Vehicle programs must balance performance, safety, fuel efficiency, affordability and the environment, while maintaining designs that are appealing to customers. Use of higher strength steels allows for a reduction in the sheet metal thickness and in turn vehicle mass. The increased ductility offered by Advanced High Strength Steels facilitates part consolidation also contributing to lower weight and manufacturing cost while providing an efficient way to increase component and vehicle stiffness.

Low-density materials like aluminium, magnesium and composites have widespread use in luxury class vehicles, where amenities, comfort, and speed are prioritized over affordability. Penalties for not meeting fuel economy and emissions mandates are easily absorbed in the sales price.

On mass-market vehicles, where per-unit emissions are multiplied over higher volumes, automakers target selecting the most efficient way to achieve the lowest total emissions.

Compared with the limited number of low-ductility steels available decades ago, the lower density materials would have offered an easy but costly path to lightweighting. Back then, since there were not that many high-strength options, vehicle crashworthiness was improved by increasing thickness.

However, increasing metal strength allows for a thickness reduction while maintaining crash performance. The substantially higher strength steels available today have sufficient ductility to form complex stampings from sheets thin enough to be weight-competitive with components formed from lower-density materials that must be made from higher thickness to have comparable stiffness.

The spectrum of steel grades commercially available today have:

- higher strength, greatly contributing to the crash-energy management approach.

- higher ductility that allows for additional shape to be formed into the component, also increasing stiffness and potentially allowing for part consolidation,

- higher modulus than aluminium or magnesium that inherently leads to a stiffer component.

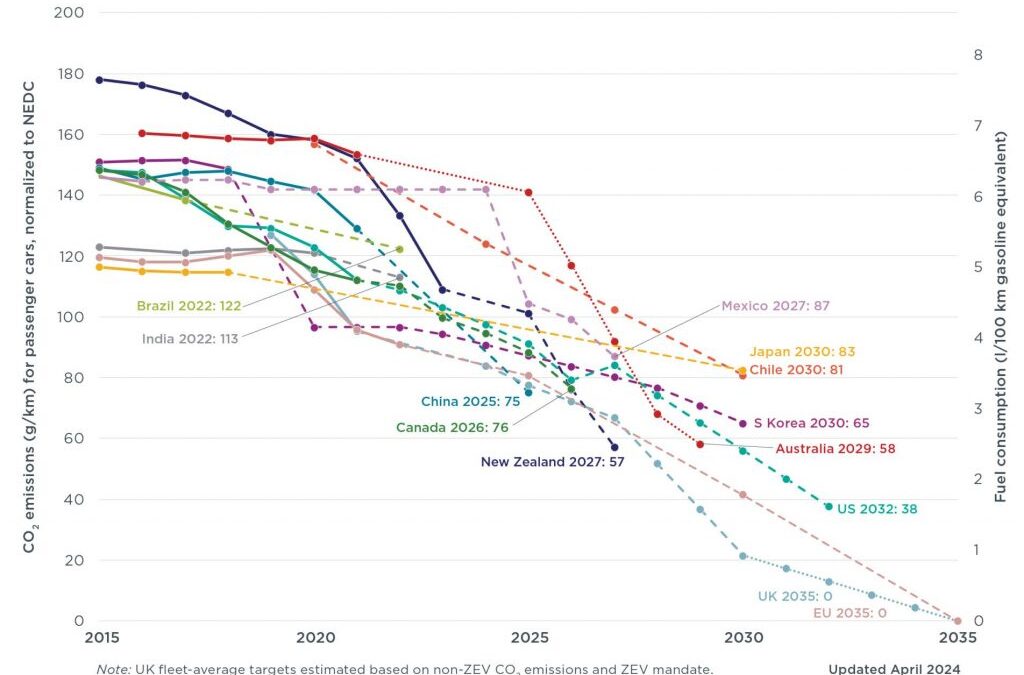

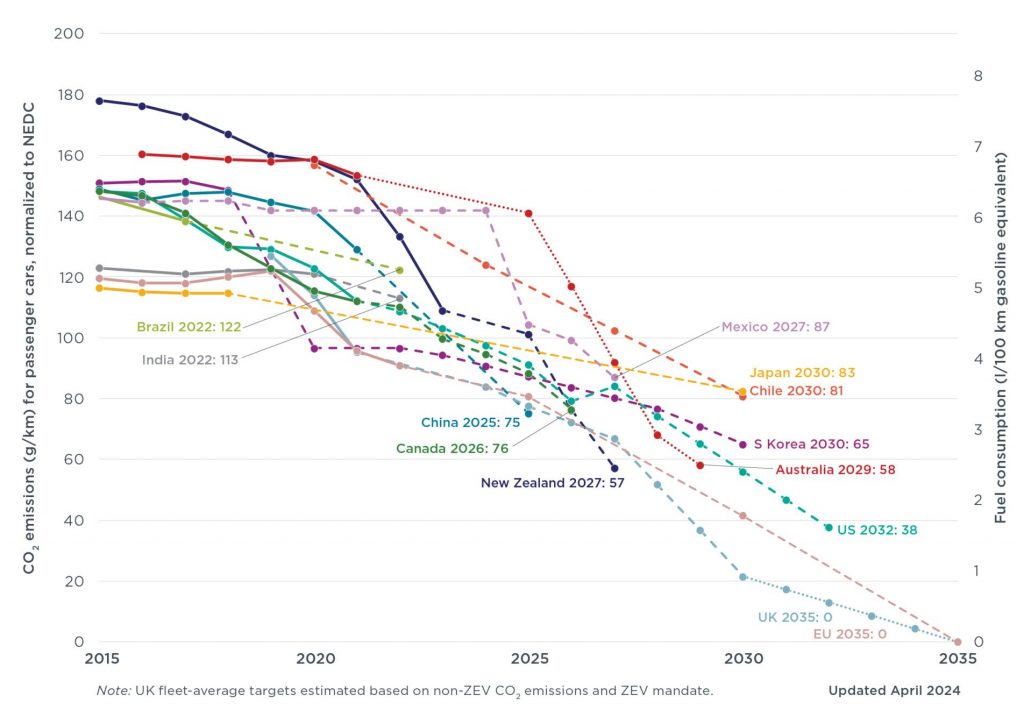

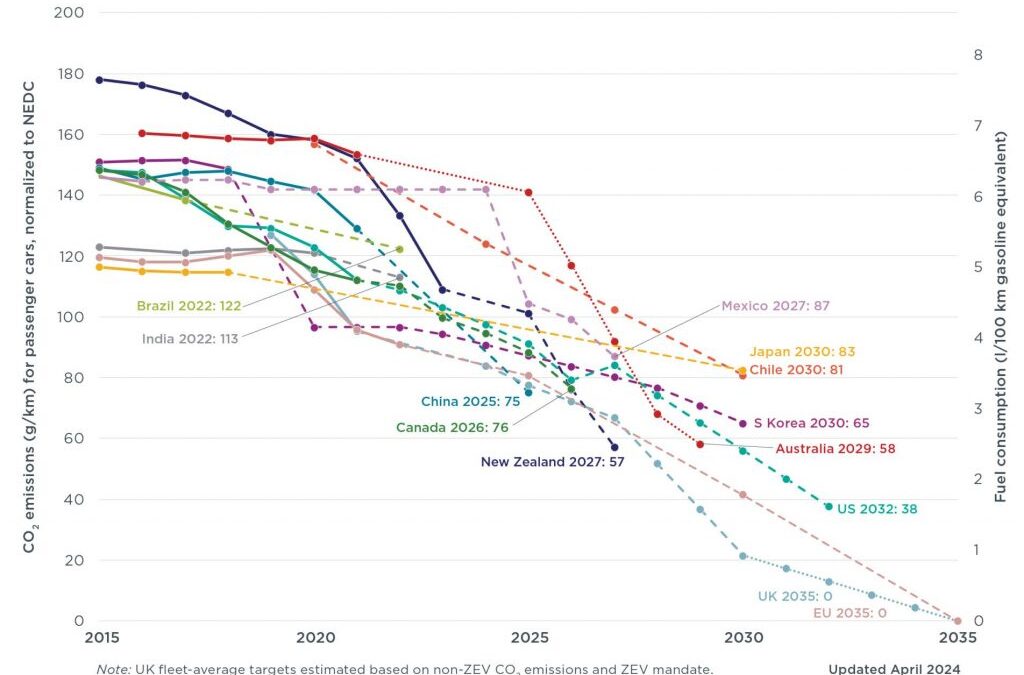

Recent years have seen an increased global sensitivity to tailpipe emissions, with Figure 1 highlighting regulations for passenger cars in different countries and regions. Many major markets have committed to fleet average emissions below 100 g CO2/km, and we’re on a negotiated global journey to Net Zero Emissions by 2050.

Figure 1: Passenger car emissions and fuel consumption targets, normalized to New European Driving Cycle I-2

The problem with the current regulation of automotive greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions is their focus solely on tailpipe emissions, produced from fuel combustion during vehicle use. The regulations ignore other significant sources of GHG emissions in the vehicle’s life cycle including vehicle production (including the emissions from material production) and treatment of the vehicle at the end of its useful life. This omission comes with serious risks. An unintended effect of this approach is an over-emphasis on vehicle lightweighting. While lightweighting can be an effective tool to reduce vehicle emissions, it must be done with a holistic knowledge of the implications related to the total vehicle life cycle GHG emissions.

Reducing vehicle mass decreases fuel consumption, which also reduces tailpipe emissions. This may, or may not, offset the increased production emissions from material production of the lower density materials. One possibility is that the reduction of emissions in the use phase results in overall lower emissions, but because of the trade-off between the use phase and production emissions, the result is not as low as predicted by a tailpipe-only metric – some of the use-phase savings is offset by the increased production emissions. Also possible is where the use phase savings and the production phase increase are approximately equal, resulting in no net savings at all. In the other extreme, the production emissions outweigh the use phase savings, resulting in the unintended consequences of an increase in the overall emissions. This last scenario is the very opposite of what government policy intends, but happens regularly when vehicles constructed with low density materials don’t reach their intended vehicle life.

