About

WorldAutoSteel will consider appropriate articles from expert sources for publication on our AHSS Insights blog. In order to be considered, you must meet the requirements set forth below. Please keep in mind, however, that we do not pay for, or charge for, posting guest blogs. But we are more than willing to consider articles that are relevant to educating on best practices and new processes in the forming and joining of Advanced High-Strength Steels (AHSS) in vehicle applications.

If you still have questions about being a Guest Blogger for WorldAutoSteel after reading this page, you may contact the AHSS Guidelines Editor, Lori Jo Vest

Fundamentals

Please keep in mind the following fundamentals before you start writing your blog.

- Your submission must contain references to Advanced High-Strength Steel (AHSS) in vehicle applications. Note that the name of our blog is AHSS Insights, therefore, readers will be expecting to expand their AHSS knowledge base.

- Your submission must be geared towards a technical audience, with appropriate data references. Our audiences include automotive engineers that specialize in design, materials, manufacturing and the environment. We generally do not accept thought-starter type guest blogs.

- Your submission must not be a marketing piece for your organization, proprietary products or services, nor should it contain marketing messages and solicitations. Our readers are smart people. They will appreciate and gain much more insight into your company by simply demonstrating your expertise and showing your products’ purpose in AHSS use, than they would in a sales pitch.

- It should contain information pertinent to our audiences on an aspect of AHSS, such as AHSS characteristics, use, metallurgy, forming or joining. It also may address vehicle or steel industry life cycle assessment or other environmental issues related to automotive and AHSS use.

- Your submission must include graphic references. You may decide what kind of graphics you would like to add such as charts, videos, infographics, etc. We welcome videos as long as they do not include a sales pitch. Graphics need to be submitted as PNG or SVG files, and videos must be a standard format, such as MP4 or WMV.

Submission Requirements

Please meet the following submission requirements before you submit your entry for consideration.

- Submissions should be approximately 1,000 words in length, and include graphics.

- Please include a title.

- Graphics should be provided as separate 72 dpi (PNG or SVG) files, if possible, and sourced appropriately, especially if you do not specifically own the rights. Videos should be 720p resolution.

- Please clearly provide any reference sources in the following format: Author, full title of the work, year published, and if available and it will add to the blog’s content value, provide an internet link to the work.

- Please notify us with your intention to submit with an brief abstract of the information you will cover. This will help us determine if it is a good fit and enable us to potentially provide provisional approval.

- Your first draft must be submitted a minimum of 30 business days prior to any agreed upon publish date. This allows our team to have ample time for review, give you feedback and pursue any required further editing. It also provides time for translation to our Chinese blog edition.

- As your blog will be translated to the Chinese language and published on our channels in China, please do not use English jargon that will be difficult to translate.

We will notify you in advance as to when your entry is scheduled to publish. We strongly encourage you to use your social contact network to share the blog article. Your shares should include our blog hashtag, #AHSSblog.

Submitting Video and Animation Assets

We are always looking for video and animations to help support existing articles with visual information. If you think you have something that would enhance an article, please contact us at the email link above. You can send us a link to what you have, and we will review it. Note, the video must be owned by you in order to be considered and not contain any sales pitches. If we agree to use it, we’ll need to receive the original video file so that it can be uploaded directly to our site. You/your company will receive full citation as a the source of the video. Have a look at our Roll Forming page to see an example of how we have used a video received from Shape Corp.

We look forward to receiving your submission. It is our pleasure to collaborate on AHSS education with you. Thank you!

Blog, main-blog

A New Software Application for Thin Wall Section Analysis

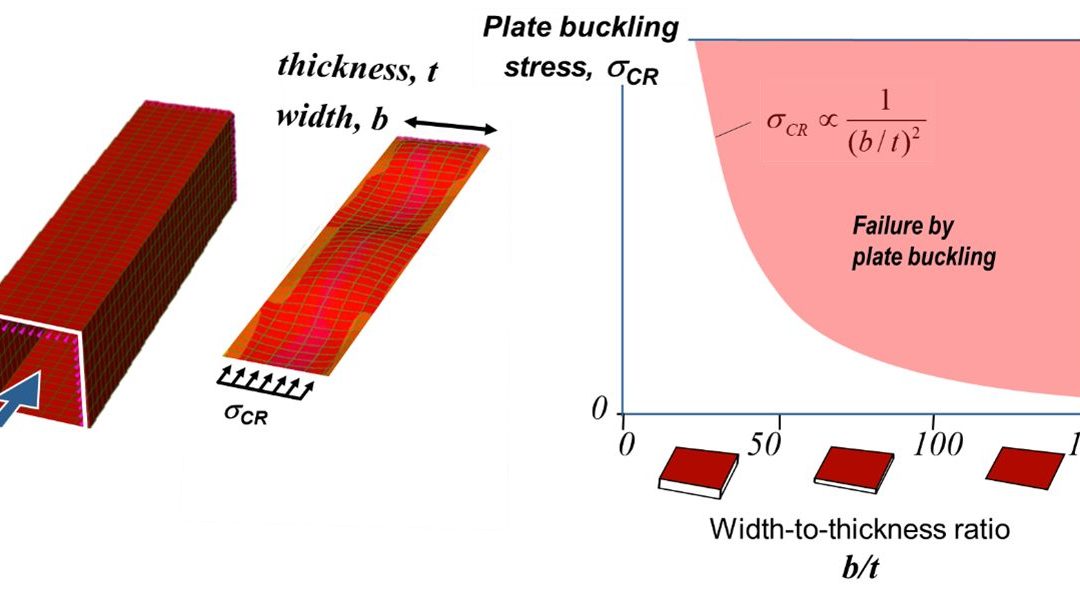

Advanced High-Strength Steel (AHSS) grades offer increased performance in yield and tensile strength. However, to fully utilize this increased strength, automotive beam sections must be designed carefully to avoid buckling of the plate elements in the section. A new software application, Geometric Analysis of Sections—GAS2.0, available through the American Iron and Steel Institute, is a tool to aid in this design effort.

