![Martensite]()

1stGen AHSS, AHSS, Steel Grades

Martensitic steels are characterized by a microstructure that is mostly all martensite, but possibly also containing small amounts of ferrite and/or bainite (Figure 1 and 2). Steels with a fully martensitic microstructure are associated with the highest tensile strength – grades with a minimum specified tensile strength of 1700 MPa are commercially available, and higher strength levels are under development.

Figure 1: Schematic of a martensitic steel microstructure. Ferrite and bainite may also be found in small amounts.

Figure 2: Microstructure of MS 950/1200

To create MS steels, the austenite that exists during hot-rolling or annealing is transformed almost entirely to martensite during quenching on the run-out table or in the cooling section of the continuous annealing line. Adding carbon to MS steels increases hardenability and strengthens the martensite. Manganese, silicon, chromium, molybdenum, boron, vanadium, and nickel are also used in various combinations to increase hardenability.

The advent of water quenched lines facilitated the ability to reduce the amount of alloying additions, which has an associated benefit of producing a microstructure that is less susceptible to delayed cracking.

These steels are often subjected to post-quench tempering to improve ductility, so that extremely high strength levels can be achieved along with adequate ductility for certain forming processes like Roll Forming.

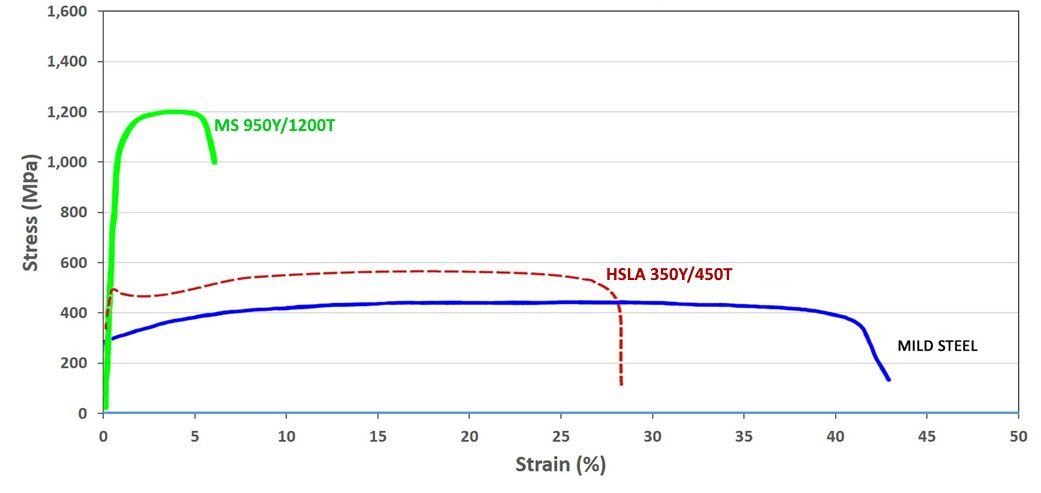

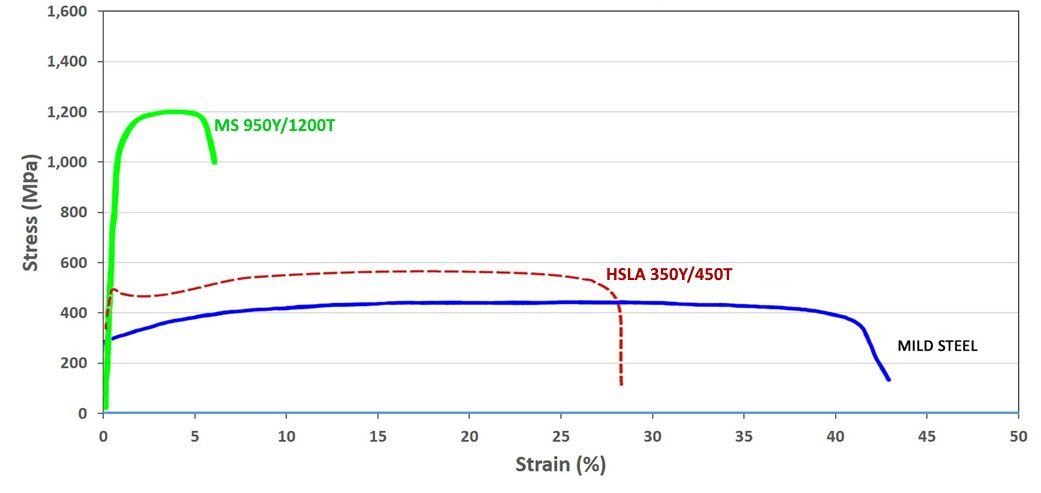

Figure 3 shows MS950/1200 compared to HSLA. Engineering and true stress-strain curves for MS steel grades are presented in Figures 4 and 5.

Figure 3: A comparison of stress strain curves for mild steel, HSLA 350/450, and MS 950/1200.

Figure 4: Engineering stress-strain curves for a series of MS steel grades.S-5 Sheet thicknesses: 1.8 mm to 2.0 mm.

Figure 5: True stress-strain curves for a series of MS steel grades.S-5 Sheet thicknesses: 1.8 mm to 2.0mm.

In addition to being produced directly at the steel mill, a martensitic microstructure also can be developed during the hot stamping of press hardening steels.

Examples of current production grades of martensitic steels and typical automotive applications include:

| MS 950/1200 |

Cross-members, side intrusion beams, bumper beams, bumper reinforcements |

| MS 1150/1400 |

Rocker outer, side intrusion beams, bumper beams, bumper reinforcements |

| MS 1250/1500 |

Side intrusion beams, bumper beams, bumper reinforcements |

Some of the specifications describing uncoated cold rolled 1st Generation martensite steel (MS) are included below, with the grades typically listed in order of increasing minimum tensile strength. Different specifications may exist which describe hot or cold rolled, uncoated or coated, or steels of different strengths. Many automakers have proprietary specifications which encompass their requirements.

- ASTM A980M, with Grades 130 [900], 160 [1100], 190 [1300], and 220 [1500]A-23

- VDA 239-100, with the terms CR860Y1100T-MS, CR1030Y1300T-MS, CR1220Y1500T-MS, and CR1350Y1700T-MSV-3

- SAE J2745, with terms Martensite (MS) 900T/700Y, 1100T/860Y, 1300T/1030Y, and 1500T/1200YS-18

Case Study: Using Martensitic Steels

as an Alternative to Press Hardening Steel

– Laboratory Evaluations

Martensitic steel grades provide a cold formed alternative to hot formed press hardening steels. Not all product shapes can be cold formed. For those shapes where forming at ambient temperatures is possible, design and process strategies must address the springback which comes with the high strength levels, as well as eliminate the risk of delayed fracture. The potential benefits associated with cold forming include lower energy costs, reduced carbon footprint, and improved cycle times compared with hot forming processes.

Highlighting product forms achievable in cold stamping, an automotive steel Product Applications Laboratory formed a Roof Center Reinforcement from 1.4 mm CR1200Y1470T-MS using conventional cold stamping rather than roll forming, Figure 6. Using cold stamping allows for the flexibility of considering different strategies when die processing which may result in reduced springback or incorporating part features not achievable with roll forming.

Figure 6: Roof Center Reinforcement cold stamped from CR1200Y1470T-MS martensitic steel.U-1

Cold stamping of martensitic steels is not limited to simpler shapes with gentle curvature. Shown in Figure 7 is a Center Pillar Outer, cold stamped using a tailor welded blank containing CR1200Y1470T-MS and CR320Y590T-DP as the upper and lower portion steels.U-1

Figure 7: Center Pillar Outer stamped at ambient temperature from a tailor welded blank containing 1470 MPa tensile strength martensitic steel.U-1

Another characteristic of martensitic steels is their high yield strength, which is associated with improved crash performance. In a laboratory environment, crash behavior is assessed with 3-point bending moments. A studyS-8 determined there was a correlation between sheet steel yield strength and the 3-point bending deformation of hat shaped parts. Based on a comparison of yield strength, Figure 8 shows that CR1200Y1470T-MS has similar performance to hot stamped PHS-CR1800T-MB and PHS-CR1900T-MB at the same thickness and exceeds the frequently used PHS-CR1500T-MB. For this reason, there may be the potential to reduce costs and even weight with a cold stamping approach, providing appropriate press, process, and die designs are used.

Figure 8: Effect of Yield Strength on Bending Moment. The right image shows the typical yield strength range of CR1030Y1300T-MS and CR1200Y1470T-MS as well as typical yield strength values of several Press Hardened Steels.S-8

Case Study: Martensitic Steels as an Alternative to

Press Hardening Steel – Automotive Production Examples

with Springback Mitigation Strategies

Recent years have seen some applications typically associated with press hardening steels transition to a cold stamped martensitic steel, CR1200Y1470T-MS. One such example is found in the third-generation Nissan B-segment hatchback (2020 start of production), which uses 1.2 mm thick CR1200Y1470T-MS as the material for the Second Cross Member Reinforcement.K-45

Using the carbon equivalent formula Ceq=C+Si/30+Mn/20+2P+4S K-45, the newly developed martensitic grade has a carbon equivalent value of 0.28, which is lower than the 0.35 associated with the conventional PHS grade of comparable tensile strength, 22MnB5 (PHS 1500T). The lower carbon equivalent value is expected to translate into easier welding conditions. Furthermore, conventional mechanical trimming and piercing equipment and techniques work with the cold formable martensitic grade, whereas parts formed from press hardening steels typically require laser trimming or other more costly approaches. An evaluation of delayed fracture found no evidence of this failure mode.

