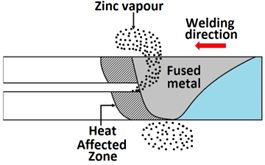

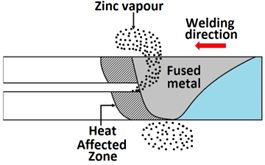

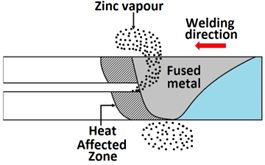

This article focuses on the role of Zinc coatings in causing so-called blowhole defects during gas metal arc welding of automotive body-in-white panels. Blowholes occur when vaporized coating material becomes trapped in the molten weld pool during solidification. This is more prevalent in overlap or T-joint configurations compared to butt joints, where vapors can escape more easily. Random variations can lead to differing pore rates in welded joints, necessitating a statistical approach to evaluation.

Experimental Plan and Methodology

An experimental plan, evaluating the factors contributing to blowhole formation, including heat input, filler wire type, gap distance, and welding conditions was used. Over 1,000 welds were performed to gather sufficient data for statistical analysis. The methodology focused on measuring pore rates and the length of defects through x-ray testing.

Figure 1: Blowholes are formed by vaporized Zinc escaping through the molten zone.

Solutions

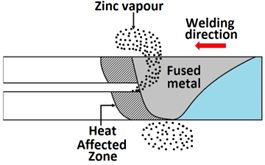

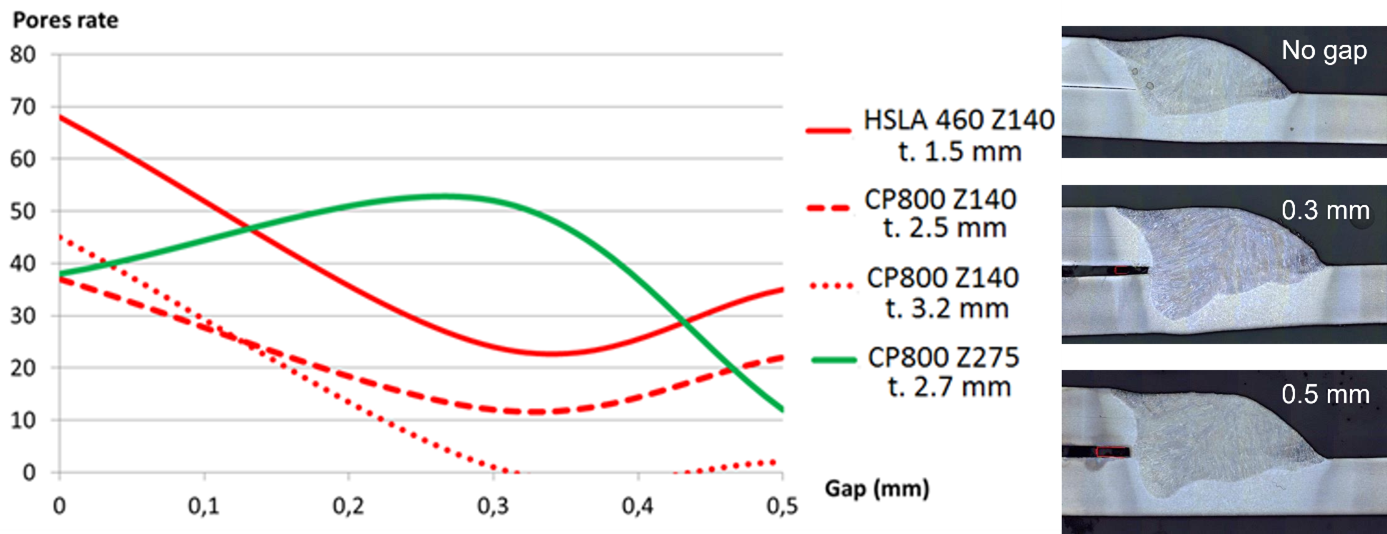

- Introduction of Gaps: A gap greater than 0.3 mm between sheets facilitates vapor extraction during welding, significantly reducing blowhole formation. Controlling the gap between sheets is challenging and costly in automotive assemblies. It may be an adequate solution, when the overlap width cannot be adjusted.

Figure 2: Pore rate in percent for different gap widths and steels (left) and cross-sections with increasing gaps (right). For normal coating level Z140, increasing the gap decreased pore and blowhole formation. Using a steel with significantly increased coating did not show this effect.