Plate Buckling in Automotive Sections

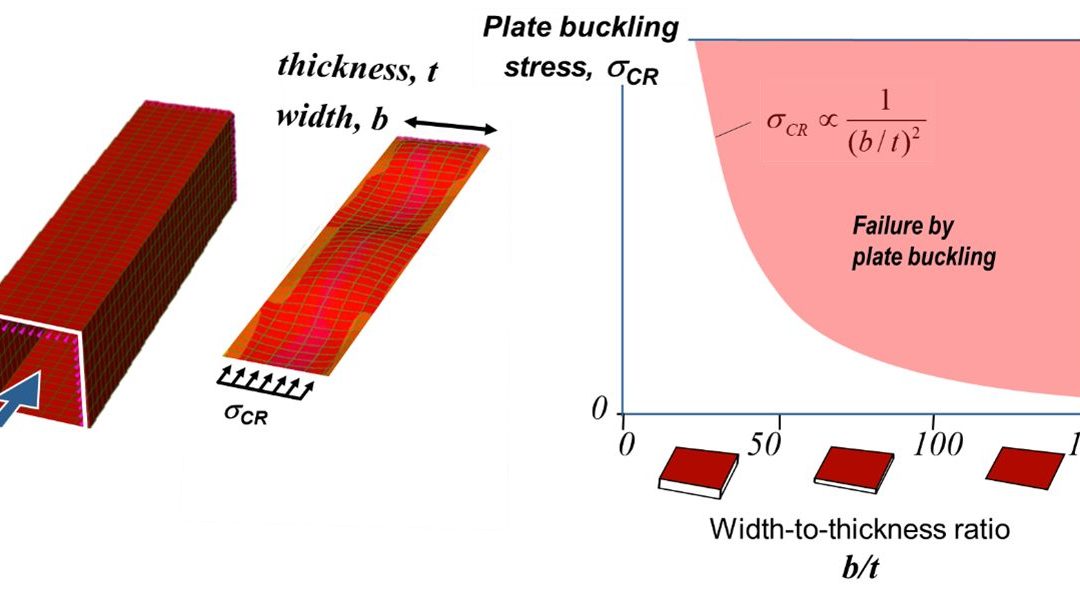

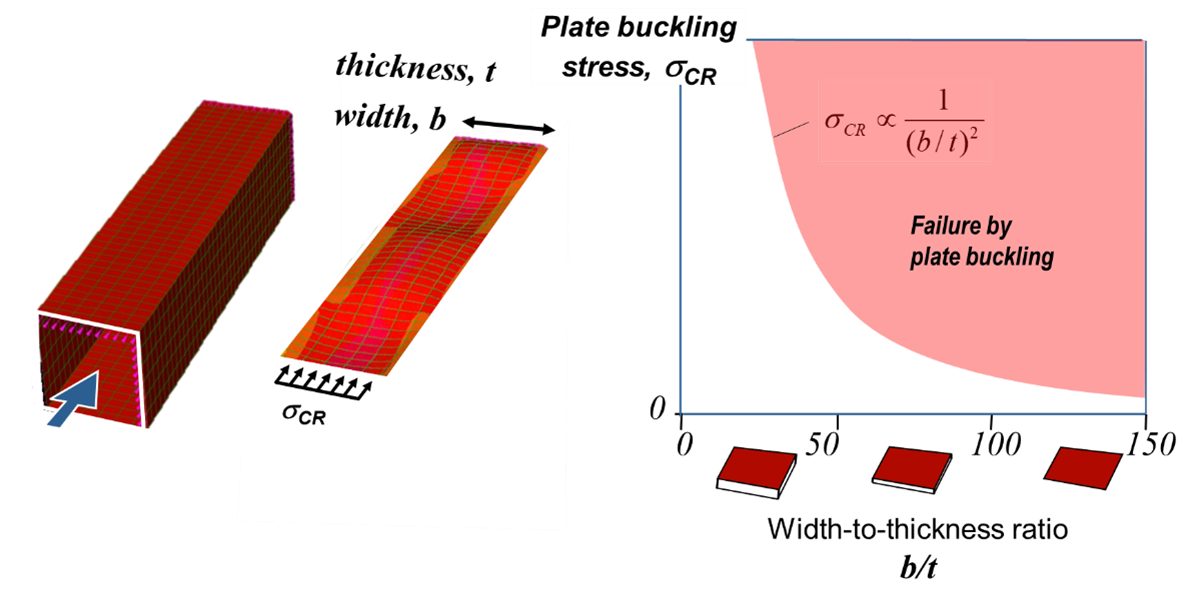

To understand how plate buckling affects the strength of a thin walled beam consider Figure 1. A square beam is made of four identical plates connected at their edges. Under an axial compressive load each plate may buckle. Considering just one of the plates, the stress that will cause buckling depends on the ratio of plate width and thickness (b/t). Thinner wider plates with large b/t ratio will buckle at a lower stress than thicker narrower plates.

Figure 1: Plate Buckling Behavior.

