Citations

Citation:

R-22. P. Rodriguez-Calvillo, J. M. Cabrera, R. G. Thiessen, J. Molina, I. Sabirov, Y. Cui, I. Diego de Calderon, G. Xu, L. Kestens, R. Petrov, D. De Knijf, J. Van Poucke, C. Föjer, A. Di Schino, P. Mecozzi, J. Siestma, and M.J. Santofimia,“New advanced high strength steels by the quenching and partitioning (Q&P) process (NEWQP)”, Grant Agreement RFSR-CT-2011-00017 covering 1 July 2011 to 31 December 2014, Final report to the Directorate-General for Research and Innovation of the European Commission, ISSN 1831-9424, 2015, doi.org/10.2777/104771.

![Non-Linear Strain Paths (Stress-Based FLCs)]()

FLC and FLD

Conventional Forming Limit Curves (FLCs) gained widespread industrial use since being introduced by Dr. Stuart Keeler in the 1960’s. Applications from feasibility analysis to stamping plant troubleshooting use these principles. The strain hardening exponent (n-value) and thickness are inputs into a shortcut to create the curve placement and shape, but this is applicable to only mild steels, conventional High-Strength Steels, and some Advanced High-Strength Steels. Furthermore, this shortcut is an approximation, coming from a best-fit curve generated from data points gathered over multiple grades.

A typical method used in creating most FLCs includes deforming samples of different widths with a 100 mm (4 inch) diameter hemispherical punch – known as the Nakajima method. An alternate approach uses a flat-bottom cylindrical punch, known as the Marciniak method (Figure 1). Independent of the punch shape used, generating FLCs involves measuring the strains resulting from deforming a blank to a formed shape. The conventional FLC plots major strain on the vertical axis against minor strain on the horizontal axis. This FLC applies only to in-plane stretching in linear strain paths, and assumes that there are no through-thickness stress or strain differences. Assessing bendability or cut edge ductility is not possible with this approach.

![Figure 1: Punch Shape Used to Create Forming Limit Curves Result in Through-Thickness Strain Differences Which Influence the Shape and Placement of The FLC [Reference 1]](https://ahssinsights.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/2.3.3.2-Fig1-Domes.svg)

Figure 1: Punch Shape Used to Create FLCs Result in Through-Thickness Strain Differences Which Influence the Shape and Placement of The FLC S-37

Figure 2 compares the FLCs generated by deforming DP980 with the three punch shapes highlighted in Figure 1. Note the higher strains associated with the 50 mm diameter hemispherical punch compared with the strains generated from the 100 mm diameter hemispherical punch. This punch curvature difference impacts the magnitude of the strains that develop through the thickness of the sheet. On samples deformed with a hemispherical punch, the selected strain measurement technique (circle/square grid analysis or Digital Image Correlation, for example) directly measures strains on the outer top surface only, with the middle and inner surface having progressively lower strains as a function of the R/T ratio. A punch or feature with small R/T leads to high strains on the outermost surface. Strains exceeding the FLC on only this outer surface will not lead to necks on the formed panel. Exceeding the FLC through the entire thickness – from the inner surface to the outer surface – must occur for the sample to show a neck.T-17

![Figure 2: FLCs of the same batch of DP980 Showing Dependence on Punch Shape and Curvature [References 1 and 3]](https://ahssinsights.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/2.3.3.2-Fig2-FLC-different.svg)

Figure 2: FLCs of the same batch of DP980 Showing Dependence on Punch Shape and Curvature.S-37, M-15

In addition to the through-thickness strain differences from the punch curvature, the metal flow differences resulting from the punch shapes leads to directional changes in the strain path taken by the deforming metal. A channel drawn part with a hat-shaped cross section in which there are no features like embossments is likely to have a linear strain path. Forming every other engineered stamped part geometry involves some degree of a non-linear strain path (NLSP).

The importance of strain path and deformation history comes from the changes in the forming limit that occur once metal deformation starts. The black curve in Figure 3 shows the FLC for an alloy generated in a conventional manner with as-received metal, assuming a linear strain path. The red curve results from testing the same metal that initially stretched to an equal-biaxial plastic pre-strain of 0.07. In this strain path, substantially less deformation can occur before reaching the forming limit. However, the strain path changes if the local part contour is different, and that strain path results in a different amount of subsequent deformation prior to necking. The magnitude and direction of the shift changes based on the strain and the orientation relative to the rolling direction. Citation S-38 highlights these curves and presents more examples of the effects of different strain paths. The important conclusion is that the amount of deformation that a metal is capable of withstanding prior to necking changes throughout the forming process and depends on the local part shape (among other variables), and cannot be discerned by using only the conventional strain based FLC.

