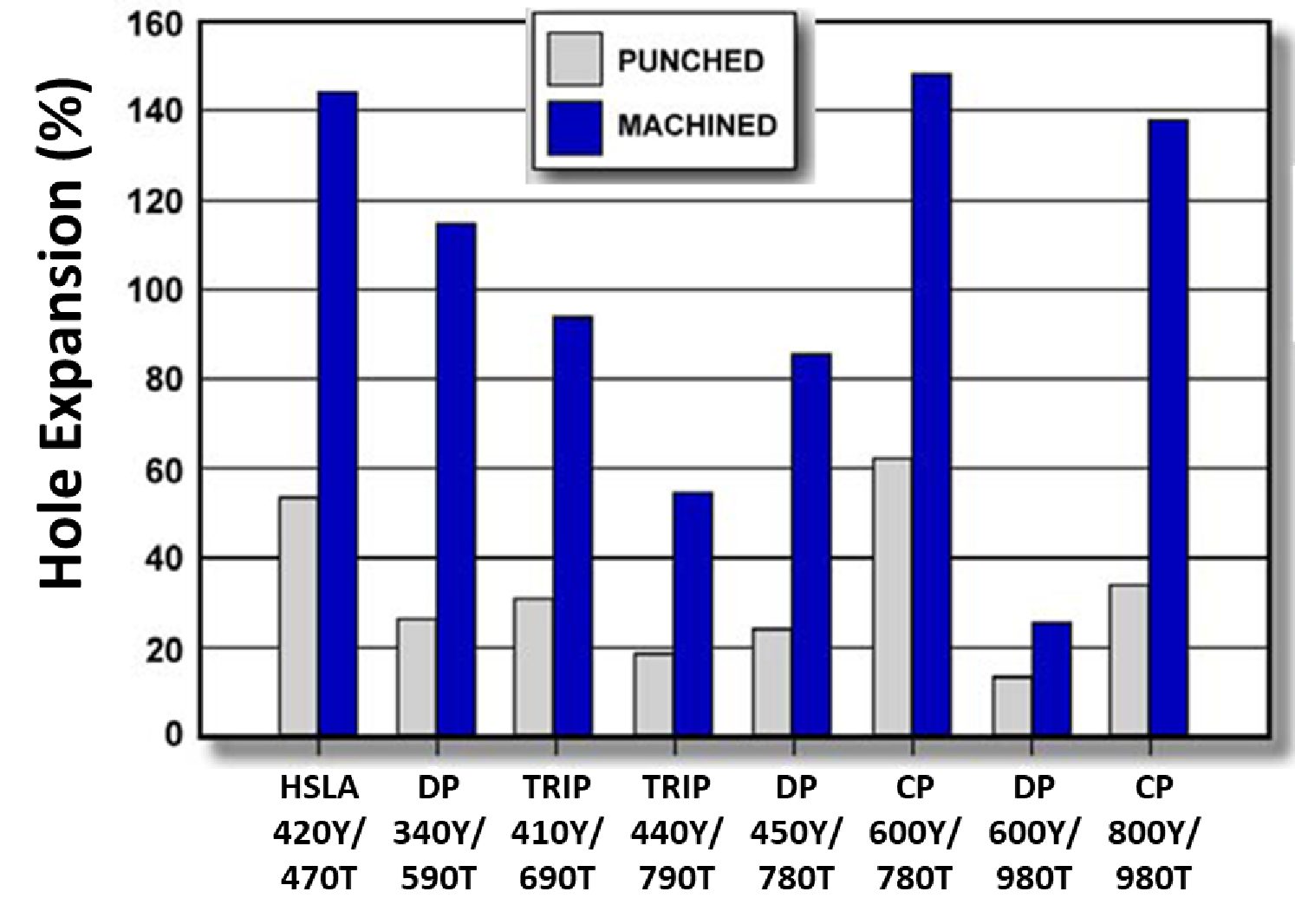

Figure 4 highlights the effect of punched vs machined holes, showing the edge damage from punching lowers the hole expansion capability. This edge damage becomes a key component of what is known as the Shear Affected Zone, or SAZ. DP steels and TRIP steels have a large hardness difference between the constituent phases, and therefore are associated with lower hole expansion ratios than HSLA and CP steels, where the phases are of more similar hardness. The influence of the metallurgical phase hardness difference is explored here. Detailed studies of sheared edge stretchability as a function of clearance, edge preparation, and grade are shown in Citations K-6 and K-10.

Figure 4: Hole expansion test results comparing punched and machined holes showing effect of damage to edge stretchability. (Based on data from Citation V-1.)