Figure 9 highlights this reinforcement, with its placement on the cross member and in the vehicle shown in red. The varying elevation of this part, combined with a non-uniform cross section at the outermost edges, help control springback, but makes roll forming significantly more challenging if that were the cold forming approach.

Figure 9: Cold-Stamped Martensitic Steel with 1500 MPa Tensile Strength used in the Nissan B-Segment Hatchback.K-57

Unbalanced stresses in stamped parts lead to several types of shape fixability issues collectively called springback. In hat shape wall sections, shape fixing beads sometimes referred to as stake beads (see Post Stretch information at this link) mitigate sidewall curl by imparting a tensile stress state on both the top and bottom sheet surfaces and increasing the rigidity. Springback control to limit flexing down the length of longitudinally curved parts requires a different technique. Here, the root cause is the stress difference between the tensile stress at the punch top and the compressive stress at the flange at bottom dead center of the press stroke. Figure 10 presents schematics of the stress distribution when the punch is located at bottom dead center of the press stroke, and the shape fixability issue after load removal.

Figure 10: Cold-Stamped Martensitic Steel With 1500 MPa Tensile Strength Used in the Lexus NXJ-24

A patented approach known as Stress Reverse Forming™T-44 improved dimensional accuracy in the second-generation Lexus NX (2021 start of production) center roof reinforcement, cold stamped from martensitic steel, CR1200Y1470T-MS.J-24 Figure 11 shows different views of this part.

Figure 11: Left Image: Springback Differences Exist in Coils at the Low and High End of the Strength Specification; Right Image: Stress Reverse Forming™ Process Reduces Sensitivity to Springback (Images Adapted from Citation T-29)

Stress Reverse Forming™T-44 uses the principles of the Bauschinger Effect to reverse the direction of the forming stresses during a restrike forming process to achieve a final part closer to the targeted dimensions.T-29 Parts processed with this two-step approach are first over-formed to a smaller radius of curvature than the final part shape. Removing the part from the tool after this first forming step results in the stress distribution seen in the left image in Figure 10. The unique aspect of this approach comes from the second forming step where the tool shape forces the punch top into slight compression while the lower flange is put into slight tension. The tool shape used in this stage contains a slightly greater radius of curvature than the targeted part shape. As shown in Citation T-29, this process appears to be equally effective at all steel strengths.

Without effective countermeasures, springback increases with part strength. Related to this is the springback difference between coils having strength at the lowest and highest ends of the acceptable property range. This can lead to substantial differences in springback between coils completely within specification. However, after using effective countermeasures such as Stress Reverse Forming™ described in Citation T-29, springback differences between coils are minimized, which leads to increased dimensional accuracy and more consistent stamping performance. This phenomenon is shown schematically in Figure 12. Furthermore, unlike conventional stamping approaches, the amount of springback in parts made with this approach does not increase with steel strength.

Figure 12: Left Image: Springback Differences Exist in Coils at the Low and High End of the Strength Specification; Right Image: Stress Reverse Forming™ Process Reduces Sensitivity to Springback (Images Adapted from Citation T-29)

1stGen AHSS, AHSS, Steel Grades

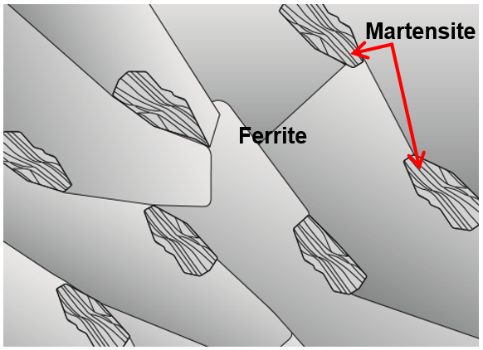

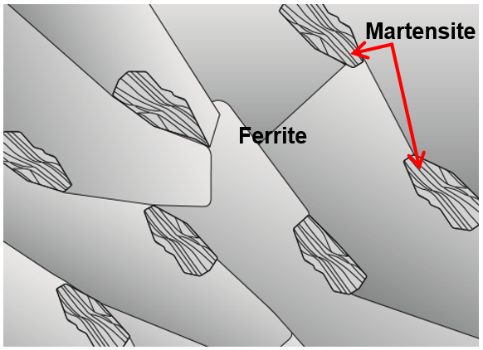

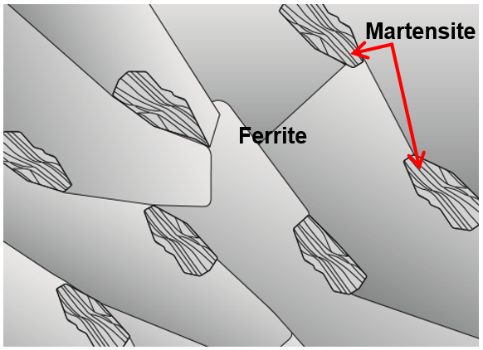

Dual Phase (DP) steels have a microstructure consisting of a ferritic matrix with martensitic islands as a hard second phase, shown schematically in Figure 1. The soft ferrite phase is generally continuous, giving these steels excellent ductility. When these steels deform, strain is concentrated in the lower-strength ferrite phase surrounding the islands of martensite, creating the unique high initial work-hardening rate (n-value) exhibited by these steels. Figure 2 is a micrograph showing the ferrite and martensite constituents.

Figure 1: Schematic of a Dual Phase steel microstructure showing islands of martensite in a matrix of ferrite.

Figure 2: Micrograph of Dual Phase Steel

Hot rolled DP steels do not have the benefit of an annealing cycle, so the dual phase microstructure must be achieved by controlled cooling from the austenite phase after exiting the hot strip mill finishing stands and before coiling. This typically requires a more highly alloyed chemistry than cold rolled DP steels require. Higher alloying is generally associated with a change in welding practices.

In one possible approach, after exiting the last finishing stand of the hot rolling mill, controlled cooling facilitates the nucleation of ferrite. Then a more rapid cooling fast enough to avoid bainite formation is needed to reach the Ms (martensite start) temperature and begin nucleating martensite from the austenite that had not transformed to ferrite.

Continuously annealed cold-rolled and hot-dip coated Dual Phase steels are produced by controlled cooling from the two-phase ferrite plus austenite (α + γ) region to transform some austenite to ferrite before a rapid cooling transforms the remaining austenite to martensite. Due to the production process, small amounts of other phases (bainite and retained austenite) may be present.

Higher strength dual phase steels are typically achieved by increasing the martensite volume fraction. Depending on the composition and process route, steels requiring enhanced capability to resist cracking on a stretched edge (as typically measured by hole expansion capacity) can have a microstructure containing significant quantities of bainite.

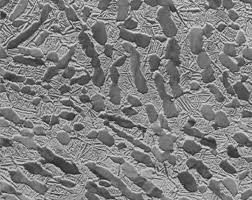

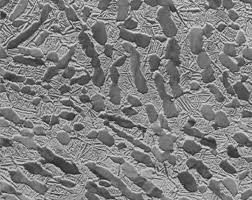

The work hardening rate plus excellent elongation creates DP steels with much higher ultimate tensile strengths than conventional steels of similar yield strength. Figure 3 compares the engineering stress-strain curve for HSLA steel to a DP steel curve of similar yield strength. The DP steel exhibits higher initial work hardening rate, higher ultimate tensile strength, and lower YS/TS ratio than the HSLA with comparable yield strength. Additional engineering and true stress-strain curves for DP steel grades are presented in Figures 4 and 5.

Figure 3: A comparison of stress strain curves for mild steel, HSLA 350/450, and DP 350/600K-1

Figure 4: Engineering stress-strain curves for a series of DP steel grades.S-5, V-1 Sheet thicknesses: DP 250/450 and DP 500/800 = 1.0mm. All other steels were 1.8-2.0mm.

Figure 5: True stress-strain curves for a series of DP steel grades.S-5, V-1 Sheet thicknesses: DP 250/450 and DP 500/800 = 1.0mm. All other steels were 1.8-2.0mm.

The volume fraction, morphology, and distribution of the martensite in the ferrite matrix is responsible for the mechanical properties of dual phase (DP) steels. The intercritical annealing temperature, cooling rate, and alloy content affect the martensite volume fraction in the finished product.

Martensite can have different appearances (morphologies) in the microstructure including needle-like, granular, and equiaxed, and these impact the strength and ductility of DP steels. The most favorable balance of strength and ductility usually is associated with a uniform distribution of equiaxed martensite islands.

These properties influence the hole expansion ratio, which measures the expandability of a sheared edge. The amount of carbon in martensite controls martensite hardness relative to the ferrite, and a greater hardness difference between martensite and ferrite is associated with decreased HER values.

The number of martensite colonies per unit area has a positive correlation with sheared edge stretchability, indicating that there is a greater dispersion of these islands of this high-hardness phase. A more homogeneous microstructure is known to have better HER and sheared-edge formability properties.T-57.

