Blog, homepage-featured-top, main-blog

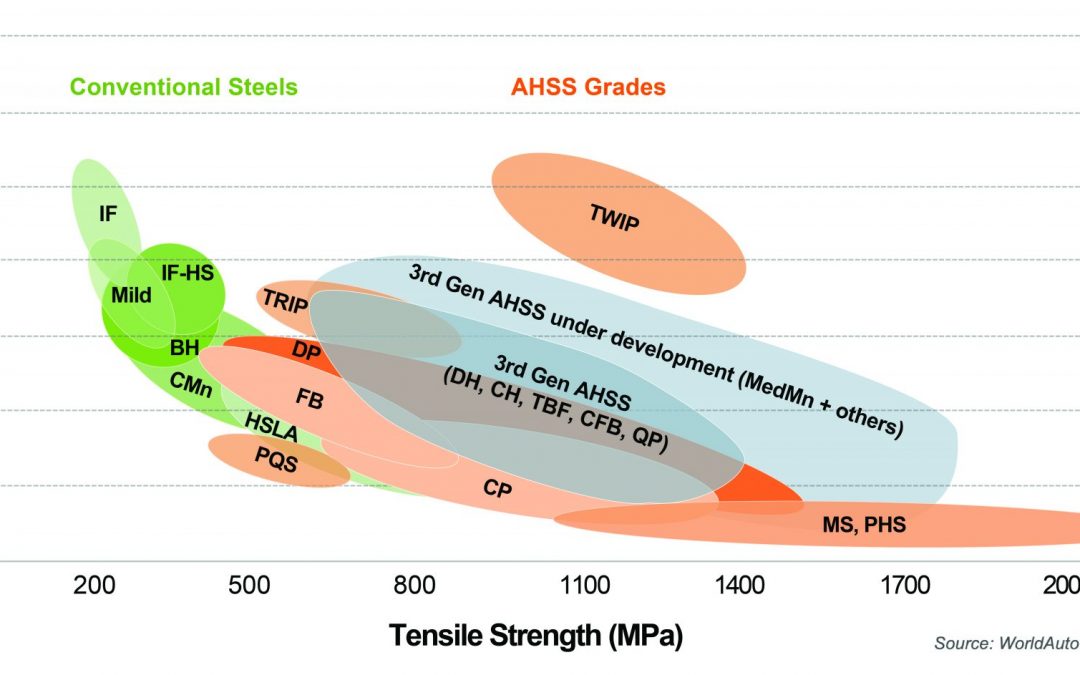

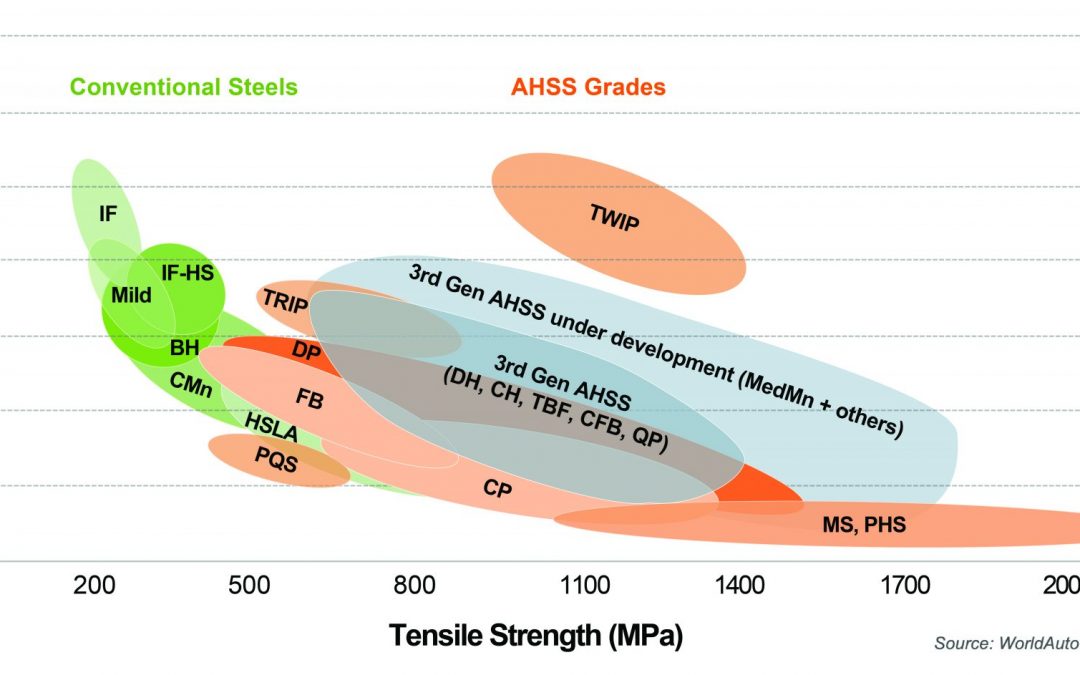

Bubble chart. Banana diagram. Steel strength ductility diagram—it’s been called a lot of things over the years. But the 2021 chart shown in Figure 1 is the subject of hundreds of requests for use we receive from engineers and students all over the world and appears in thousands of presentations and papers. Because of that, we periodically update it to make sure it reflects the most current picture of both commercially available, as well as emerging steel grades. In this blog, we are providing our updated GFD for download as well as definitions of steel classifications, as agreed to by our member companies.

Figure 1: The 2021 Global Formability Diagram comparing strength and elongation of current and emerging steel grades.

Steel Classifications

There are different ways to classify automotive steels. One is a metallurgical designation providing some process information. Common designations include lower-strength steels (interstitial-free and mild steels); conventional high strength steels, such as bake hardenable and high-strength, low-alloy steels (HSLA); and Advanced High-Strength Steels (AHSS) such as dual phase and transformation-induced plasticity steels. Additional higher strength steels include press hardening steels and steels designed for unique applications that have improved edge stretch and stretch bending characteristics.

A second classification method important to part designers is strength of the steel. This document will use the general terms HSLA and AHSS to designate all higher strength steels. The principal difference between conventional HSLA steels and AHSS is their microstructure. Conventional HSLA steels are single-phase ferritic steels with a potential for some pearlite in C-Mn steels.

AHSS are primarily steels with a multiphase microstructure containing one or more phases other than ferrite, pearlite, or cementite – for example martensite, bainite, austenite, and/or retained austenite in quantities sufficient to produce unique mechanical properties. Some types of AHSS have a higher strain hardening capacity resulting in a strength-ductility balance superior to conventional steels. Other types have ultra-high yield and tensile strengths and show a bake hardening behavior.