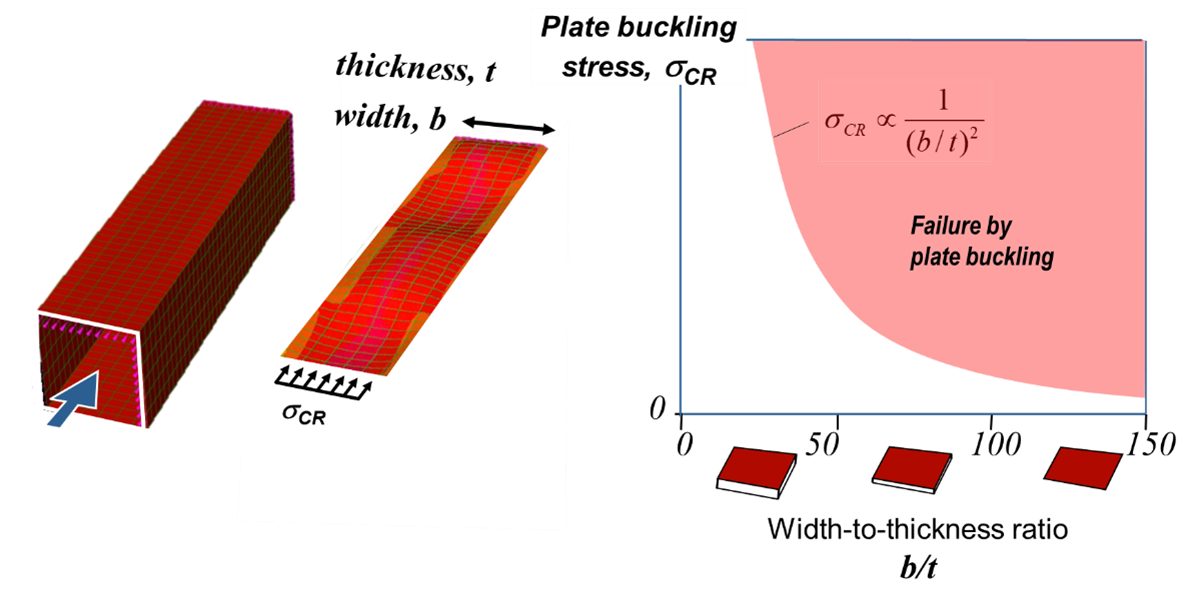

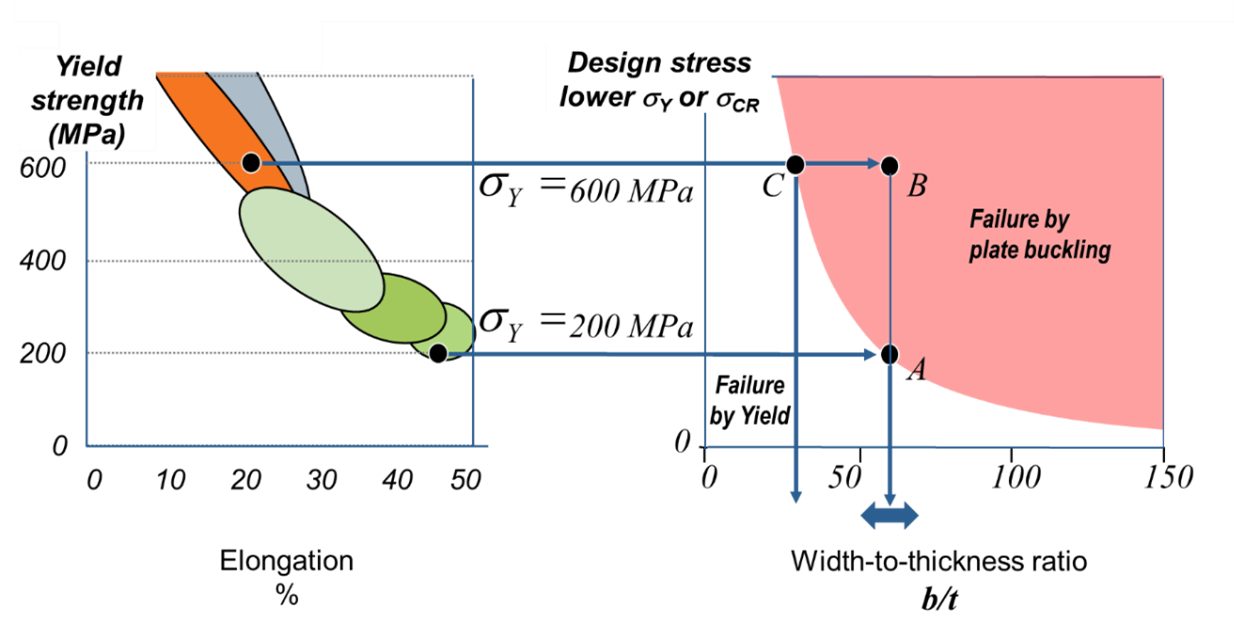

Now consider a plate of mild steel (200 MPa yield stress) which has been designed to buckle just as yield stress is reached, Point A in Figure 2. The plate would have a b/t ratio of approximately 60. This design is taking full advantage of the yield strength of the material.

Now consider the same plate but substituting an AHSS grade (600 MPa yield stress) as shown in Figure 2. The plate will buckle at the same 200 MPa before reaching the material’s potential, Point B in the figure. To take advantage of this materials yield strength, the proportions of the plate will need to be changed, Point C. This illustration demonstrates the need to consider plate buckling particularly in the application of AHSS grades.

Figure 2: AHSS Substitution in a Plate.

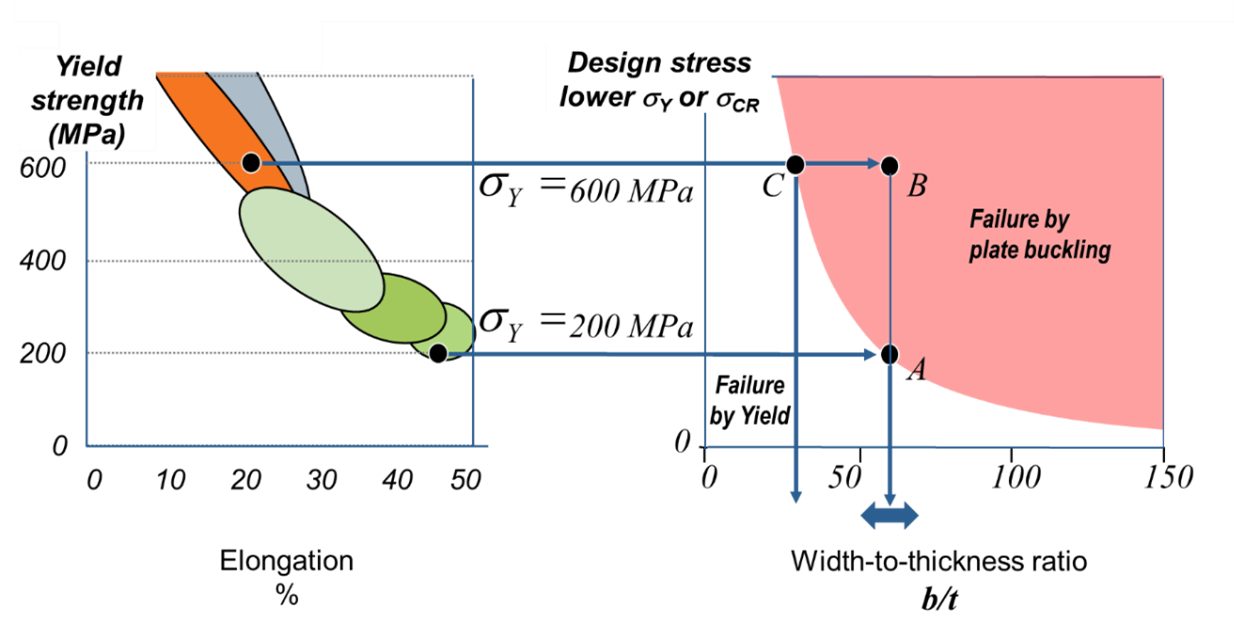

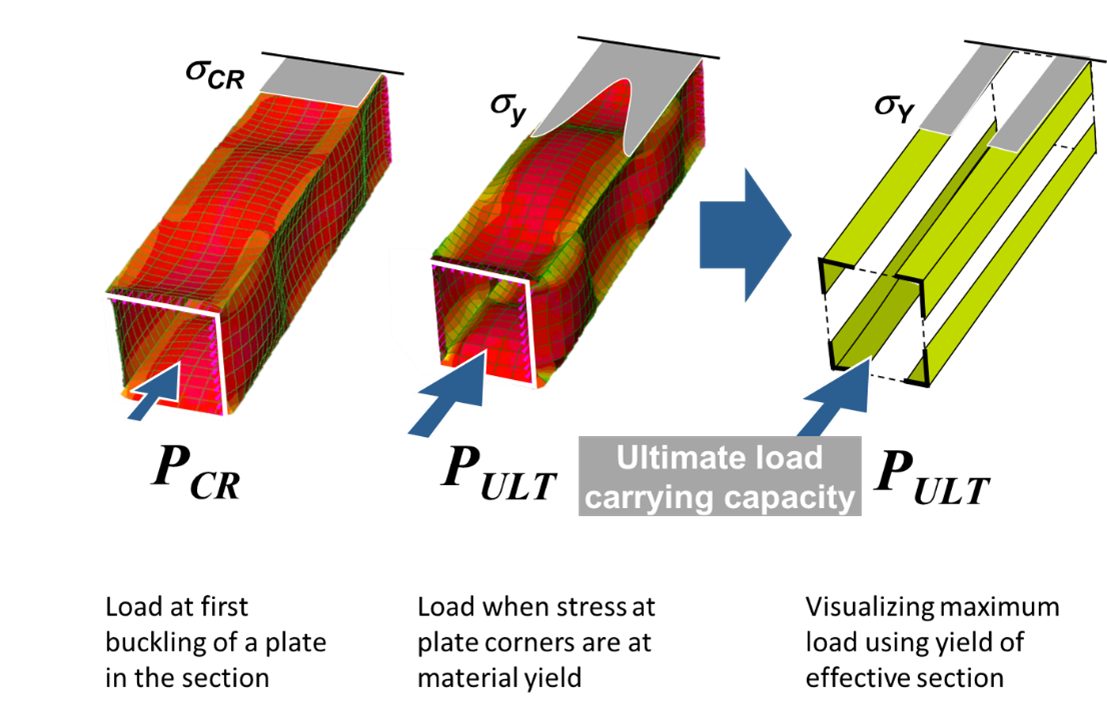

Moving from a single plate to the more complex case of a beam section of several plates, consider Figure 3. On the left is the beam made of four plates with a compressive load causing the plates to just begin to buckle. However, this condition does not represent the maximum load carrying ability of the beam. The load can be increased until the stress at the corners of the buckled plates are at the material yield stress, center in Figure 3. Note that in this condition the stress distribution across the plate is nonlinear with lower stress in the center of each plate. One means to model this complex state is by using an imaginary Effective Section. Here the center portion is visualized as being removed and the remainder of the section is stressed uniformly at yield. The amount of plate width to be removed is determined by theory.W-21, A-42, Y-9, M-18 The effective section is a convenient way to visualize the efficiency of a section design given the material grade and provides an estimate of the maximum load carrying ability of the beam.