Although dual phase steels are more formable than HSLA steels at the same tensile strength, there is a greater risk of cut edge fractures forming and propagating during stretch flanging. This is due to the hardness difference between the ferrite and martensite phases.

In these steels, micro-voids form at the interface between the soft phase and hard phase at the sheared edge (Figure 6), and can fracture during flanging under tension. Reducing the hardness difference of the microstructural components is one approach to improve edge fracture resistance, which is one of the merits of using complex phase steels.

Figure 6: Microstructure at the punched edge of a DP steel.M-75

DP and other AHSS also have a bake hardening effect that is an important benefit compared to conventional higher strength steels. The extent of the bake hardening effect in AHSS depends on an adequate amount of forming strain for the specific chemistry and thermal history of the steel.

In DP steels, carbon enables the formation of martensite at practical cooling rates by increasing the hardenability of the steel. Manganese, chromium, molybdenum, vanadium, and nickel, added individually or in combination, also help increase hardenability. Carbon also strengthens the martensite as a ferrite solute strengthener, as do silicon and phosphorus. These additions are carefully balanced, not only to produce unique mechanical properties, but also to maintain the generally good resistance spot welding capability. However, when welding the higher strength grades (DP 700/1000 and above) to themselves, the spot weldability may require adjustments to the welding practice.

Dual Phase Steel for Exposed Panels

In recent decades, bake hardenable steels have been a common choice for outer surface panels. Many of these applications center around grades with yield strength of approximately 200 MPa and tensile strength below approximately 400 MPa. Work hardening (strengthening occurring from forming) combined with bake hardening (strengthening from the paint curing cycle during automotive production) usually adds around 70 to 100 MPa to the yield strength, enhancing the dent resistance of these panels.

To further support the lightweighting efforts of the automobile industry, steelmakers have developed dual phase steels with appropriate surface characteristics for exposed panel applications. The benefits of deploying dual phase steels in these applications include a higher yield strength from the steel mill (300 MPa minimum yield strength) and a greater strengthening increase from bake hardening (typically more than 100 MPa) in addition to the work hardening from forming. The strengthening increase allows the automaker to downgauge the sheet thickness to as low as 0.55 mm and maintain adequate dent resistance. More information on the bake hardenability of exposed quality dual phase steels can be found here.

The primary grade in this category can be described as HC300/500DPD+Z, where HC indicates that it is high strength cold rolled steel, 300/500 represents the minimum yield and tensile strength in MPa, DPD is “dual phase deep drawing,” and Z indicates that it is galvanized.

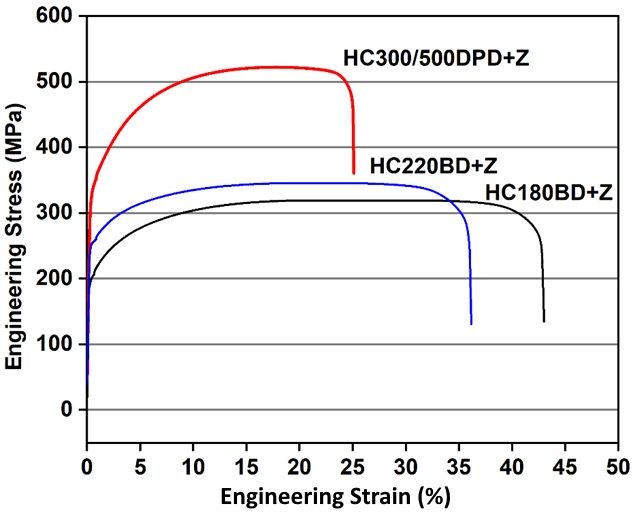

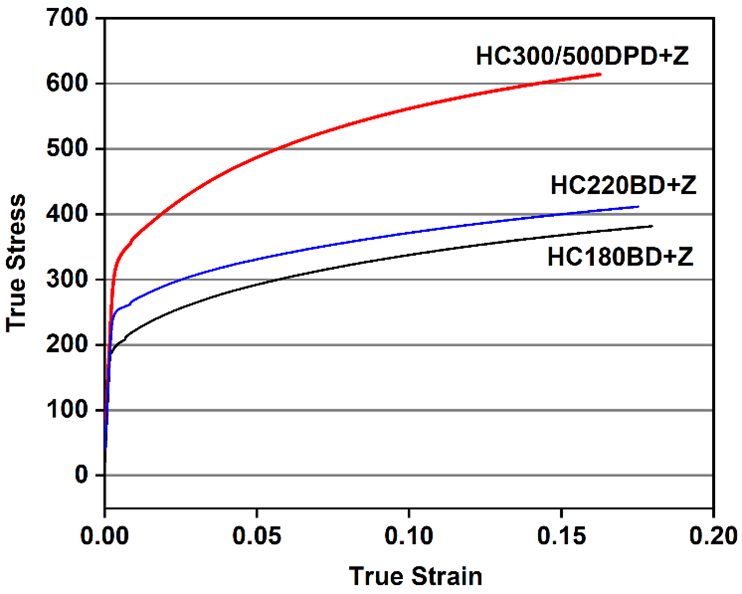

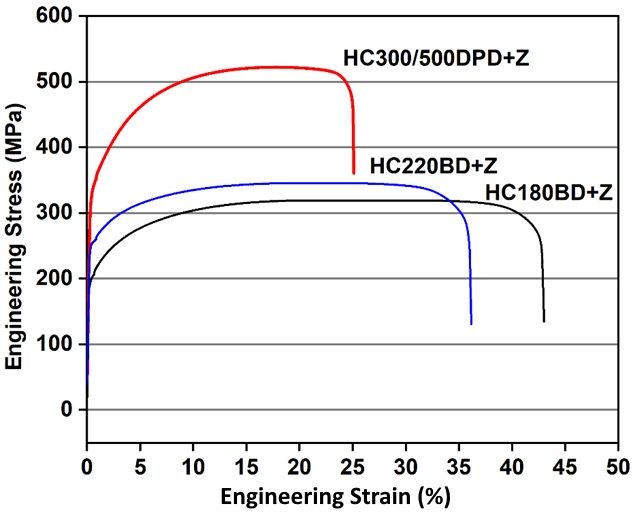

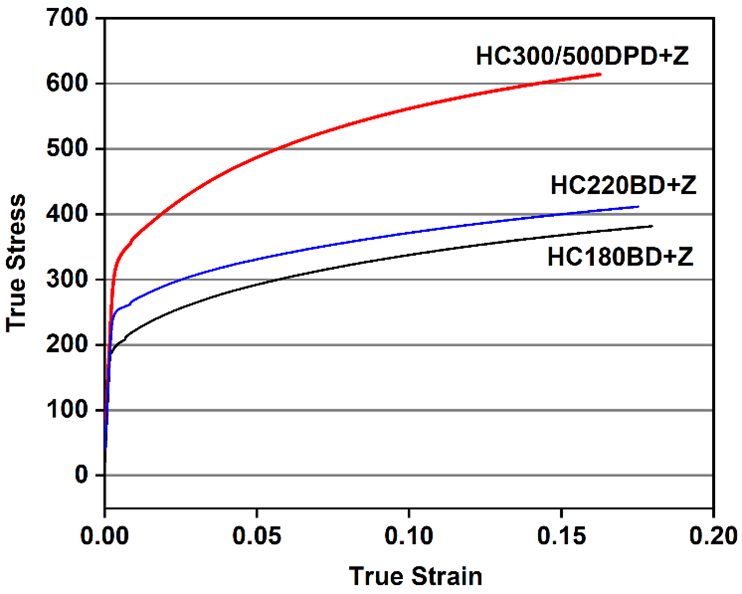

The stress-strain curves of HC300/500DPD+Z are compared with those of common traditional bake hardening grades used for automotive outer skin panels in Figures 7 and 8. The comparison of engineering stress-strain curves are shown in Figure 7, with Figure 8 comparing the true stress-strain curves.

The dual phase steel exhibits a higher tensile strength and greater work hardening (n-value) – especially in the 4% to 6% range that coincides with the strain range associated with stamping automotive outer panels.

Figure 7: Engineering stress-strain curves for 0.6 mm HC300Y/500T-DPD+Z (galvanized 500 DP in red), 0.75 mm HC220BD+Z (galvanized 220 BH in blue), and 0.65 mm HC180BD+Z (galvanized 180 BH in black).

Figure 8: True stress-strain curves for 0.6 mm HC300Y/500T-DPD+Z (galvanized 500 DP in red), 0.75 mm HC220BD+Z (galvanized 220 BH in blue), and 0.65 mm HC180BD+Z (galvanized 180 BH in black).