![Figure 3: Experimental FLCs for a linear strain path (in black) and for a bilinear strain path after 0.07 strain in equal biaxial tension in strain space (in red) [Reference 4]](https://ahssinsights.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/2.3.3.2-Figure3-FLC-strainPath.svg)

Figure 3: Experimental FLCs for a linear strain path (in black) and for a bilinear strain path after 0.07 strain in equal biaxial tension in strain space (in red) S-38

Figure 4 shows the strain paths associated with the FLCs presented in Figure 2, with along with a magnified portion of one of the curves. This non-linearity is a characteristic of samples formed with a dome, associated with the sample wrapping around the punch during the initial contact and experiencing a combination of biaxial bending and stretching. Citation M-15 presents a method to correct for strain path effects.

![Figure 4: Strain Path for FLCs shown in Figure 2. A) 100mm diameter flat punch; B) 100mm diameter hemispherical punch; C) 50mm diameter hemispherical punch; and D) Magnified portion of one curve from Figure 4B showing the non-linearity of the strain path [References 1 and 3]](https://ahssinsights.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/2.3.3.2-Figure4-FLC-strainPath.svg)

Figure 4: Strain Path for FLCs shown in Figure 2. A) 100 mm diameter flat punch; B) 100 mm diameter hemispherical punch; C) 50 mm diameter hemispherical punch; and D) Magnified portion of one curve from Figure 4B showing the non-linearity of the strain path.S-37, M-15

Accounting for tool contact pressure is critical as well, since pressure through the sheet thickness suppresses the onset of necking. Applying this compensated FLC in simulation or in hands-on analysis parts analysis requires modification for the unique characteristics of each part, with appropriate adjustments for local curvature, contact pressure and deformation history. Citations S-37 and M-15 detail methods to compensate for the effects of strain path, curvature, and tool pressure. Figure 5 shows that after incorporating these corrections, the curves condense to one shape independent of the variables used.

![Figure 5: As-generated FLCs compared with FLCs after strain path, curvature, and tool contact pressure corrections [References 1 and 3]](https://ahssinsights.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/2.3.3.2_5.jpg)

Figure 5: As-generated FLCs compared with FLCs after strain path, curvature, and tool contact pressure corrections.S-37, M-15

In summary, FLCs generated from relatively similar simple tools are sensitive to small differences in R/T ratio, incorporation of tool contact pressure, and deviations from a linear strain path. By comparison, engineered stampings require substantially more complex tool shapes with differing degrees of curvature, tool contact pressure, and strain paths all within one part. These complex part shapes contribute to an even wider variation in the yield surface and hardening mechanisms important for simulation, and impacts predictions of formability, springback, and stress analysis.

A common requirement during tooling buyoff – where all strains need to be below the FLC by at least a certain amount called the safety margin – magnifies these challenges. AHSS grades already have low FLCs relative to their lower strength counterparts, so it is critical that the chosen FLC does not further reduce efficient application of these grades. Minimizing sensitivity to the changes in strain path occurring across a complex part requires using a different approach – a FLC with the axes in stress-space rather than the conventional strain-space.

This discussion has centered on conventional strain-based FLCs, which incorporate an assumption of a linear strain path as a flat sheet deforms to the final shape. Stress-based Forming Limit Curves (sFLC or FLSC) are insensitive to deformation history and can be adjusted to reflect the differences in local tool geometry or contact pressure across the stamping. Forming analysis software readily converts conventional FLCs into stress-based units. Figure 6 converts the two strain paths presented in Figure 3 into stress-space, and shows the two experimental stress FLCs generated with different strain paths are independent of the loading history and essentially overlap. Citations S-38, S-39, S-40 and S-41 contain information about stress-based FLCs, as well as their generation and usage.

Figure 6: After converting the conventional FLCs in Figure 3 to stress-space, the experimental stress-based FLCs show no significant differences.S-38

Citation H-20 presents a related method to transition from strain-based to stress-based Forming Limit Curves. The proposed stress-based failure criterion postulates that localized necking occurs when a critical normal stress condition is met. This approach adequately describe the experimental strain-based forming limit data in most evaluated materials, failing only with a 3rd Generation AHSS alloy containing a high percentage of retained austenite. For this grade, the authors speculate that a material model more advanced than the one employed in this study will improve correlation.

Accurate simulation requires accurate and complete inputs, including the full range of metal properties, with correct material flow and hardening models, and an understanding of the conditions that will produce failure. Any shortcuts taken increases the likelihood that simulation will not fully match reality for all materials, part shapes, and production processes. A conventional strain-based FLC assumes no effect of part geometry, tool contact pressure, and deformation history – all of which occur on engineered stampings to differing degrees. Analysts should incorporate stress-based FLCs into their simulation with appropriate adjustments to address local geometry and contact pressure to ensure an accurate representation of the metal’s forming characteristics.

For use in the die shop or stamping plant, a growing number of optical systems have built-in features to map strain measurements on to an sFLC. Use caution when employing this approach since these systems measure only the final net strain, and not the strain history as the panel deforms. Proper application involves capturing metal flow from individual breakdown panels and adjusting the FLC accordingly as the panel gets closer to the home position.

Special thanks to Dr. Thomas Stoughton, Technical Fellow, General Motors Research & Development, for assistance in preparing this information.