What are 3rd Gen Steels?

Third Generation, or 3rd Gen, AHSS builds on the previously developed 1st Gen AHSS (DP, TRIP, CP, MS, and PHS) and 2nd Gen AHSS (TWIP), with global commercialization starting around 2020. Third Gen AHSS are multi-phase steels engineered to develop enhanced formability as measured in tensile, sheared edge, and/or bending tests. Typically, these steels rely on retained austenite in a bainite or martensite matrix and potentially some amount of ferrite and/or precipitates, all in specific proportions and distributions, to develop these enhanced properties.

Graphical Presentation

Generally, elongation (a measure of ductility) decreases as strength increases. Plotting elongation on the vertical axis and strength on the horizontal axis leads to a graph starting in the upper left (high elongation, lower strength) and progressing to the lower right (lower elongation, higher strength). When considering conventional steels and the first generation of advanced high strength steels, this shape led to the colloquial description of calling this the banana diagram.

With the continued development of advanced steel options, it is no longer appropriate to describe the plethora of options as being in the shape of a banana. Instead, with new grades filling the upper right portion of Figure 1, perhaps it is more accurate to describe this as the football diagram as the options now start to fall into the shape of an American or Rugby Football. Officially, it is known as the steel Global Formability Diagram.

Even this approach has its limitations. Elongation is only one measure of ductility. Other ductility parameters are increasingly important with AHSS grades, such as hole expansion and bendability. There are several other approaches that have been proposed by experts around the world. Have a look at our Defining Steels article, from which this article was drawn, to learn more about them. You will also find within Defining Steels a detailed explanation of the nomenclature used throughout the Guidelines to define steels. If you have questions, please use the Comments tool below or on the Defining Steels page.