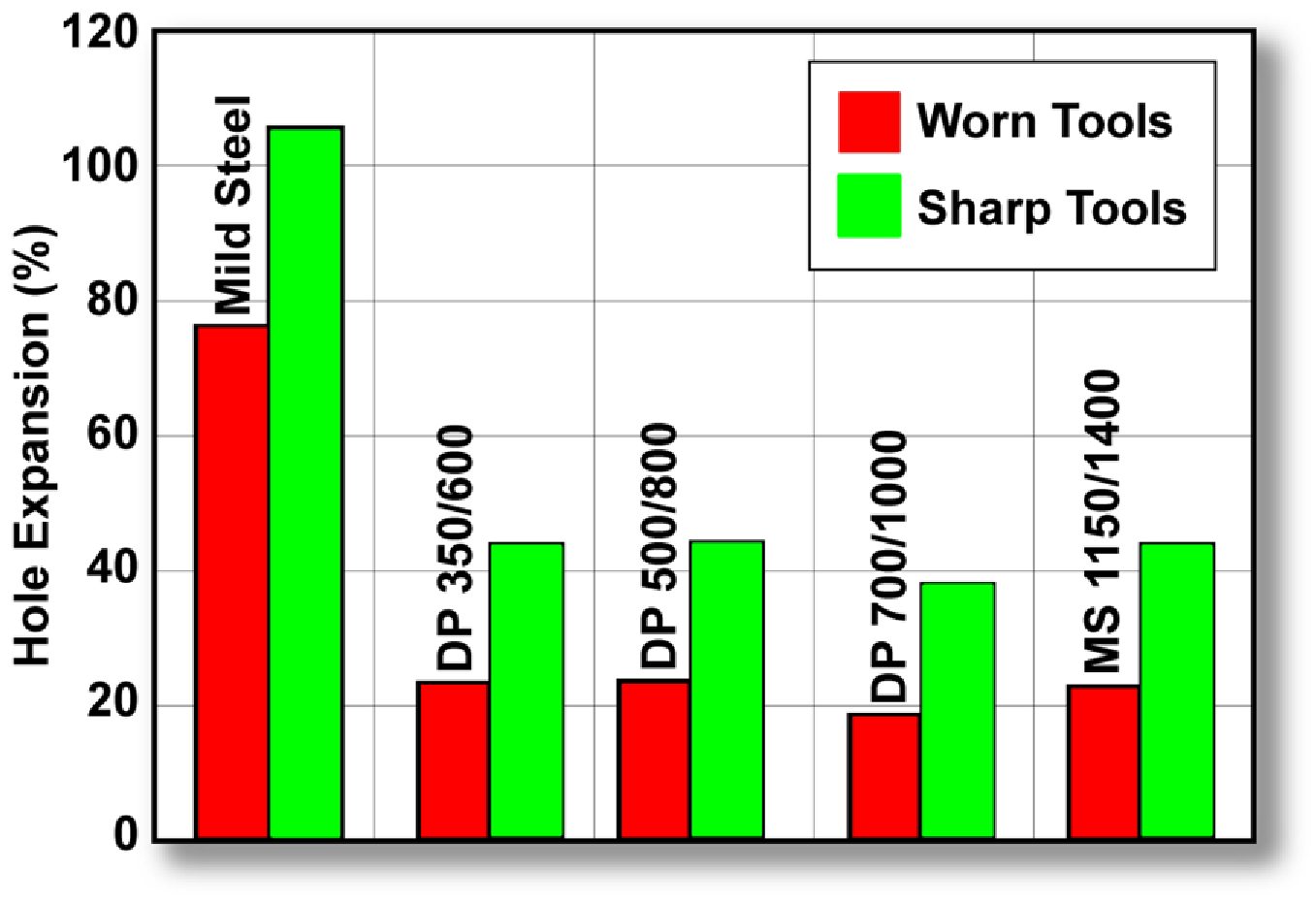

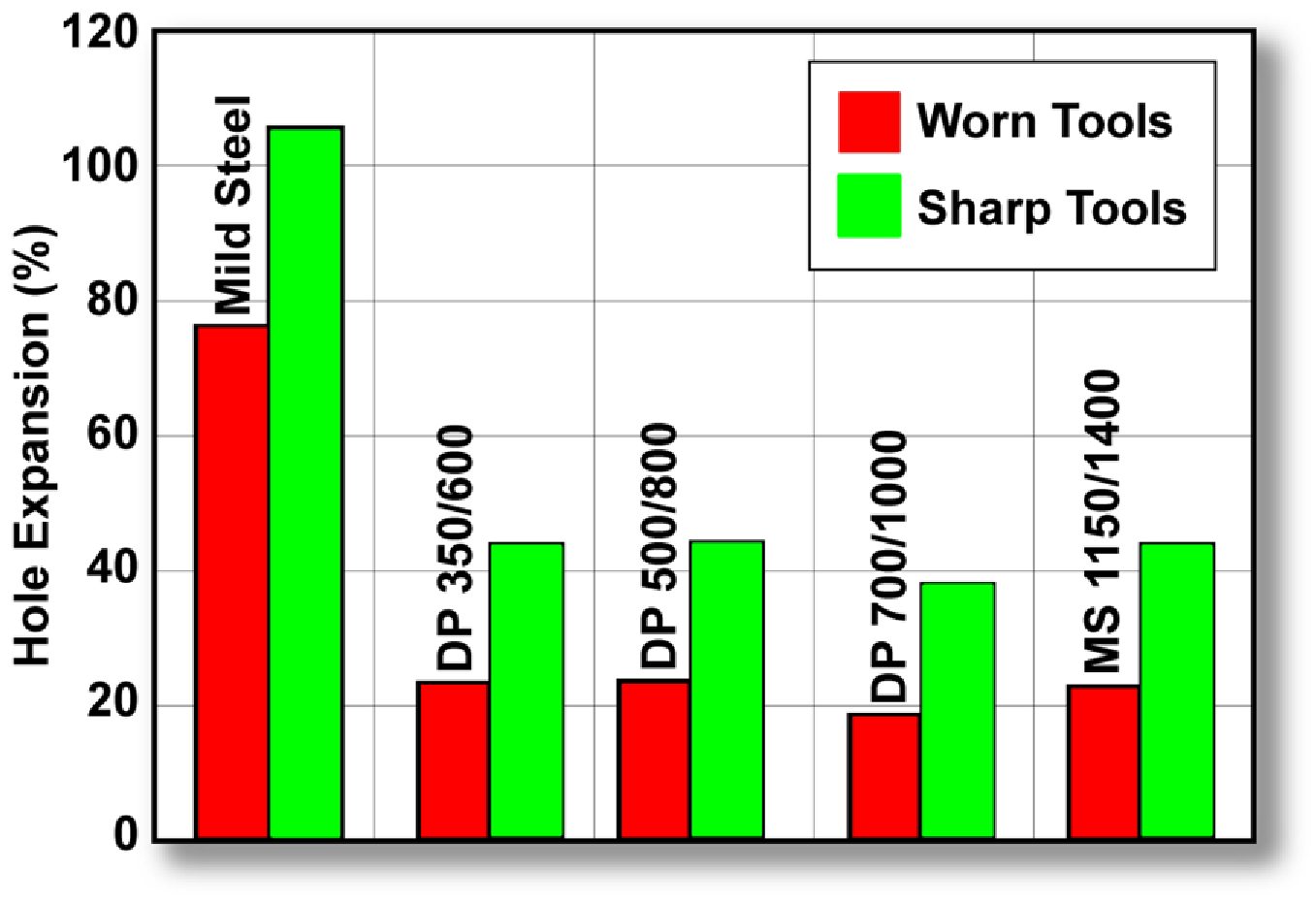

Over time, the targeted edge quality degrades and targeted clearance changes without proper attention. A study documented in Citation C-1 evaluated the hole expansion ratio created by hole punching tools as they wore in a production environment. Tools evaluated were made from 60 HRC uncoated Powder Metallurgy tool steels. Data in Figure 5 show the percent hole expansion from newly ground punches and dies (Sharp Tools) and from used production punches and dies (Worn Tools). The radial clearance was 0.1 mm. A rust preventative oil was applied to the steels during the punching; a lubricant oil was applied during hole expansion. Tool wear and possible micro-chipping resulted in a poor edge condition. The clearance was not significantly affected, but the steel edges suffered cold work which dramatically affected their hole expansion results.

Figure 5: Impact of production tooling condition on hole expansion performance. (tests conducted w 50 mm diameter conical punch).C-1

Conclusions from Citation C-1 include:

- The best quality edge condition will produce the best results