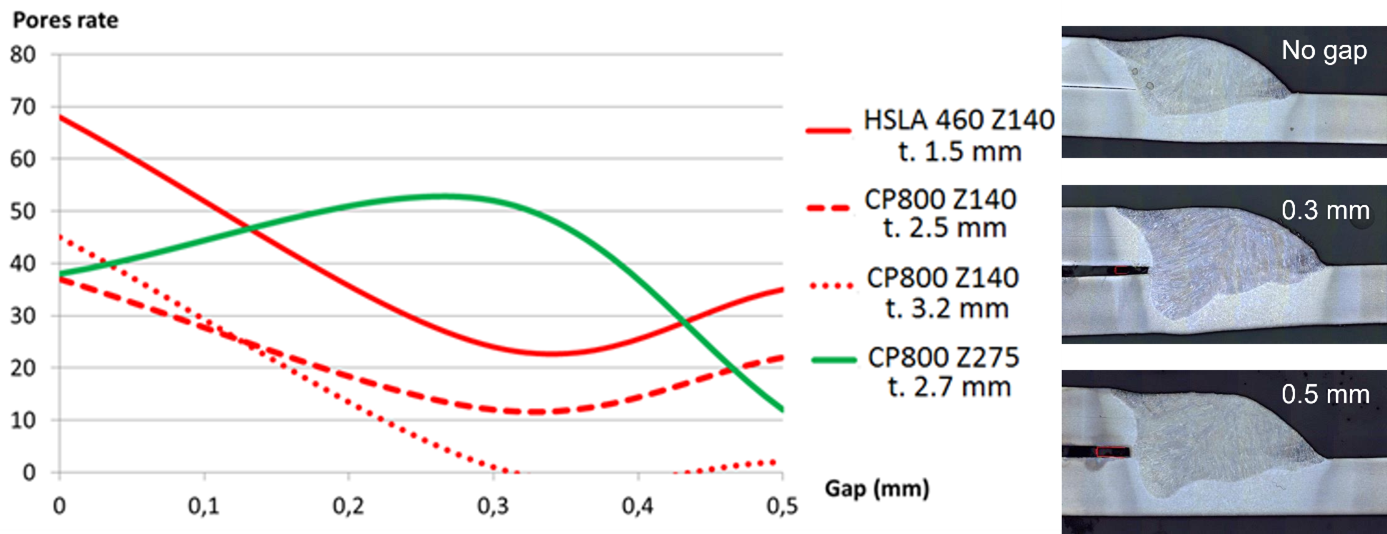

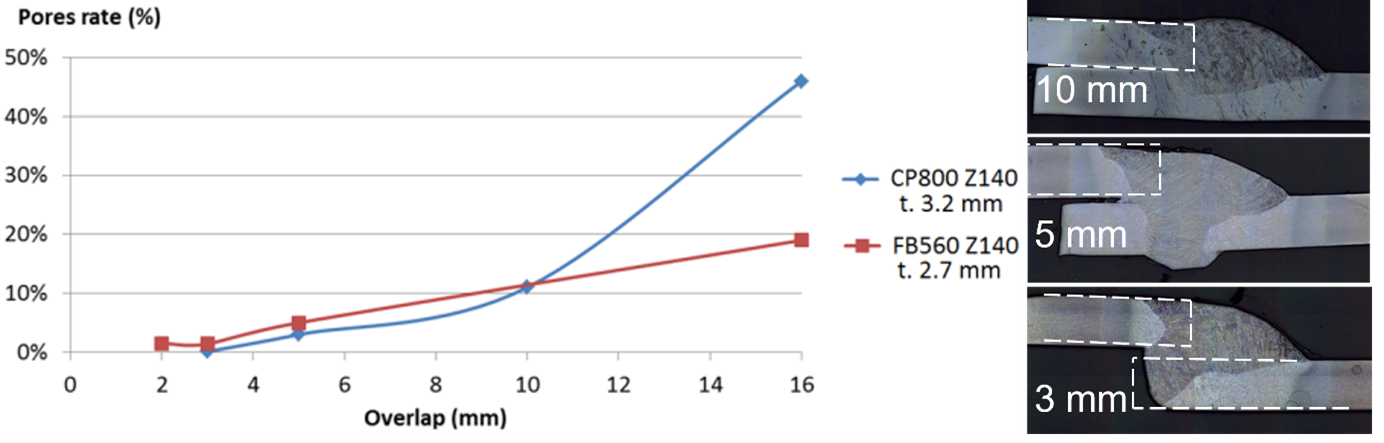

- Reduction of Overlap Width: Decreasing the overlap width not only helps vapors escape more easily but also reduces the overall weight of the assembly, making it the preferable solution

Figure 3: Pore rate in percent for increasing overlaps (left) and cross-sections with increasing overlap (right). Decreasing the overlap decreased pore and blowhole formation.

Effects on Mechanical Properties

Neither the gap nor overlap width significantly affected ultimate tensile strength (UTS) or fatigue performance, if the gap remained below 1 mm. The presence of blowholes did not adversely affect fatigue performance, although they could lead to reduced static strength of the joint if located at critical points within the load path.

Key Messages

- MAG welding of zinc-coated steels can lead to blowholes.

- Utilizing pulsed current may help minimize these defects, but welding parameters have limited effects on blowhole occurrence.

- Introducing a gap or reducing overlap width are effective strategies to mitigate these issues, with no impact on mechanical properties.