Figure 3: Concept of Effective Section.

Geometric Analysis of Sections – GAS2.0

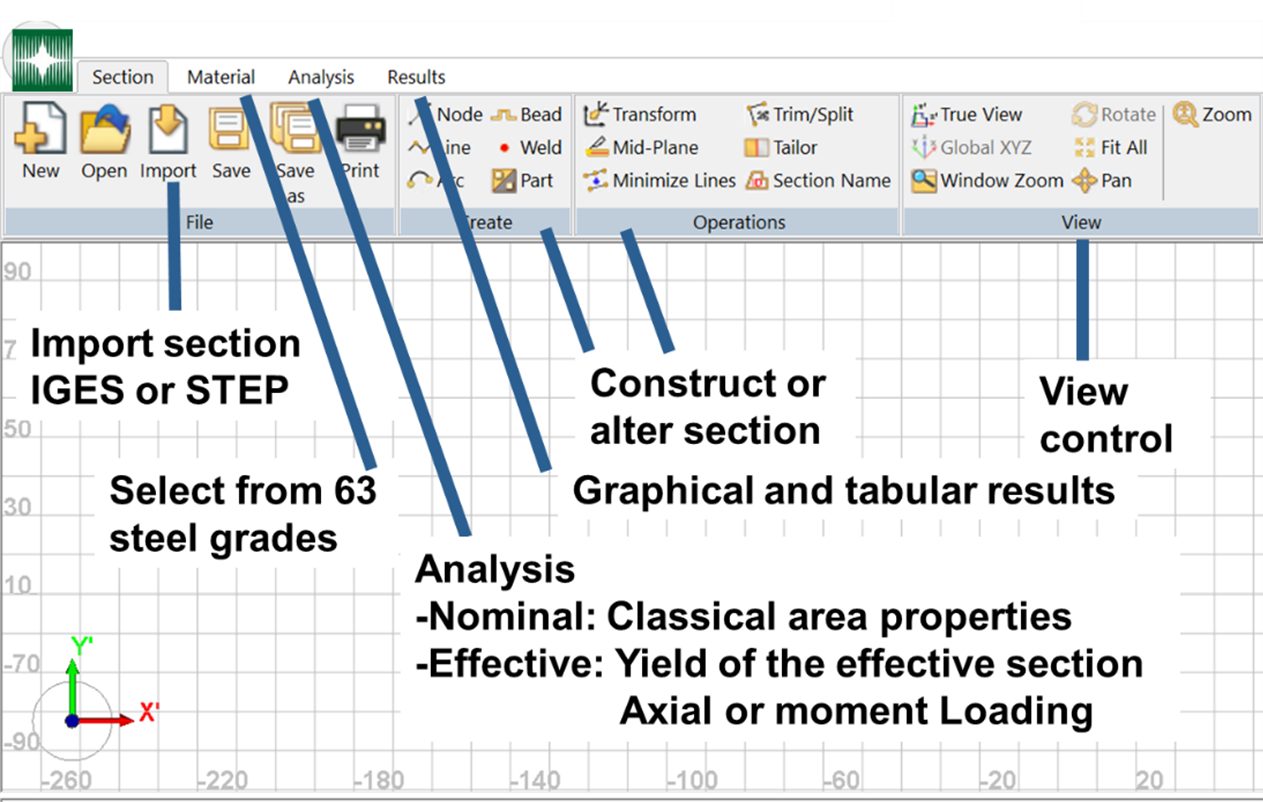

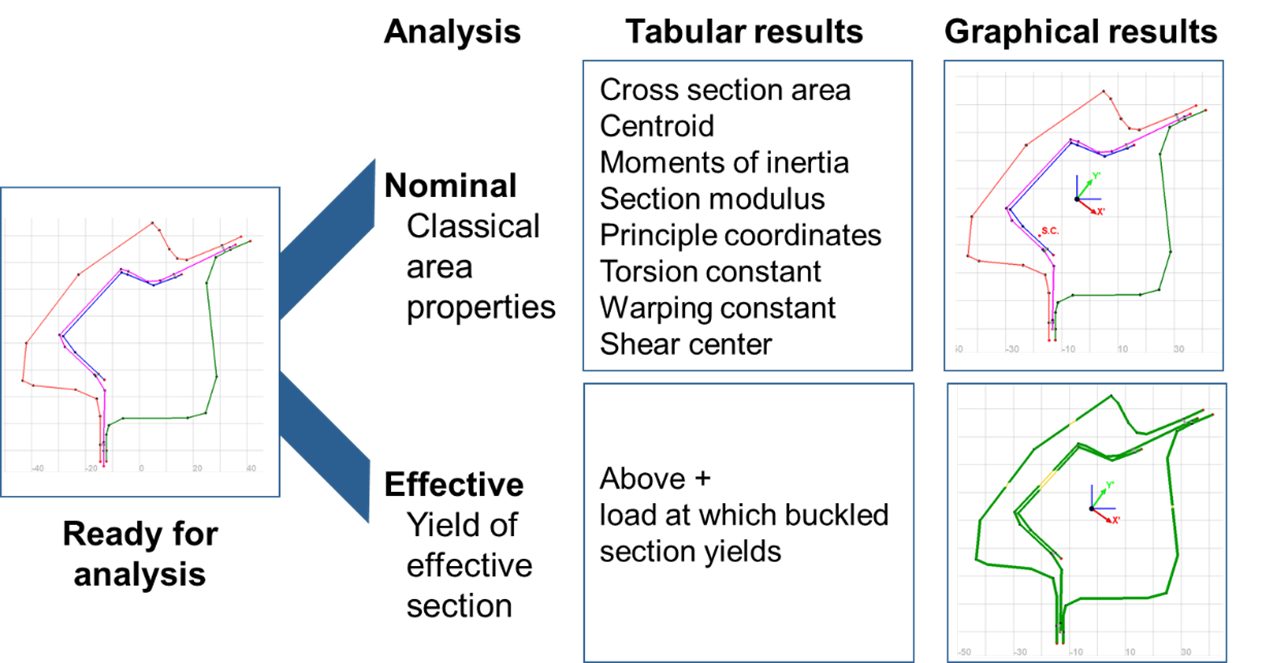

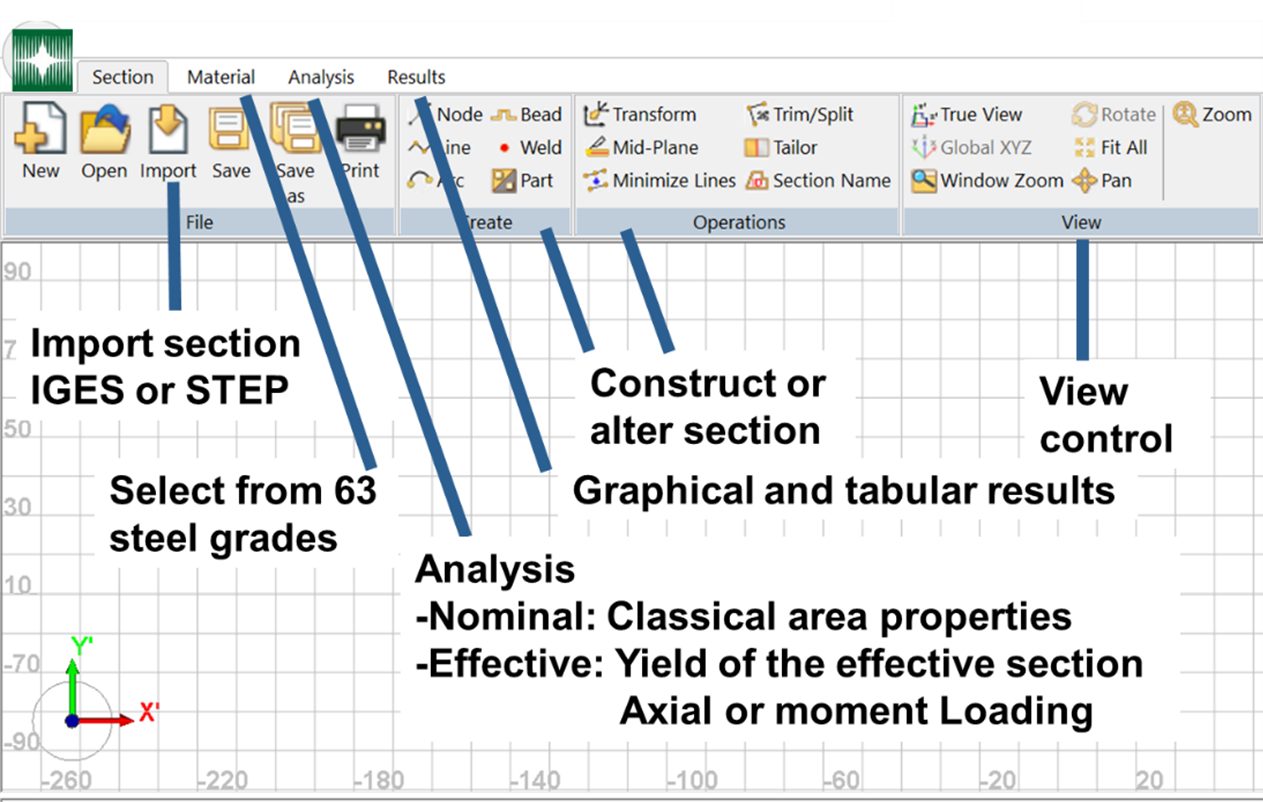

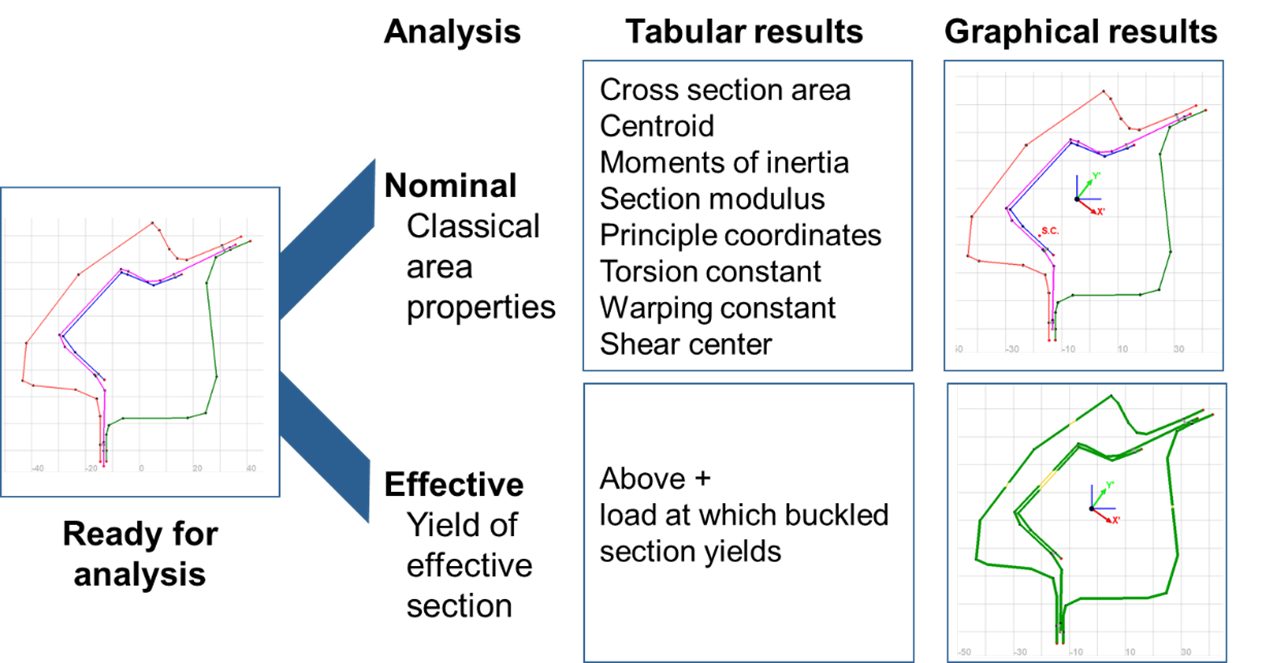

Geometrical Analysis of Sections software determines the effective section for complex automotive sections. Figure 4 illustrates the GAS2.0 user interface. The user has the ability to construct sections or to import section data from a CAD system. Material properties for 63 steel grades are preloaded with the ability to also add user-defined steel grades. Two types of analysis are available. Nominal analysis, which provides classical area properties of the section, and Effective analysis which determines the effective section at material yield. Figure 5 summarizes both the tabular results and graphical results for each type of analysis.

Figure 4: GAS2.0 User Interface.

Figure 5. GAS2.0 Analysis Results.

Figure 6 illustrates an example of an Effective Analysis for a rocker section. In the graphical screen, the effective section is shown in green. Ideally, the whole section would be effective to fully use the materials yield capability. Also shown in the graphical screen are the section centroid, orientation of the principle coordinates, and stress distribution. In the right text box are tabular results. At the bottom of the tabular results is the axial load that causes this stress state and represents the ultimate load carrying ability of this section.

Figure 6: GAS2.0 Graphical Results.