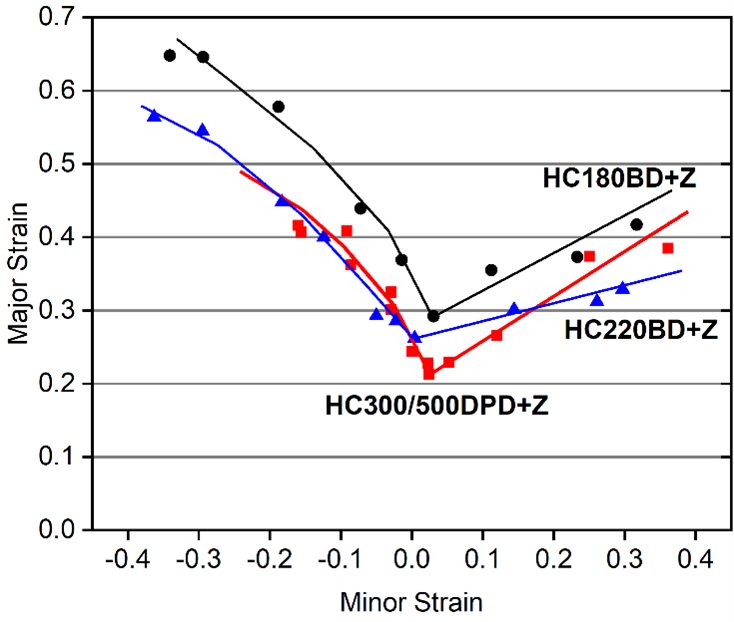

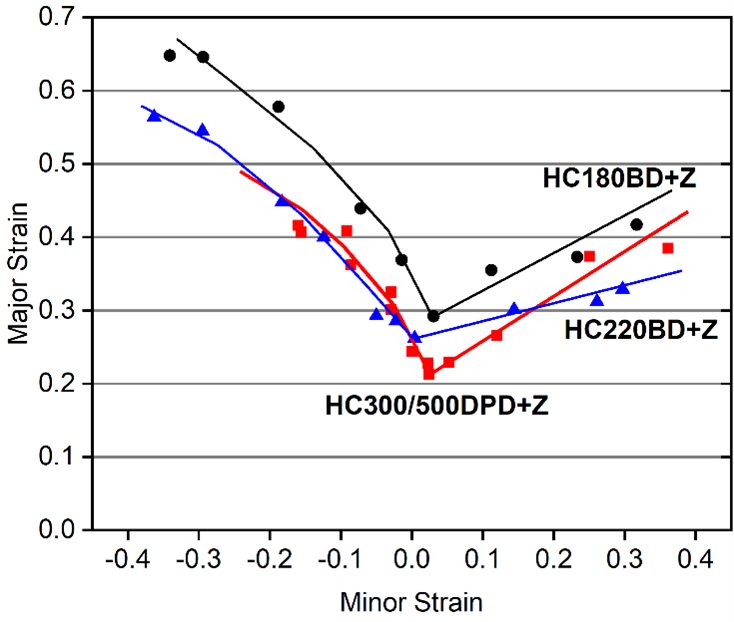

Figure 9 compares the forming limit curve for HC300/500DPD+Z steel to those of the typical bake hardenable grades. The dual phase grade has comparable to slightly less necking resistance than HC220BD+Z, a bake hardenable steel with 220 MPa minimum tensile strength. The necking resistance of HC180BD+Z is greater than both other grades.

Figure 9: Forming limit curves for 0.6 mm HC300Y/500T-DPD+Z (galvanized 500 DP in red), 0.75 mm HC220BD+Z (galvanized 220 BH in blue), and 0.65 mm HC180BD+Z (galvanized 180 BH in black).

While the thickness reduction offered by HC300/500DPD+Z benefits lightweighting, there is also an associated loss of stiffness. This reduced stiffness typically limits how thin automakers will specify for surface panels, rather than steel mill capabilities.

However, the lower stiffness, higher yield strength, and lower formability negatively influence dimensional accuracy and may contribute to welding challenges. Many of these challenges can be addressed virtually using metal forming simulation.

Examples of current production grades of DP steels and typical automotive applications include:

| DP 300/500 |

Roof outer, door outer, body side outer, package tray, floor panel |

| DP 350/600 |

Floor panel, hood outer, body side outer, cowl, fender, floor reinforcements |

| DP 500/800 |

Body side inner, quarter panel inner, rear rails, rear shock reinforcements |

| DP 600/980 |

Safety cage components (B-pillar, floor panel tunnel, engine cradle, front sub-frame package tray, shotgun, seat) |

| DP 700/1000 |

Roof rails |

| DP 800/1180 |

B-Pillar upper |

Some of the specifications describing uncoated cold rolled 1st Generation dual phase (DP) steel are included below, with the grades typically listed in order of increasing minimum tensile strength and ductility. Different specifications may exist which describe hot or cold rolled, uncoated or coated, or steels of different strengths. Many automakers have proprietary specifications which encompass their requirements.

- ASTM A1088, with the terms Dual phase (DP) steel Grades 440T/250Y, 490T/290Y, 590T/340Y, 780T/420Y, and 980T/550YA-22

- EN 10338, with the terms HCT450X, HCT490X, HCT590X, HCT780X, HCT980X, HCT980XG, and HCT1180XD-6

- JIS G3135, with the terms SPFC490Y, SPFC540Y, SPFC590Y, SPFC780Y and SPFC980YJ-3

- JFS A2001, with the terms JSC590Y, JSC780Y, JSC980Y, JSC980YL, JSC980YH, JSC1180Y, JSC1180YL, and JSC1180YHJ-23

- VDA 239-100, with the terms CR290Y490T-DP, CR330Y590T-DP, CR440Y780T-DP, CR590Y980T-DP, and CR700Y980T-DPV-3

- SAE J2745, with terms Dual Phase (DP) 440T/250Y, 490T/290Y, 590T/340Y, 6907/550Y, 780T/420Y, and 980T/550YS-18