Source

J. Haouas, Solutions for improvement of zinc coated steels arc welding, ICWAM conference 2017, Metz

Joining, Laser Welding, Press Hardened Steels

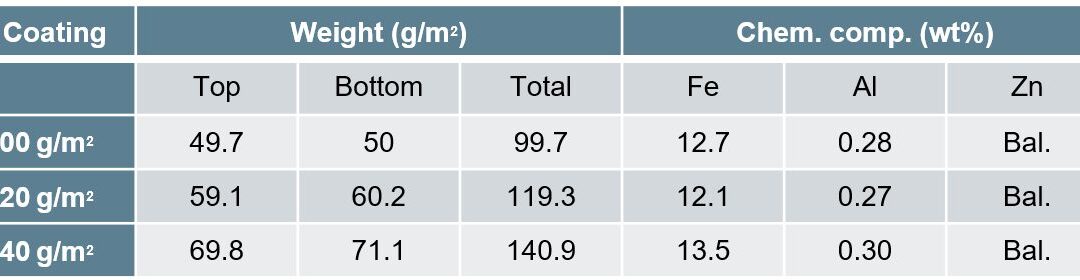

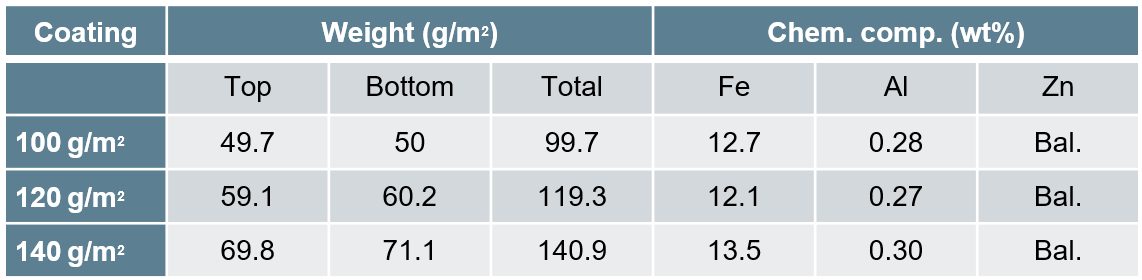

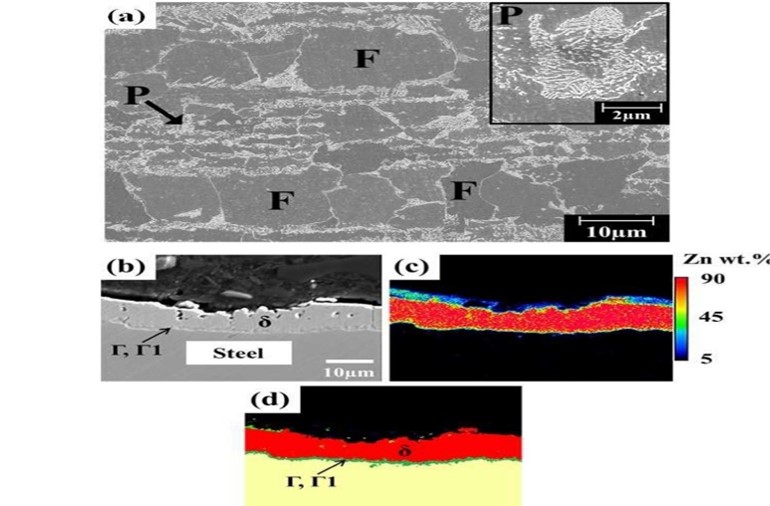

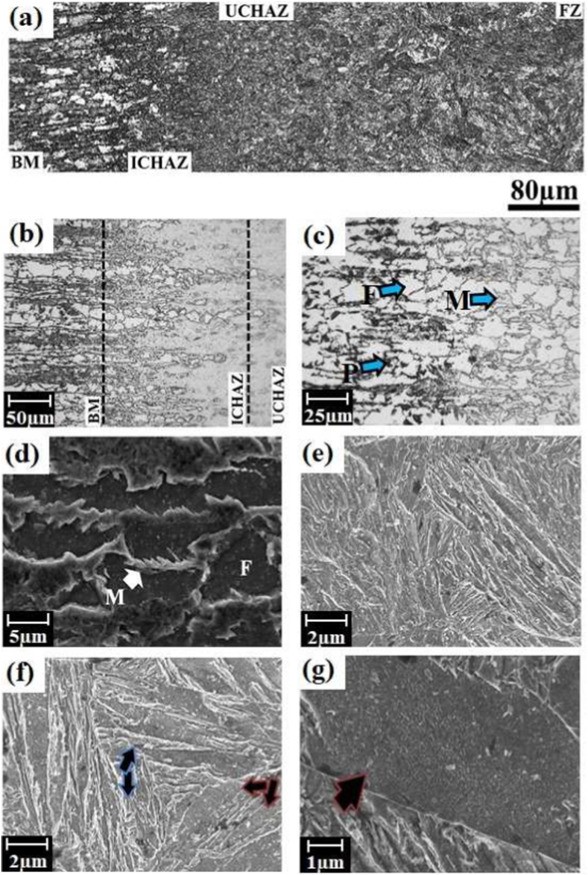

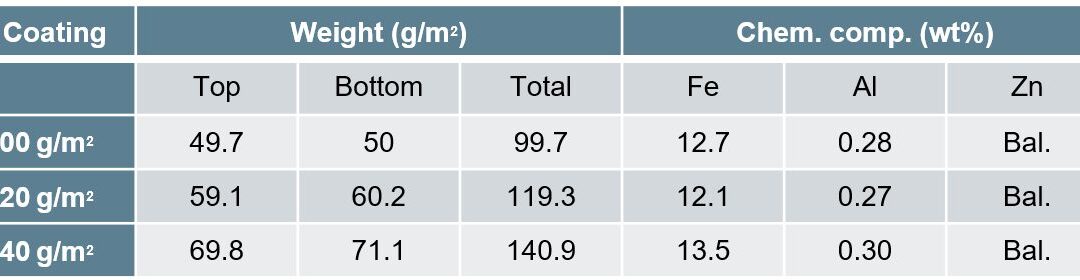

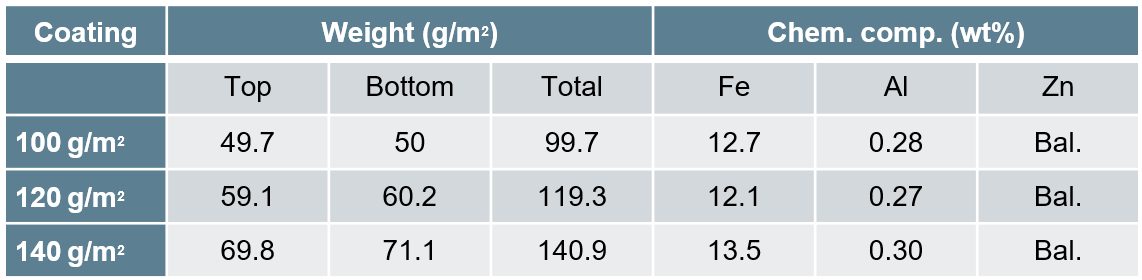

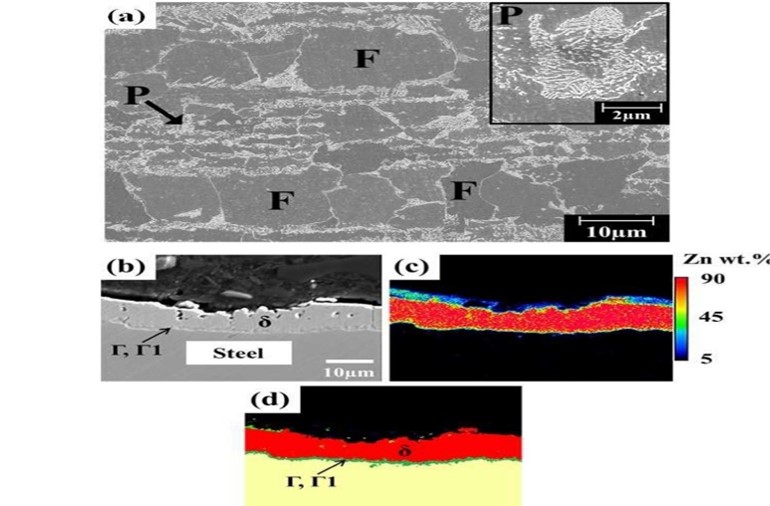

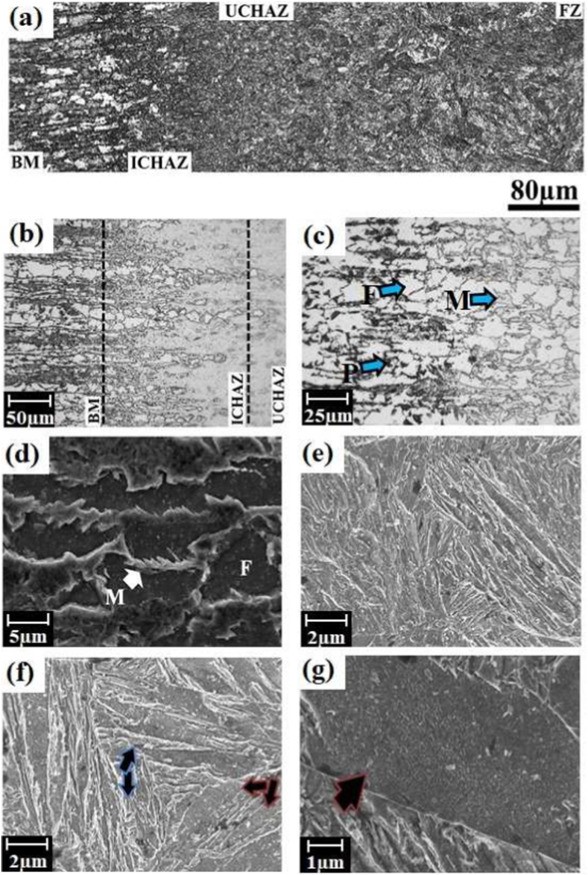

This studyR-25, conducted by the Centre for Advanced Materials Joining, Department of Mechanical & Mechatronics Engineering, University of Waterloo, and ArcelorMittal Global Research, utilized 2mm thick 22MnB5 steel with three different coating thicknesses, given in Table 1. The fiber laser welder used 0.3mm core diameter, 0.6mm spot size, and 200mm beam focal length. The trials were done with a 25° head angle with no shielding gas but high pressure air was applied to protect optics. Welding passes were performed using 3-6kW power increasing by 1 kW and 8-22m/min welding speed increasing by 4m/min. Compared to the base metal composition of mostly ferrite with colonies of pearlite, laser welding created complete martensitic composition in the FZ and fully austenized HAZ while the ICHAZ contained martensite in the intergranular regions where austenization occurred.