![Non-Linear Strain Paths (Stress-Based FLCs)]()

Forming Modes

Drawing is the sheet metal forming process where the punch that creates the part shape forces the sheet metal to pull in from the flange area. In contrast with stretch-drawing or stretch forming, little metal thinning occurs in pure drawing. There is not a generally accepted definition for the term “deep drawing,” although some references describe it as when the depth of draw is greater than the diameter.

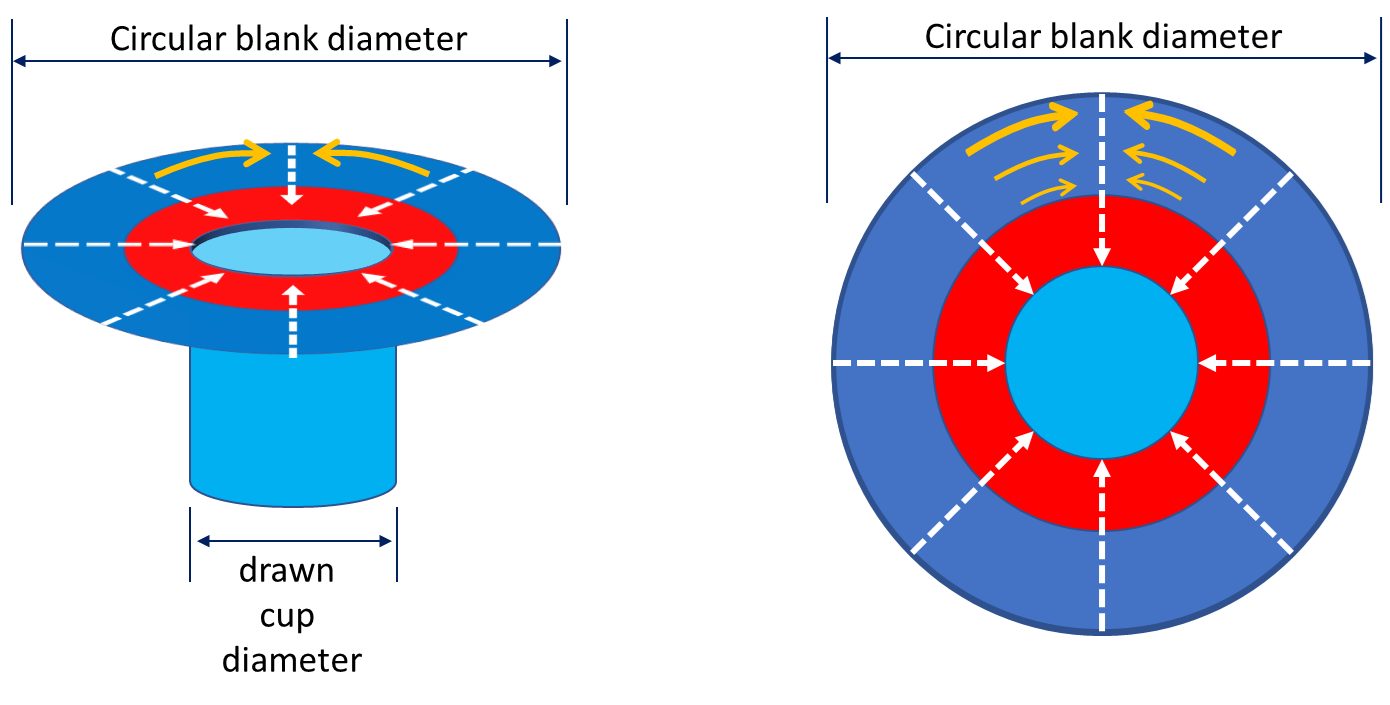

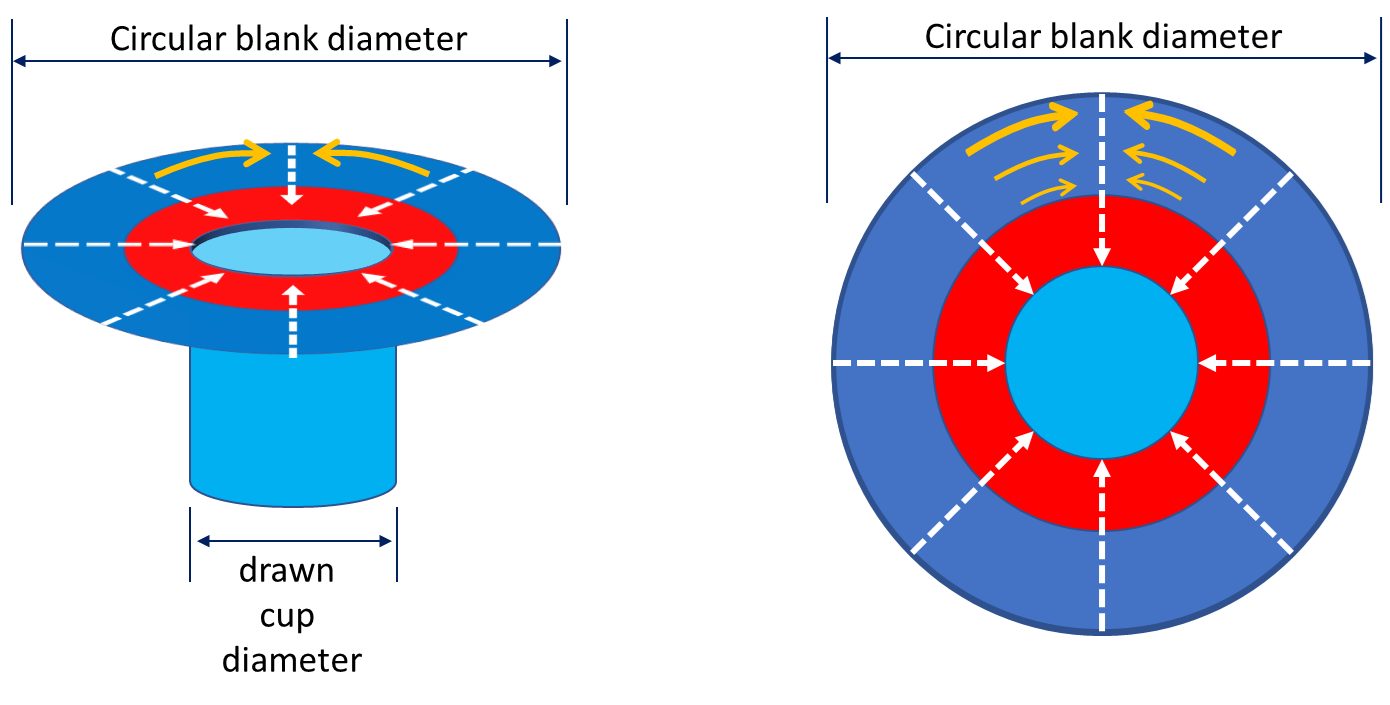

Drawability, or the ability for a sheet metal to be drawn into a cup, is assessed by the cup drawing test to measure the Limiting Draw Ratio, or LDR. Here, a cylindrical punch contacts and then pushes a circular blank into the die (Figure 1). The ratio of the largest blank diameter successfully drawn into a cup to the punch diameter used for drawing is the LDR.

Figure 1: In the cup drawing test, a punch deforms a circular blank into a cylindrical cup. The largest ratio of blank diameter to punch diameter successfully drawn into a cup is the Limiting Draw Ratio (LDR).

In the LDR test, metal in the circular blank flows over the die radius and into the cup wall. The metal movement from the flat blank to the vertical sidewalls is the only metal movement which happens, since there is no metal flow within the flat bottom region.

As shown in Figure 2, the flange of the circular blank undergoes radial tension and a circumferential compression as the flange moves in a radial direction towards the circular die radius in response to a pull generated by a flat bottom punch. Blank holder pressure is set to prevent buckles in the blank.

Figure 2: Tension and compression in a drawn cup. Dashed white arrows indicate the radial tension created during cup forming; orange arrows indicate flange compression as a greater amount of metal feeds into progressively smaller regions.