1stGen AHSS, 3rdGen AHSS, AHSS, Steel Grades

topofpage

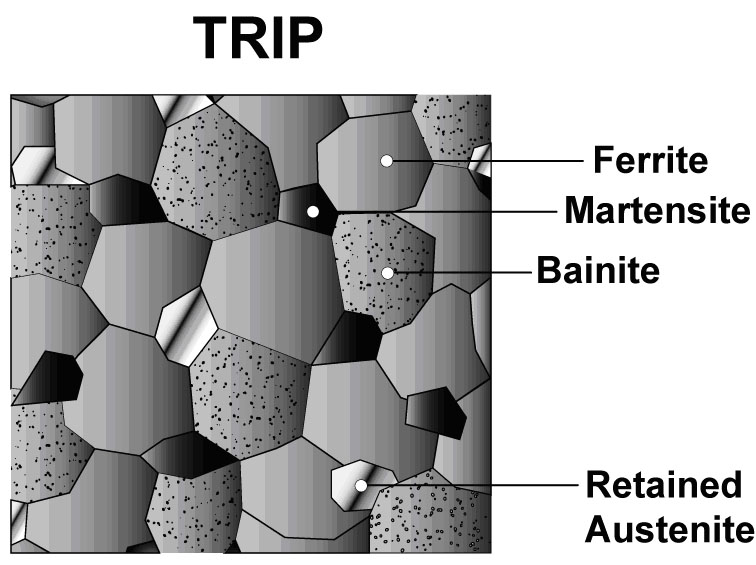

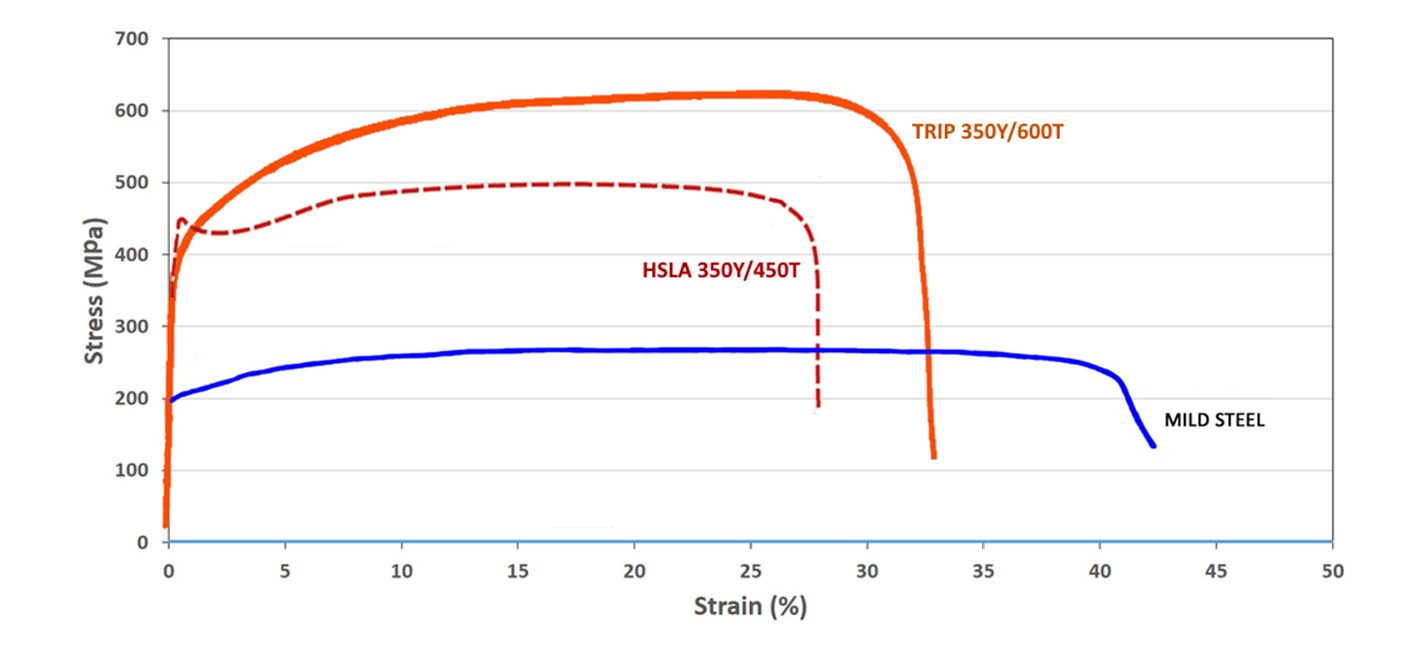

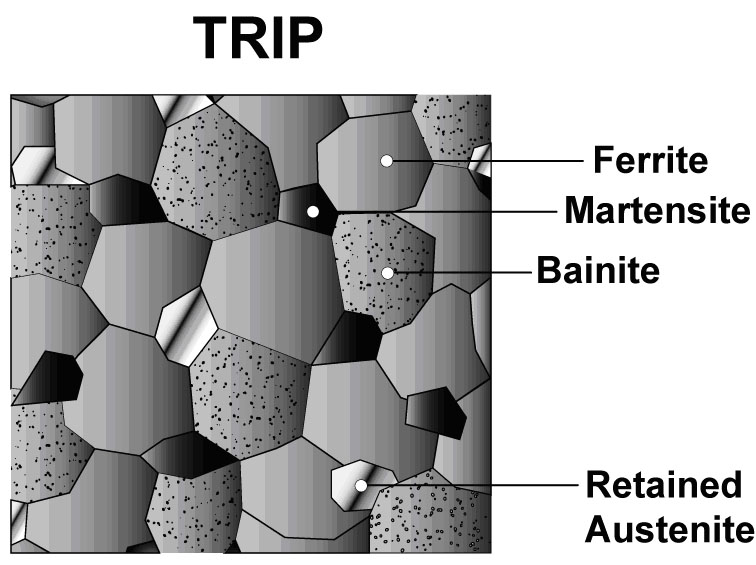

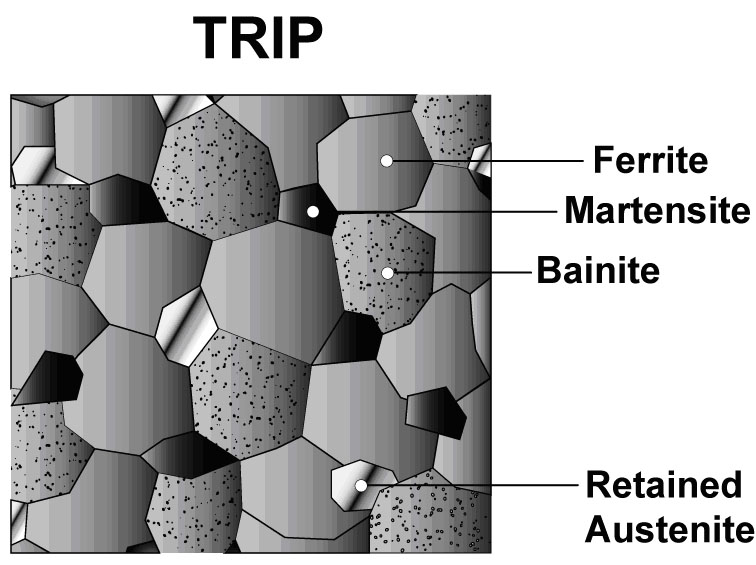

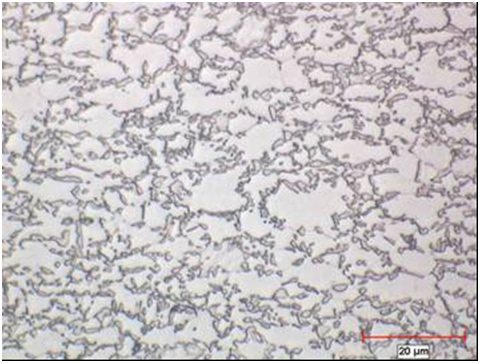

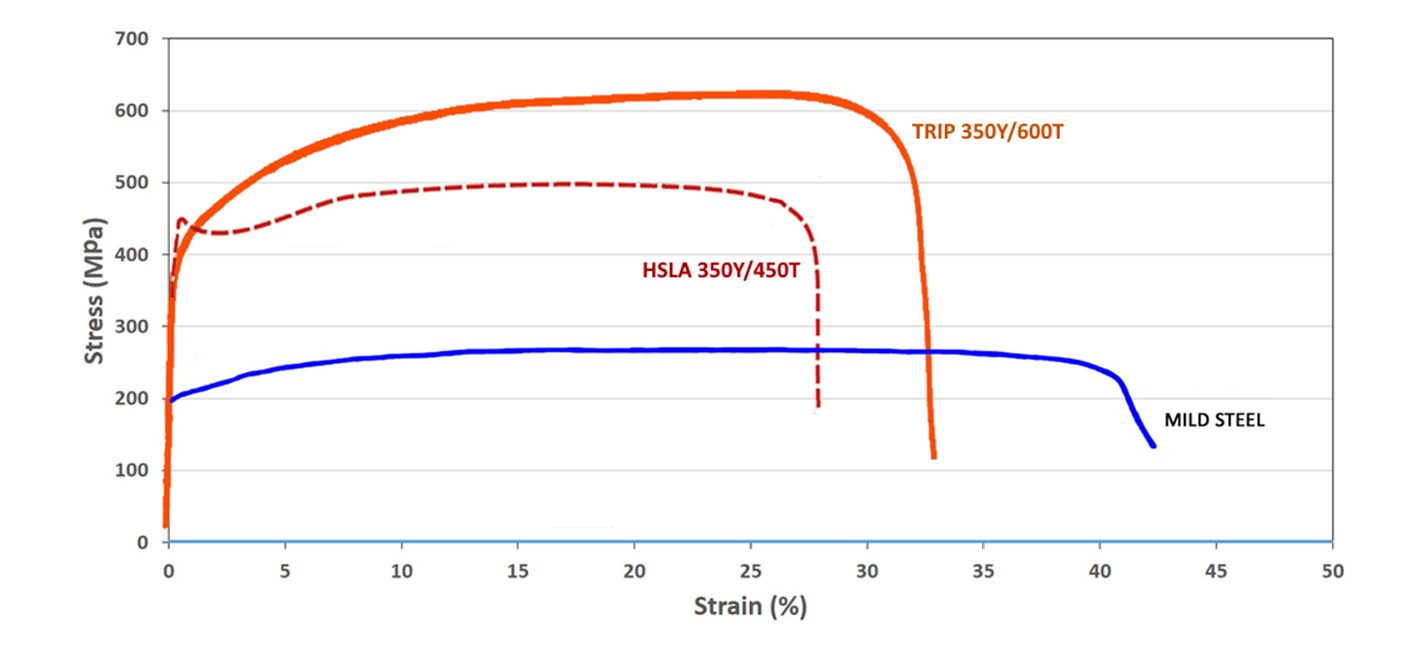

The microstructure of Transformation Induced Plasticity (TRIP) steels contains a matrix of ferrite, with retained austenite, martensite, and bainite present in varying amounts. Production of TRIP steels typically requires the use of an isothermal hold at an intermediate temperature, which produces some bainite. Higher silicon and carbon content of TRIP steels result in significant volume fractions of retained austenite in the final microstructure. Figure 1 shows a schematic of TRIP steel microstructure, with Figure 2 showing a micrograph of an actual sample of TRIP steel. Figure 3 compares the engineering stress-strain curve for HSLA steel to a TRIP steel curve of similar yield strength.

Figure 1: Schematic of a TRIP steel microstructure showing a matrix of ferrite, with martensite, bainite and retained austenite as the additional phases.

Figure 2: Micrograph of Transformation Induced Plasticity steel.