- Tooling must remain sharp and damage-free to maintain the consistency in edge conditions.

- The burr should be in contact with the punch rather than on the freely-expanding side

- Hard and wear resistant tools, such as those produced from coated powder metallurgy (PM) tool steels, are highly recommended.

Additional information on tool materials can be found here and other articles in that category.

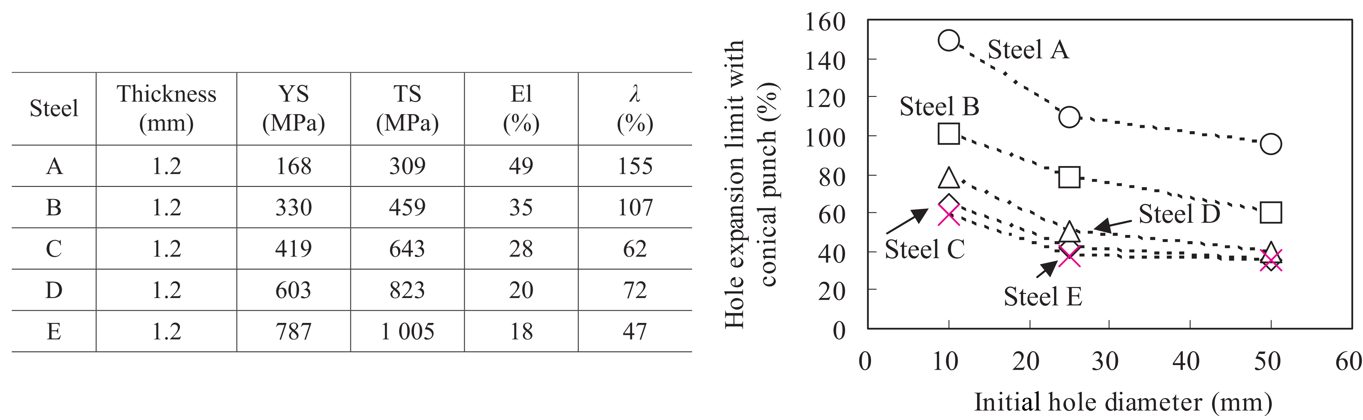

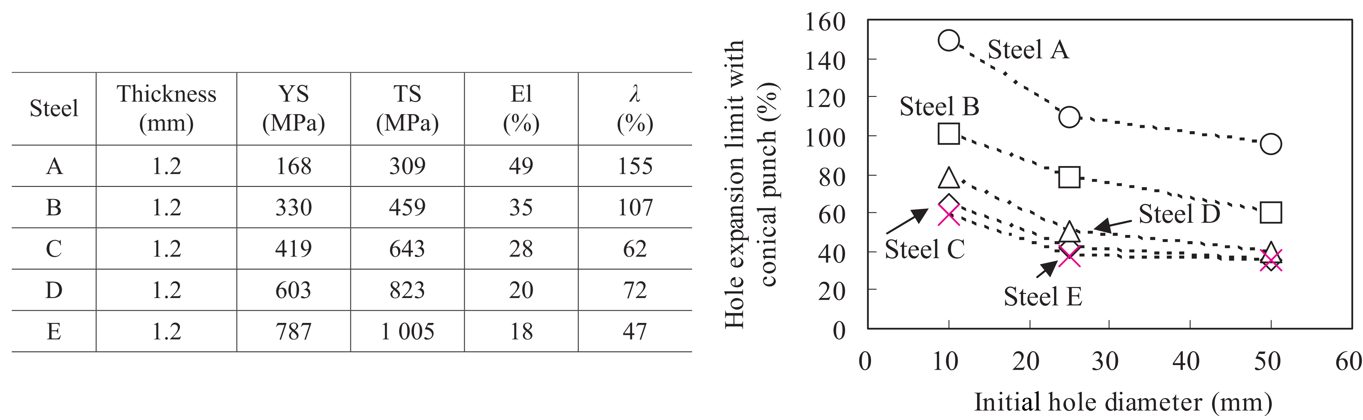

The ISO 16630 specificationI-9 eliminates one variable by prescribing the use of a 10 mm diameter hole, but it is important to understand that starting hole diameter influences the degree to which that hole can be expanded. A study that included mild steels to AHSS grades evaluated the effect of starting hole diameter.I-10 All steels were 1.2mm, punched with a clearance of 12.5%, and expanded with a conical punch having a 60° apex angle. As the starting diameter increases, the degree to which the hole can be expanded decreases, Figure 6. Note that as the strength increases, this effect appears to be minimized.