Download the GFD

Because of its popularity, we provide high resolution image files of the GFD here for your download and use. Please source it “Courtesy of WorldAutoSteel” in your papers and presentations. We are happy for you to use it. If you require our signed permission, please write us at steel@worldautosteel.org. We’ll respond quickly.

* The Guidelines use the general terms HSLA and AHSS to designate all higher strength steels.

Citations

Citation:

M-66. M. Mazar Atabaki, J. Ma, W. Liu, R. Kovacevic, “Pore formation and its mitigation during hybrid laser/arc welding of advanced high strength steel”, Materials & Design, Volume 67, 2015, Pages 509-521, ISSN 0261-3069, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matdes.2014.10.072.

Arc Welding

This is a summary of a paper of the same title, authored by K. Májlinger, E. Kalácska, and P. Russo Spena, used by permission.M-65

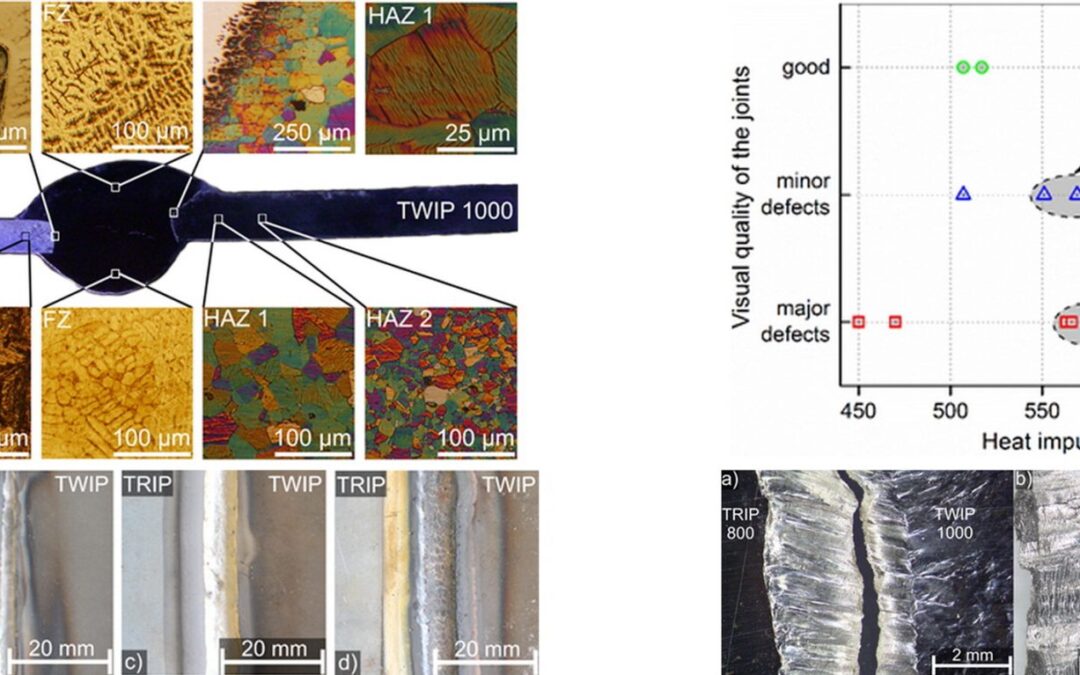

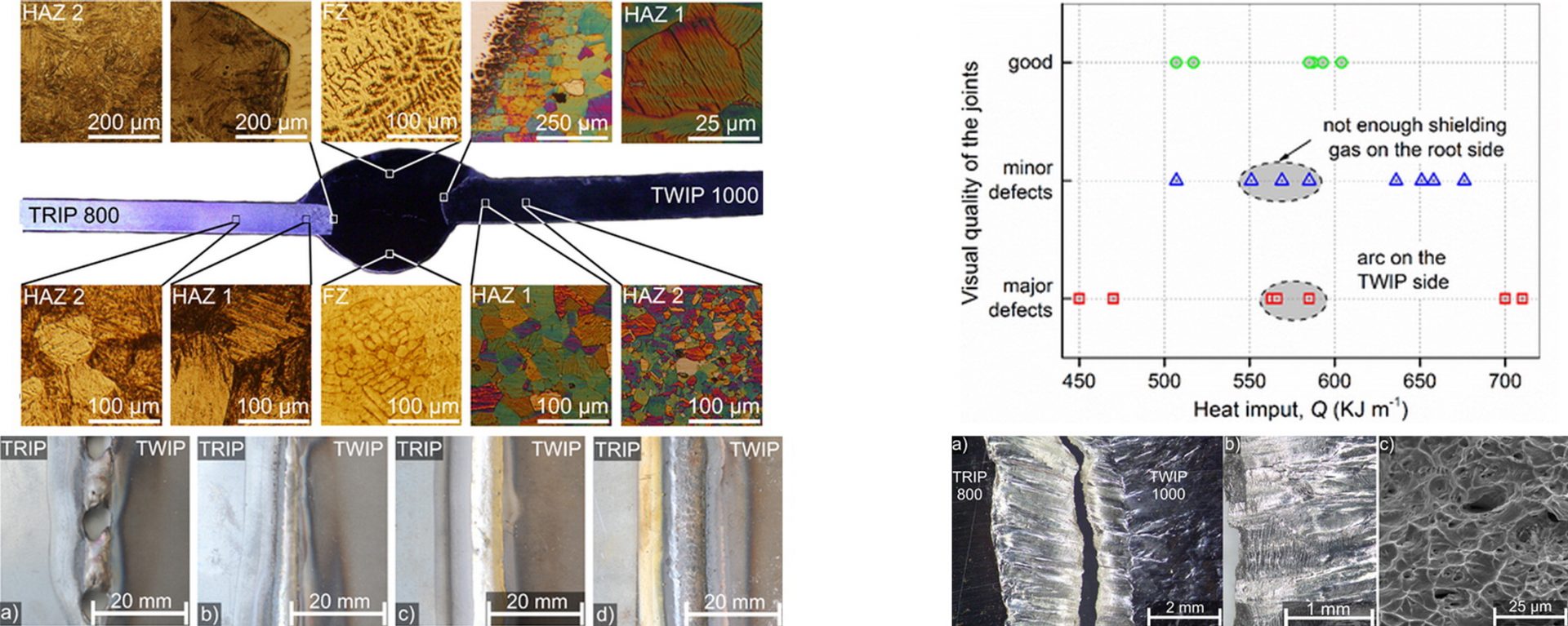

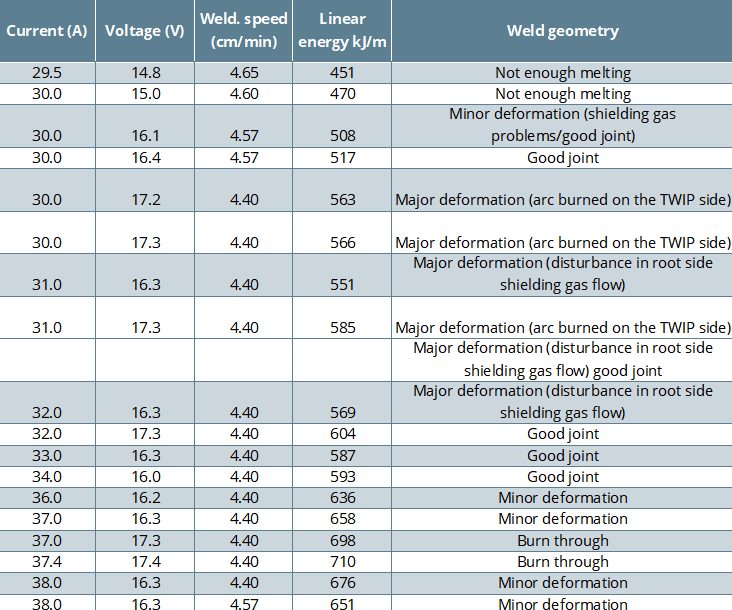

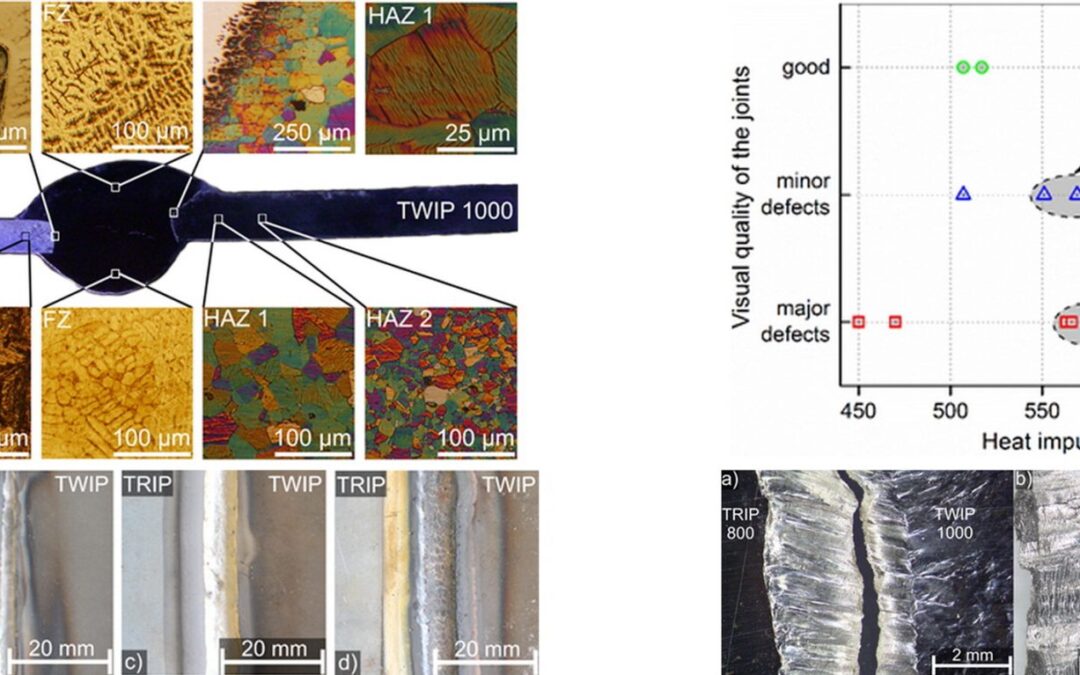

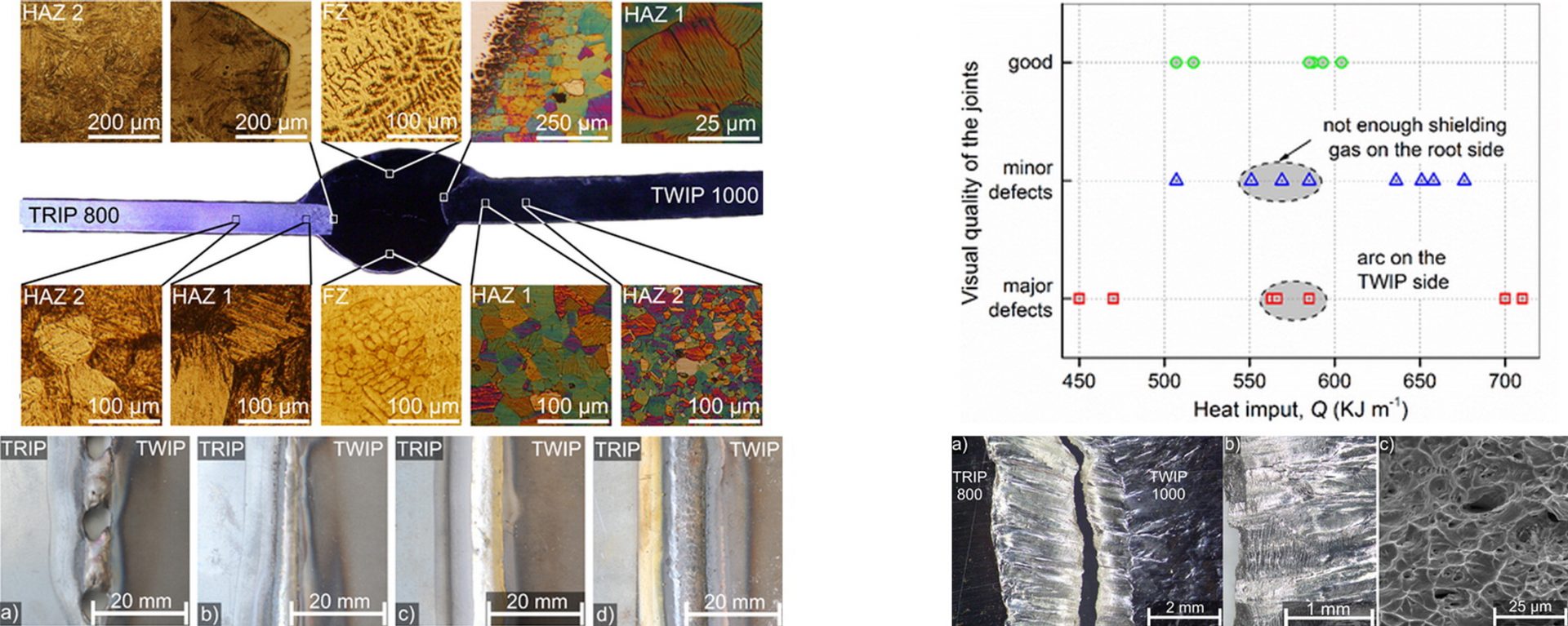

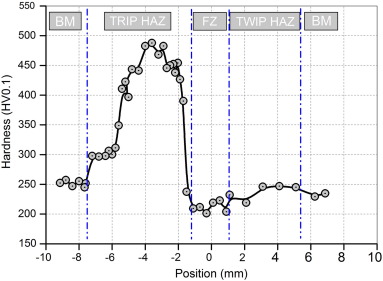

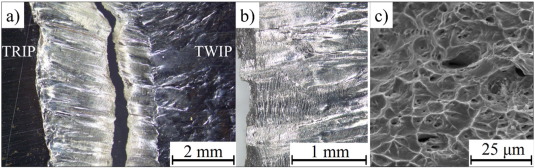