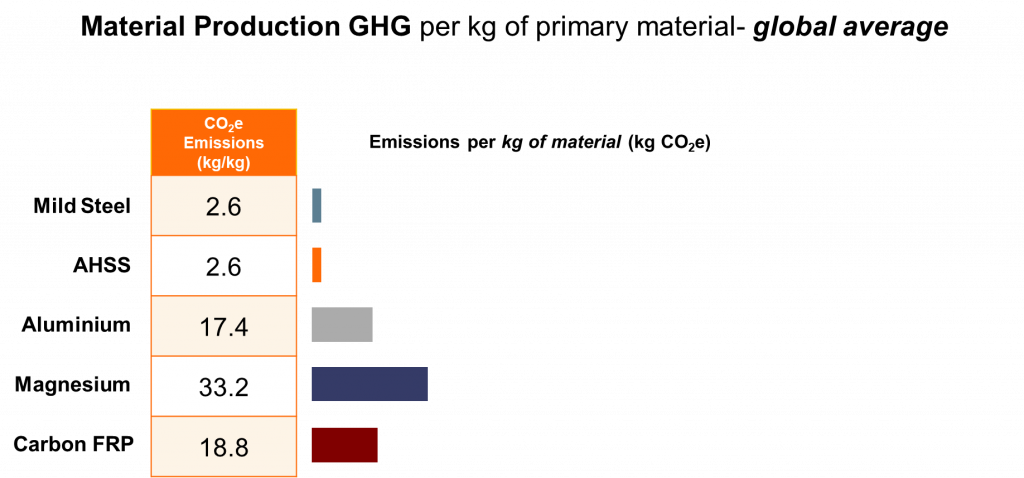

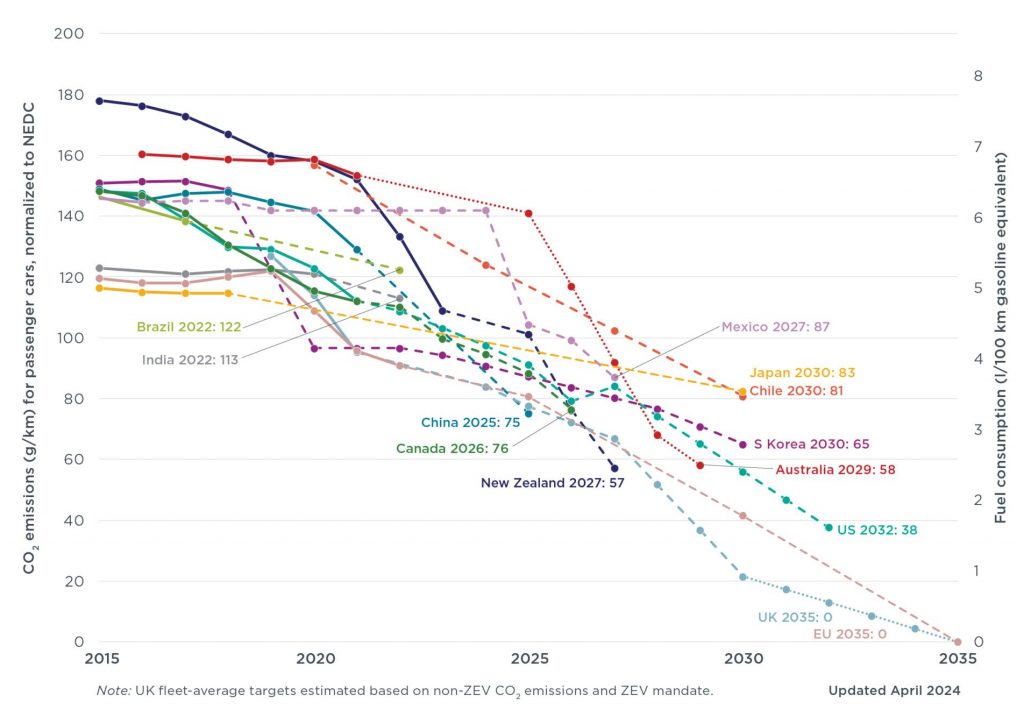

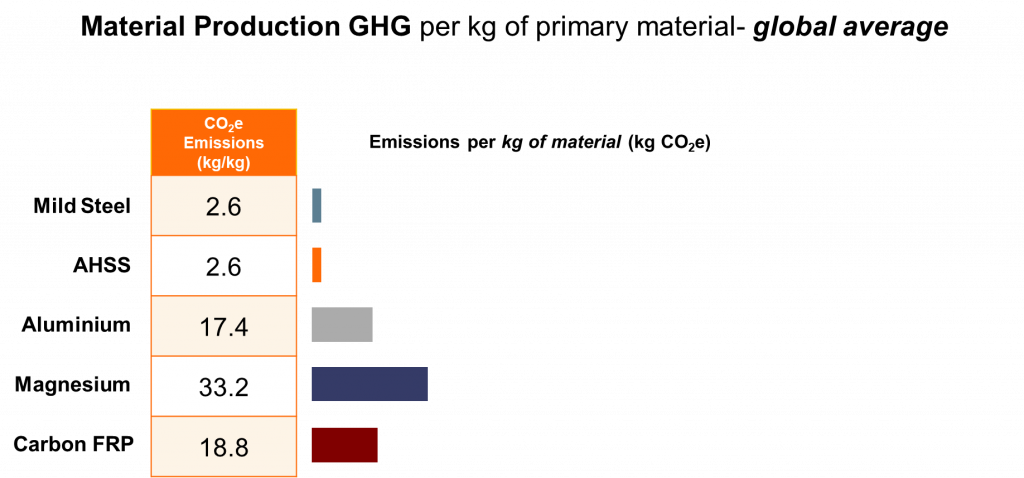

One of the perceived advantages to using materials of lower density is the expectation that they will result in lower GHG emissions. To illustrate why this is not true, consider the emissions from the material production stage of a typical automotive component. The mid-range GHG values for each material are taken from the above chart and then multiplied by the projected material weight that is required to make a hypothetical component. (The actual mass for an equivalent component varies based on the material used and the component design.)

Figure 2: Material average GHG emissions from primary production, in kg CO2e per kg of material.W-40

Furthermore, low-density materials create an offsetting emissions problem, as production of these materials is GHG-intensive, and therefore costly to the environment. The production of these alternative materials can produce 7 to 20 times more emissions than steel, as shown in Figure 2.

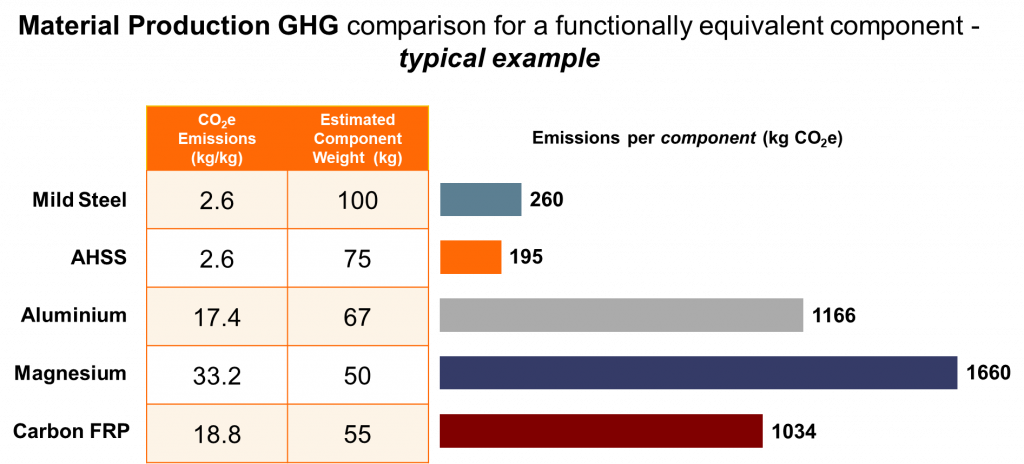

Figure 3: Material GHG emissions in kg CO2e for functionally equivalent generic components.W-40

Figure 3 shows that the use of lower density materials does not necessarily mean a reduction in greenhouse gas emissions. Although less weight is required for some alternative materials to achieve the same component functional performance, the emissions from the material production stage can still be many times higher than those of the baseline component. Therefore, the increase in material production emissions may outweigh the reduction in use phase emissions even after factoring in the mass savings benefit.

Vehicles are transitioning to alternative-energy powertrains and away from those based on fossil fuels. In these new-energy vehicles powered entirely by renewable electricity, emissions from the vehicle production stage, which includes material production, could account for as much as 95% of total emissions. In this scenario, the usage phase accounts for a mere 5% of the lifetime emissions. This is the opposite of what is found with vehicles having conventional Internal Combustion Engine (ICE) powertrains. For this reason, use of low GHG material such as steel becomes even more important as the world moves towards a renewable future.

Life Cycle Assessment

Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) is an environmental accounting methodology that considers a product’s entire life cycle, with cradle-to-grave assessments typically including impacts from raw material extraction and production (manufacturing phase), through its useful life (use phase), and to the end-of-life disposal or recycling of the product (end-of-life phase). It also takes into account the full life cycle of energy sources used across all lifecycle phases. This process illuminates any potential trade-offs between phases and highlights the true environmental impact, beyond the focus on tailpipe-only emissions.

Recent years have seen a greater adoption of using Life Cycle Assessment to assess a vehicle’s true environmental impact rather than solely focusing on what comes out of the tailpipe. LCA accounts for the total emissions including those coming from material production, vehicle use, and the chosen end-of-life path. The principles, framework, requirements and guidelines for Life Cycle Assessment are laid out in international standards ISO 14040I-3 and ISO 14044I-4.

Most major OEMs utilize some form of life cycle thinking or LCA, recognizing its importance and effectiveness in product and process design. Material producers also accept and use LCA. Together with many of their member companies, the trade associations of the steel, aluminium, and plastics industries are among the most active members of the global LCA community.

The European Union requires accounting for embedded lifecycle emissions. Following a phase-in period, there will be monetary penalties assessed against companies not providing this information. These requirements will drive OEMs to demand pertinent details from all of their material suppliers.

Environmental policies target achieving a total net reduction in emissions, including GHG (measured in carbon dioxide equivalents, or CO2e, that is a measure of all greenhouse gases attributable to a product that affect global warming potential. Thus, CO2e includes gases other than CO2.

Properly applied, LCA enables automakers to ensure that improvements in one phase are not offset by worse performance in another phase. This assessment of potential trade-offs is critical to environmental improvement. For example, if the increase in production emissions of a lightweight material is greater than the decrease in use phase emissions, vehicle light-weighting in this manner counter-productively increases total emissions.

LCA can be used to assess a broad array of environmental impacts beyond the global warming potential of greenhouse gases, including acidification, ecotoxicity, and ozone depletion.

The Path To Net Zero Emissions

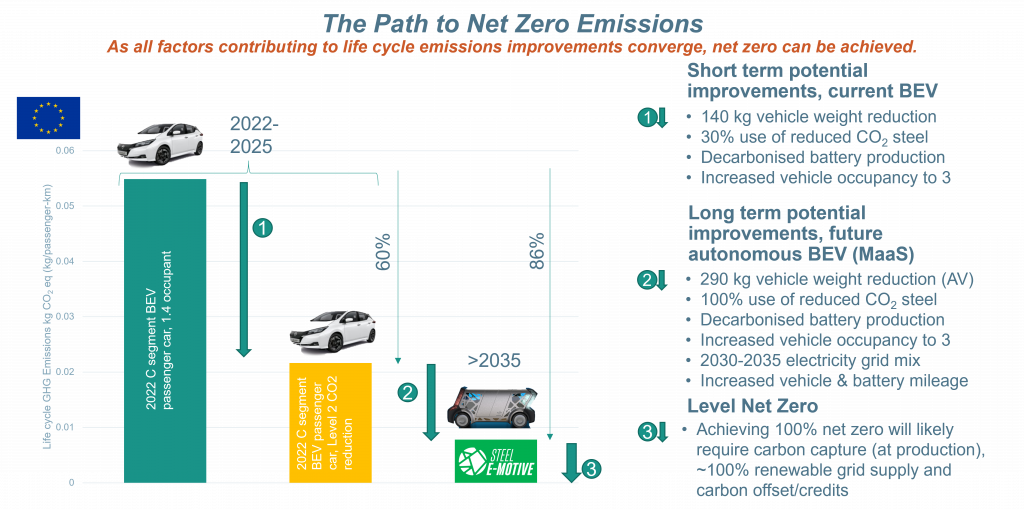

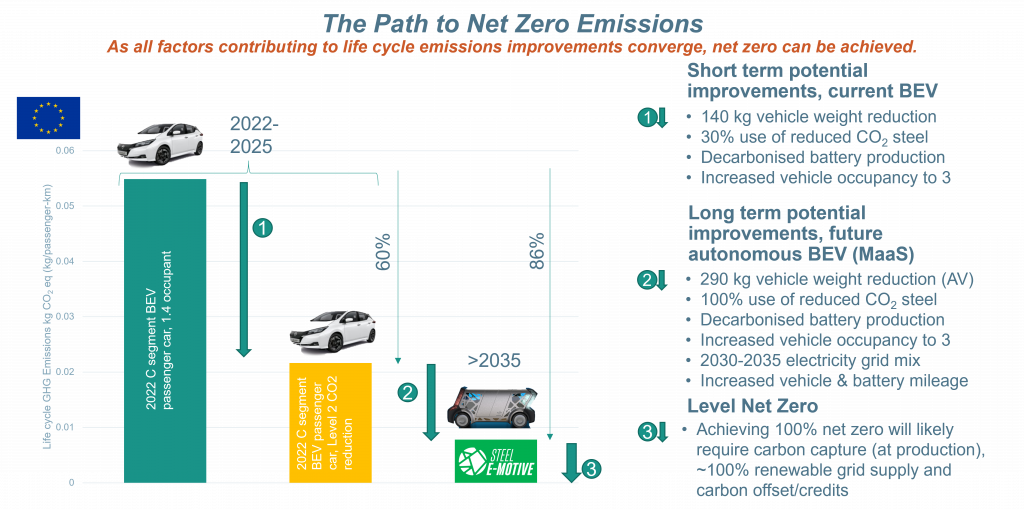

Fully autonomous Mobility as a Service vehicles such as the Steel E-Motive concept have the potential to address the ongoing and future requirements for decarbonisation of passenger transportation. Figure 4 shows the emissions walk-down beginning with a present-day C-sized BEV operating as a taxi.

Near term, a 60% reduction in Life Cycle emissions can be realized by an increased use of reduced CO2 steel and decarbonized battery production, along with an increased use of ride-sharing. Through 2035, as all available emissions reduction strategies are deployed – including autonomous MaaS vehicles with increased occupancy and extended vehicle and battery lives – an 86% reduction in emissions from a 2022 baseline is feasible.

Achieving Net Zero post 2035 requires carbon capture technologies, 100% renewable grid supplies, and carbon offsets or credits.

Each of these steps are described in detail within the Steel E-Motive Engineering Report.