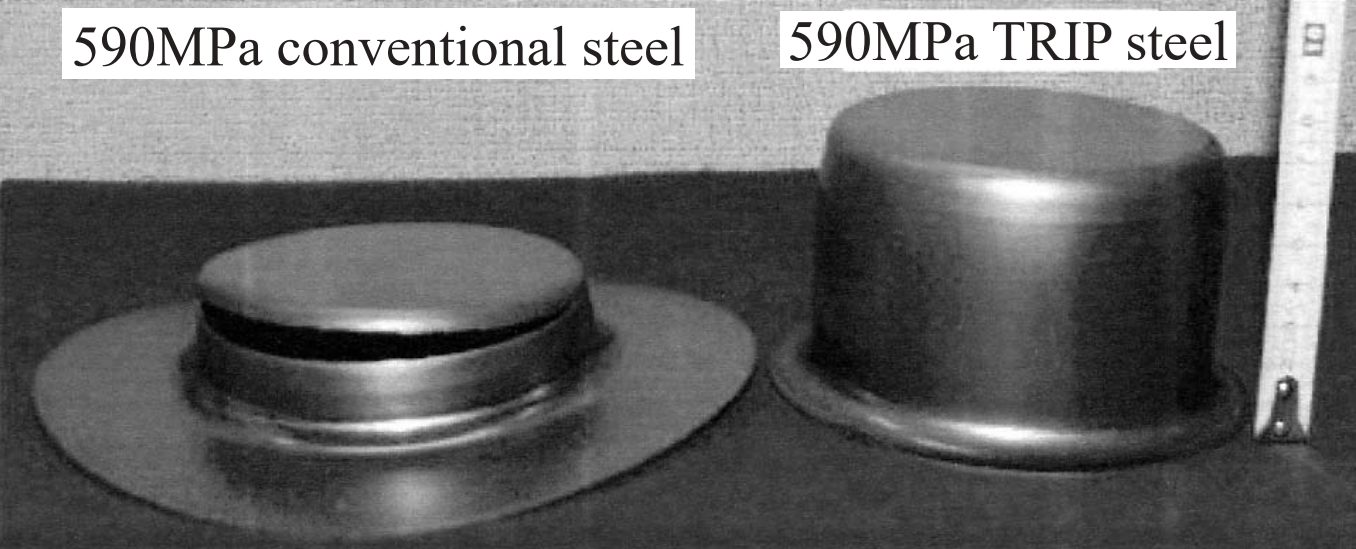

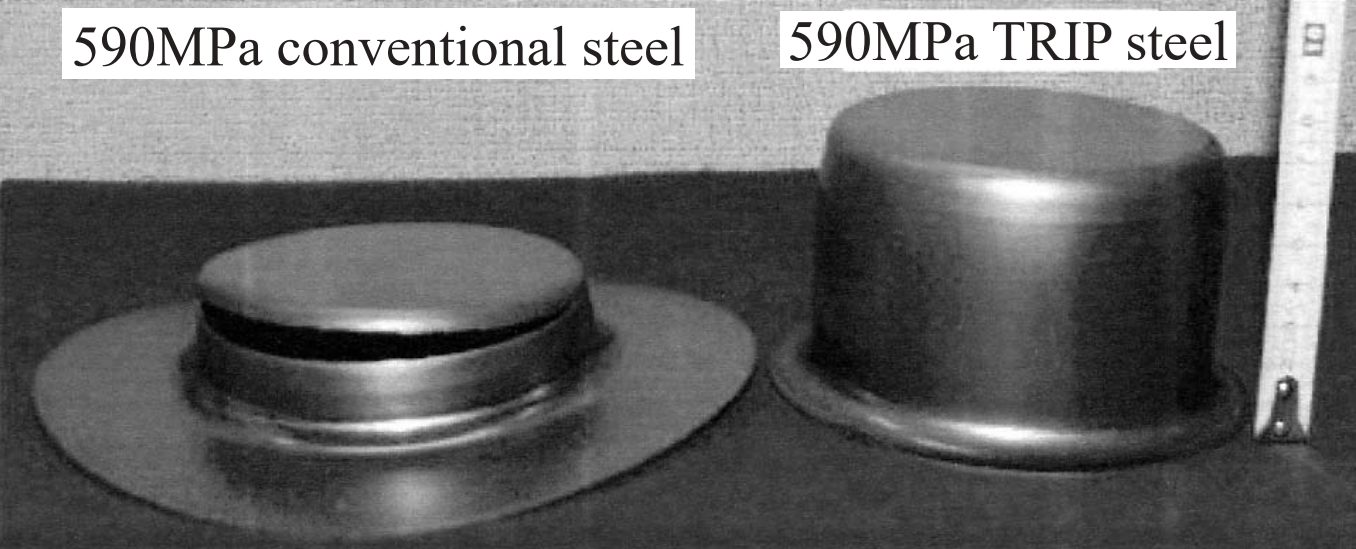

The steel property that improves cup drawing or radial drawing is the normal anisotropy or rm value. Values greater than 1 increase in the Limiting Draw Ratio. In contrast, the LDR is insensitive to the strength of the steel and the n-value. High-strength steels with UTS greater than 450 MPa and hot-rolled steels have rm values approximating one and LDR values between 2.0 – 2.2. Therefore, DP and HSLA steels have similar LDR values. However, TRIP steels have a slightly improved LDR deep drawability.T-2 Since the transformation of retained austenite to martensite is influenced by the deformation mode (Figure 3), the amount of transformed austenite to martensite generated by shrink flanging in the flange area is less than the plane strain deformation in the cup wall. This difference in transformation from retained austenite to martensite makes the wall area stronger than the flange area, thereby increasing the LDR. The benefit of the increased LDR is seen in Figure 4 which shows cups formed from different grades having the same tensile strength.

Figure 3: The cup wall in plane strain strengthens more than the shrink flange due to increased amounts of transformed martensite in TRIP steels.T-2

Figure 4: Cups formed from 590MPa tensile strength steels, highlighting greater draw depths possible with TRIP steels.T-2