Figure 6: Hole Expansion Ratio Decreases as Initial Hole Diameter Increases.I-10

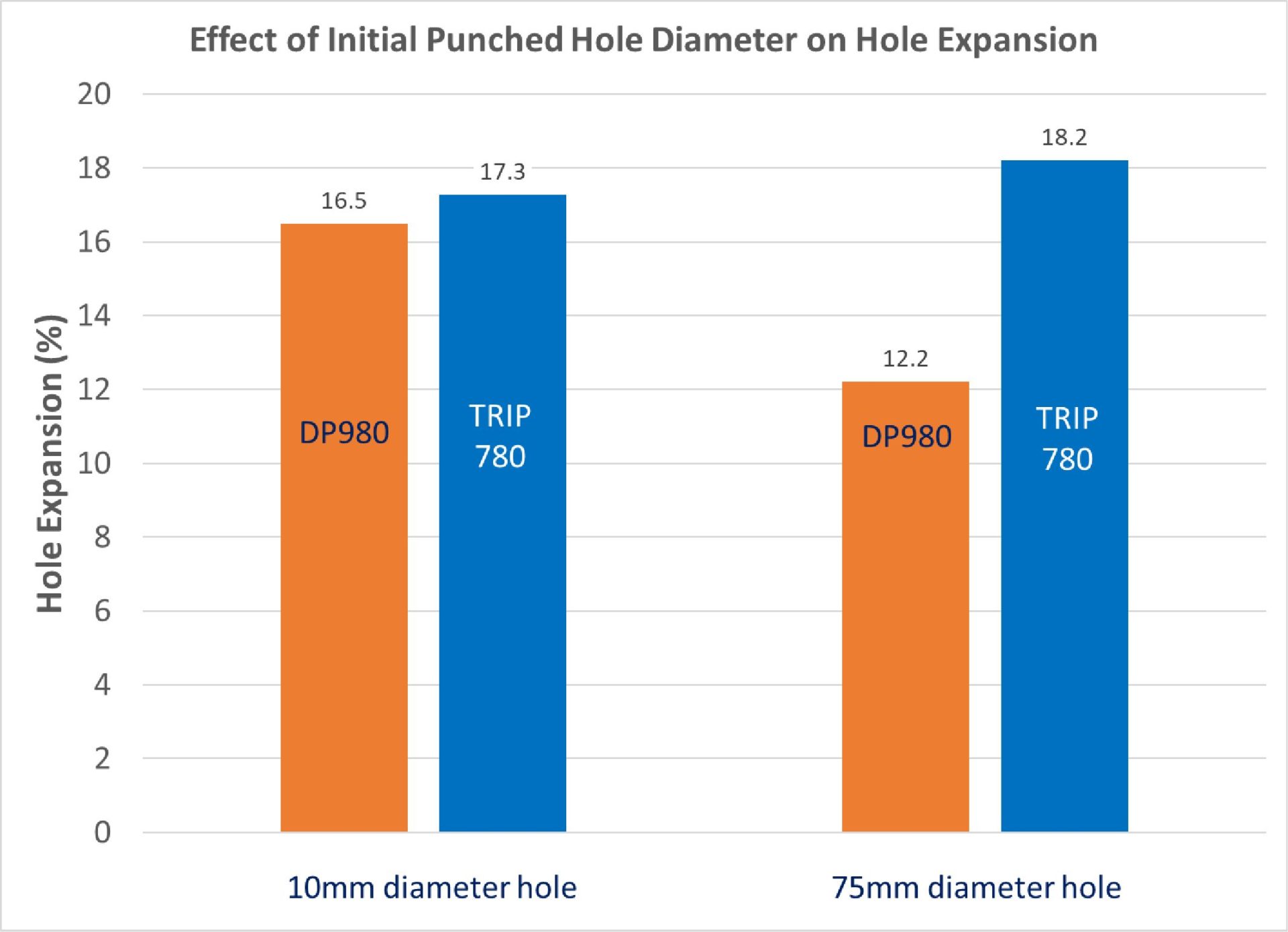

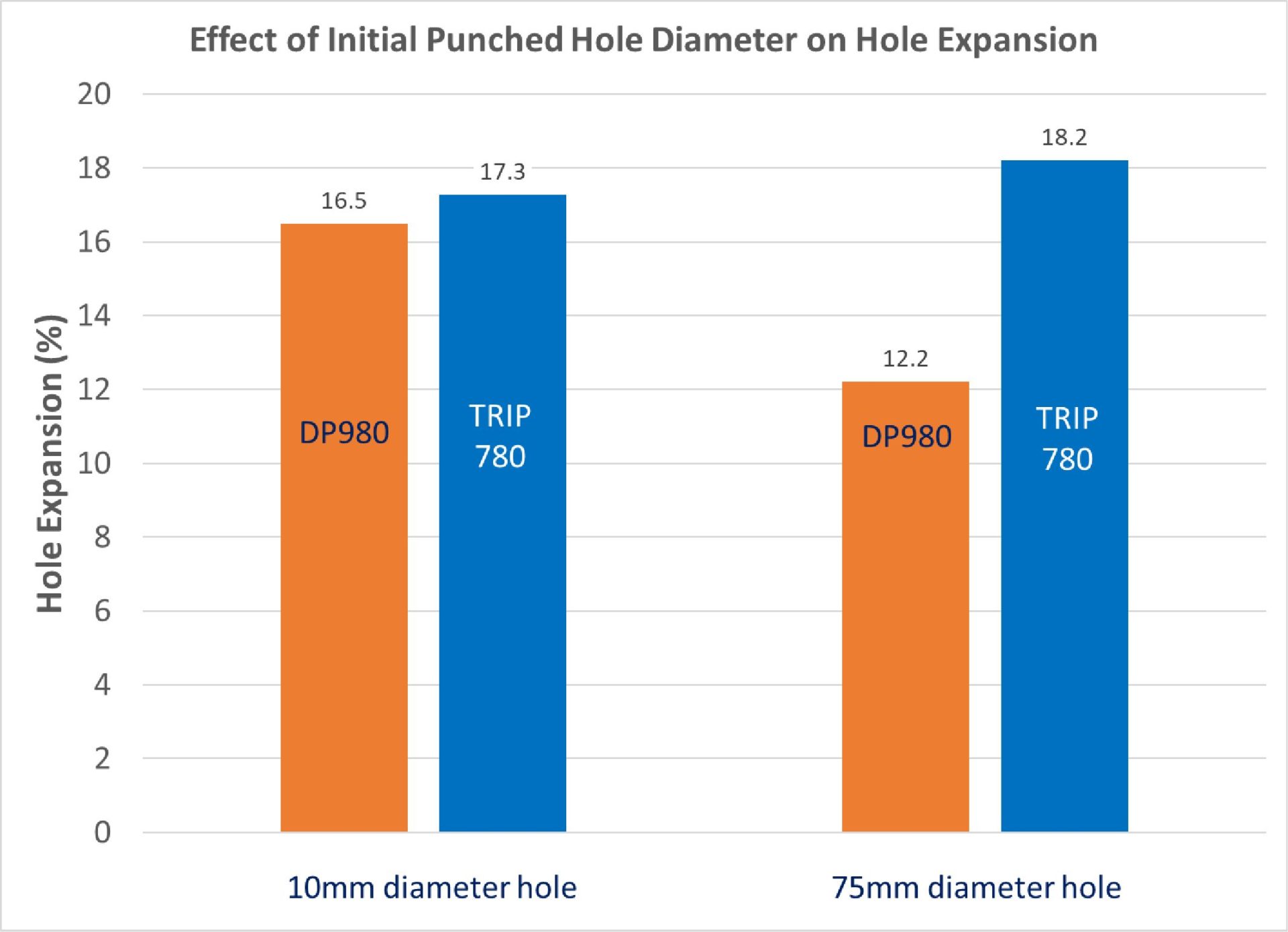

Increasing the starting hole diameter may help to distinguish between different grades.K-11 Similar hole expansion performance exists between DP980 and TRIP780 under ISO 16630 test conditions (punched 10 mm hole). It is easier to discern better performance in the TRIP780 product when performing a similar test with a 75 mm diameter punched hole (Figure 7).