Table 1: Galvanneal Coatings.R-25

Figure 1: Base metal microstructure(P=pearlite, F=ferrite, Γ=Fe3Zn10, Γ1=Fe5Zn21 and δ=FeZn10).R-25

Figure 2: Welded microstructure — (a) overall view, (b) HAZ, (c) ICHAZ at low and (d) high magnifications, (e) UCHAZ (f) FZ, and (g) coarse-lath martensitic structure (where M; martensite, P: pearlite, F: ferrite).R-25

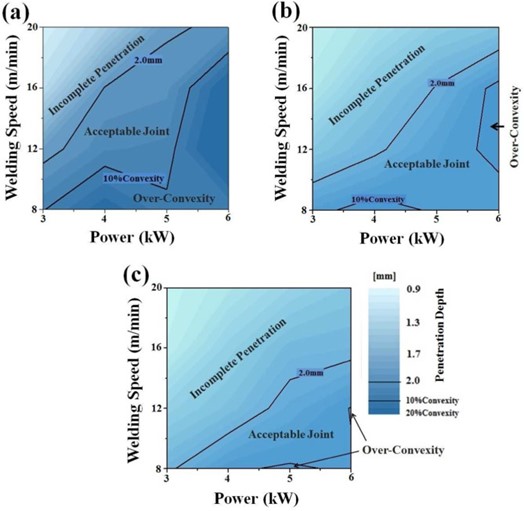

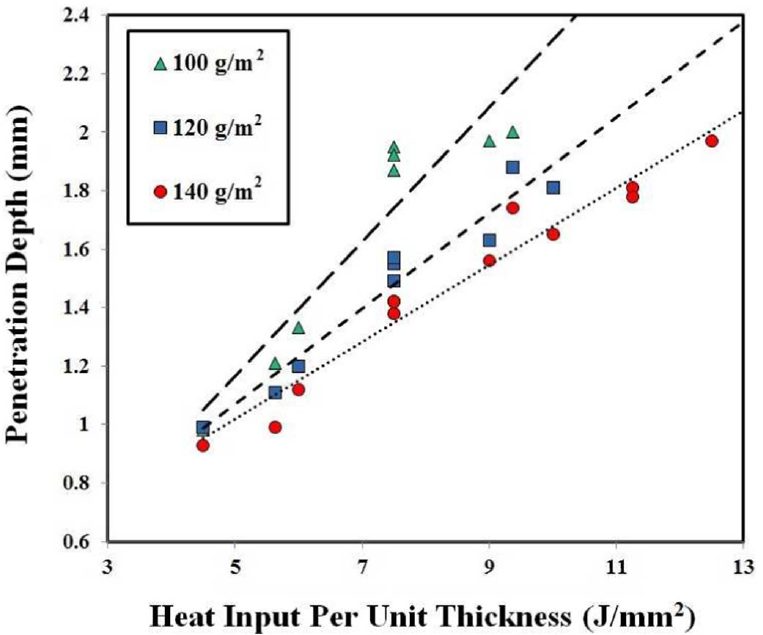

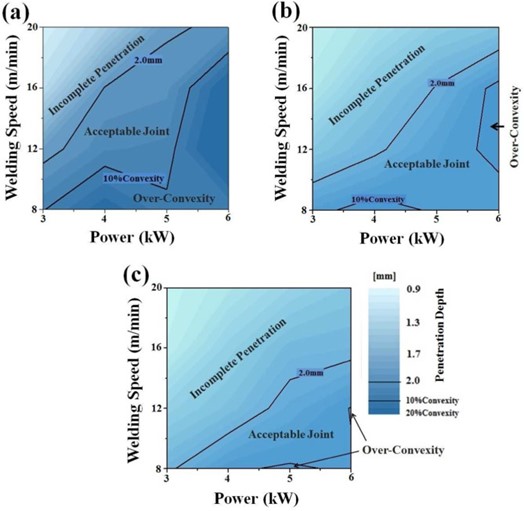

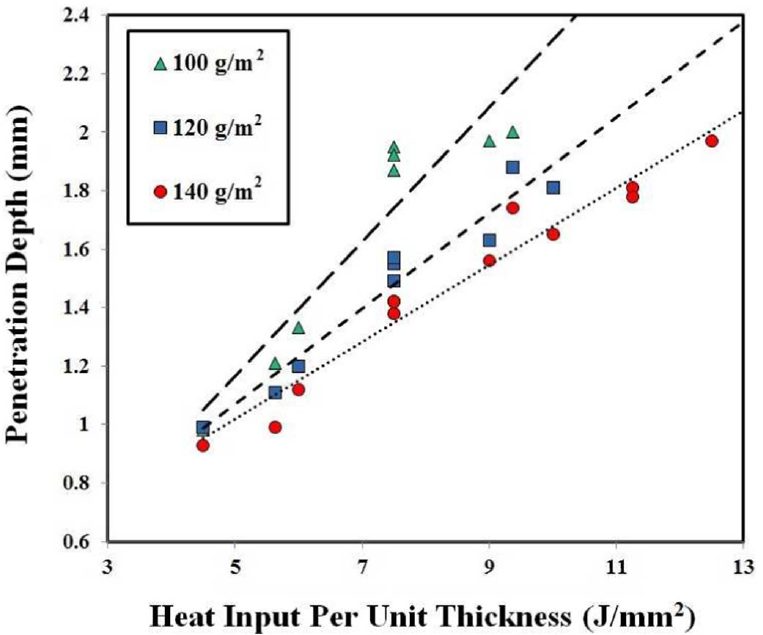

Given the lower boiling temperature of Zn at 900 °C as compared to Fe, the interaction of the laser with the Zn plasma that forms upon welding affects energy deliverance and depth of penetration. Lower coating weight of (100 g/m2) resulted in a larger process window as compared to (140 g/m2). Increased coating weight will reduce process window and need higher power and lower speeds in order to achieved proper penetration as shown in Figure 3 and Figure 4. Depth of penetration due to varying welding parameters was developed:

d=(H-8.6+0.08C)/(0.09C-4.8)

[d= depth of penetration(mm), H= heat input per unit thickness(J/mm2), C= coating weight(g/m2)]

Given the reduction in power deliverance, with an increase in coating weight there will be an expected drop in FZ and HAZ width. Regardless of the coating thickness, the HAZ maintained its hardness between BM and FZ. No direct correlation between coating thickness and YS, UTS, and elongation to fracture levels were observed. This is mainly due to the failure location being in the BM.

Figure 3: Process map of the welding window at coating weight of (a) 100 g/m2, (b) 120 g/m2, and (c) 140 g/m2.R-25

Figure 4: Heat input per unit thickness vs depth of penetration.R-25

Blog, RSW Joint Performance Testing

top-of-page

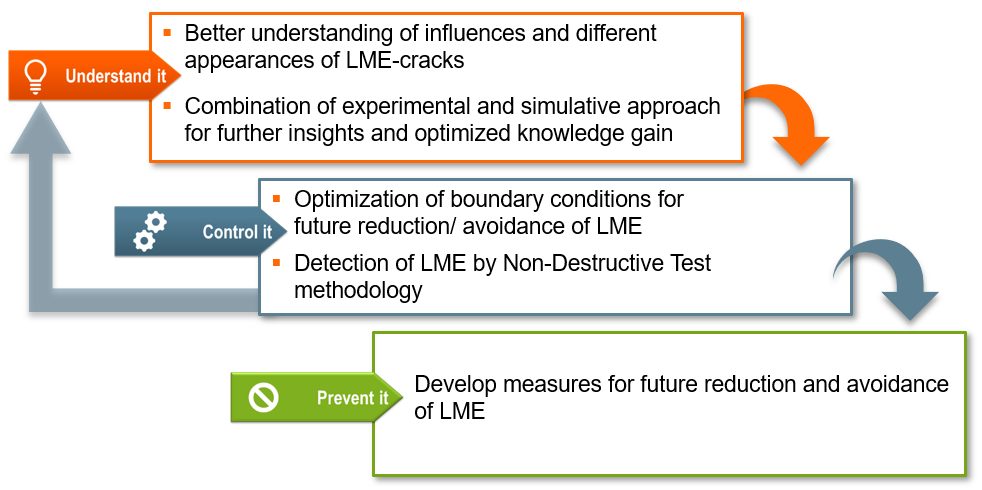

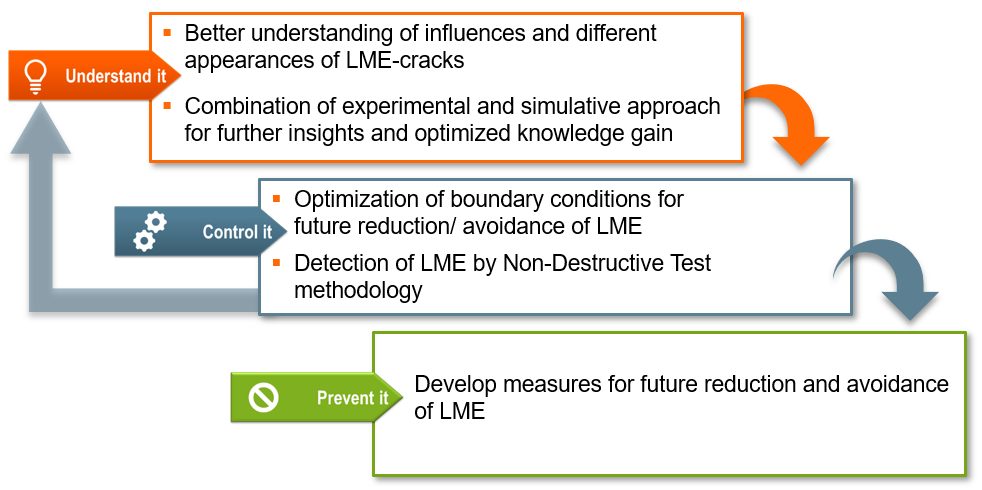

Results of a Three-Year LME Study

WorldAutoSteel releases today the results of a three-year study on Liquid Metal Embrittlement (LME), a type of cracking that is reported to occur in the welding of Advanced High-Strength Steels (AHSS).The study results add important knowledge and data to understanding the mechanisms behind LME and thereby finding methods to control and establish parameters for preventing its occurrence. As well, the study investigated possible consequences of residual LME on part performance, as well as non-destructive methods for detecting and characterizing LME cracking, both in the laboratory and on the manufacturing line (Figure 1).

Figure 1: LME Study Scope

The study encompassed three different research fields, with an expert institute engaged for each:

- Laboratory of Materials and Joining Technology (LWF) Paderborn University, Paderborn, Germany, for experimental research,

- The Institute de Soudure, Yutz, France, for investigations regarding non-destructive testing, and

- Fraunhofer Institute for Production Systems and Design Technology (IPK), Berlin, Germany, for the development of a simulation model to accurately replicate welding conditions resulting in LME.