Figure 4: The Path to Net Zero Vehicle Emissions

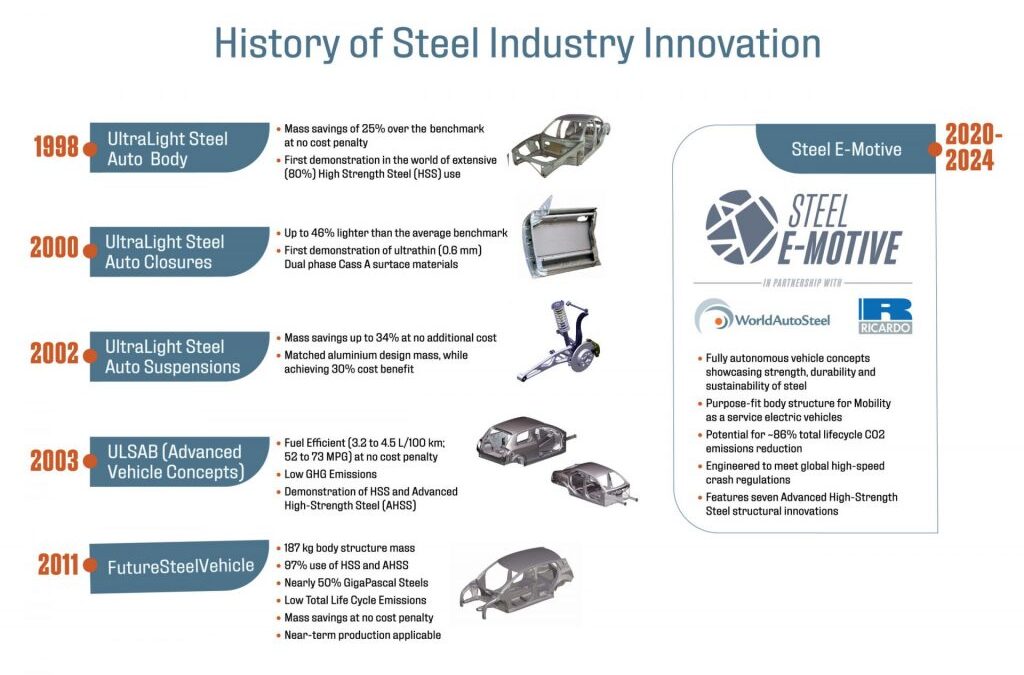

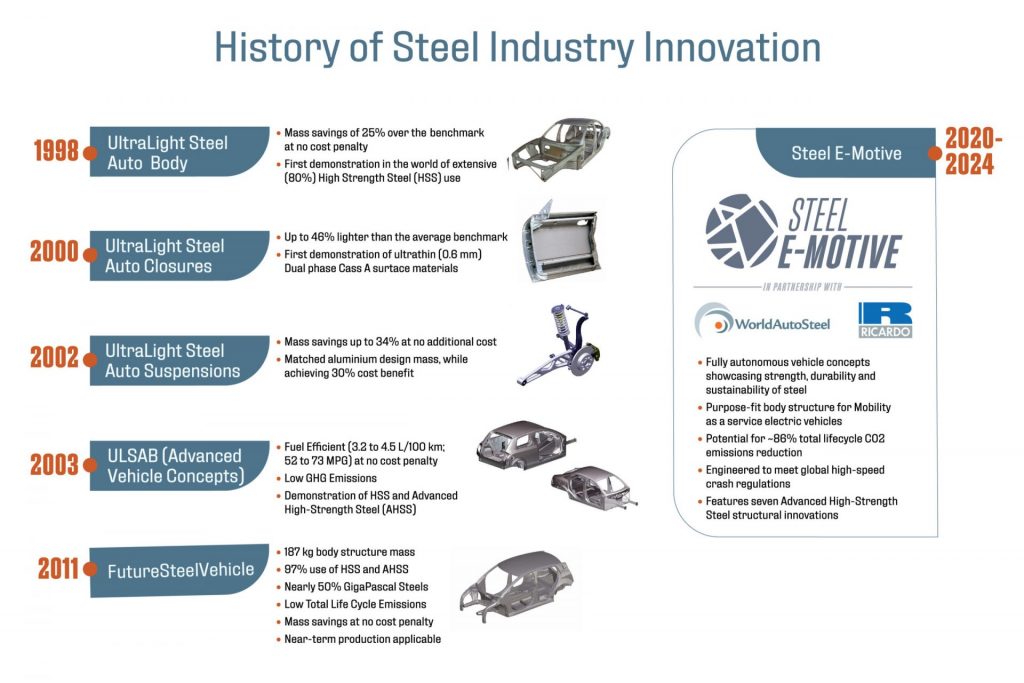

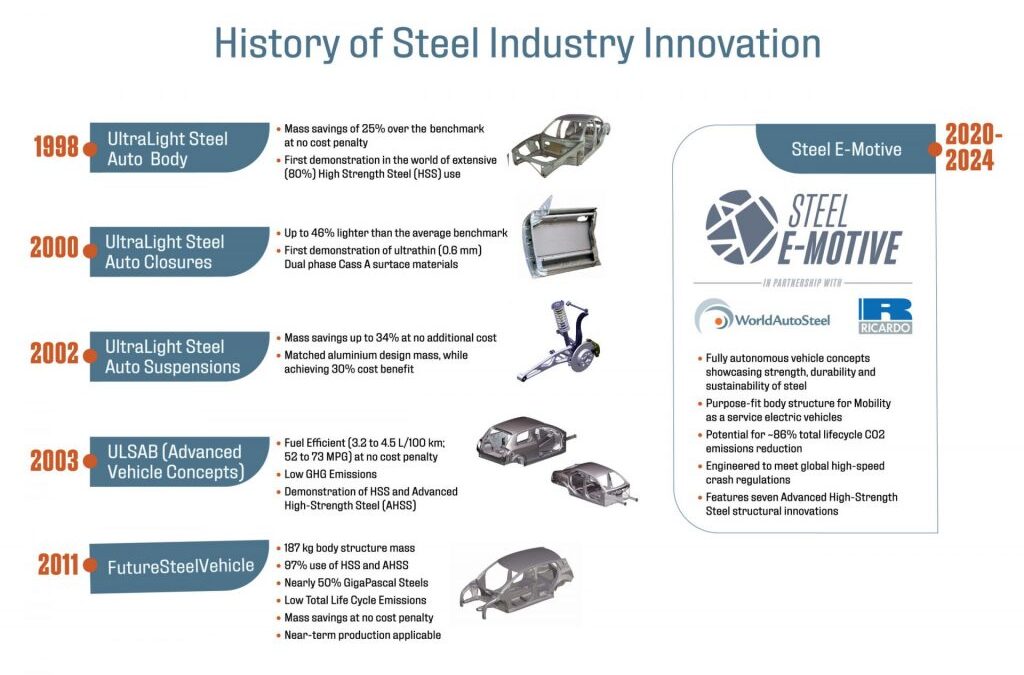

A consortium of 35 global sheet steel producers representing 22 countries began the UltraLight Steel Auto Body (ULSAB) program in 1994 with the goal of designing a lightweight steel auto body structure that would meet existing and proposed safety and performance targets.

The body-in-white (BIW) unveiled in 1998 validated the design concepts of the program, with the demonstration hardware achieving a 25 percent reduction of vehicle body structure weight at no cost penalty compared to conventional steel body structures of that time. ULSAB proved to be lightweight, structurally sound, safe, executable, and affordable.

ULSAB received wide acceptance by the automotive industry, to the point where is spawned three other steel consortia projects covering closures UltraLight Steel Auto Closures (ULSAC), suspensions UltraLight Steel Auto Suspensions (ULSAS) and full vehicle design UltraLight Steel Auto Body – Advanced Vehicle Concepts (ULSAB-AVC). Each one used an increasing percentage of high strength steels and Advanced High-Strength Steels (AHSS), along with advanced fabrication technologies such as tailored blanks, hydroformed tubes and continuous laser welding, each enhancing structural efficiency. At that time, AHSS use was in its infancy, and provided combinations of strength and ductility that were never-before realized, while still allowing for use of existing stamping and assembly fabrication equipment and production methods.

By 2008, the steel company consortium evolved into WorldAutoSteel, which began another program called FutureSteelVehicle (FSV), where steel members accelerated the development and deployment of new AHSS grades, further stretching the envelope for strength and ductility levels. FutureSteelVehicle took automotive steel applications to GigaPascal strength AHSS and added the dimension of designing for reduced life cycle emissions. W-11

FutureSteelVehicle featured clean-sheet steel body structure designs for advanced powertrains, including full battery electric vehicle (BEV), plug-in hybrid and hydrogen fuel cells – and demonstrated that sophisticated steel grades combined with engineering optimisation could reduce mass by more than 35 percent over a benchmark vehicle and reduced total life cycle emissions by nearly 70 percent. This was accomplished while meeting a broad list of global crash and durability requirements and enabled five-star safety ratings while avoiding high-cost penalties for mass reduction.W-11 More information about the FutureSteelVehicle is found here with greater details shown here: FutureSteelVehicle Reports

Steel E-Motive represents fully autonomous electric ride sharing vehicle concepts showcasing the strength and durability of steel with a critical focus on sustainability for reaching net zero emissions targets. The results are sustainable comfortable, safe and affordable body structures that support automakers in the continued development of Mobility as a Service (MaaS) ride sharing models. Some highlights of the Steel E-Motive program can be found here, with the entire program documented at https://SteelEMotive.world.

Another consortium, the Auto/Steel Partnership (A/SP) engages in research and demonstrates the value of AHSS through several programs. One such project, the Lightweight Front End Structure, used a holistic approach to meet goals of more than 20 percent weight reduction while maintaining crash worthiness.J-26 A-79 Manufacturability was examined and emphasized throughout this project. Another key program, the Future Generation Passenger Compartment project, examined the effect of mass compounding.A-80 U-15

Over the years since ULSAB, the successes of AHSS have motivated steel companies to continue research on both new types and grades of AHSS and to then bring these new steels to production. Essential for the growing use of AHSS has been the simultaneous development of new processes and equipment to produce and form the material. Some of these processes are described throughout these guidelines.

Figure 1: WorldAutoSteel Vehicle Development Programs.

Tailored Products

topofpage

Types of Tailored Products

Key materials characteristics for formed parts include strength, thickness, and corrosion protection. Tailored products provide opportunities to place these attributes where they are most needed for part function, and remove weight that does not contribute to part performance.

Welded Tailored Blanks (Tailor Welded Blanks)

Welded tailored blanks are a type of tailored product, as are patchwork blanks, tailor welded coils, tailor rolled coils, tailor rolled tubes and tailor welded tubes.

Laser welding is the most common approach to creating these products, but other options like resistance mash seam welding are possible. Mash seam welding requires that the blanks overlap, which adds mass. The heat affected zone (HAZ) for mash seam welds is considerably larger than that of laser welds. Compared with laser welding, the temperature reached when resistance mash seam welding is lower. This may improve formability due to reduced martensite formation, but the larger HAZ and thicker joint may negate this benefit. Non-linear welds are more challenging to produce with the mash seam approach. Welded Tailored Blanks refers to blanks made via either laser welding or mash seam welding. The following discussion centers on blanks and coils joined by lasers.

Butt-welding two or more flat sheets into a single blank creates a laser welded tailored blank (LWTB), also known as a tailor welded blank or laser welded blank (LWB). Steel grades and thickness may be (and usually are) different in the component sheets. Corrosion protection strategies may be different on each component of the welded blank. “Sub blanks” is another name for these component sheets.