Researchers at the Budapest University of Technology and Economics and the Free University of Bozen-Bolzano tested gas metal arc welding (GMAW) of dissimilar Advanced High-Strength Steel (AHSS) sheets.M-65 The test pieces were 100 x 50 mm samples of 1.4 mm TWIP (TWIP1000) and 0.9 mm TRIP (HCTC800T) sheet steels were welded in a lap joint configuration with 0.8 mm diameter AWS ER307Si austenitic stainless steel wire to determine appropriate GMAW parameters for good quality welds. Quality was determined by external appearance, microstructure, and mechanical properties. Good welds were achieved with linear heat inputs (Q) with ranges from 500-650 kJ/m. The only fractures that occurred appeared within the weld bead by ductile failure modes. The HAZ of the TWIP steel showed grain coarsening and the HAZ of the TRIP steel experienced microstructural changes relative to the distance from the fusion boundary. The ultimate tensile strength (UTS) varies between 73%-84% of the weaker of the two steels.

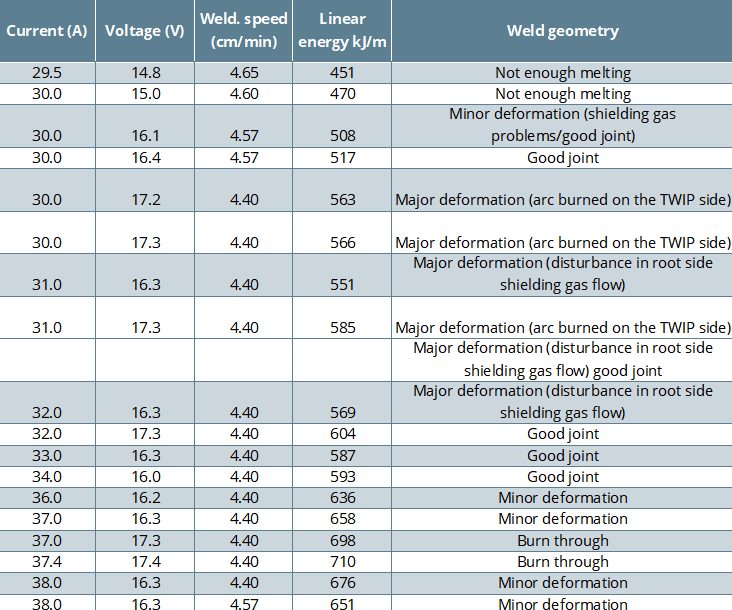

Welding was conducted with an automated linear drive system with pure Argon (99.996% Ar) shielding gas at 10L/min. Wire feed rates were approximately 3.5 m/min with Direct Current Electrode Positive (DCEP) polarity. Changes in current, voltage, weld speed, and the resulting linear energy are compared in Table 1.