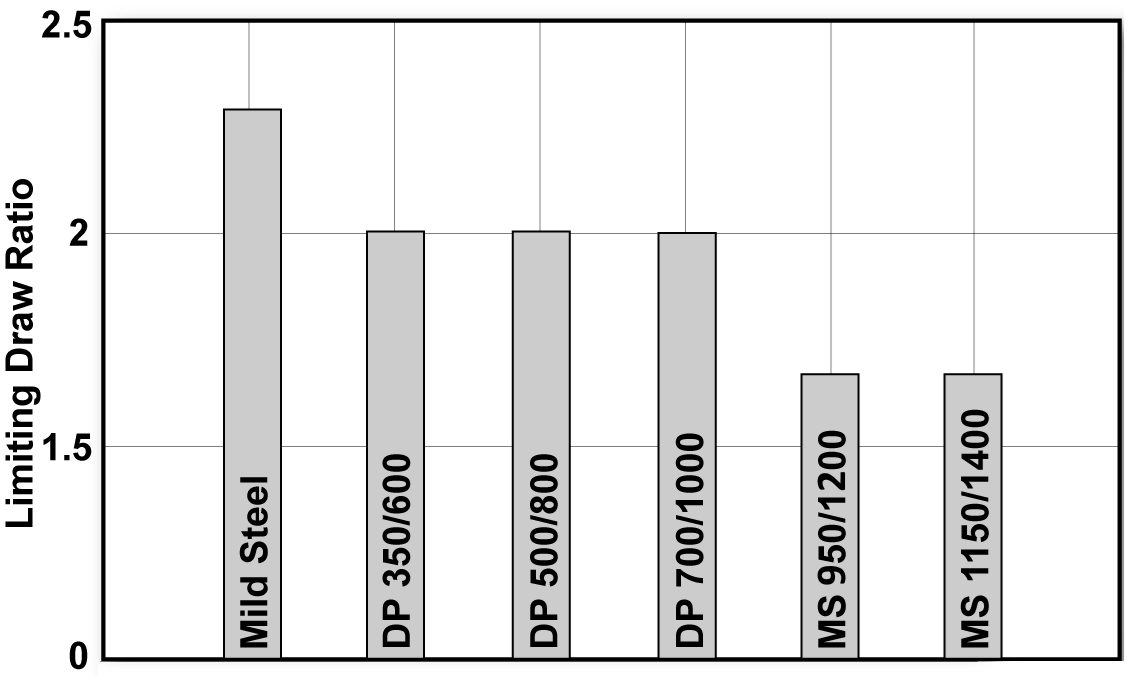

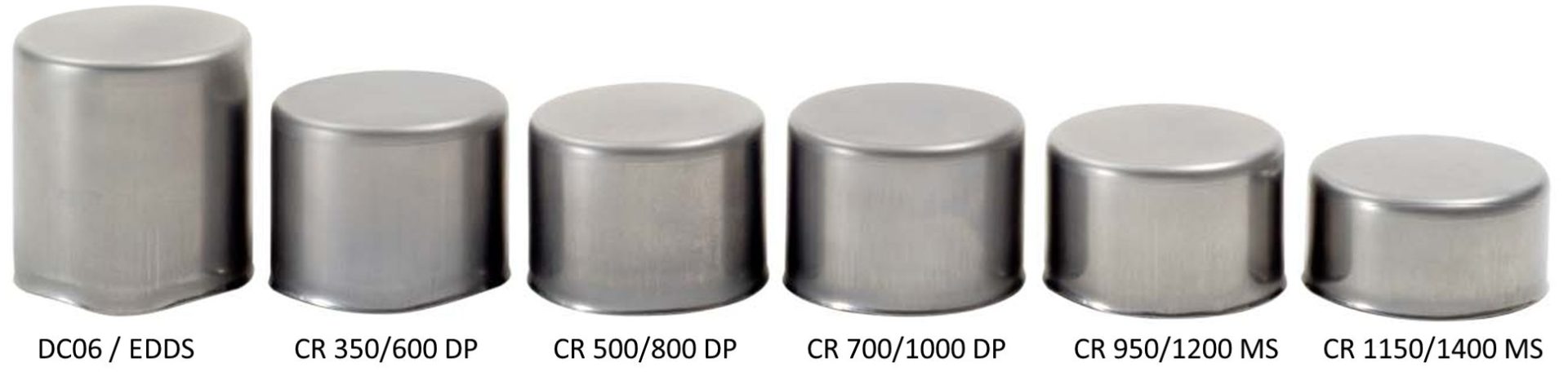

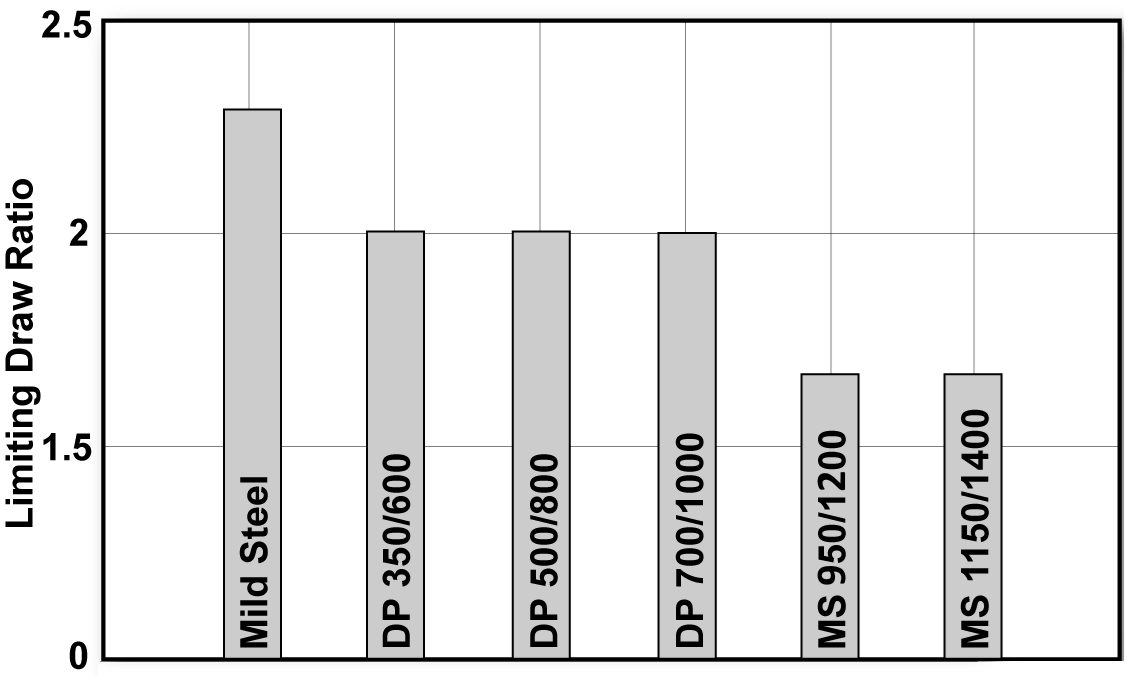

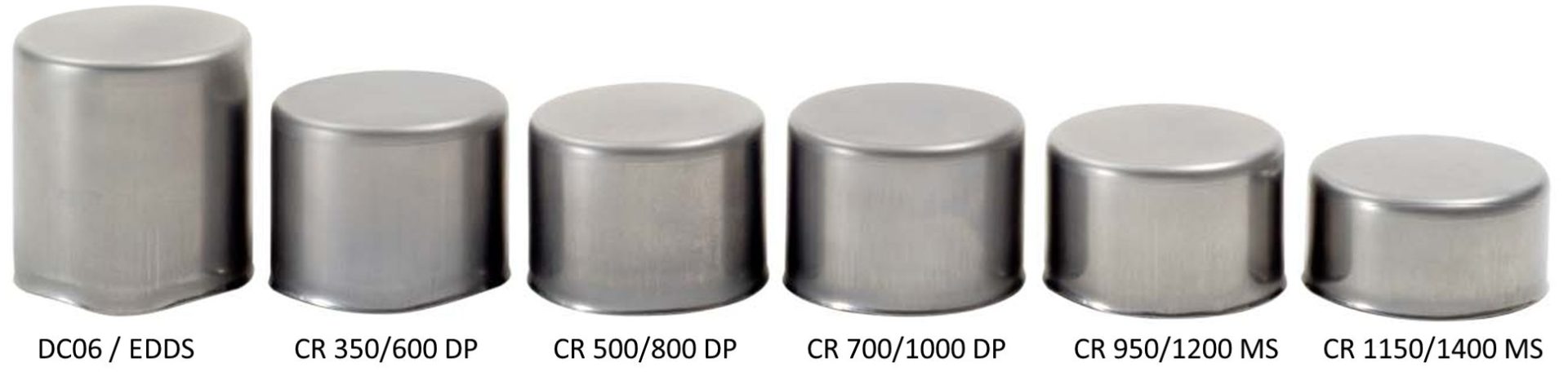

In a study of different gradesC-9, laboratory cup drawing experiments show an approximate LDR of 2.0 – 2.2 for the DP steels tested (Figure 5). Note that a doubling of the yield strength has no effect on the LDR. An increased rm value of mild steel created a small increase in LDR over DP steel. The LDR of the MS (martensitic) steel evaluated may have been impacted by the reduced bendability going over the die radius. Figure 6 shows the cup draw depths possible for the grades reported in Figure 5.S-26

Figure 5: LDR tests for Mild, DP, and MS steels.C-9

Figure 6: Cups used in the testing reported in Figure 5.S-26

Even though r-value is the only steel property influencing the formability of drawn flat-bottom cups through its relationship with LDR, not all cups have flat bottoms. Some have hemispherical or other configurations for bottoms. Adding a dome-like shape to the cup results in a more complex forming operation which is now sensitive to material properties like n-value and microstructures.

Corners of box-shaped stampings and the ends of closed channels contain design features similar to drawn cups, providing insight on an analytical approach.

- The four corners of a box-shaped drawn panel should each be analyzed as one-quarter of a cup. Buckles forming in the binder area indicate compressive flow. The corners of the blank will form the same as a deep drawn cup.

- The side walls are formed by metal flowing from the binder across the die radius. The term for this metal flow is bend-and-straighten.

In summary, higher LDR values are achievable in steels with greater values of the normal anisotropy ratio, rm. The absolute value of the LDR, however, also depends on the lubrication, blank holder load, die radius and other system inputs. Figure 7 compares a higher viscosity lubricant on the left with a lower viscosity lubricant on the right.S-26 Die radii need to be balanced: large radii promotes metal flow and may lead to wrinkles, while small radii restricts metal flow and may lead to splits.