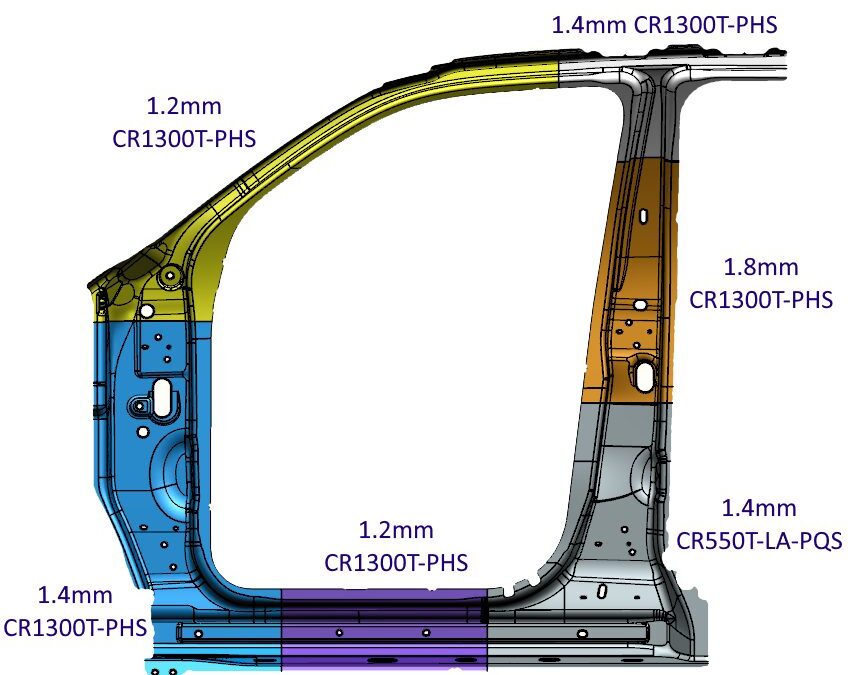

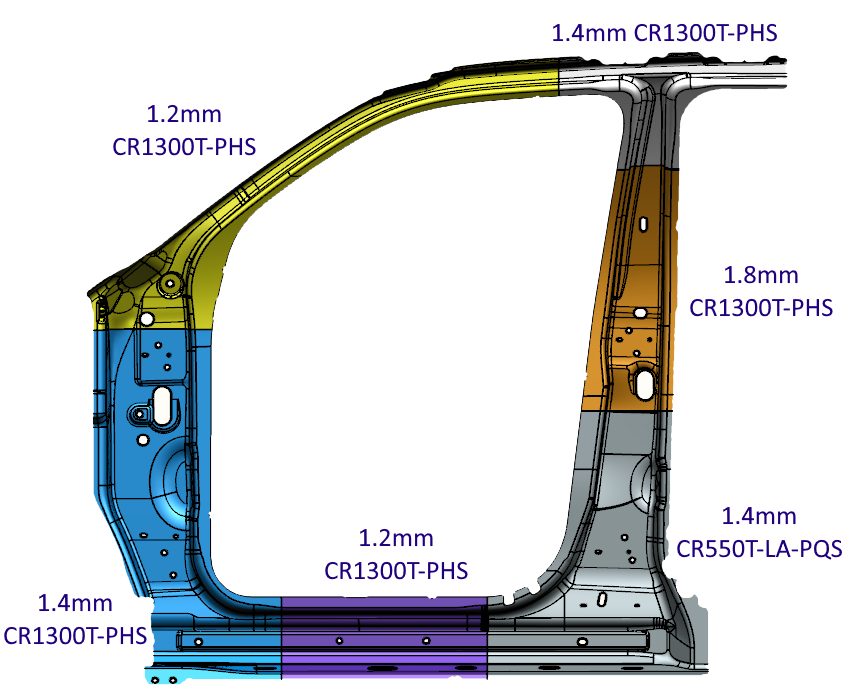

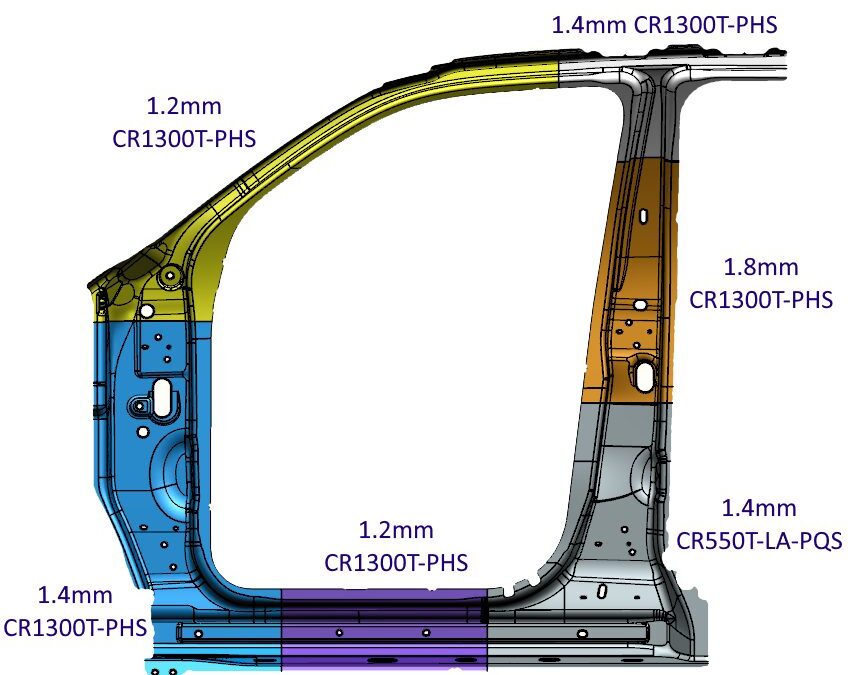

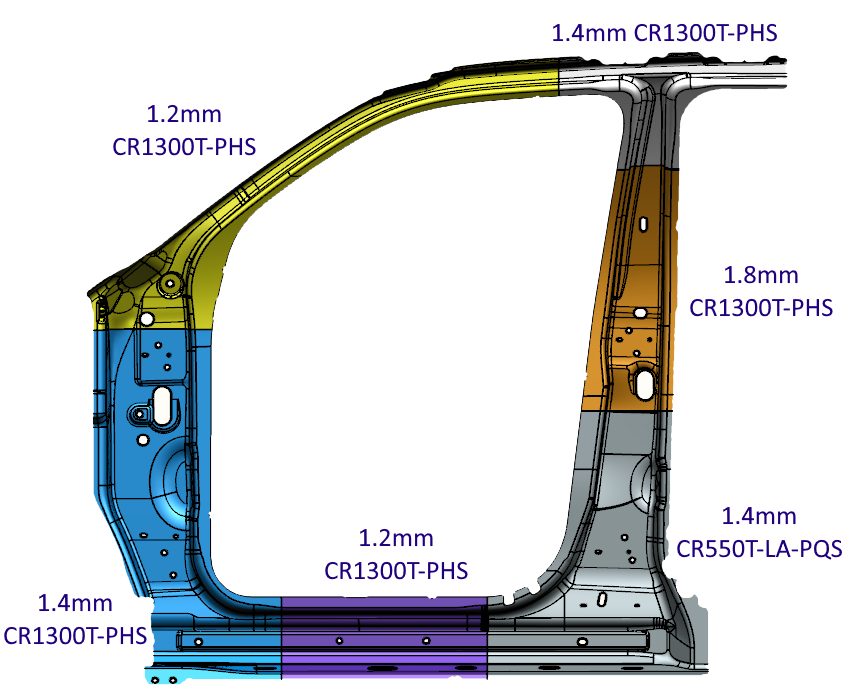

Figure 1 shows a laser welded door ring with multiple grades and thicknesses. This technology allows for a reduction in panel thickness in non-critical areas, thus contributing to an overall mass reduction of the part. The lower strength product in the bottom section of the B-Pillar helps dissipate the crash energy in the event of a side impact, playing a key role in crash energy management.

Figure 1: Six-piece Laser Welded Tailored Blank with multiple grades and thickness.R-3

Patchwork Blank

An alternate approach to a laser welded tailored blank involves the creation of what is known as a patchwork blank, consisting of two or more blanks potentially having different thickness or grades. The unique characteristic is that the blanks are placed one on top of the other and (typically) spot welded together while still flat. The patched blank requires only one stamping operation, eliminating the need to join them after forming the components separately. This approach is satisfactory for both cold stamping and hot stamping. The correct number of spot-welds is important in terms of cost and safety. Furthermore, if the components shift relative to one another during the forming operation, the spot welds may shear. There is excellent fit between both parts after forming, allowing for easy application of additional spot welds if needed. Part size, the number and location of reinforcements, and available infrastructure are among the key considerations in deciding between a laser welded or patch blank approach. For example, patchwork blanks may be preferred if the reinforced area is relatively small with complex contours or located within the boundaries of the main blank.

Tailor Welded Coils

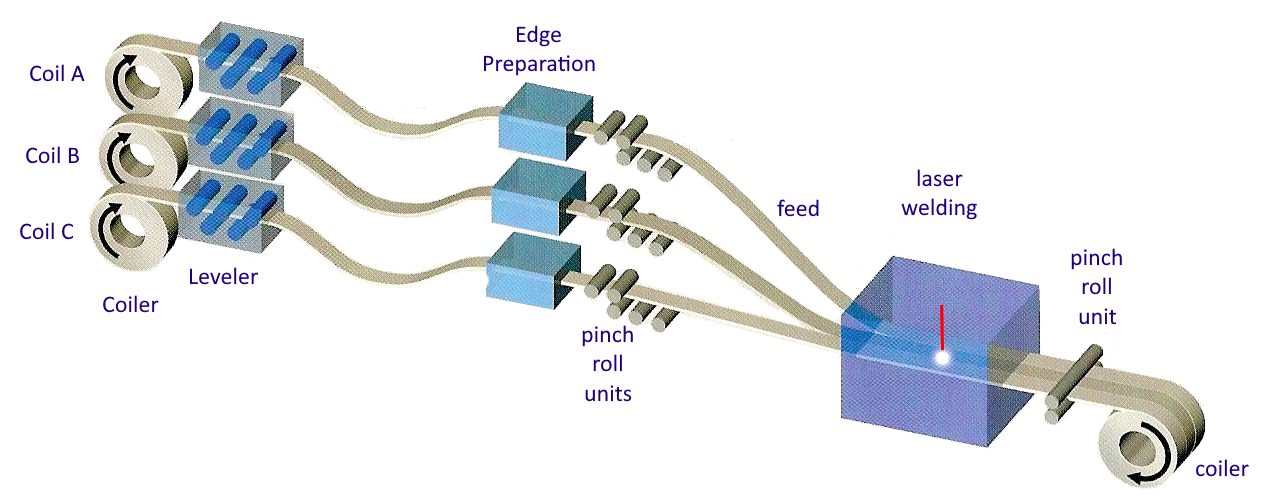

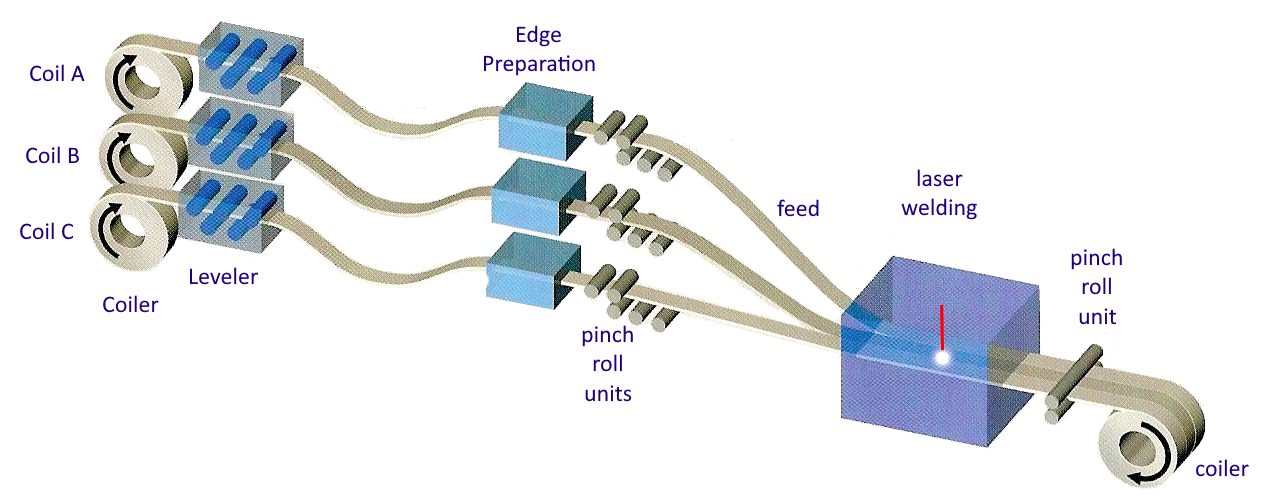

Rather than building blanks from individual components, a similar approach is to join entire coils together, edge to edge. These tailor welded coils (Figure 2) are used in coil-fed processes such as blanking, progressive die stamping, transfer press stamping, and roll forming operations. The basic process takes separate coils, prepares their edges for contiguous joining, and laser welds these together into one master coil. The new strip is either directly blanked or re-coiled for future blanking or use as feedstock for a continuous coil-fed stamping or roll forming line (Figure 3). Variations in strength, thickness, and coating occur across the width.

Figure 2: Production Process of Tailor Welded Coils.S-28

![Figure 3: General usage of Tailor Welded Coils [S-28]](https://ahssinsights.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/tailor-welded-cole-common-use.jpg)

Figure 3: General usage of Tailor Welded Coils.S-28

Tailor Rolled Coils

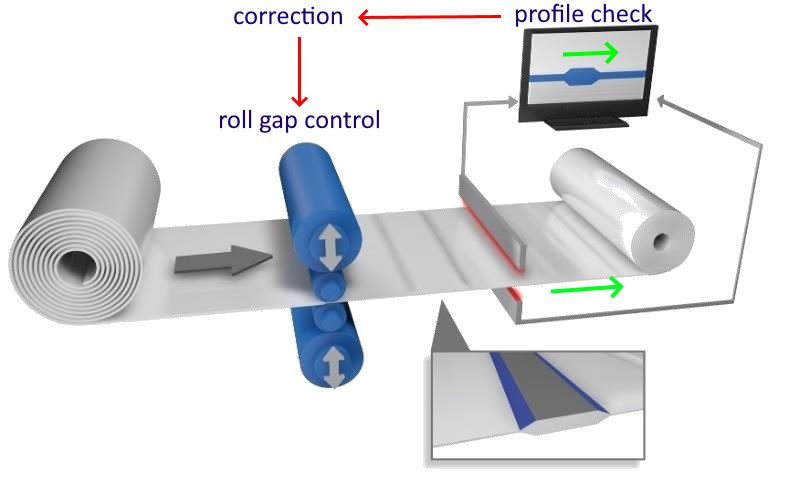

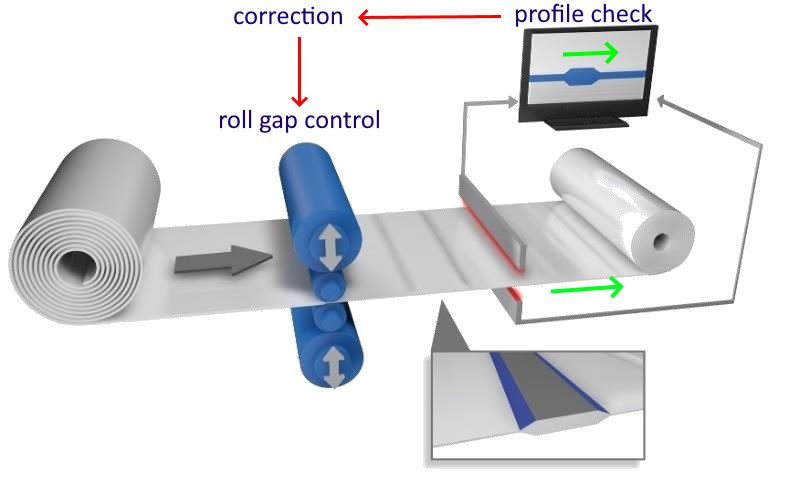

Whereas tailor welded coils can vary in properties across the coil width, tailor rolled coils have variable thickness down the length of the coil. Production facilities for tailor rolled coils vary the gap between the rolls used for thickness reduction, allowing for different strip thicknesses in the direction of rolling (Figure 4). Accurate measuring and feedback control technology guarantees the strip thickness tolerances. A significant advantage to this approach results from the transition from one thickness to another with no joints or discontinuities, providing an efficient load path without stress risers. A tailor rolled coil can be either used for blanking operations (for stamping or tubular blanks), or as feedstock into a roll forming line.

Figure 4: Tailor Rolled Coils vary in thickness down the length of the coil.Z-5

After cold rolling to achieve the targeted thickness variation, coils are annealed to reset the mechanical properties. Tensile properties can be uniform in the blank, with only the thickness varying. Tailored properties are generated by adjusting the incoming coil thickness and the associated thickness reductions, leading to different degrees of recrystallization occurring in the annealing step.Z-14 TRBs used in press hardening do not need to be annealed first, and tailored properties can be produced with the appropriate PHS process.

Tailor Rolled Tubes

Tailor rolled coils are the feedstock to produce variable thickness tailor rolled tubes.