It is clear that much of the material in the section of Figure 6 is not fully effective. GAS2.0 allows the user to conveniently modify the section. For example, in Figure 7 a bead has been added to the left side wall increasing its bulking resistance. Note that the side wall is now largely effective, and the ultimate load at the bottom of the text box has increased substantially.

Figure 7: Improved Design Concept.

Role of GAS in the Design Process

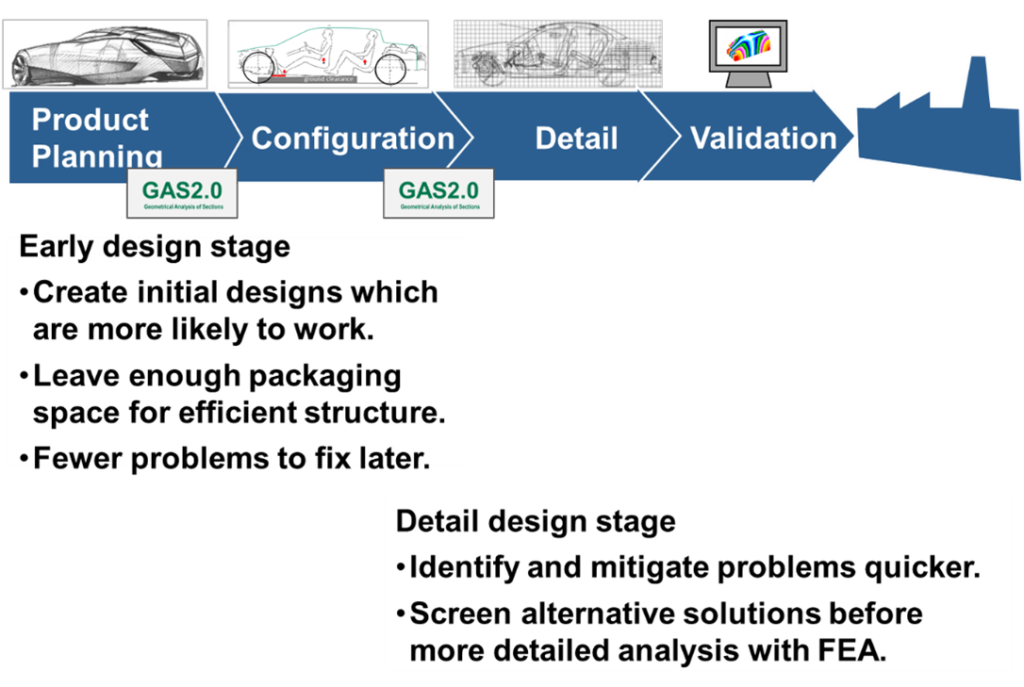

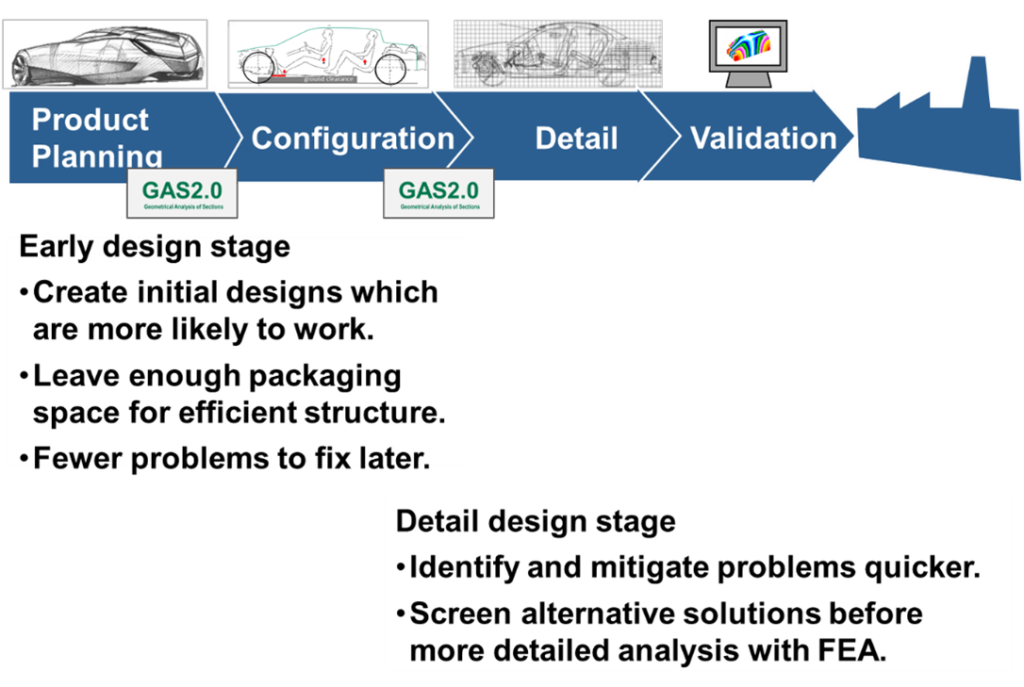

GAS2.0 can play a significant role in early stage design, see Figure 8, by quickly creating initial designs which are more likely to function and to ensure that adequate package space is set aside for structure. This will result in fewer problems to fix later in the design sequence. During the detail design stage, GAS2.0 can supplement Finite Element Analysis by identifying problems earlier, and by screening design concepts for those with the greatest promise prior to more detailed analysis by FEA.

Figure 8: Role of GAS2.0 in Design Process.

GAS2.0 is available for free download at www.steel.org, Included in the resources at steel.org is an American Iron and Steel Institute introductory webinar conducted by Dr. Don Malen on 16 June 2020, as well as a number of GAS2.0 tutorials and training modules.

homepage-featured-top, main-blog

In this edition of AHSS Insights, George Coates and Menachem Kimchi get back to basics with important fundamentals in forming and joining AHSS.

As the global steel industry continues its development of Advanced High-Strength Steels (AHSS), including 3rd Gen products with enhanced formability, we’re reminded that successful application is still dependent on the fundamentals, both in forming and joining. In this blog article, we address some of those forming considerations, as well as highlighting common joining issues in manufacturing.

Forming Considerations

The somewhat lower formability of AHSS compared to mild steels can almost always be compensated for by modifying the design of the component and optimizing blank shape and the forming process.

In stamping plants, we’ve observed inconsistent practices in die set-up and maintenance, surface treatments and lubrication application. Some of these inconsistencies can be addressed through education, via training programs on AHSS Application Guidelines. These Guidelines share best practices and lessons learned to inform new users on different behaviors of specific AHSS products, and the necessary modifications to assist their application success. In addition to new practices, we’ve learned that applying process control fundamentals become more critical as one transitions from mild steels to AHSS, because the forming windows are smaller and less forgiving, meaning these processes don’t tolerate variation well. If your present die shop is reflective of housekeeping issues, such as oil and die scrap on the floor or die beds, you are a candidate for a shop floor renovation or you will struggle forming AHSS products.

Each stamping operation combines three main elements to achieve a part meeting its desired functional requirements:

There is good news, in that our industry is responding with new products and services to improve manufacturing performance and save costs.