Figure 3: A comparison of stress strain curves for mild steel, HSLA 350/450, and TRIP 350/600.K-1

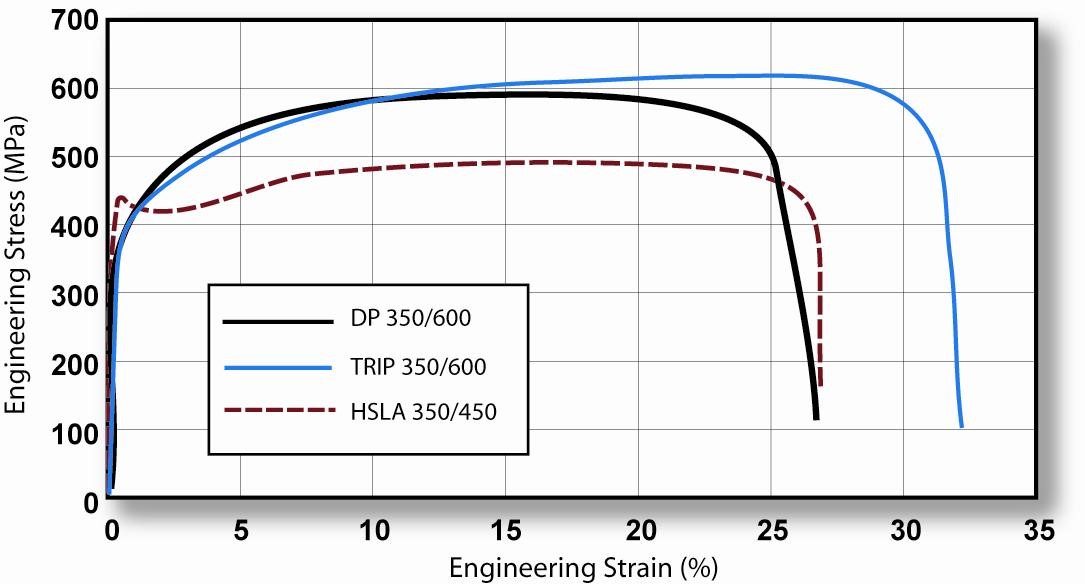

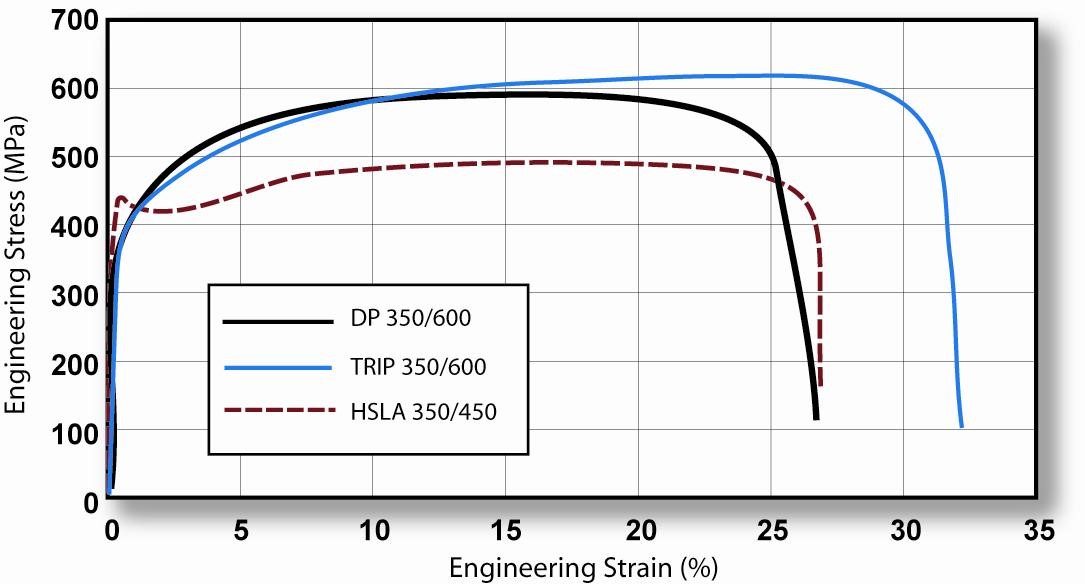

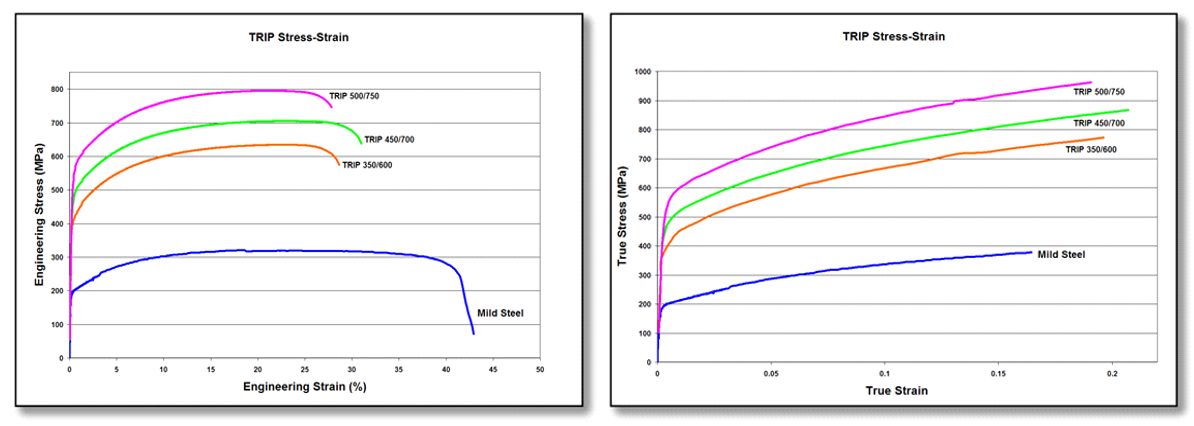

During deformation, the dispersion of hard second phases in soft ferrite creates a high work hardening rate, as observed in the DP steels. However, in TRIP steels the retained austenite also progressively transforms to martensite with increasing strain, thereby increasing the work hardening rate at higher strain levels. This is known as the TRIP Effect. This is illustrated in Figure 4, which compares the engineering stress-strain behavior of HSLA, DP and TRIP steels of nominally the same yield strength. The TRIP steel has a lower initial work hardening rate than the DP steel, but the hardening rate persists at higher strains where work hardening of the DP begins to diminish. Additional engineering and true stress-strain curves for TRIP steel grades are shown in Figure 5.

Figure 4: TRIP 350/600 with a greater total elongation than DP 350/600 and HSLA 350/450. K-1

Figure 5: Engineering stress-strain (left graphic) and true stress-strain (right graphic) curves for a series of TRIP steel grades. Sheet thickness: TRIP 350/600 = 1.2mm, TRIP 450/700 = 1.5mm, TRIP 500/750 = 2.0mm, and Mild Steel = approx. 1.9mm. V-1

The strain hardening response of TRIP steels are substantially higher than for conventional HSS, resulting in significantly improved formability in stretch deformation. This response is indicated by a comparison of the n-value for the grades. The improvement in stretch formability is particularly useful when designers take advantage of the improved strain hardening response to design a part utilizing the as-formed mechanical properties. High n-value persists to higher strains in TRIP steels, providing a slight advantage over DP in the most severe stretch forming applications.

Austenite is a higher temperature phase and is not stable at room temperature under equilibrium conditions. Along with a specific thermal cycle, carbon content greater than that used in DP steels are needed in TRIP steels to promote room-temperature stabilization of austenite. Retained austenite is the term given to the austenitic phase that is stable at room temperature.

Higher contents of silicon and/or aluminum accelerate the ferrite/bainite formation. These elements assist in maintaining the necessary carbon content within the retained austenite. Suppressing the carbide precipitation during bainitic transformation appears to be crucial for TRIP steels. Silicon and aluminum are used to avoid carbide precipitation in the bainite region.

The carbon level of the TRIP alloy alters the strain level at which the TRIP Effect occurs. The strain level at which retained austenite begins to transform to martensite is controlled by adjusting the carbon content. At lower carbon levels, retained austenite begins to transform almost immediately upon deformation, increasing the work hardening rate and formability during the stamping process. At higher carbon contents, retained austenite is more stable and begins to transform only at strain levels beyond those produced during forming. At these carbon levels, retained austenite transforms to martensite during subsequent deformation, such as a crash event.

TRIP steels therefore can be engineered to provide excellent formability for manufacturing complex AHSS parts or to exhibit high strain hardening during crash deformation resulting in excellent crash energy absorption.

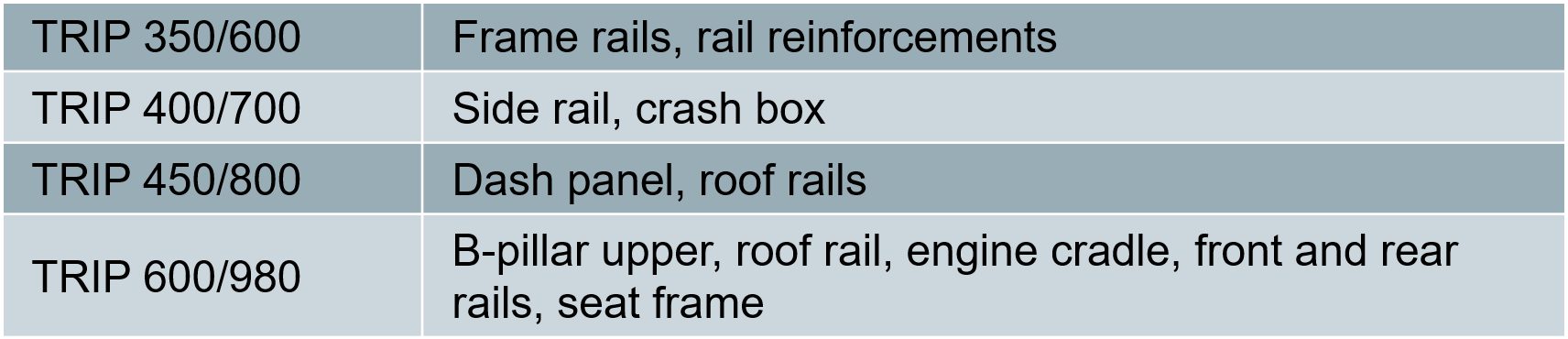

The additional alloying requirements of TRIP steels degrade their resistance spot-welding behavior. This can be addressed through weld cycle modification, such as the use of pulsating welding or dilution welding. Table 1 provides a list of current production grades of TRIP steels and example automotive applications:

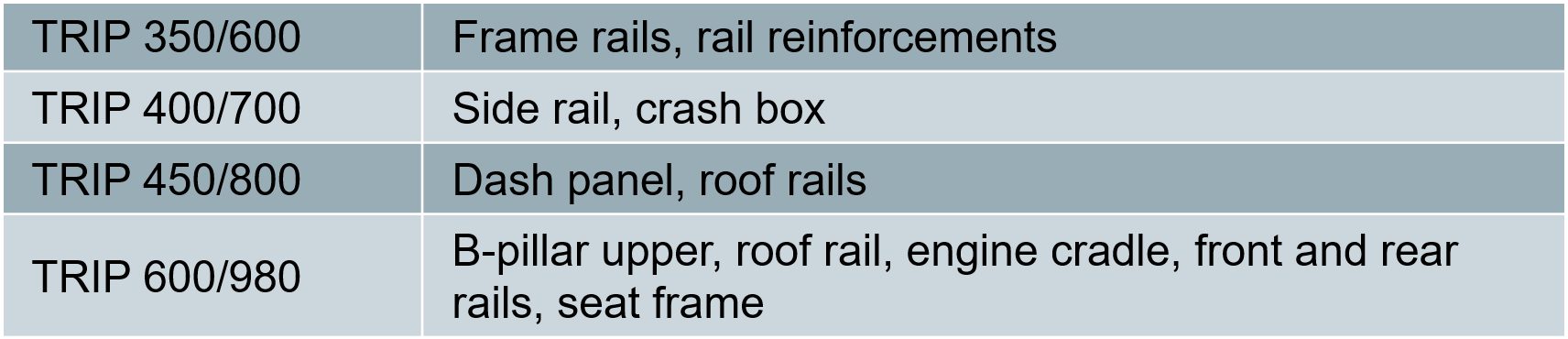

Table 1: Current Production Grades Of TRIP Steels And Example Automotive Applications.

Some of the specifications describing uncoated cold rolled 1st Generation transformation induced plasticity (TRIP) steel are included below, with the grades typically listed in order of increasing minimum tensile strength and ductility. Different specifications may exist which describe hot or cold rolled, uncoated or coated, or steels of different strengths. Many automakers have proprietary specifications which encompass their requirements.

• ASTM A1088, with the terms Transformation induced plasticity (TRIP) steel Grades 690T/410Y and 780T/440YA-22

• JFS A2001, with the terms JSC590T and JSC780TJ-23

• EN 10338, with the terms HCT690T and HCT780TD-18

• VDA 239-100, with the terms CR400Y690T-TR and CR450Y780T-TRV-3

• SAE J2745, with terms Transformation Induced Plasticity (TRIP) 590T/380Y, 690T/400Y, and 780T/420YS-18

Transformation Induced Plasticity Effect

Austenite is not stable at room temperature under equilibrium conditions. An austenitic microstructure is retained at room temperature with the combined use of a specific chemistry and controlled thermal cycle.

Deformation from sheet forming or from crash impact provides the necessary energy to allow the crystallographic structure to change from austenite to martensite. There is insufficient time and temperature for substantial diffusion of carbon to occur from carbon-rich austenite, which results in a high-carbon (high strength) martensite after transformation. Strengthening also occurs from the dislocations formed in the adjacent ferrite required to accommodate the volume increase associated with the austenite-to-martensite transformation.

Transformation to high strength martensite continues as deformation increases, as long as retained austenite (RA) is still available to be transformed. Optimal combinations of strength and ductility are obtained when the retained austenite stability is such that the transformation to martensite occurs gradually with increasing strain.

Alloys capable of the TRIP effect are characterized by a high ductility – high strength combination. Such alloys include 1st Gen AHSS TRIP steels, as well as several 3rd Gen AHSS grades like TRIP-Assisted Bainitic Ferrite, Carbide Free Bainite, and Quench & Partition Steels.

In these grades, increasing the stability of the retained austenite phase delays the austenite-to-martensite transformation to higher strain levels, further promoting formability improvements.

Several factors may promote higher RA stability, including additions of carbon (C) and manganese (Mn). Smaller austenite grains lower the martensite start temperature (Ms) and the number of martensite nucleation sites in each grain, and as such more energy (strain) is needed to start the transformation.

Additions of silicon (Si), chromium (Cr), and aluminum (Al) are also beneficial to achieving the TRIP effect since each of these elements suppress cementite (iron carbide, Fe3C) formation and thereby allows for carbon enrichment of austenite.

However, Mn, Si, Cr, and Al all form oxides on the steel surface that hinder galvanizing and paintability associated with the e-coat layer. Steelmakers typically choose an alloy development and processing strategy which minimizes the detrimental effects of these oxides.

Temperature also has an effect, not only from the paint-bake temperatures of approximately 170 °C, but from galvanizing at close to 500 °C. Citation Z-20 studied the effects of temperature on 0.1%C-5%Mn Medium Manganese steels and found that while tensile strength was relatively independent with temperature, ductility slightly decreases as the temperature is raised from room temperature to 400 °C, but drops off substantially by 500 °C. To retain the formability benefits associated with RA grades, the article recommends galvanizing at temperatures below 400 °C.

In addition to the paint-bake and galvanizing temperatures, adiabatic heating from forming (including shearing and stamping) impact properties. The temperature during forming can be influenced by the starting ambient temperature, the plastic energy dissipation, the latent heat of transformation and by conduction and convection to the environment.M-76

While deforming a metal, most of the energy is dissipated in the form of heat while only a small amount is stored. Austenite-to-martensite transformation kinetics are highly influenced by temperature, and the heating effects associated with mechanically-induced transformation can lead to a severe reduction in ductility.

The temperature rise due to dissipation is not negligible and since the TRIP effect is extremely sensitive to temperature, there is a need for a model to predict this behavior well. Such a model is described in Citation M-76, which reviews that retained austenite stability is a function of several parameters such as temperature; carbon content and alloying elements; austenite grain size and morphology; austenite grain orientation and distribution within the microstructure; and hydrostatic pressure.

Back to the Top

![Martensite]()

1stGen AHSS, AHSS, Steel Grades

Complex Phase (CP) steels combine high strength with relatively high ductility. The microstructure of CP steels contains small amounts of martensite, retained austenite and pearlite within a ferrite/bainite matrix. A thermal cycle that retards recrystallization and promotes Titanium (Ti), Vanadium (V), or Niobium (Nb) carbo-nitrides precipitation results in extreme grain refinement. Minimizing retained austenite helps improve local formability, since forming steels with retained austenite induces the TRIP effect producing hard martensite.F-11

The balance of phases, and therefore the properties, results from the thermal cycle, which itself is a function of whether the product is hot rolled, cold rolled, or produced using a hot dip process. Citation P-18 indicates that galvannealed CP steels are characterized by low yield value and high ductility, whereas cold rolled CP steels are characterized by high yield value and good bendability. Typically these approaches require different melt chemistry, potentially resulting in different welding behavior.

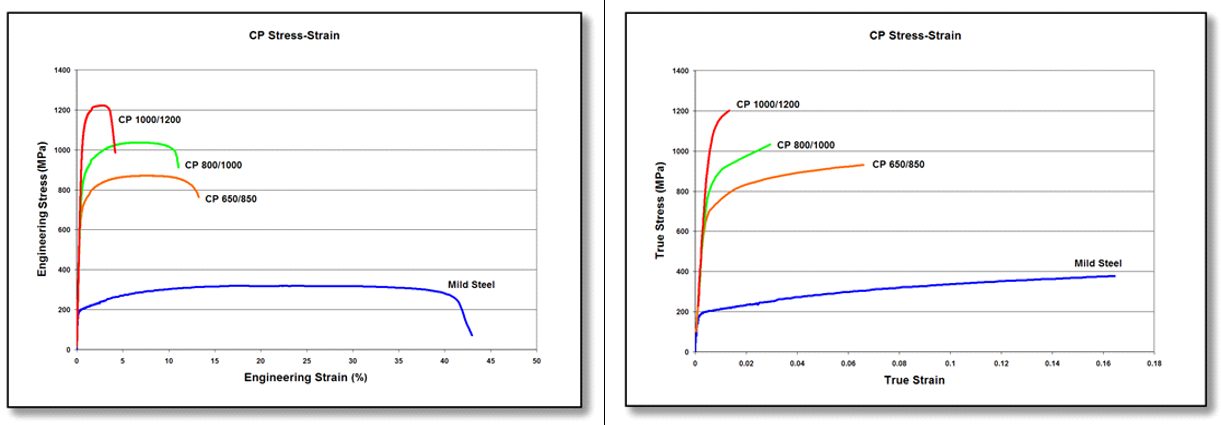

CP steel microstructure is shown schematically in Figure 1, with the grain structure for hot rolled CP 800/1000 shown in Figure 2. The engineering stress-strain curves for mild steel, HSLA steel, and CP 1000/1200 steel are compared in Figure 3.

Figure 1: Schematic of a complex phase steel microstructure showing martensite and retained austenite in a ferrite-bainite matrix.

Figure 2: Micrograph of complex phase steel, HR800Y980T-CP.C-14

Figure 3: A comparison of stress strain curves for mild steel, HSLA 350/450, and CP 1000/1200.