Tailor Welded Tubes

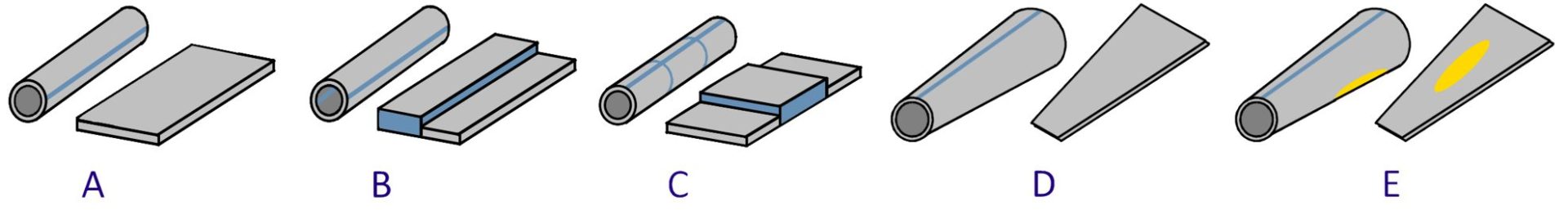

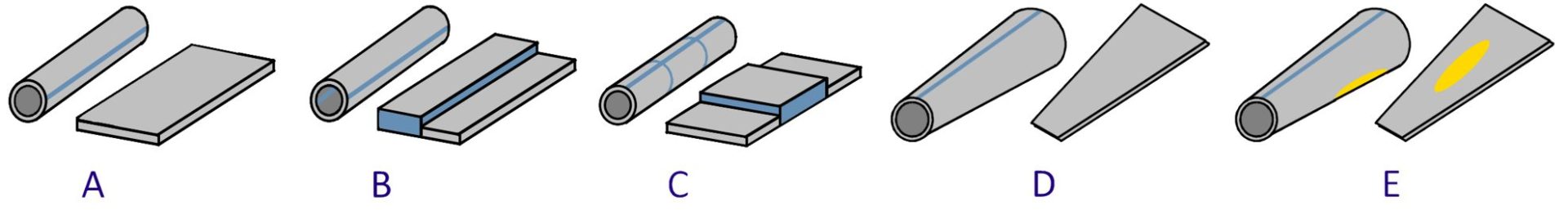

Conventional tube production involves roll forming strips to the desired shape and welding the free ends together to create a closed section. A tailor welded tube production process allows the designer to create complex variations in shape, thickness, strength, and coating (Figure 5)

Figure 5: Tailored tube production allows for differing thickness and strength within the same tube. A) 1-piece cylindrical tube with monolithic properties; B and C) 2-piece tailored tube with property variation down the length of the tube; D) 1-piece conical tube; E) 2-piece conical tube with a patchwork blank.

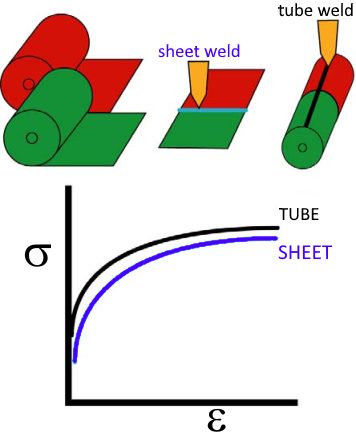

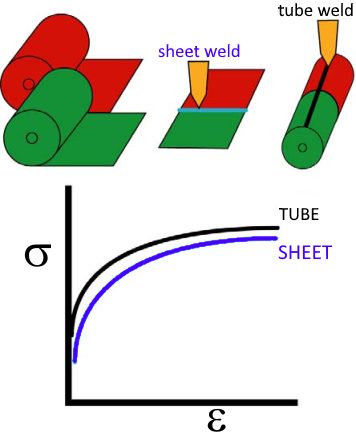

With hydroforming technology, the next step in tubular components is to bring the sheet metal into a shape closer to the design of the final component without losing tailored blank features (Figure 6).

Figure 6: Mechanical properties of tailored tubes are close to the original metal properties in the sheet condition. Hydroforming changes the properties based on the local deformation.G-8

Hydroformed conical tailored tubes offer automotive body engineers an additional approach to crash energy management while achieving a lightweight design. In frontal crash and side impacts the load paths have a key importance on the body design as they have a major bearing on the configuration of the structural members and joints. Figure 7 shows an example of a front-rail hydroformed prototype. The conical tailored tubes for this purpose take advantage of the high work hardening potential of TRIP steel.

Figure 7: Front-rail prototype based on a conical tube having 40 mm end to end difference in diameter.F-3

Another approach to create a tube with differential wall thickness is by ironing the inner surface.

One method to achieve this is to fix one end of the tube with a stopper, and expand that tube by pushing the punch (Figure 8) into the other end. Next, the stopper is removed and, with the part expanded in the first process engaged with the die, the punch is pushed in to iron the inner tube surface which reduces its wall thickness. The punch is pushed in until the length of the ironed part has reached the targeted value. Finally, the punch is retracted and removed. As a result of these forming processes, a tube with differential wall thickness consisting of a longitudinal expanded part (thick), ironed part (thin), and unprocessed part (thick) can be obtained.K-67 Among the factors contributing to forming success are the interaction of the punch design, including the length of the parallel section (LP) and semiangle (αP), and the clearance between the punch and die (CP). The length of the parallel section and the semiangle have been shown to have a significant effect on the forming load, but the clearance did not.K-67 The punch with larger LP, or the punch with smaller αP or smaller CP, results in improved formability. This happens because steel tube slipping does not occur even at small friction differences between the tube-punch and tube-die interfaces (Δµ) due to the forces being in equilibrium.K-67 Finite element modeling of these parameters, as well as experimental verification, can be found in this citation as well.

Figure 8: Punch shape to facilitate production of tailored tube, according to Citation K-67.

Benefits of Tailored Products in Automotive Body Construction

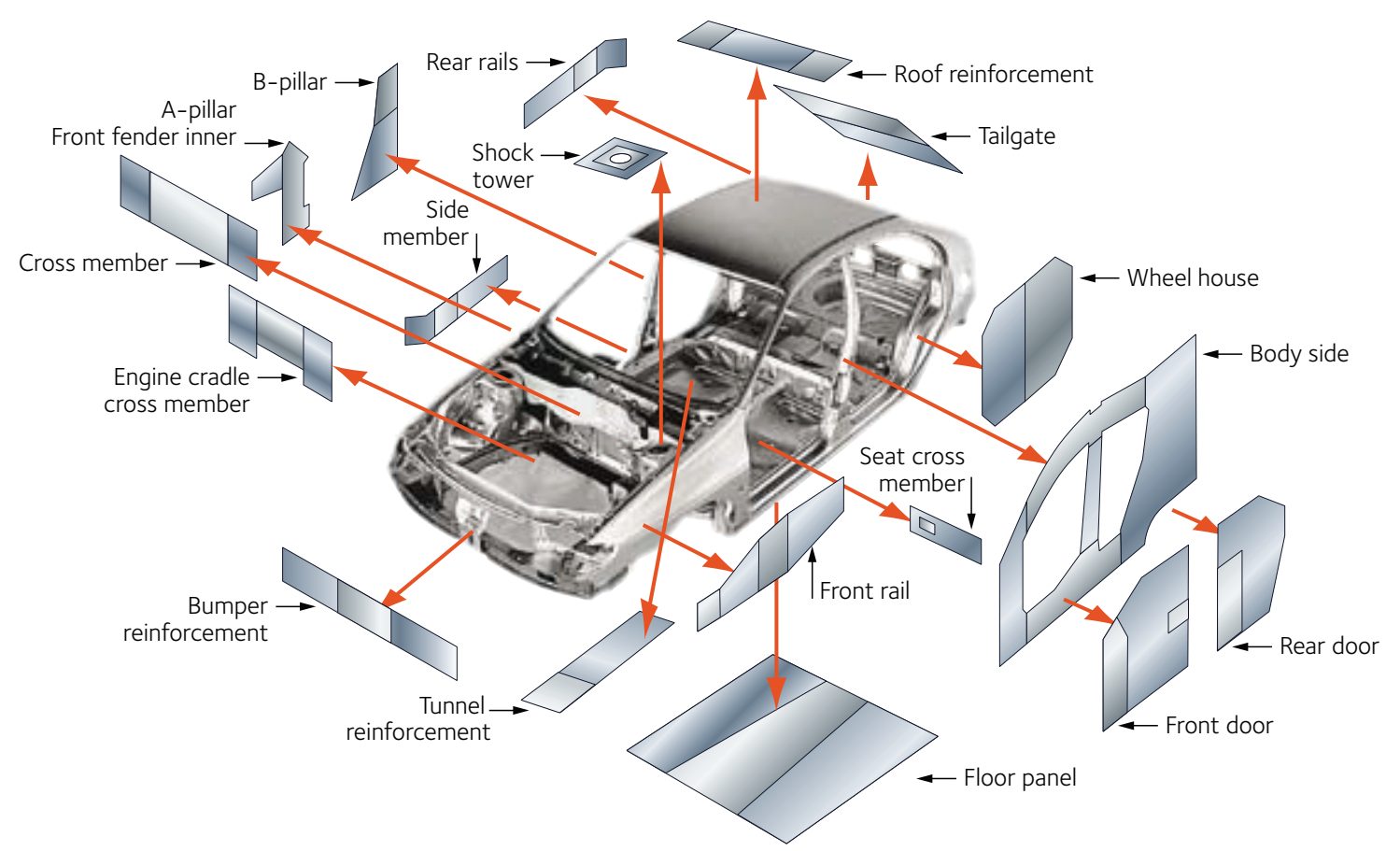

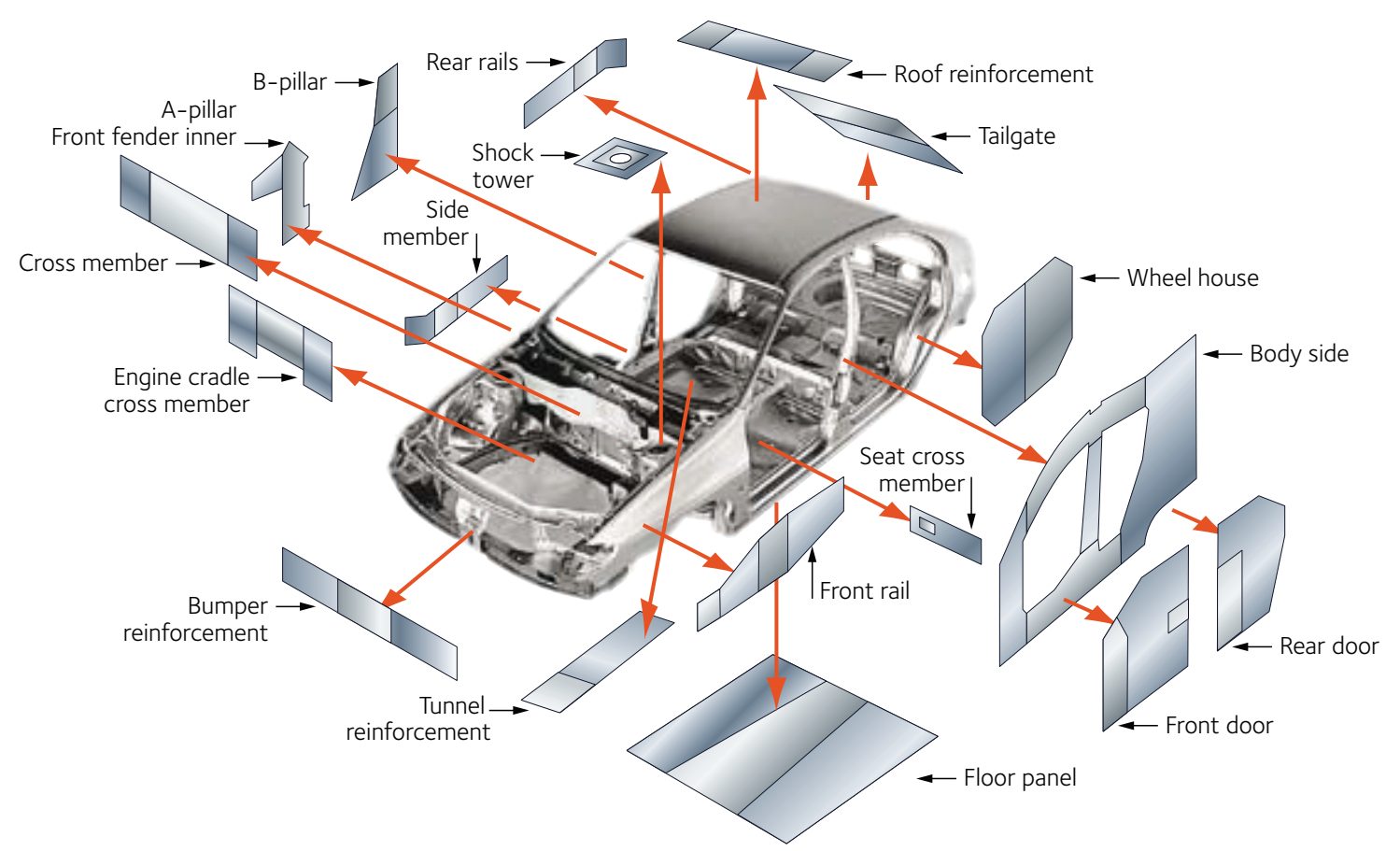

Figure 9 highlights some of the areas within the body structure where companies have considered transitioning to welded tailored blanks. Other tailored products may be suitable in other areas.