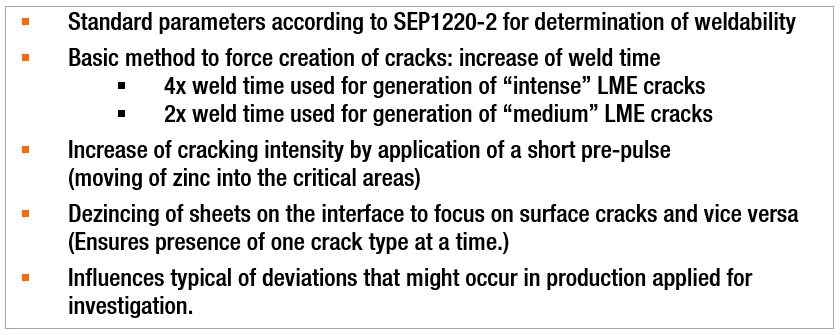

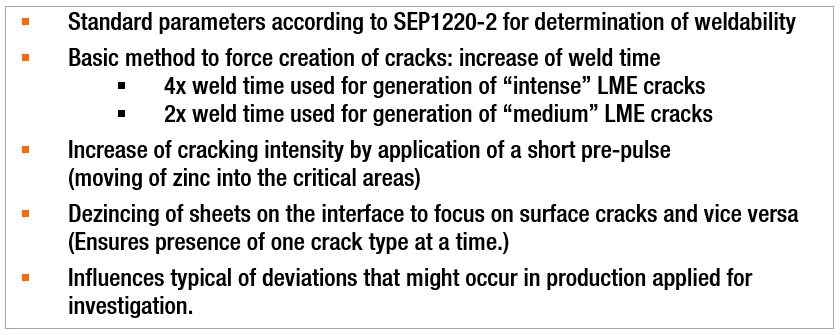

A portfolio containing 13 anonymized AHSS grades, including dual phase (DP), martensitic (MS) and retained austenite (RA) with an ultimate tensile strength (UTS) of 800 MPa and higher, was used to set up a testing matrix, which enabled the replication of the most relevant and critical material thickness combinations (MTC). All considered MTCs show a sufficient weldability under use of standard parameters according to SEP1220-2. Additional MTCs included the joining of various strengths and thicknesses of mild steels to select AHSS in the portfolio. Figure 2 provides the welding parameters used throughout the study.

Figure 2: Study Welding Parameters

In parallel, a 3D electro-thermomechanical simulation model was set up to study LME. The model is based on temperature-dependent material data for dual phase AHSS as well as electrical and thermal contact resistance measurements and calculates local heating due to current flow as well as mechanical stresses and strains. It proved particularly useful in providing additional means to mathematically study the dynamics observed in the experimental tests. This model development was documented in two previous AHSS Insights blogs (see AHSS Insights Related Articles below).

Understanding LME

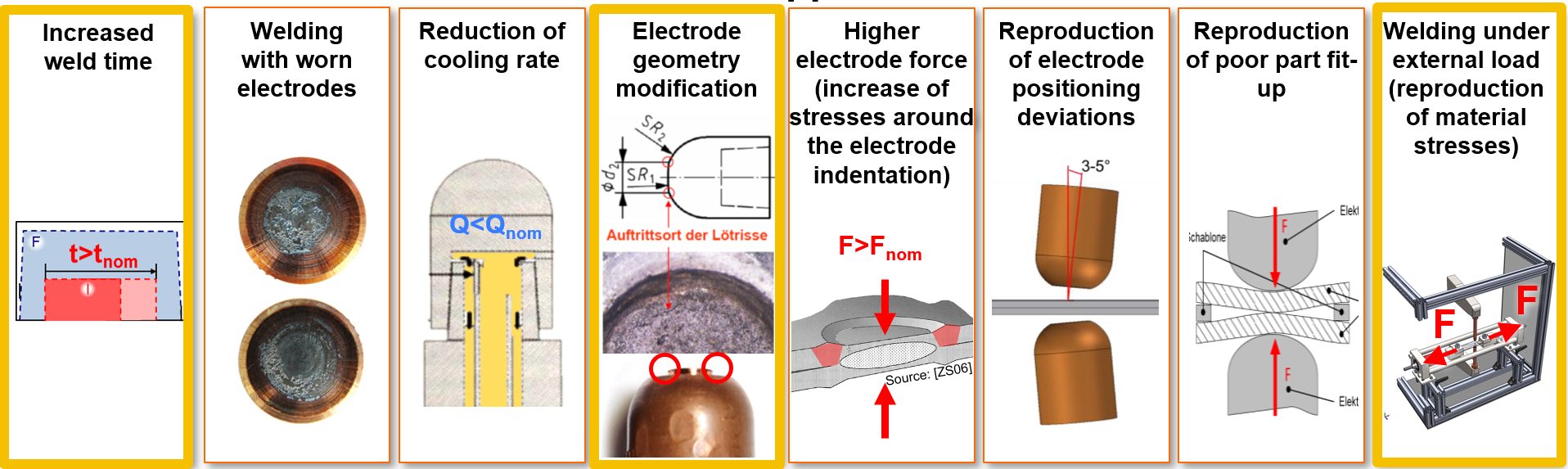

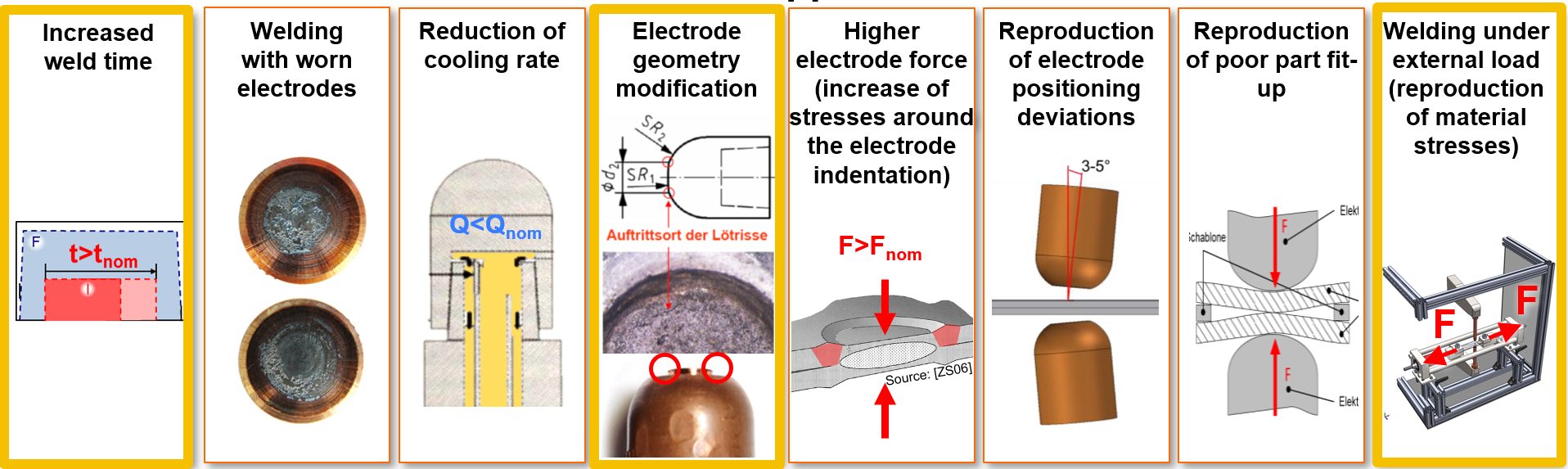

The study began by analyzing different influence factors (Figure 3) which resembled typical process deviations that might occur during car body production. The impact of the influences was analyzed by the degree of cracking observed for each factor. A select number of welding set-ups from these investigations were rebuilt digitally in the simulation model to replicate the process and study its dynamics mathematically. This further enabled the clarification of important cause-effect relationships.