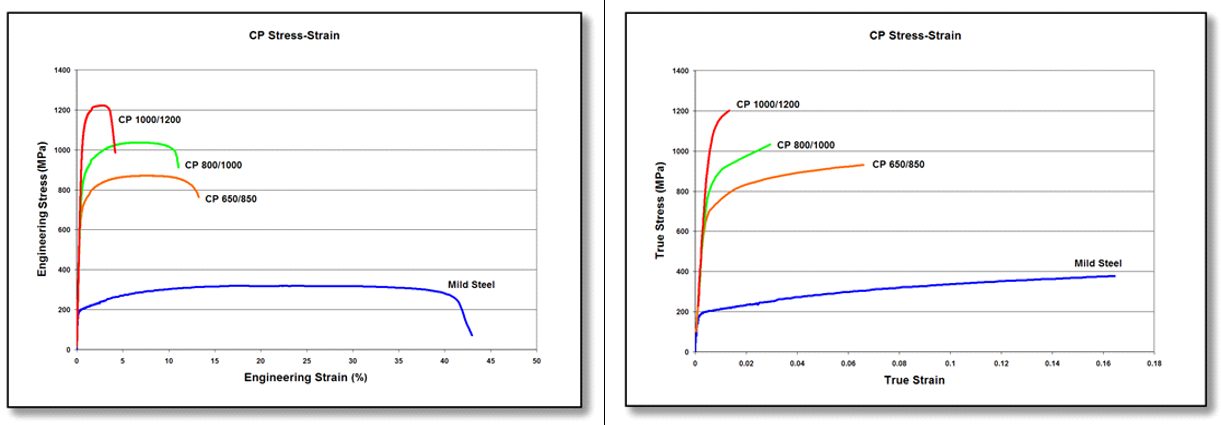

DP and TRIP steels do not rely on precipitation hardening for strengthening, and as a result, the ferrite in these steels is relatively soft and ductile. In CP steels, carbo-nitride precipitation increases the ferrite strength. For this reason, CP steels show significantly higher yield strengths than DP steels at equal tensile strengths of 800 MPa and greater. Engineering and true stress-strain curves for CP steel grades are shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4: Engineering stress-strain (left graphic) and true stress-strain (right graphic) curves for a series of CP steel grades. Sheet thickness: CP650/850 = 1.5mm, CP 800/1000 = 0.8mm, CP 1000/1200 = 1.0mm, and Mild Steel = approx. 1.9mm.V-1

Whereas Dual Phase and TRIP steels excel at stretch forming and deep drawing, they are not as good in bending and cut-edge stretching. For applications needing these characteristics, complex phase steels are a good choice.

Table 1 compares galvannealed Dual Phase and Complex Phase steels having similar tensile strength and elongation as measured in a tensile test. The characteristics with the biggest difference are the yield strength and the hole expansion ratio which is a measure of cut-edge stretchability.

In the VDA-238 bending test, 980 DP exhibited a significant fracture with a bending angle of 67°. The 980 CP showed no fracture at 80°, and was capable of bending to over 100° before fracturing, Figure 5.N-33 The galvannealed 980 CP suppressed crack generation in axial crushing deformation to a much greater degree than the 980 DP.

Figure 5. Bendability of 980 DP (sample A) and 980 CP (sample B).N-33

Examples of typical automotive applications benefitting from these high strength steels with good local formability include frame rails, frame rail and pillar reinforcements, transverse beams, fender and bumper beams, rocker panels, and tunnel stiffeners.

Some of the specifications describing uncoated cold rolled 1st Generation complex phase (CP) steel are included below, with the grades typically listed in order of increasing minimum tensile strength and ductility. Different specifications may exist which describe hot or cold rolled, uncoated or coated, or steels of different strengths. Many automakers have proprietary specifications which encompass their requirements.

- ASTM A1088, with the terms Complex phase (CP) steel Grades 600T/350Y, 780T/500Y, and 980T/700Y A-22

- EN 10338, with the terms HCT600C, HCT780C, and HCT980C D-18

- VDA239-100, with the terms CR570Y780T-CP, CR780Y980T-CP, and CR900Y1180T-CPV-3

![Martensite]()

1stGen AHSS, AHSS, Steel Grades

Ferrite-Bainite (FB) steels are hot rolled steels typically found in applications requiring improved edge stretch capability, balancing strength and formability. The microstructure of FB steels contains the phases ferrite and bainite. High elongation is associated with ferrite, and bainite is associated with good edge stretchability. A fine grain size with a minimized hardness differences between the phases further enhance hole expansion performance. These microstructural characteristics also leads to improved fatigue strength relative to the tensile strength.

FB steels have a fine microstructure of ferrite and bainite. Strengthening comes from by both grain refinement and second phase hardening with bainite. Relatively low hardness differences within a fine microstructure promotes good Stretch Flangable (SF) and high hole expansion (HHE) performance, both measures of local formability. Figure 1 shows a schematic Ferrite-Bainite steel microstructure, with a micrograph of FB 400Y540T shown in Figure 2.

Figure 1: Schematic Ferrite-Bainite steel microstructure.

Figure 2: Micrograph of Ferrite-Bainite steel, HR400Y540T-FB.H-21

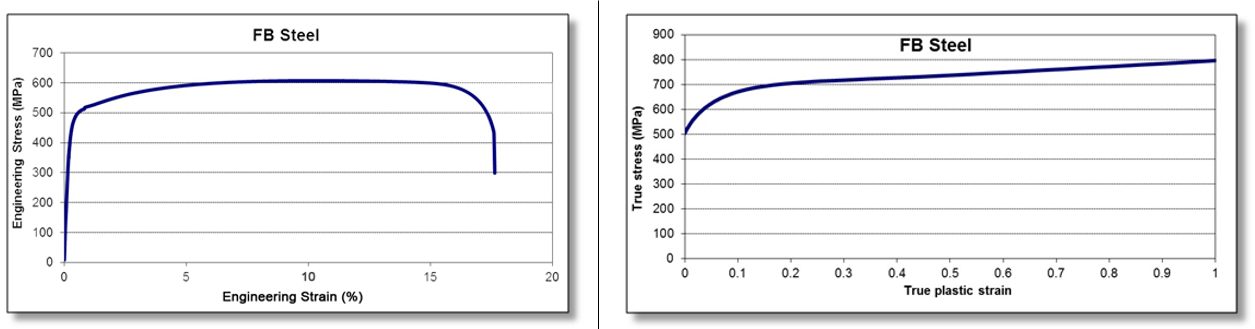

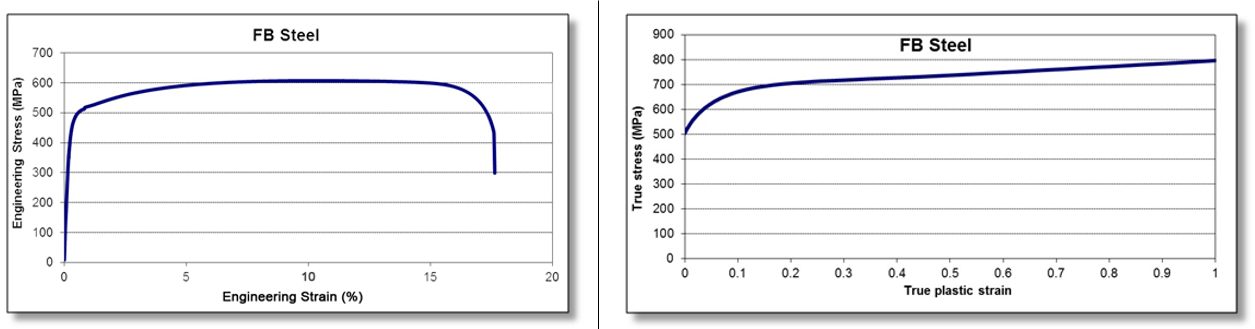

The primary advantage of FB steels over HSLA and DP steels is the improved stretchability of sheared edges as measured by the hole expansion test. Compared to HSLA steels with the same level of strength, FB steels also have a higher strain hardening exponent (n-value) and increased total elongation. Figure 3 compares FB 450/600 with HSLA 350/450 steel. Engineering and true stress-strain curves for FB steel grades are shown in Figure 4.

Figure 3: A comparison of stress strain curves for mild steel, HSLA 350/450, and FB 450/600.

Figure 4: Engineering stress-strain (left graphic) and true stress-strain (right graphic) curve for FB 450/600.T-10

Examples of typical automotive applications benefitting from these high strength highly formable grades include automotive chassis and suspension parts such as upper and lower control arms, longitudinal beams, seat cross members, rear twist beams, engine sub-frames and wheels.

Some of the specifications describing uncoated hot rolled 1st Generation ferrite-bainite (FB) steel are included below, with the grades typically listed in order of increasing minimum tensile strength and ductility. Different specifications may exist which describe uncoated or coated versions of these grades. Many automakers have proprietary specifications which encompass their requirements.

- EN 10338, with the terms HDT450F and HDT580F D-18

- VDA239-100, with the terms HR300Y450T-FB, HR440Y580T-FB, and HR600Y780T-FB V-3

- JFS A2001, with the terms JSC440A and JSC590AJ-23