Figure 9: Applications suited for welded tailored blanks.A-31

Tailored products offer numerous advantages over the conventional approach involving the stamping and assembly of individual monolithic blanks which have a single grade, thickness, and coating, including:

Improved materials utilization

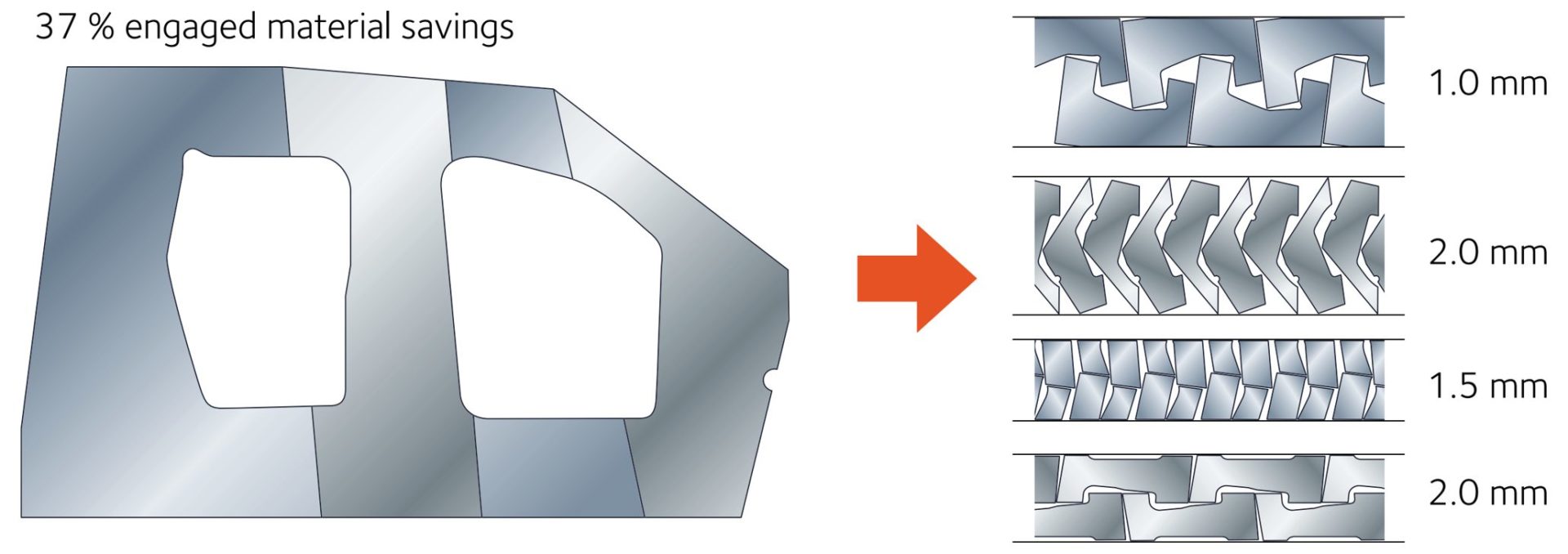

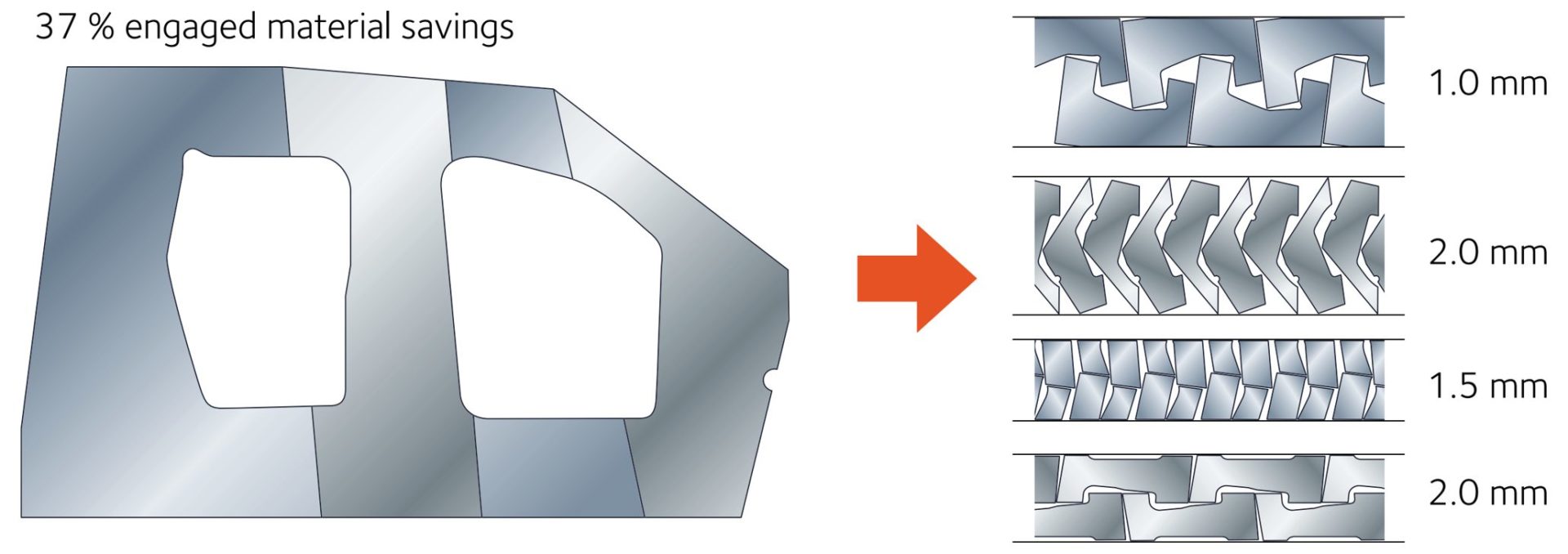

- Certain parts, like door rings (Figure 1), window frames, and door inner panels, have large cutout areas contributing to engineered scrap. Converting these to welded tailored blanks allows for optimized nesting of the individual components. Figure 10 presents an example of optimized nesting associated with body side aperture designs using a tailor welded blank. Reduced blank width requirements may allow for additional suppliers or use of master coils yielding slit mults. In the other extreme, blank dimensions larger than rolling mill capabilities are now feasible.

Elimination of reinforcement parts and reduced manufacturing infrastructure requirements

- In areas needing additional thickness for stiffness or crash performance, conventional approaches require stamping both the primary part and an additional smaller reinforcement and then spot welding the two parts together. The tailored product directly incorporates the required strength and thickness. Compared with a tailored product, the conventional approach requires twice the stamping time and dunnage, creates inventory, and adds the spot welding operation. Tolerance and fit-up issues appear when joining two formed parts, since their individual springback characteristics must be accommodated.

Part consolidation

- Similar to the benefits of eliminating reinforcements, tailored products may combine the function of what would otherwise be multiple distinct parts which would need to be joined.

Weight savings

- Conventional approaches to body-in-white construction requires individual parts to have flat weld flanges to facilitate spot welding. Combining multiple parts into a tailored product removes the need for weld flanges, and their associated weight.

Improved NVH, safety, and build quality

- Joining formed parts is more challenging than joining flat blanks first and then stamping. Tailored products have better dimensional integrity. Elimination of spot welds leads to a reduction in Noise, Vibration, and Harshness (NVH). A continuous weld line in tailored products means a more efficient load path.

Enhanced engineering flexibility

- Using tailored products provides the ability to add sectional strength in precise locations to optimize body structure performance.

Easily integrated with advanced manufacturing technologies for additional savings

- Tailored products incorporated into hot stamping or hydroforming applications magnify the advantages described here, and open up additional benefits.

Figure 10: Nesting optimization dramatically reduces engineered scrap.A-31

Design, Usage, and Troubleshooting Guidance

Edge Quality of Component Blanks Used to Create the Welded Blank

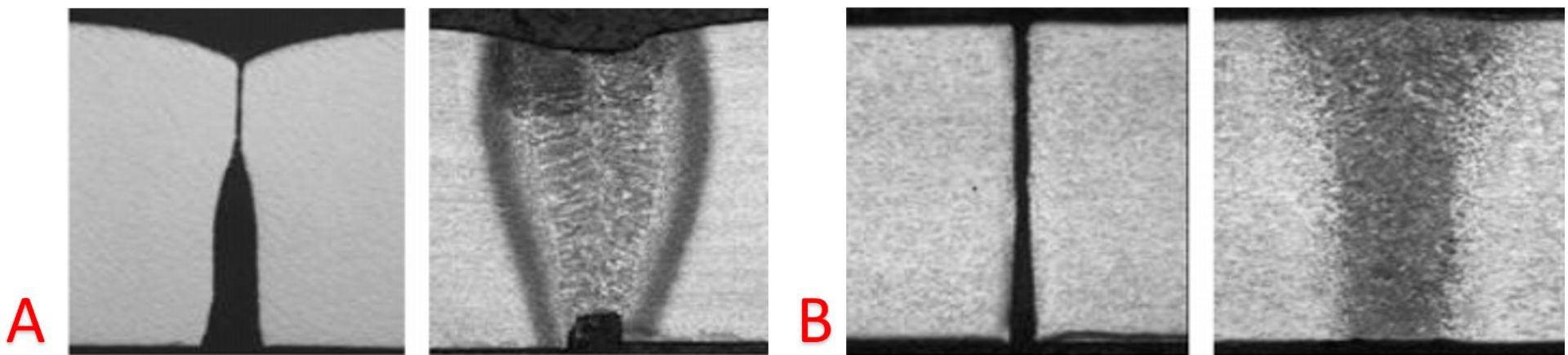

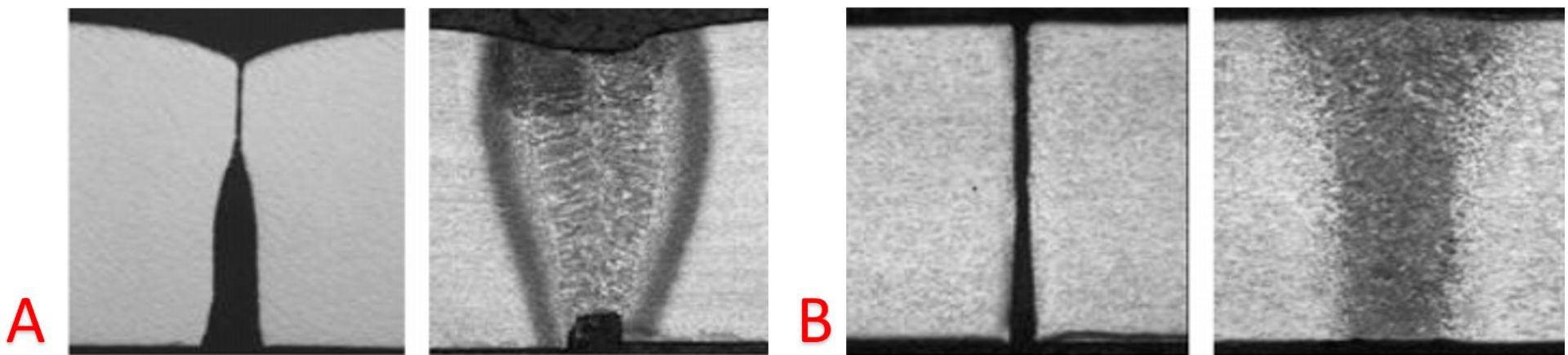

Minimal burr, maximized sheared edge stretchability, and maximized tool life are characteristics of good sheared edge quality in conventional blanking operations. When creating sub-blanks for assembly into a laser welded tailored blank, there is an additional critical characteristic: squared edges with high straightness are a prerequisite to avoid local gaps between the blank edges causing undercut in the weld bead and the associated loss of mechanical properties (Figure 11). Conventional shearing operations produce the edge seen in Figure 11a. Precision die blanking with tight clearances, as well as laser blanking, produce edges suitable for the blank welding operation (Figure 11b). Another option is to use a conventional shearing approach to produce a slightly oversize blank, and then use precision shears as the first step in the laser welding line. The advantage to this approach minimizes the impact of edge damage which might occur during transportation.