Figure 3: Overview of All Applied Influence Factors (those outlined in yellow resulted in most frequent cracking.)

Generally, the most frequent cracking was observed for sharp electrode geometries, increased weld times and application of external loads during welding. All three factors were closely analyzed by combining the experimental approach with the numerical approach using the simulation model.

Destructive Testing – LME Effects on Mechanical Joint Strength

A destructive testing program also was conducted for an evaluation of LME impact on mechanical joint strength and load bearing capacity in multiple conditions, including quasi-static loading, cyclic loading, crash tests and corrosion. In summary of all load cases, it can be concluded that LME cracks, which might be caused by typical process deviations (e.g. bad part fit up, worn electrodes) have a low intensity impact and do not affect the mechanical strength of the spot weld. And as previously mentioned, the study analyses showed that a complete avoidance of LME during resistance spot welding is possible by the application of measures for reducing the critical conditions from local strains and exposure to liquid zinc.

Controlling LME

In welding under external load experiments, the locations of the experimental crack occurrence showed close correlation with the strains and remaining plastic deformations computed by the simulation model. It was observed that the cracks form at the location of the highest plastic strains, and material-specific threshold values for critical strains were derived. The threshold values then were used to judge the crack formation at elongated weld times.

At the same time, the simulation model pointed out a significant difference in liquid zinc diffusion during elongated weld times. Therefore, it is concluded that liquid zinc exposure time is a second highly relevant factor for LME formation.

The results for the remaining influence factors depended on the investigated MTCs and were generally less significant. In more susceptible MTCs (AHSS welded with thick Mild steel), no significant cracking occurred when welded using standard process parameters. Light cracking was observed for most of the investigated influences, such as low electrode cooling rate, worn electrode caps, electrode positioning deviations or for gap afflicted spot welds. More intense cracking (higher penetration depth cracking) was only observed when welding under extremely high external loads (0.8 Re) or, even more, as a consequence of highly increased weld times.

For the non-susceptible MTCs, even extreme situations and weld set-ups (such as the described elongated weld times) did not result in significant LME cracks within the investigated AHSS grades.

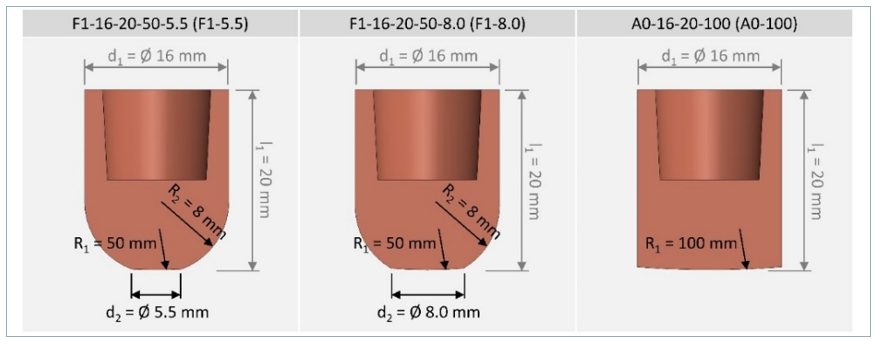

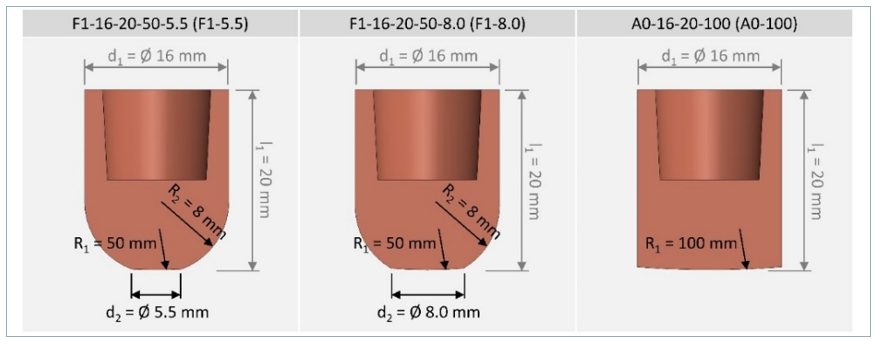

Methods for avoidance of LME also were investigated. Changing the electrode tip geometry to larger working plane diameters and elongating the hold time proved to eliminate LME cracks. In the experiments, a change of electrode tip geometry from a 5.5 mm to an 8.0 mm (Figure 4) enabled LME-free welds even when doubling the weld times above 600 ms. Using a flat-headed cap (with small edge radii or beveled), even the most extreme welding schedules (weld times greater than 1000 ms) did not produce cracks. The in-depth analysis revealed that larger electrode tip geometries clearly reduce the local plastic deformation around the indentation. This plastic strain reduction is particularly important, as longer weld times contribute to a higher liquid zinc exposure interval, leading to a higher potential for LME cracks.

Figure 4: Electrode Geometries Used in Study Experiments

It was also seen that as more energy flows into a spot weld, it becomes more critical to parameterize an appropriate hold time. Depending on the scenario, the selection of the correct hold time alone can make the difference between cracked and crack-free welds. Insufficient hold times allow liquid zinc to remain on the steel surface and increased thermal stresses that form after the lift-off of the electrode caps. Elongated hold times reduce surface temperatures, minimizing surface stresses and thus LME potential.