Figure 7: Effect of Initial Punched Hole Diameter on Hole Expansion. (Based on Data from Citation K-11.)

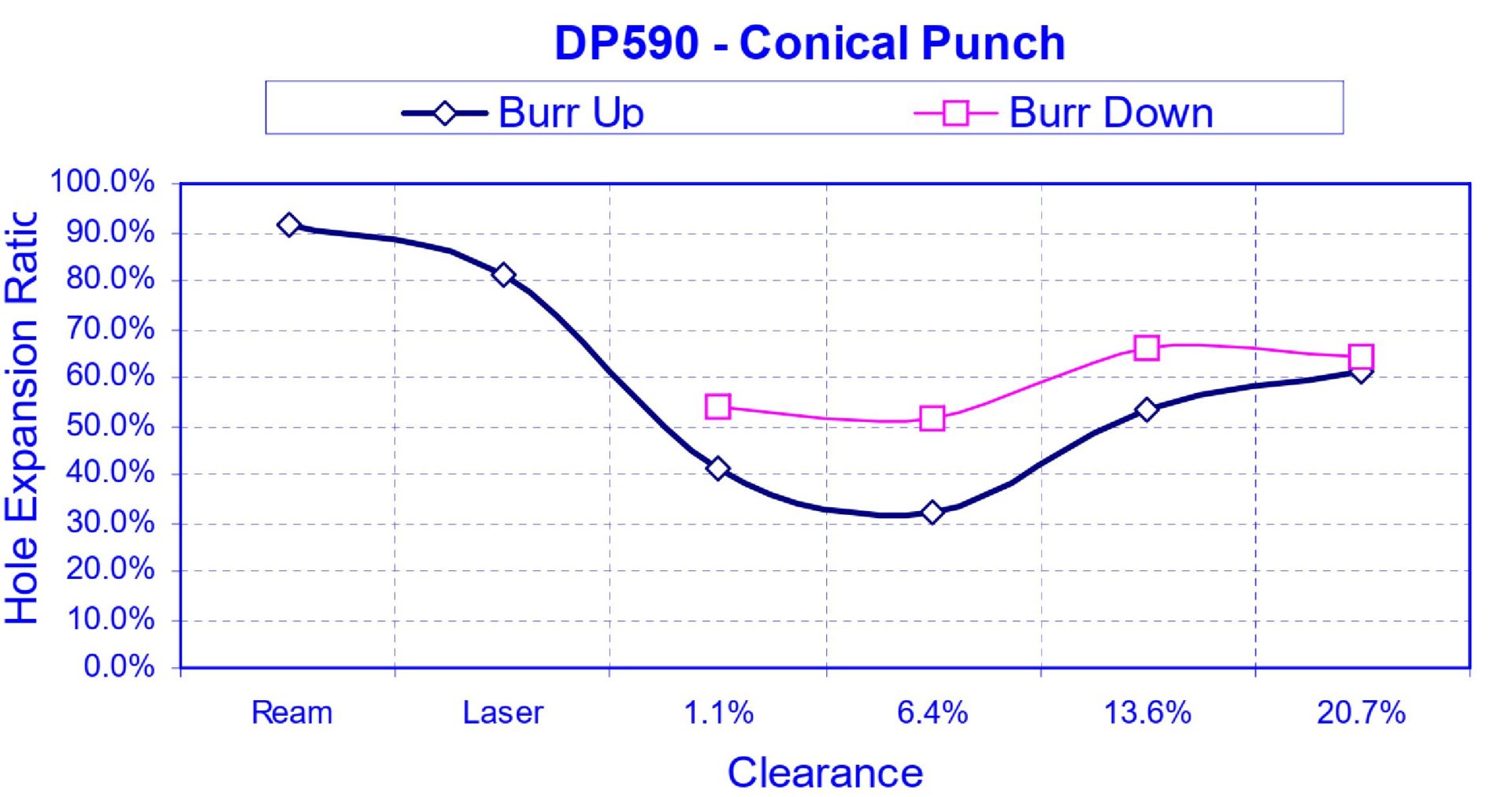

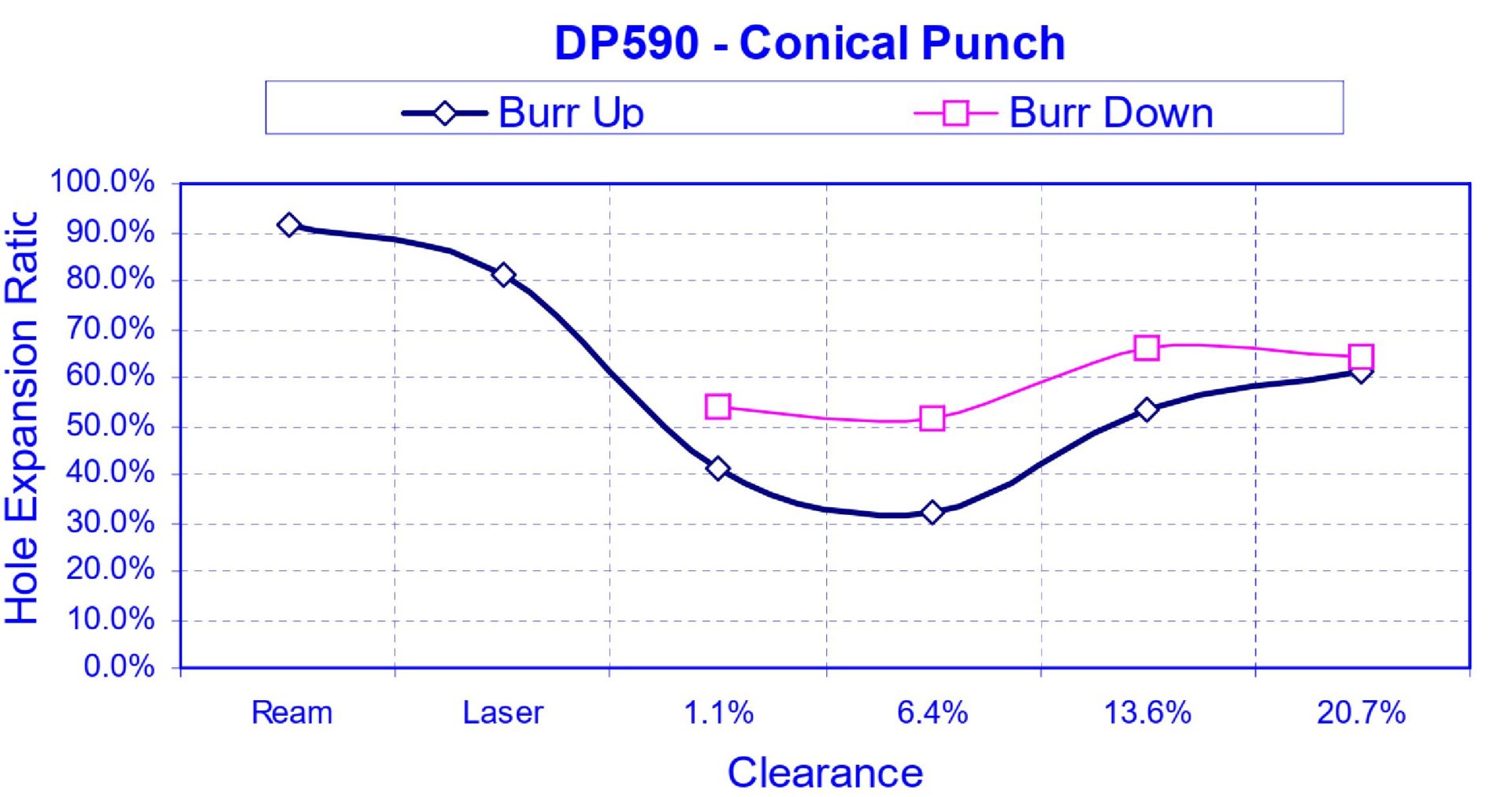

The position of the burr relative to the punch affects performance in a hole expansion test. Detrimental effects of an expanding edge are minimized If the burr is on the punch side. Having the burr on the punch side, rather than the freely expanding side, minimizes the detrimental effects of the expanding edge. The primary reason is the outer surface is in a greater degree of tension than the surface next to the punch.

Figure 8 examines the effect of edge condition and clearance on DP 590 expanded with a conical punch.K-10 The data suggests that there could be up to a 20% increase in sheared edge extension capability just related to the burr position on holes punched with conventional clearances. This should be considered in die processing materials and designs sensitive to edge expansion.

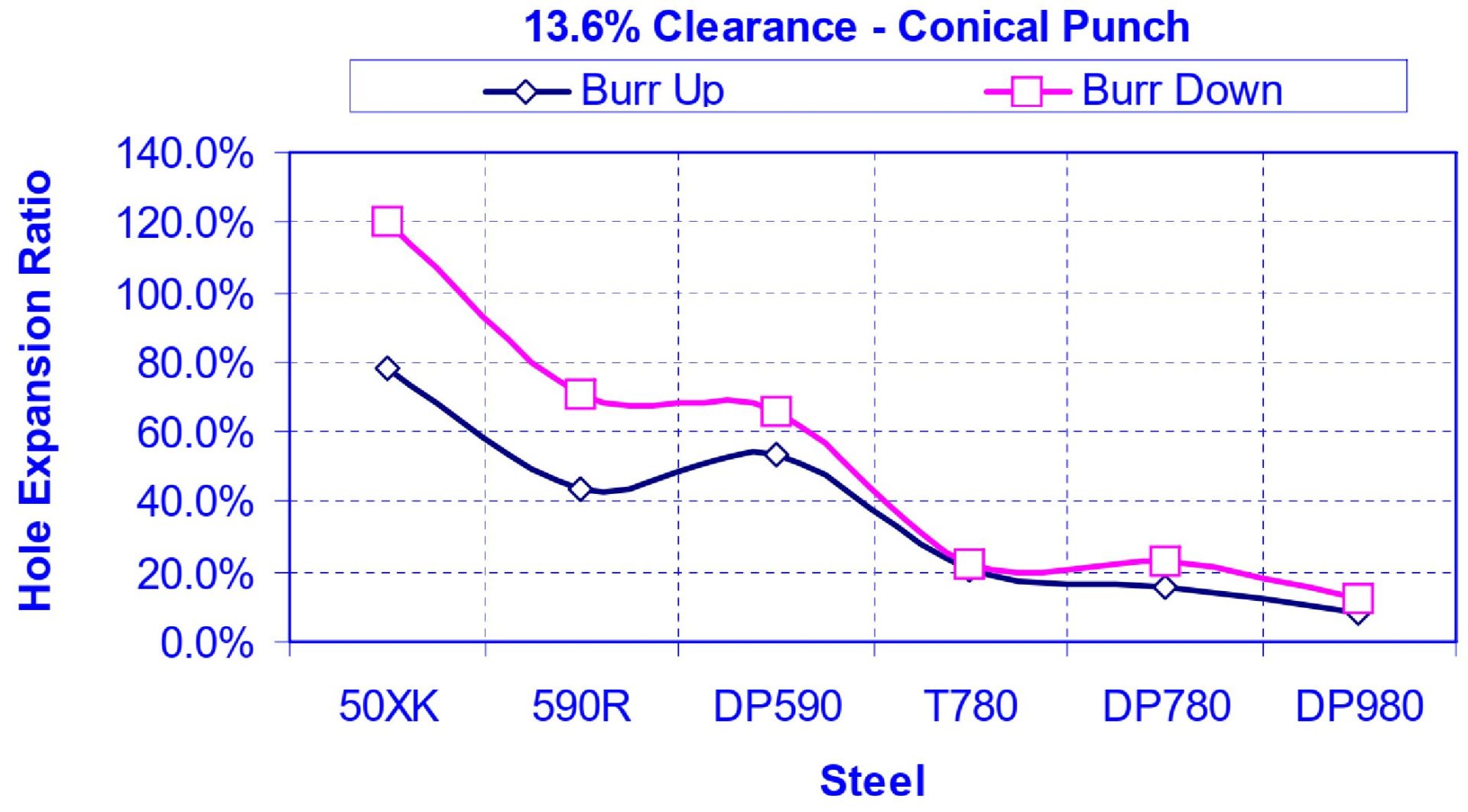

Figure 8: The Effect of Burr Orientation on Hole Expansion as a Function of Clearance on DP590. “Burr Up” means away from the punch; “Burr Down” means in contact with the punch.K-10