Figure 1: Overview of Dissimilar AHSS GMAW Welding.M-65

Table 1: Results of the preliminary welding tests in terms of TWIP-TRIP joint quality.M-65

After welding, transverse sections were cut from the welds and etched to show the microstructure. Vickers hardness testing was conducted on the weld samples based on the ASTM E384 standard. Tensile tests were performed on the samples according to the EN ISO 6892-1 standard. Tests were also conducted on unwelded TWIP and TRIP steels for comparison. Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) examinations were made of fracture surfaces to determine failure modes and examine for microscopic weld defects.

The study concluded that dissimilar welds between AHSS steels with the GMAW process can be achieved with consistent results desired for automotive applications.

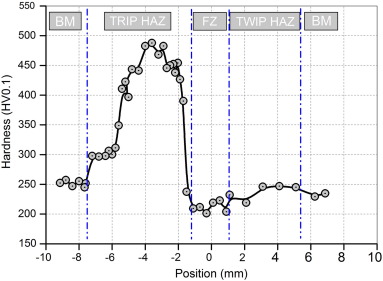

Figure 2: Vickers Hardness Across Weldment.M-65

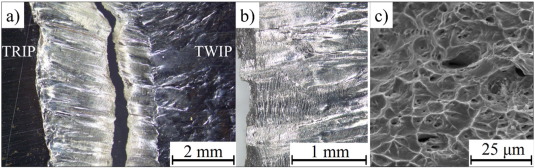

Figure 3: Ductile Failure in the fragile zones (FZ).M-65

Citations

Citation:

M-65. K. Májlinger, E. Kalácska, P. Russo Spena, “Gas metal arc welding of dissimilar AHSS sheets”, Materials & Design, Volume 109, 2016, Pages 615-621, ISSN 0264-1275, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matdes.2016.07.084

Blog, homepage-featured-top, main-blog

Additive Manufacturing (AM) has been associated with the future of manufacturing since its inception. While it does hold several advantages in complex geometries and low-volume production, modern AM systems have yet to make significant in-roads with direct-print parts in industries like automotive manufacturing which are characterized by large volumes of relatively large metal parts. With typical volumes of 1,000+ vehicles per line per day, the required throughput of automotive factory lines outstrips what is available in current AM systems. Further, the large volume of parts allows for rapid amortization of capital equipment such as tools, dies, and stamping presses, circumventing one of the primary advantages of AM: reduced per-piece cost. However, if the focus is shifted from direct-print parts to manufacturing the supporting infrastructure, tools and dies, the economic benefits are regained. Using AM to manufacture forming tools for Advanced High-Strength Steels (AHSS) and Press Hardened Steels (PHS) brings the opportunity for reduced tooling lead-time, reduced tooling cost, and optimization of the tools for weight, strength, and thermal management.

Metal AM: Application in Traditional Forming

While AM enables the flexible production of tools with lead-time reduction and minimal economic impactsG-35, W-29, the production cost for the metal AM tools is significantly higher compared to polymer AM tools and, in some cases, metal tools manufactured by conventional methods. However, cost of the AM tools can be mitigated through topology optimization.A-61 With topology optimization, parts with freeform geometry can be designed that are optimized against a specific objective, for example weight, strength, or stiffness. By reducing overall tool material while maintaining strength, build time on the AM system can be reduced, thereby lowering tool cost.

Potential applications of metal AM forming tools are in prototype construction or small series production, e.g. holders, flanges or medium-size adapters and reinforcing plates.S-74 AM methods have also been utilized for insertion of beads or other geometries for reinforcing/increasing the stiffness of tools.L-36 Cost typically prevents metal AM tools from being used in low-volume cold forming applications where the main tool body is printed, however, high wear components and insert applications have demonstrated significant lead-time savings over traditional manufacturing methods.L-36 Metal AM may be considered in cold forming applications where lead-time is at a premium and cost concerns are secondary.