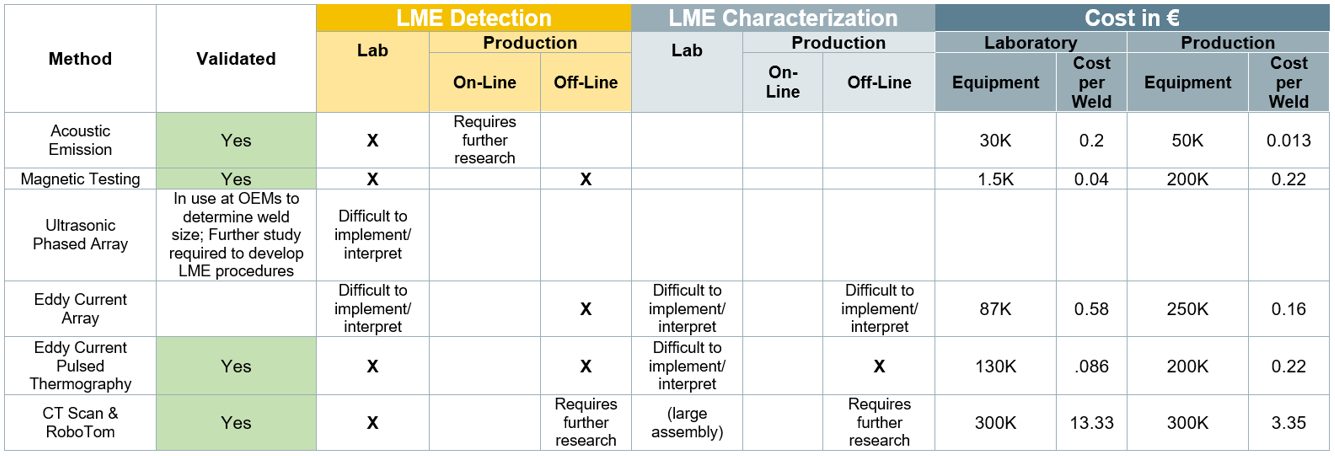

Non-Destructive Testing: Laboratory and Production Capabilities

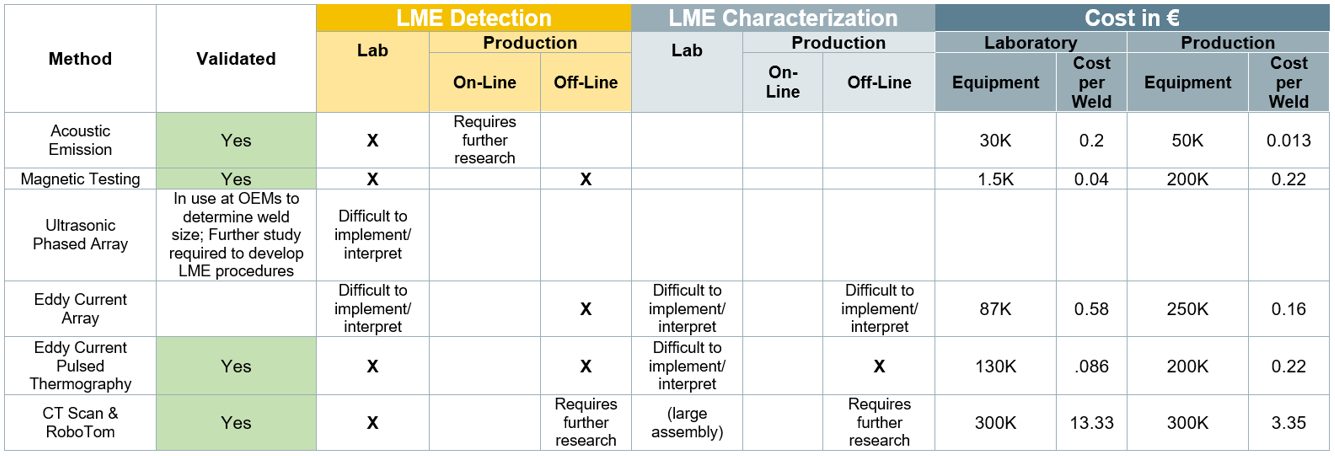

A third element of the study, and an aid in the control of LME, is the detection and characterization of LME cracks in resistance spot welds, either in laboratory or in production conditions. This work was done by the Institute of Soudure in close cooperation with LWF, IPK and WorldAutoSteel members’ and other manufacturing facilities. Ten different non-destructive techniques and systems were investigated. These techniques can be complementary, with various levels of costs, with some solutions more technically mature than others. Several techniques proved to be successful in crack detection. In order to aid the production source, techniques must not only detect but also characterize cracks to determine intensity and the effect on joint strength. Further work is required to achieve production-level characterization.

The study report provides detailed technical information concerning the experimental findings and performances of each technique/system and the possible application cost of each. Table 1 shows a summary of results:

Table 1: Summary of NDT: LME Detection and Characterization Methods

Preventing LME

Suitable measures should always be adapted to the specific use case. Generally, the most effective measures for LME prevention or mitigation are:

- Avoidance of excessive heat input (e.g. excess welding time, current).

- Avoidance of sharp edges on spot welding electrodes; instead use electrodes with larger working plane diameter, while not increasing nugget-size.

- Employing extended hold times to allow for sufficient heat dissipation and lower surface temperatures.

- Avoidance of improper welding equipment (e.g. misalignments of the welding gun, highly worn electrodes, insufficient electrode cooling)

In conclusion, a key finding of this study is that LME cracks only occurred in the study experiments when there were deviations from proper welding parameters and set-up. Ensuring these preventive measures are diligently adhered to will greatly reduce or eliminate LME from the manufacturing line. For an in-depth review of the study and its findings, you can download a copy of the full report at worldautosteel.org.

LME Study Authors

The LME study authors were supported by a committed team of WorldAutoSteel member companies’ Joining experts, who provided valuable guidance and feedback.

Related Articles: More on this study in previous AHSS Insights blogs:

Journal Publications:

- Julian Frei, Max Biegler, Michael Rethmeier, Christoph Böhne & Gerson Meschut (2019) Investigation of liquid metal embrittlement of dual phase steel joints by electro-thermomechanical spot-welding simulation, Science and Technology of Welding and Joining, 24:7, 624-633, DOI: 10.1080/13621718.2019.1582203

- Christoph Böhne, Gerson Meschut, Max Biegler, Julian Frei & Michael Rethmeier (2020) Prevention of liquid metal embrittlement cracks in resistance spot welds by adaption of electrode geometry, Science and Technology of Welding and Joining, 25:4, 303-310, DOI: 10.1080/13621718.2019.1693731

-

Auto/Steel Partnership LME Testing and Procedures

Back To Top