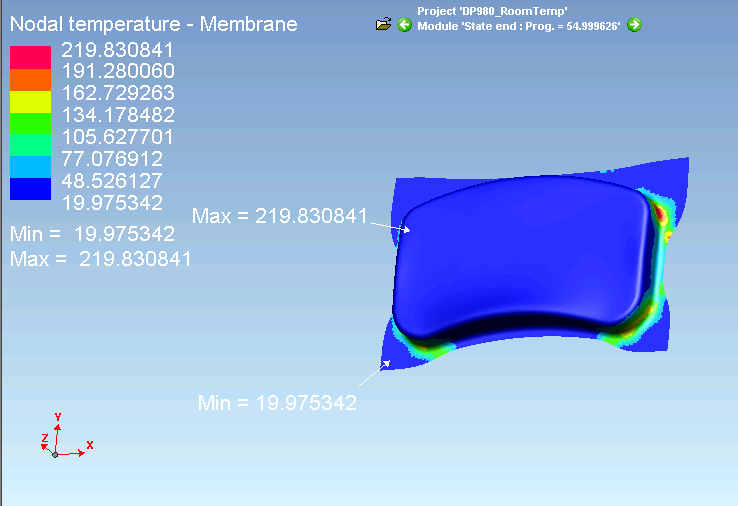

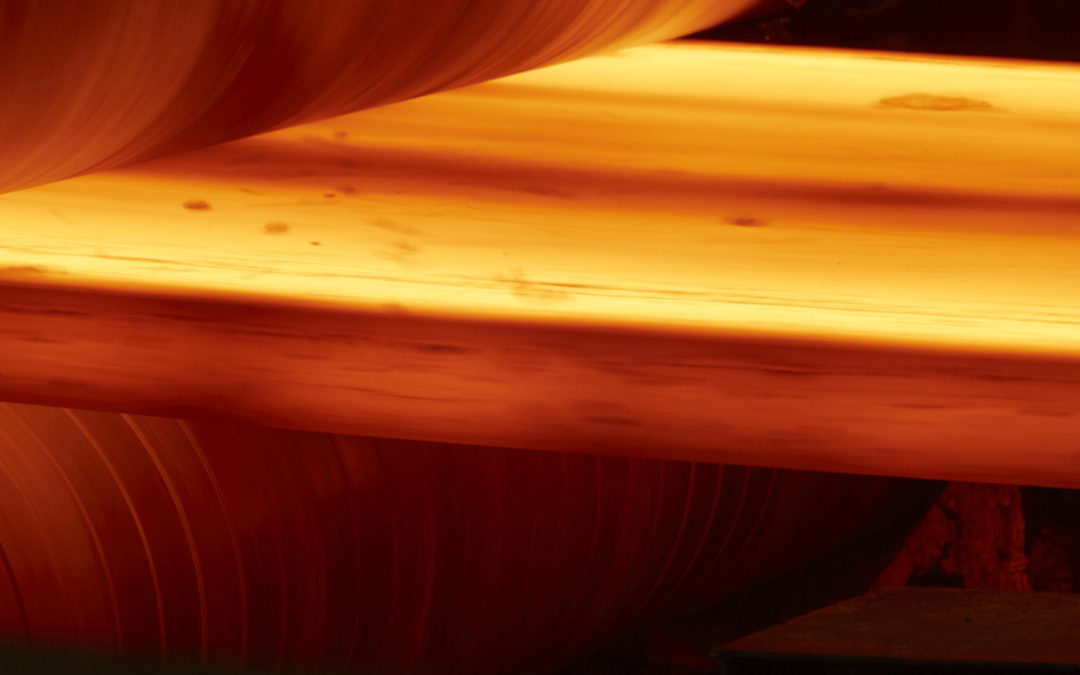

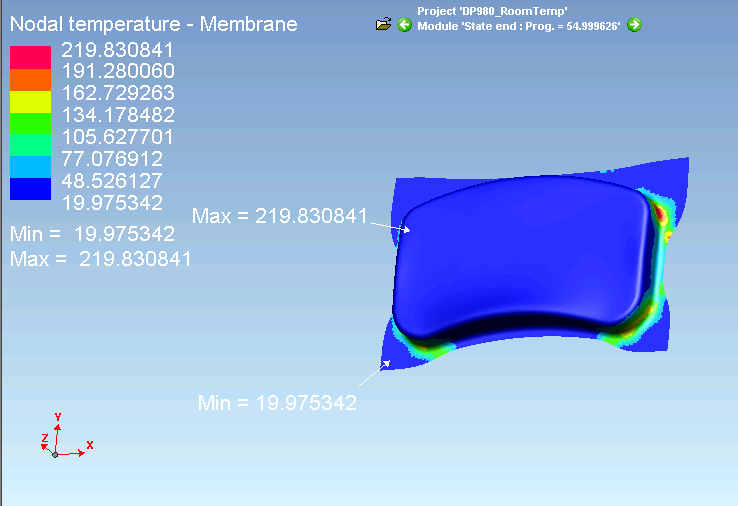

As an example, lubrication application is often overlooked, and old systems may be ineffective. In the forming of AHSS, part temperatures can become excessive, and break down lubricant performance. Figure 1 shows an example of part temperatures from an Ohio State University study conducted with DP 980 steels.O-1

Figure 1: Example Temperature distribution for DP 980 Steel.O-1

Stampers often respond by “flooding” the process with extra lubricant, thinking this will solve their problem. Instead, lubricant viscosity and high temperature stability are the most important considerations in the lubricant selection, and new types exist to meet these challenges. Also, today there are new lubrication controllers that can finely control and disperse wet lubricants evenly across the steel strip, or in very specific locations, if forming requirements are localized. These enable better performance while minimizing lubricant waste (saving cost), a win-win for the pressroom.

Similarly, AHSS places higher demands on tool steels used in forming and cutting operations. In forming applications, galling, adhesive wear and plastic deformation are the most common failure mechanisms. Surface treatments such as PVD, CVD and TD coatings applied to the forming tool are effective at preventing galling. Selection of the tool steel and coating process used for forming AHSS will largely depend on the:

- Strength and thickness of the AHSS product,

- Steel coating,

- Complexity of the forming process, and

- Number of parts to be produced.

New die materials such as “enhanced D2” are available from many suppliers. These improve the balance between toughness, hardness and wear resistance for longer life. These materials can be thru-hardened, and thus become an excellent base material for PVD or secondary surface treatments necessary in the AHSS processing. And new tool steels have been developed specifically for hot forming applications.

Joining Considerations

In high-volume production different Resistance Spot Welding (RSW) process parameters can be used depending on the application and the specifications applied. Assuming you chose the appropriate welding parameters that allows for a large process window, manufacturing variables may ruin your operation as they strongly effect the RSW weld quality and performance.