However, in instances where complex internal structures are required, the increased cost of metal AM is outstripped by the benefits it can provide over conventionally manufactured tools. One such example is a metal AM tool for white goods that utilizes high performance stainless steel for the forming surface and less expensive mild steel for the underlying structure. The resulting die, Figure 6, was constructed from less material, reducing overall machining time required to create the finish die surface.P-25

![Figure 6: Metal AM die under construction and after nitriding. [REFERENCE 39]](https://ahssinsights.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/Figure_6ab.svg)

Figure 6: Metal AM die under construction and after nitriding.P-25

Metal AM: Application in Hot Stamping

An important advantage of hot forming is that it requires low-forming loads and enables forming parts with high strength and minimal springback. However, the high temperatures required to form the material and the precise cooling required to ensure desirable component properties necessitate advanced tooling designs.

Bulk materials used for fabricating hot stamping dies require special properties. The tool material must exhibit high tensile strength, hardness, good corrosion resistance, a low thermal expansion coefficient, and high thermal conductivity.N-19 Traditionally, casting and machining are used to manufacture hot stamping tools, however, in recent years AM has gained significant traction due to the design freedom that it offers, especially when it comes to fabricating tools with conformal cooling channels. Reducing porosity is one of the primary remaining challenges to maximizing mechanical properties and achieving good build quality in AM components. Conventionally manufactured hot tool steels demonstrate properties of at least 1300 MPa tensile strength, 50 HRC hardness, 18 J of impact toughness and 22 W/mK of thermal conductivity. Selected AM materials should demonstrate at least these properties in order to be considered a reliable alternative.

Hot stamp tooling with conformal cooling channels has been demonstrated with both Directed Energy Deposition (DED) and and Powder-Bed Fusion (PBF) AM processes. With DED processes, it is possible to attain minimum channel diameters as low as 3 mm and a minimum wall thicknesses of 2 mm. Unlike drilling straight holes, as done with traditional tool manufacturing, it is possible to design and fabricate complex cooling channels inside the die that results in homogeneous temperature distribution within the tool and the stamped parts. The improved temperature distribution leads to lower cycle times in hot stamping and subsequent improvement in process efficiency, reducing overall production costs. DED also has been combined with subtractive processes to create a hybrid manufacturing process.C-21 One example includes hot stamping dies manufactured by machining and additively building inserts with conformal cooling ducts.M-35 As a result, the additively manufactured channels cooled six times faster than the conventional drilled channels. In another example, manufactured injection molds with conformal cooling ducts by combining direct metal rapid tooling and machining.A-62

PBF processes are also used to integrate conformal cooling channels into forging dies and hot stamping tools. Regardless of the AM method, development of the internal network channels can be aided by topology optimization, a tool that offers great flexibility in designing non-intuitive, novel, and complex parts with high performance at reduced material cost.G-36 In addition to optimizing for mechanical objectives, topology optimization can also be defined such that it designs products considering performance criteria across multiple domains such as thermal and mechanical. Such multi-objective topology optimization is a powerful tool in designing metal AM tooling that takes advantage of the optimized thermal and mechanical performance made possible through AM processes.

This is an excerpt of a full Guidelines article entitled, “Additive Manufacturing for Sheet Metal Forming Tools,” which is based on a project conducted in partnership between Honda Development & Manufacturing of America, LLC and The Ohio State University. This excerpt focuses on metal AM in traditional forming and hot stamping, while the full article surveys the use of polymer and metal AM for forming tools and discusses the benefits and challenges with respect to their use in manufacturing AHSS and PHS sheet metal components. Be sure to read the full article for the much more detail.

Many thanks are given the team who contributed the Additive Manufacturing article, from which this blog was excerpted.

|

Ryan Hahnlen, Honda Development & Manufacturing of America, LLC, Raymond, OH |

|

Ben Hoffman, Honda Development & Manufacturing of America, LLC, Raymond, OH |

|

Madhura Athale, Integrated Systems Engineering Department at Ohio State University, Columbus, OH |

|

Taejoon Park, Integrated Systems Engineering Department at Ohio State University, Columbus, OH |

|

Farhang Pourboghrat, Integrated Systems Engineering Department at Ohio State University, Columbus, OH |

|

|