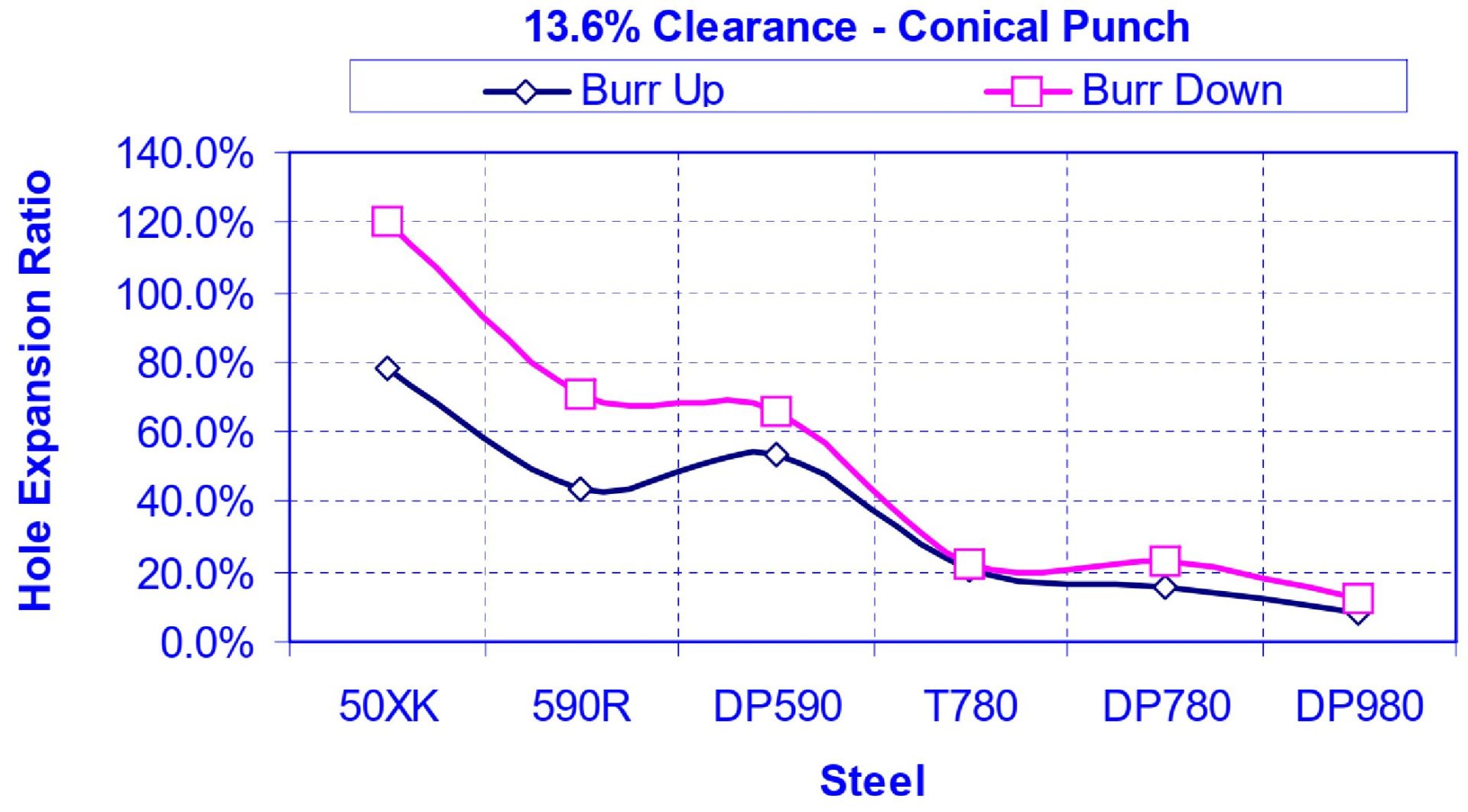

Shown in Figure 9 is the influence of burr orientation and material grade.K-10 The 50XK grade shown is HSLA 350Y/450T, where there is a significant improvement in the measured hole expansion related to the position of the burr relative to the punch. The magnitude of this difference decreases as strength increases, but persists for all grades tested.

Figure 9: The Effect of Burr Orientation on Hole Expansion as a Function of Different High Strength Steel Grades “Burr Up” means away from the punch; “Burr Down” means in contact with the punch.K-10

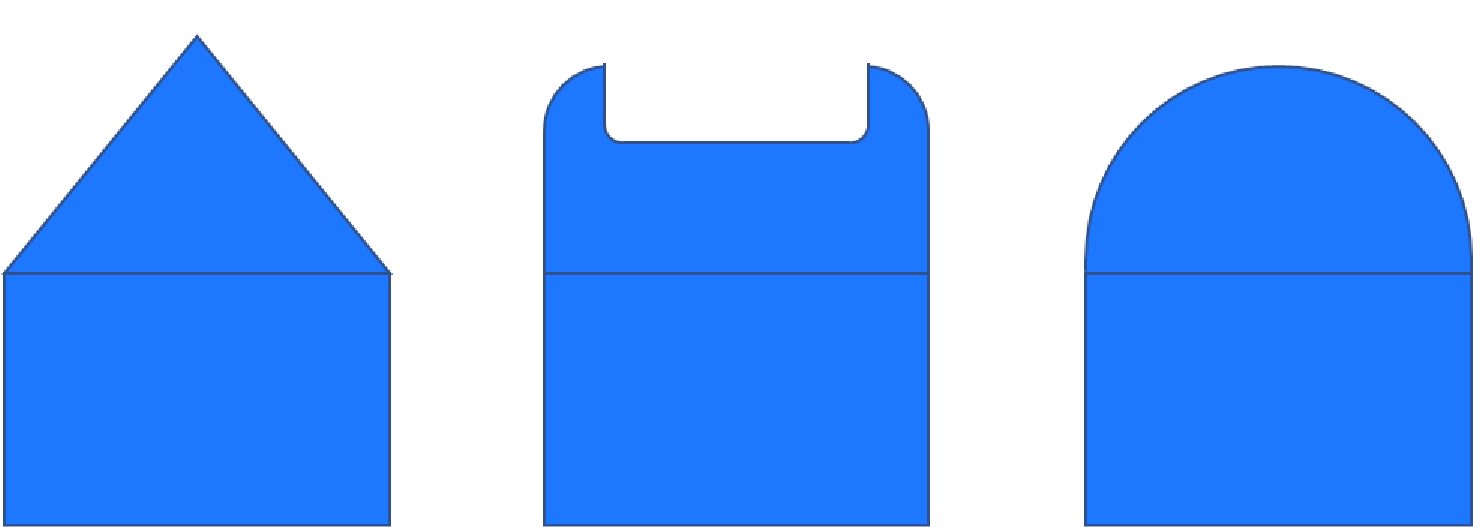

The shape of the punch used to expand the hole impacts the degree to which it can be expanded. Figure 10 shows generalizations of the three most-common shapes: a conical punch, a flat punch, and a hemispherical punch.

Figure 10: Sketches of Punches Used for Hole Expansion: Conical, Flat, and Hemispherical.

Metal motion and appearance changes depending on the type of punch used. Using a conical punch leads to the shape shown in Figure 11a, with a flat punch leading to the appearance shown in Figure 11b.S-3 The operations are sometimes described as hole expansion when accomplished with a conical punch, and hole extrusion with use of a flat punch.

Figure 11a: Sample appearance after testing with conical punch.S-3

Figure 11b: Sample appearance after testing with flat punch.S-3

The ISO 16630 hole expansion test specifies the use of a conical punch with a 60 degree apex angle. Here, the free edge undergoes stretching and bending. Using a flat punch instead of a conical punch eliminates the bending component, and all deformation is from only edge stretching. These strain state differences lead to different sheared edge extension performance, with greater expansion prior to cracking achieved with holes expanded using a conical punch. This improved performance with conical rather than flat punches has been attributed to the presence of the bending component.N-10 Edge condition does not appear to influence hole expansion capability when a flat bottom punch is used.