Figure 11: Edge condition and welding result. A) Poor edge resulting in increased residual butt gap and weld undercut; B) Optimum squared edge by precision die blanking or laser welding resulting in flush weld surfaces.S-29

Forming analysis of Welded Blanks

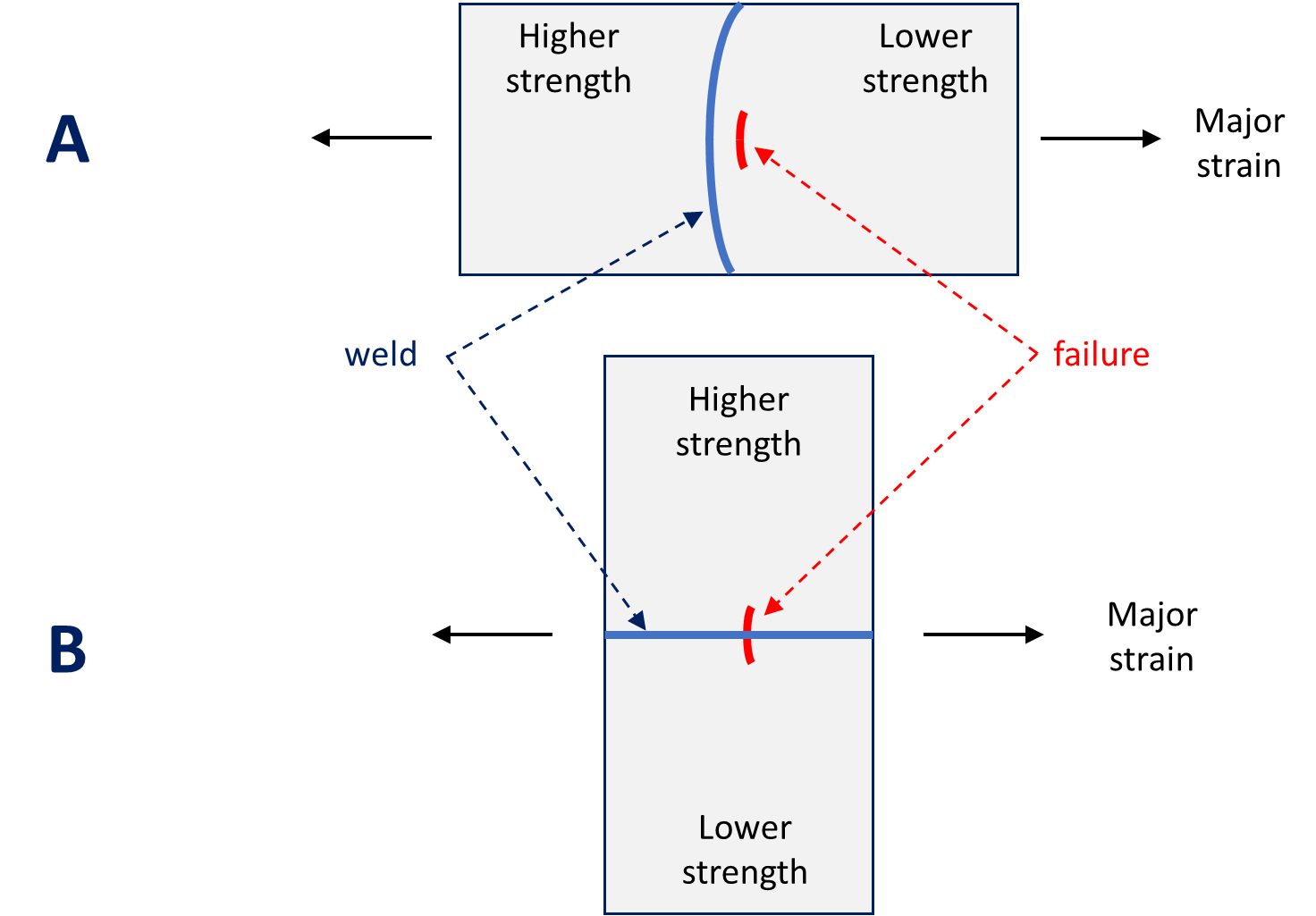

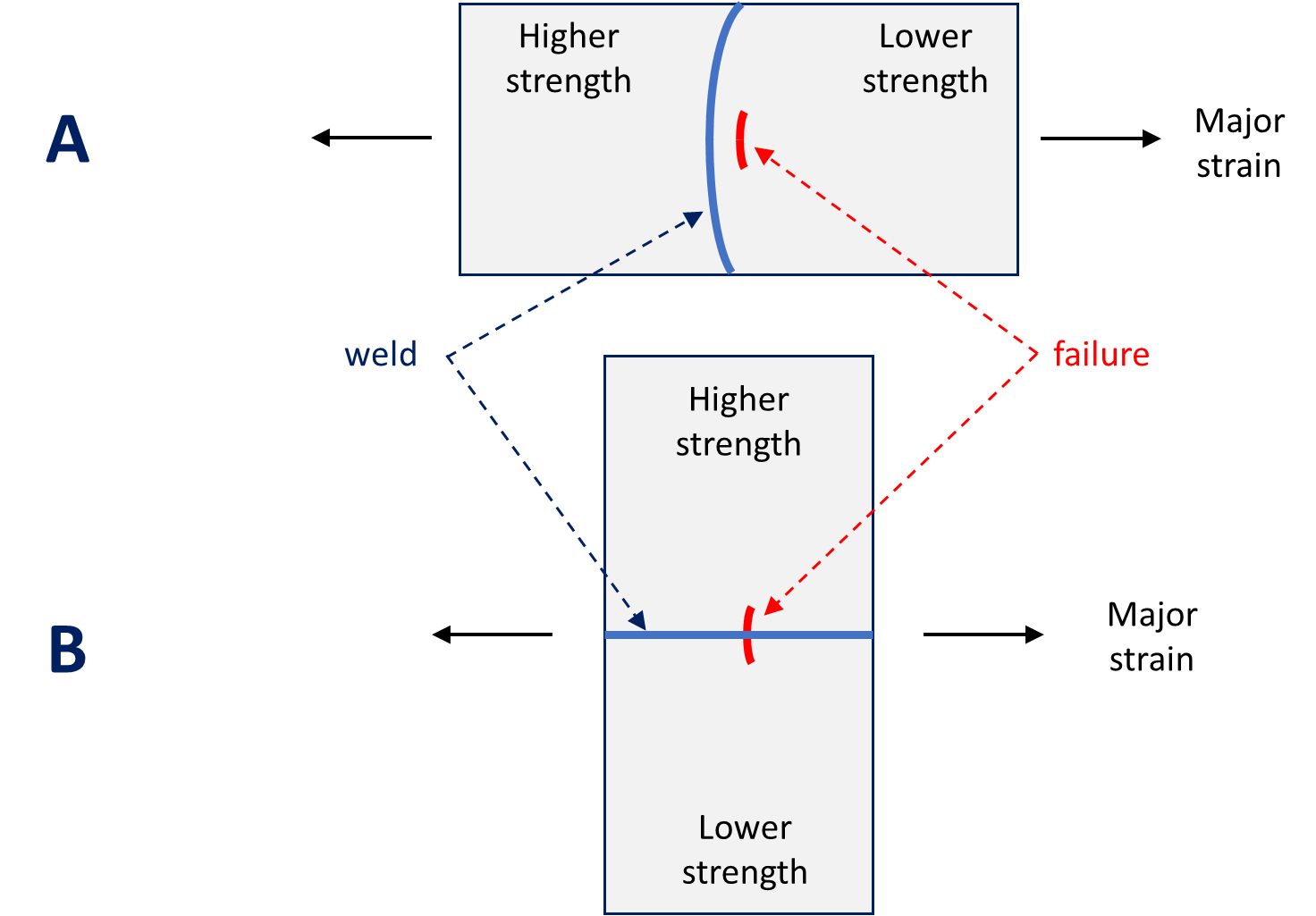

The weld joint and adjacent heat affected zone complicates the forming analysis of welded blanks. There are generally two scenarios that occur: failure perpendicular to the weld and failure parallel to the weld (Figure 12).

Figure 12: Major strain axis relative to weld line orientation. A) Weld line is perpendicular to the major strain axis; B) Weld line is parallel to the major strain axis.

Consider the scenario in Figure 12A, where the major strain is perpendicular to the weld line orientation. Failure occurs parallel to the weld in the lower strength, more ductile material. The restraining force provided by the higher strength material results in the weld line shifting towards that side.

With the weld seam moving towards the thicker and stronger metal, deformation occurs in thinner and weaker metal. The movement of the weld seam during stamping requires that a blankholder design with appropriate clearances so the welds can move through the blankholder during the drawing process. The punch-cavity clearances must allow for movement as well – otherwise a pinch-point is created and metal flow stops. These clearances are necessary for movement of the heavier gauge metal and the welds, but can also be a source of wrinkling on the lighter gauge side due to the lack of hold-down force in this area. Also, the potential exists for die wear in the locations in contact with weld seam. To counter the weld line motion to the higher strength side, consider allowing greater material flow from that side of the weld through a less severe draw bead design, reduced blankholder pressure or modified blank outline. These strategies help minimize the risk of this type of split.

Now consider the scenario in Figure 12B, where the major strain is parallel to the weld line orientation. Here, fracture occurs perpendicular to the weld line – typically within the weld itself – due to the poorer mechanical properties of the weld with respect to the base material. To avoid splits in the weld, orient the weld away from the major strain direction and away from areas with high strain concentration.

Use of Advanced High Strength Steels in Laser Welded Tailored Products

As sub-blanks are welded together to create the main blank, the beginning or ending of each of the weld lines are not in a steady state condition. As such, the start or stop action of the welding may create a stress riser. After the main blank is built-up, a scalloped cut can remove the affected areas so that only sections of uniform edge quality are formed in subsequent operations.

Laser welding is a high energy density process that focuses the heat in a very localized region as the laser travels at a high speed. This results in a narrow heat affected zone and the rapid quenching leads to the formation of a high-hardness martensite. Increased welding speeds generally require higher energy intensity at the weld which increases peak hardness.

Different welding parameters must be used for advanced high strength steels due to the presence of martensite in the base metal. The microstructure in the heat affected zone is a function of the local time/temperature profile, which changes with distance away from the weld as well as with the composition of the alloy in question. Laser welding some AHSS grades results in tempered martensite in the heat affected zone, leading to a locally softened region. Crash modeling should incorporate the influence of the softened region, which may help dissipate a portion of the crash energy.

However, this softened region creates an area for high strain concentration, leading to premature failure in martensite-containing AHSS grades. Higher strength dual phase steels have more martensite than lower strength dual phase grades, and therefore are more likely to generate HAZ soft zones and reduced formability when used in laser welded blanks. CP and TRIP steels have a lower incidence of HAZ soft zones due to higher alloying content. More information about laser welding is found here.

Blank Stacking, Destacking, and Feeding Problems

Depending on the thickness differences between the component blanks and their relative sizes, embossed dimples on the thinner gauge side can balance the thickness difference and to allow stable coil winding (in the case of tailor welded coil production) or stacking as they are blanked onto a lift. The stack weight and banding of the pallets may contribute to collapsing the dimples, so some companies choose to minimize the stack height.

Automatic destackers and feeders typically require uniform blanks and stacks for trouble-free operation. Dimples and cutouts may interfere with proper operation of overhead vacuum cups or magnetic belts. Moving or deactivating Vacuum cups may be necessary. Dimples should either be outside of the magnetic belt area or have their form away from the belt. Dimples may be a problem for some in-line blank washers and die-lube roll coaters.

Press and Tooling Considerations

When there is a large thickness difference within the component blanks, press tonnage and balance can be a problem. Press tonnage monitors are essential for this type of part, not only for protection of the press equipment, but also for good process control. If press balance is a problem, the tonnage monitors will indicate where the problem is. Supplemental balance devices in the die, such as nitrogen cylinders, may be appropriate, or the stamping may need to move to a larger press.

Tailored products often contain sub-blanks of mixed strength and thickness. The chosen die process must reflect those differences, and account for changes in side-wall curl, springback and drawability characteristics across the part. Mild steel can usually be formed with high strength steel die processes, but high strength steel will not always form satisfactorily with conventional die processes used with mild steels.