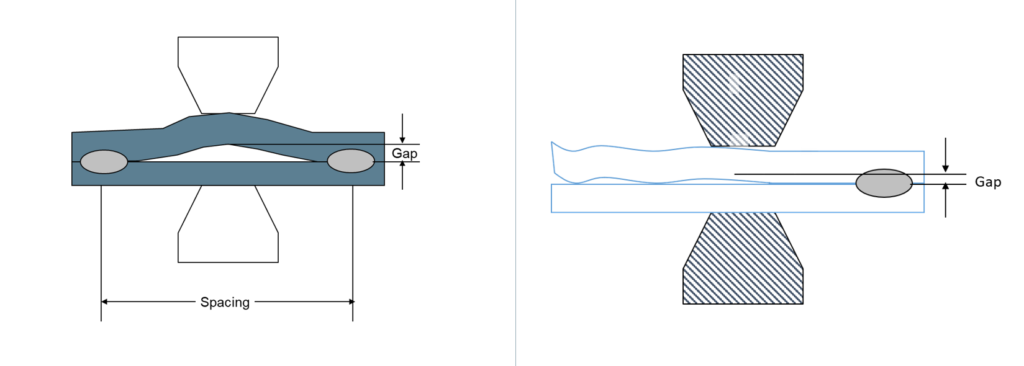

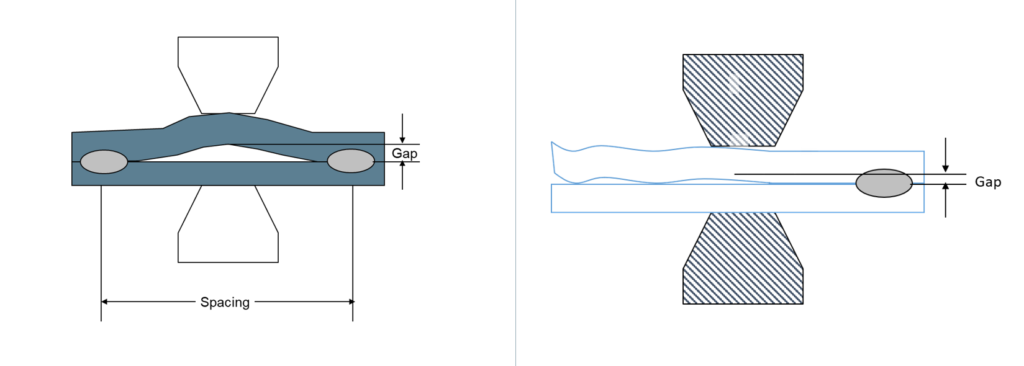

Material fit-up

One of the great advantages of the RSW process is the action of clamping the material together via the electrode force applied during the process. However due to the pre-welding condition/processing such as the stamping operation, this fit-up issue, as shown in Figure 2, can be very significant especially in welding an AHSS product. In this case the effective required force specified during the process setup for the application is significantly reduced and can result in an unacceptable weld, over-heating, and severe metal expulsion. If the steels are coated, higher probability for Liquid Metal Embrittlement (LME) cracking is possible.

Figure 2: Examples of Pre-Welding Condition/Processing Fit-Up Issues.

For welding AHSS, higher forces are generally required as a large part of the force is being used to force the parts together in addition to the force required for welding. Also, welding parameters may be set for pre-heating with lower current pulses or current up-slope to soften the material for easier material forming and to close the gap.

Electrodes Misalignment

During machine set up, the RSW electrodes need to be carefully aligned as shown in Figure 3A. However, in many production applications, electrode misalignment is a common problem.

Electrode misalignment in the configurations shown in Figure 3B may be detrimental to weld quality of any RSW application. Of course, the electrode misalignment shown in this figure is exaggerated but the point is that it happens frequently on manufacturing welding lines.

In these cases, the intendent contact between the electrodes is not achieved and thus the current density and the force density (pressure) required for producing an acceptable weld cannot be achieved. With such conditions, overheating, expulsion, sub-size welds and extensive electrode wear will result. Again, if coated steels are involved, the probability for LME cracking is higher.

Note also that following specifications or recommendations for water cooling the electrode is always important for process stability and extending electrode life.

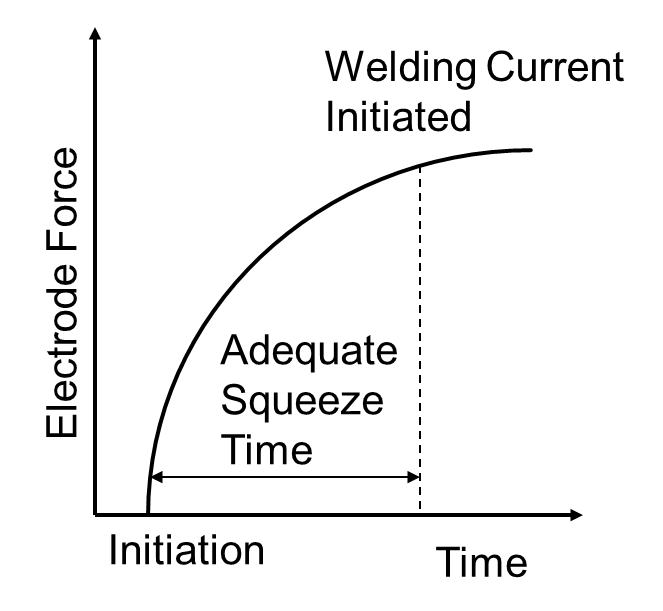

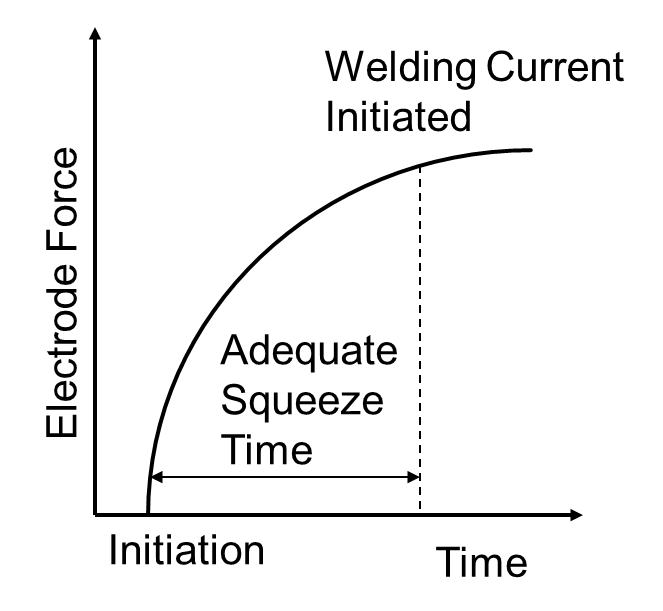

Figure 4: Sequence of Squeeze Time and Welding Current Initiation.

Squeeze Time

The squeeze time is the time required for the force to reach the level needed for the specific application. Welding current should be applied only after reaching this force, as indicated in Figure 4. All RSW controllers enable the easy control of squeeze time, just as with the weld time, for example. In many production operations, a squeeze time is used that is too low due to lack of understanding of its function. If squeeze time is too low, high variability in weld quality in addition to severe expulsion will be the result.

The squeeze time required for an application depends on the machine type and characteristics (not an actual welding parameter such as weld time or welding current for example).

Some of the more modern force gauges have the capability to produce the curve shown in the Figure so adequate squeeze time will be used. If you do not know what the required squeeze time for your machine/application is, it is recommended to use a longer time.

For more on these topics, browse the Forming and Joining menus of these Guidelines.