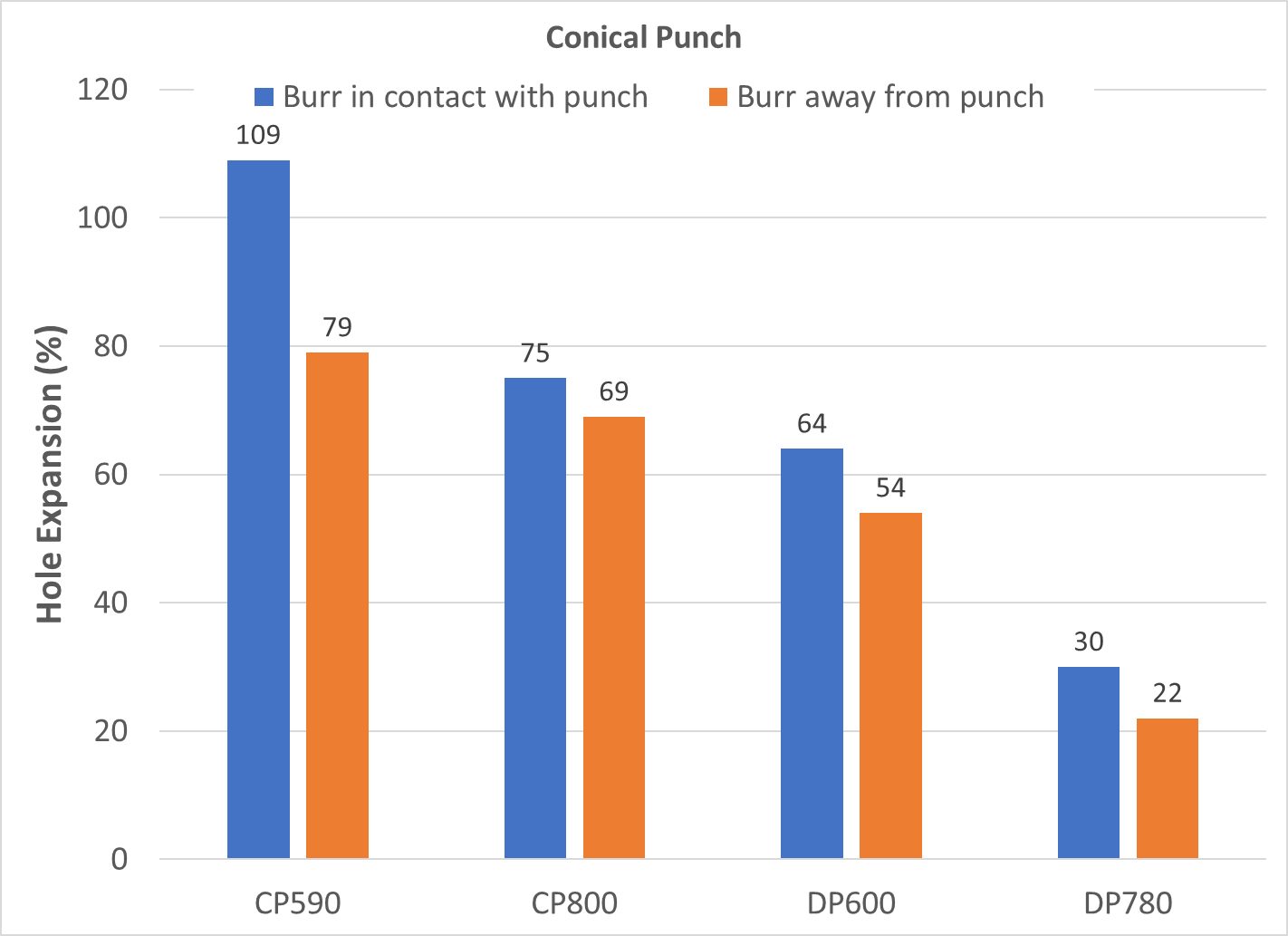

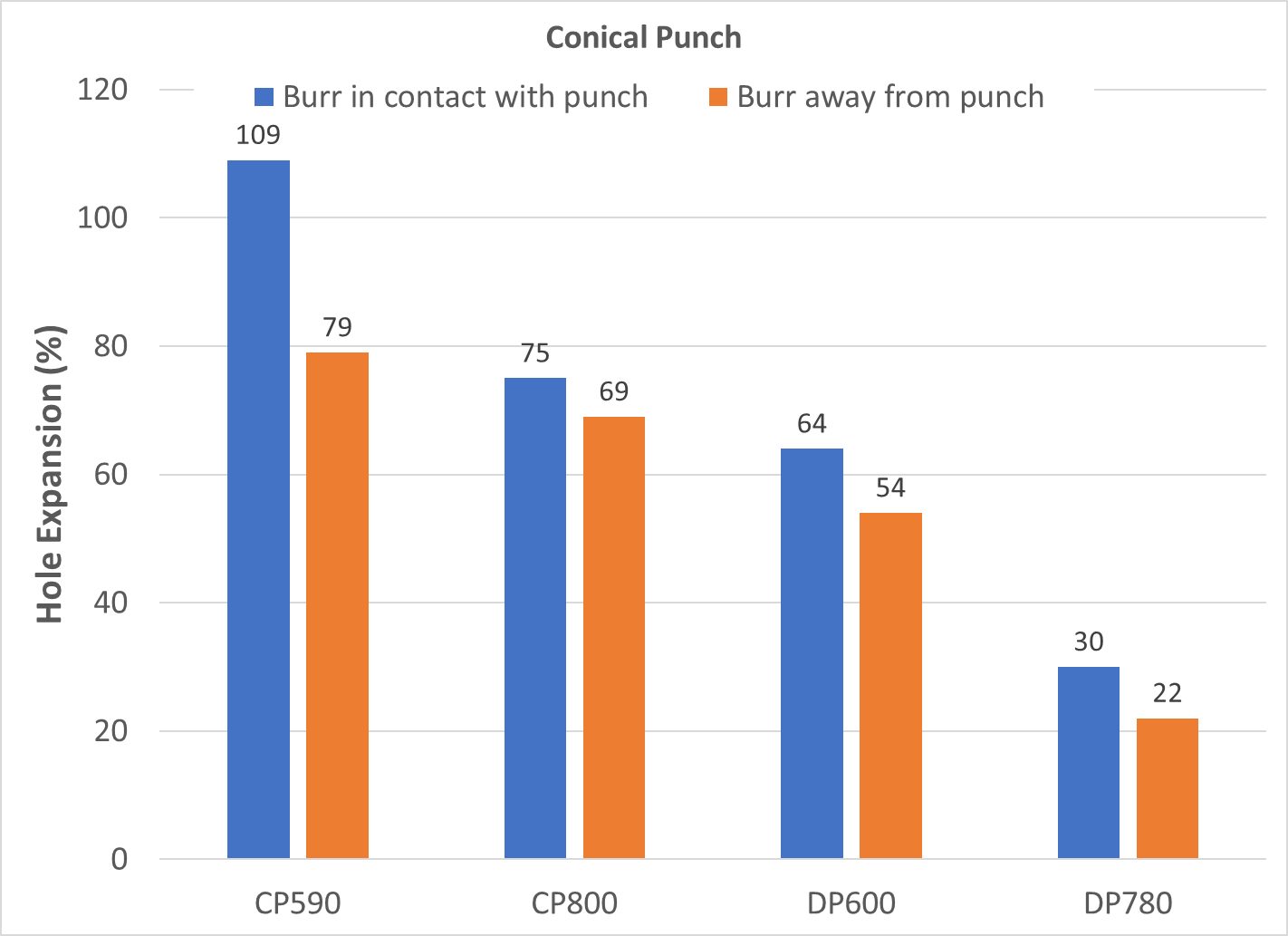

Shown in Figures 12 to Figure 15 are the effects of burr orientation and punch type, which vary as a function of metal grade. Figure 16 compares the performance of reamed holes when expanded with either conical or flat punches. Where the tested grades perform similarly when expanded with a flat punch, the conical punch leads to exceptional performance of reamed holes of 3 of the 4 grades. The relatively poor performance of the DP780 grade may be due to the hardness differences between the ferrite and martensite components, noting that there is more martensite in DP780 than DP 600. In the study from which the data was taken, the complex phase steels had a yield/tensile ratio of approximately 87%, while for the dual phase grades the yield/tensile ratio was approximately 60%.P-13

Figure 12: Effect of Burr Orientation on Hole Expansion from a Conical Punch. (Based on Data from Citation P-13.)

![Figure 13: Effect of Burr Orientation on Hole Expansion from a Flat Punch [Based on Data from Reference 11]](https://ahssinsights.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/Pasted-into-Hole-Expansion-Testing-Intro-31.jpg)

Figure 13: Effect of Burr Orientation on Hole Expansion from a Flat Punch. (Based on Data from Citation P-13.)

![Figure 14: Effect of Punch Type on Hole Expansion of Sheared Holes with Burr In Contact With The Punch [Based on Data from Reference 11]](https://ahssinsights.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/Pasted-into-Hole-Expansion-Testing-Intro-32.jpg)

Figure 14: Effect of Punch Type on Hole Expansion of Sheared Holes with Burr In Contact With The Punch. (Based on Data from Citation P-13.)

![Figure 15: Effect of Punch Type on Hole Expansion of Sheared Holes with Burr Facing Away From The Punch [Based on Data from Reference 11]](https://ahssinsights.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/Pasted-into-Hole-Expansion-Testing-Intro-33.jpg)

Figure 15: Effect of Punch Type on Hole Expansion of Sheared Holes with Burr Facing Away From The Punch. (Based on Data from Citation P-13.)

![Figure 16: Effect of Punch Type on Hole Expansion of Reamed Holes [Based on Data from Reference 11]](https://ahssinsights.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/Pasted-into-Hole-Expansion-Testing-Intro-34.jpg)

Figure 16: Effect of Punch Type on Hole Expansion of Reamed Holes. (Based on Data from Citation P-13.)

Figure 17 compares the simulation results from expanding a perfect edge (no burr, no strain) with a conical punch on the left and a spherical punch on the right.W-2 The color scale, based on a “damage” parameter, shows that a spherical punch results in a more uniform distribution of damage, especially at the edge. This suggests that the impact of burr orientation on hole expansion is less significant for this punch geometry.

Flanging with a conical punch causes high circumferential strain and high damage values at the outer edge. The inner edge of the sheet initially presses against the punch, and later stretches during flanging. Since cracks initiate at the fracture zone, using a conical punch with the burr facing the punch leads to a greater hole expansion capability than when having the burr in contact with a spherical punch.

Fracture initiates at the edge, and orienting the burr so that it is in contact with the punch leads to a greater hole expansion value.

Figure 17: Distribution of damage values in simulated hole expansion tests conducted with a conical punch (left image) and a hemispherical punch (right image).W-2

Improving Hole Expansion with New Punch Shapes

As explained above, the degree to which a sheared edge can be stretched before fracture is a function of many parameters, including the shape of the punch. Also contributing is the hardness uniformity of the microstructural phases, where grades with components having high hardness differences are associated with relatively lower hole expansion capability.