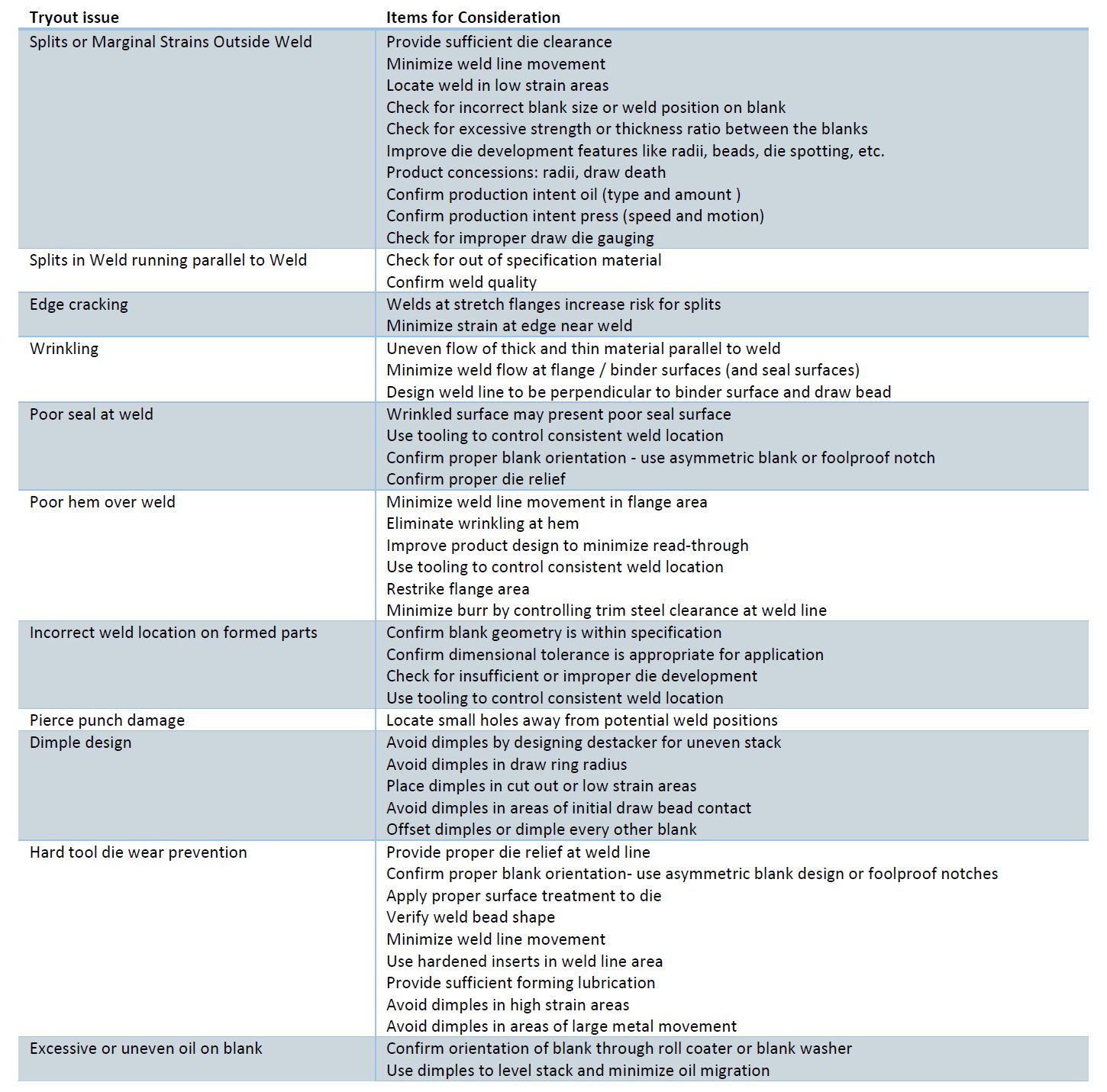

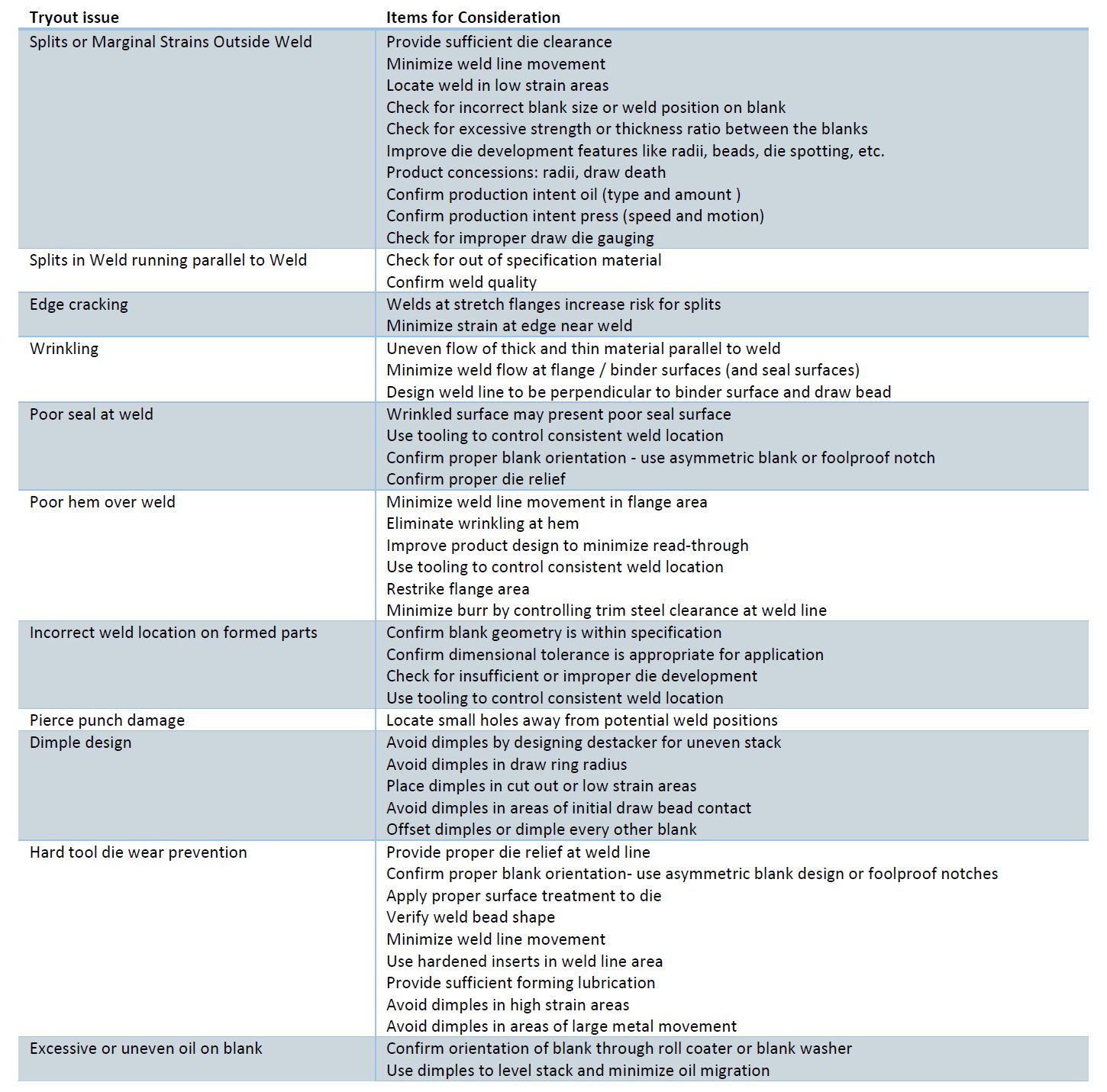

Tailor Welded Blanks Stamping Tryout Issues Checklist.A-20

Case Study: Deploying Tailored Blanks in Electric Vehicles

Many thanks to Isaac Luther, TWB Company, for providing this case study.

Laser-welded blanks (LWBs) allow the combination of different steel grades, thicknesses, and even coating types into a single blank. This results in stamping a single component with the right material in the right place for on-vehicle requirements. This technology allows the consolidation of multiple stampings into a single component.

One example is the front door inner. A two-piece design will have an inner panel and a reinforcement in the hinge area. As shown in Figure 13, a laser welded front door inner incorporates a thicker front section in the hinge area and a thinner rear section for the inner panel, providing on-vehicle mass savings. This eliminates the need for additional components, reducing the tooling investment in the program. This also simplifies the assembly process, eliminating the need to spot weld a reinforcement onto the panel.

Figure 13: Front Door Inner Stamped from a Laser Welded Blank

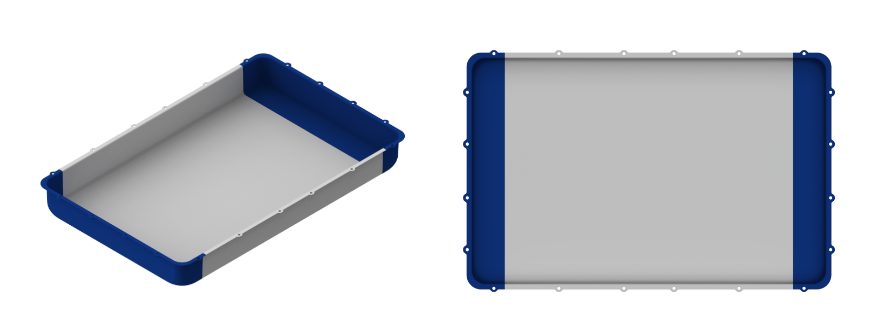

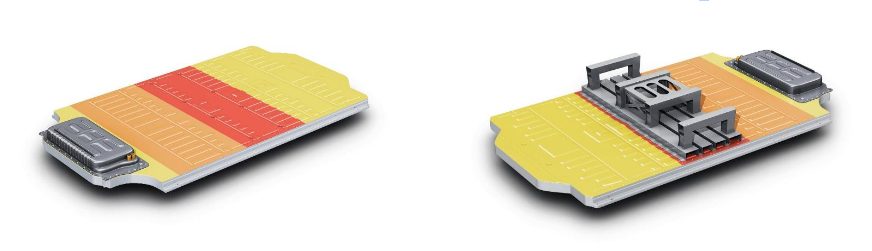

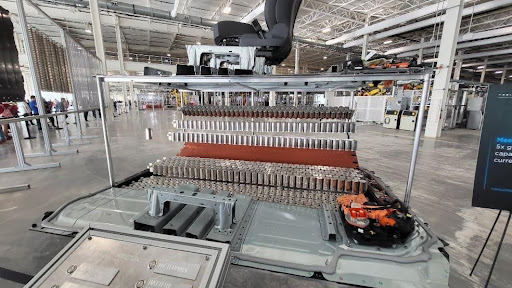

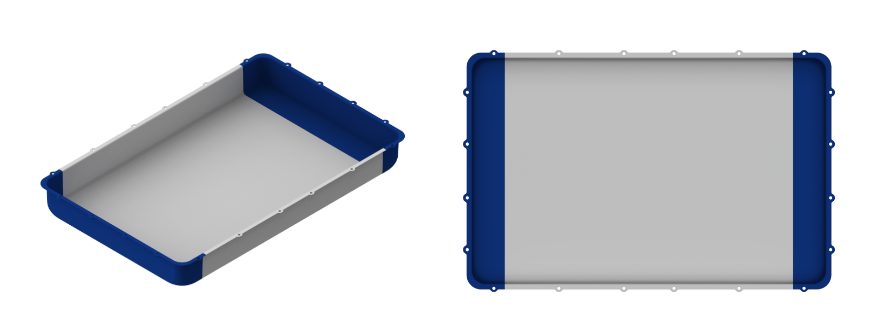

Today, large opportunities exist to consolidate components in a BEV in the battery structure. Design strategies vary from different automakers, including how the enclosure is constructed or how the battery mounts into the vehicle. The battery tray can have over 100 stamped components, including sealing surfaces, structural members, and reinforcementsM-68. As an idea, a battery tray perimeter could be eight pieces, four lateral and longitudinal members, and four corners. The upper and lower covers are two additional stamped components, for a total of ten stampings that make up the sealing structure of the battery tray. On a large BEV truck, that results in over 17m of external sealing surfaces.

Part consolidation in the battery structure provides cost savings in material requirements and reduced investment in required tooling. Another benefit of assembly simplification is improved quality. Fewer components mean fewer sealing surfaces, resulting in less rework in the assembly process, where every battery tray is leak-tested.

The deep-drawn battery tub is a consolidated lower battery enclosure and perimeter. This can be seen in Figure 14; a three-piece welded blank incorporates a thicker and highly formable material at the ends and in the center section, either a martensitic steel for intrusion protection or a low-cost mild steel. This one-piece deep-drawn tub reduces the number of stampings and sealing surfaces, resulting in a more optimized and efficient design when considered against a multi-piece assembly. In the previous example of a BEV truck, the deep-drawn battery tub would reduce the external sealing surface distance by 40%. To validate this concept, component level simulations of crash, intrusion, and formability were conducted. As well as a physical prototype built that was used for leak and thermal testing Y-14 with the outcomes proving the validity of this concept, as well as developing preliminary design guidelines. Additional work is underway to increase the depth of the draw while minimizing the draft angle on the tub stamping.

Figure 14: Deep Battery Tub Stamped from a Laser Welded Blank

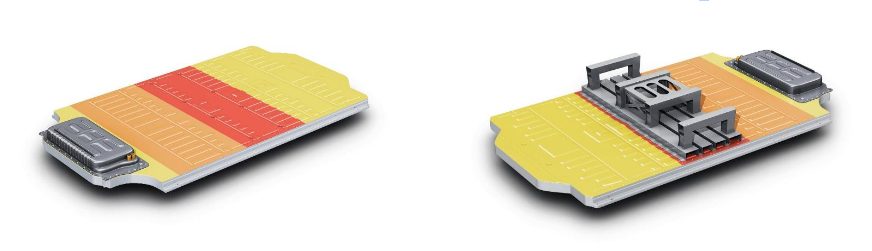

In most BEVs today, the passenger compartment has a floor structure common in an ICE vehicle. However, the BEV also has a top cover on the battery assembly that, in most cases, is the same size as the passenger compartment floor. In execution of part consolidation, the body floor and battery top cover effectively seal the same opening and can be consolidated into one component. An example is shown below, where seat reinforcements found on the vehicle floor are integrated into the battery top cover, and the traditional floor of the vehicle is removed. Advanced high-strength steels are used in different grades and thicknesses. Figure 15 show what the laser welded battery top cover looks like on the assembly.

Figure 15: Battery Top Cover from a Laser Welded Blank

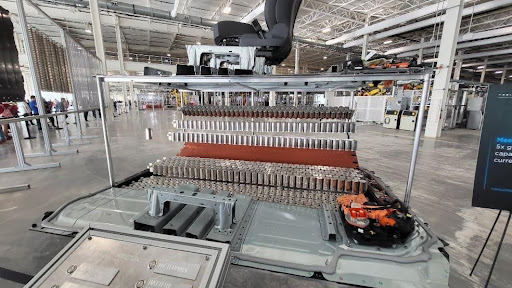

Vehicle assembly can also be radically simplified as front seats are mounted on the battery before being installed in the vehicle as shown in Figure 16, the ergonomics of the assembly operation are improved by increased access inside the passenger compartment through the open floor.

Figure 16: Ergonomics of the Assembly Operation

Cost mitigation is more important than ever before, with reductions in piece cost and investment and assembly costs being important. At the foundation BEVs currently have cost challenges in comparison to their ICE counterparts, however the optimization potential for the architecture remains high, specifically in part consolidation. Unique concepts such as using laser welded blanks for deep-drawn battery tubs and integrated floor/battery top covers are novel approaches to improve challenges faced with existing BEV designs. Laser welded blank applications throughout the body in white and closures remain relevant in BEVs, providing further part consolidation opportunities.

Thanks go to Isaac Luther for his contribution of this case study. Luther is a senior product engineer on the new product development team at TWB Company. TWB Company provides tailor-welded solutions in North America. In this role, Isaac is responsible for application development in vehicle body and frame applications and battery systems. Isaac has a Bachelor of Science in welding engineering from The Ohio State University.

Back to the Top

![Figure 3: General usage of Tailor Welded Coils [S-28]](https://ahssinsights.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/tailor-welded-cole-common-use.jpg)