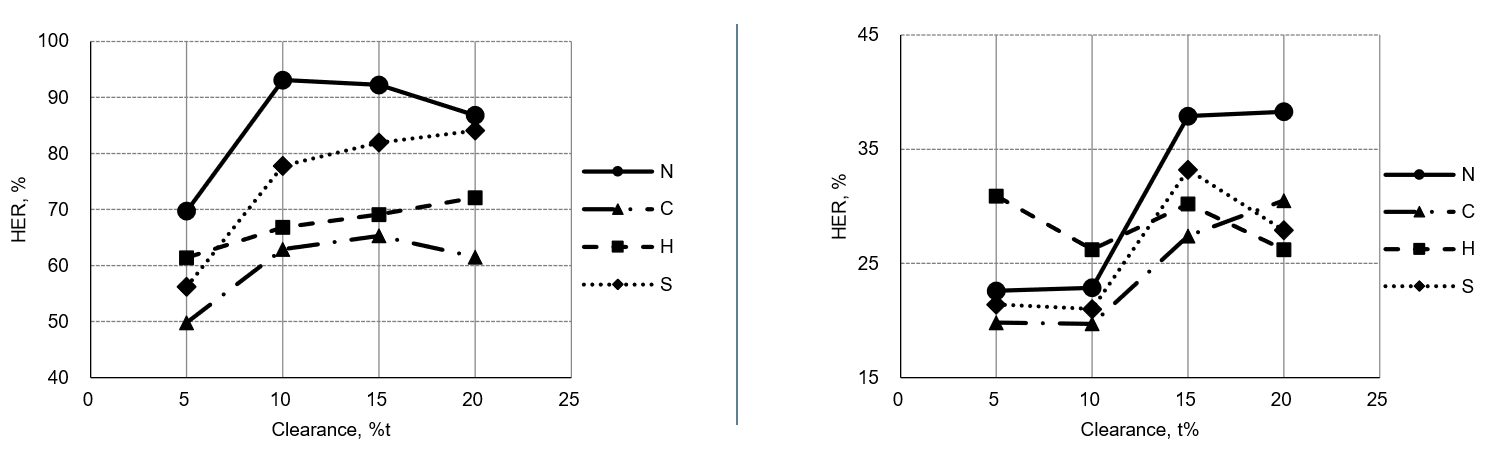

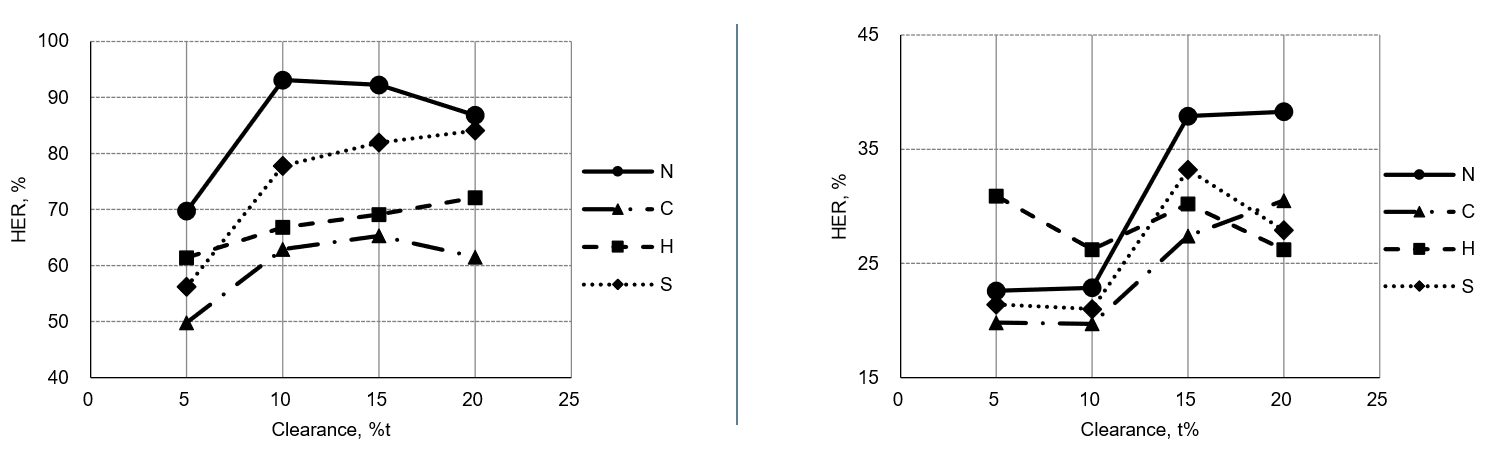

Researchers evaluated the effects of punch design and clearance on hole expansion capability of dual phase and ferrite-bainite steels, each with a tensile strength of approximately 780 MPa.L-47

In addition to a conventional flat punch face, other punch types studied were those with a beveled face, a humped shape, and a newly designed punch which combines the benefits of the prior two types. A chamfered or beveled punch is known to reduce punch forces and reverse snap-through loads, while at the same time improve edge quality and hole expansion by minimizing the hardness increases found in the shear affected zone.

Use of the humped punch (Figure 18) led to hole expansion improvements of up to 10%, compared with a conventional flat punch when testing either the DP or FB products. When comparing the edge characteristics, the humped punch results in an increased rollover zone. The authors attributed this to the hump geometry imposing axial tension on the steel during punching, thereby increasing stress triaxiality. Increases in stress triaxiality results in a reduction in effective stress even at the same average stress. This in turn lowers the plastic deformation at the sheared edge which minimizes edge fracture. For these reasons, the increases in stress triaxiality associated with the humped punch promotes higher levels of hole expansion.

Figure 18: Humped punch design used in Citation L-47.

A newly designed punch which combines a beveled and humped design (Figure 19) increases hole expansion by more than 30% in both dual phase and ferrite-bainite steels (Figure 20). As explained above, the newly designed punch is effective in promoting stress triaxiality and minimizing the plastic deformation near the sheared edge. Furthermore, the beveled design improves the shear affected zone (SAZ) characteristics, leading to improved sheared edge expandability as measured in a hole expansion test.

Figure 19: New punch design incorporating features of beveled and humped punches.L-47

Figure 20: Effect of punch type and clearance on the hole expansion ratio of 780 MPa tensile strength steels. Left graph represents ferrite-bainite steel; right graph represents a dual phase steel. Legend: N=new punch design; C=conventional; H=humped; S=shear (beveled).L-47

Correlation of Hole Expansion Ratio with Tensile Properties

The complexities of hole expansion testing, as well as relatively few laboratories with the necessary test equipment and expertise, have led researchers to look for a correlation between the hole expansion ratio and conventionally measured properties obtained from a tensile test like the yield and tensile strength, uniform and total elongation, n-value, and r-value. Researchers even studied manipulations such as the yield-to-tensile ratio, tensile strength multiplied by uniform elongation, and n-value multiplied by r-value. Unfortunately, none of these properties or combinations have suitable correlation with the hole expansion ratio.

Recent work has shown a promising correlation between the hole expansion ratio and the true thinning strain at fracture. Our article on true fracture strain, describes this in greater detail.

![Figure 13: Effect of Burr Orientation on Hole Expansion from a Flat Punch [Based on Data from Reference 11]](https://ahssinsights.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/Pasted-into-Hole-Expansion-Testing-Intro-31.jpg)

![Figure 14: Effect of Punch Type on Hole Expansion of Sheared Holes with Burr In Contact With The Punch [Based on Data from Reference 11]](https://ahssinsights.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/Pasted-into-Hole-Expansion-Testing-Intro-32.jpg)

![Figure 15: Effect of Punch Type on Hole Expansion of Sheared Holes with Burr Facing Away From The Punch [Based on Data from Reference 11]](https://ahssinsights.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/Pasted-into-Hole-Expansion-Testing-Intro-33.jpg)

![Figure 16: Effect of Punch Type on Hole Expansion of Reamed Holes [Based on Data from Reference 11]](https://ahssinsights.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/Pasted-into-Hole-Expansion-Testing-Intro-34.jpg)