Figure 7: The influence of lubricant viscosity on drawing. The cup formed with the higher viscosity lubricant is on the left.S-26

![Non-Linear Strain Paths (Stress-Based FLCs)]()

Coatings

Friction during the stamping process is a key variable which impacts metal flow. It varies across the stamping based on local conditions like geometry, pressure, and lubrication, which change during the forming process. The tool surface influences metal flow, as seen when comparing the results of uncoated tools to those with chrome plating or PVD coatings.

The sheet steel surface is another contributor to friction and metal flow, which changes based on the type of galvanized coating. There are different types of friction tests which attempt to replicate different portions of the forming process, such as flow through draw beads of drawing under tension. Since these tests measure friction under different conditions, the numerical results for the coefficient of friction are not directly comparable. However, within a specific test, extracting useful information is possible.

A study S-54 evaluated the friction of seven deep-drawing steels (DDS), all between 0.77mm and 0.84 mm, with the coating being the most significant difference between the products. Table 1 shows the sample identification and lists the mechanical and coating properties of the tested products, which included two electrogalvanized (EG), one electrogalvanized Zn-Fe alloy (EGA), two hot dip galvanized (HDGI), and two hot dip galvanneal (HDGA) steels. The HDGA coatings differed in the percentage of zeta phase relative to delta phase in the coatings.

Table 1: Properties of DDS grades used in this friction study.S-54

Tests to evaluate friction included a Draw Bead Simulator (DBS), a Bending Under Tension (BUT) test, and a Stretch Forming Simulator (SFS) test. Dome height test and deep draw cup tests were performed to verify the friction behavior of the tested materials. Citation S-54 explains these tests in greater detail. Two different lubrication conditions were evaluated: “as” meaning as-received, and “lub” where the samples were initially cleaned with acetone and mill oil was reapplied.

Figure 1 summarizes the results from the three different friction tests. The relative performance of different coatings is consistent across the tests.S-54 For the tested materials, the HDGI coated steels showed the lowest average friction coefficient and a more stable friction behavior regardless of the lubrication conditions. Zn-Fe alloy coatings (EGA or HDGA) typically resulted in the highest friction. The BUT test generates the lowest strain level among three tests, while the DBS and SFS tests result in higher strain due to a more severe surface contact between tooling and specimen. Stretch forming test tends to result a lower friction coefficient mainly due to higher strain in the stretching process.

Figure 1: Friction test results for different coatings. The relative performance of different coatings is consistent across the tests. S-54

Coating and lubrication interact to influence friction. Draw bead simulator testing compared friction generated on 1mm cold rolled (bare), hot dip galvanized (HDG), and electrogalvanized (EG) deep drawing steel, lubricated with varying amounts of either mill oil, prelube, or a combination of the lubricantsS-68, as summarized in Figures 2, 3, and 4.

Conclusions from this study include:

- Prelube reduces friction on all tested surfaces, with the most dramatic effect seen on electrogalvanized surfaces.

- Above 1 g/m2, there is little friction benefit associated with adding additional lubrication.

- Adding heavier amounts of prelube on top of mill oil did incrementally reduce friction, but the effect essentially maximized at 1.5 g/m2 prelube on top of 1 g/m2 mill oil.

- Cold rolled (bare) steel showed a greater tolerance for dry spots than hot dip or electrogalvanized surfaces. Areas without any lubricant on HDG or EG surfaces led to sample fracture.

Figure 2: DBS Coefficient of Friction: Cold Rolled (Bare) Mild Steel.S-68

Figure 3: DBS Coefficient of Friction: Hot Dip Galvanized Mild Steel.S-68

Figure 4: DBS Coefficient of Friction: Electrogalvanized Mild Steel.S-68

The tool material influences metal flow and therefore friction, but its effect varies with the zinc coating on the sheet steel. The impact of tool steel, kirksite zinc, cast iron, cast steel and chrome plated cast iron on different coated deep drawing steels was evaluated using the Bending Under Tension test.S-55 The friction coefficient obtained using kirksite is lower than that obtained with the other die materials and is relatively independent of the type of zinc coating (Figure 5), reinforcing the caution usually applied stating that soft tool tryout will not be fully representative of what occurs later in the die development process. Supporting the conclusions of the prior study, this evaluation also showed that the HDGI coating tends to have the lowest friction coefficient, especially for cast iron with and without chrome plating (hard tool and production). Also observed was that an oil-based blankwash solution tends to have the highest friction coefficient among the tested lubricants, while a dry film has the lowest friction coefficient.

Figure 5: Influence of die material on friction of galvanized DDS determined in the Bending Under Tension test.S-55

The surface phase in hot dipped galvannealed steel has a impact on friction. Whereas the surface of hot dip galvanized steel is essentially pure zinc, the GA surface may be zeta phase or delta phase. The iron content is the primary compositional difference: the zeta (ζ) phase contains approximately 5.2% to 6.1% by weight of iron, and the delta (δ) phase contains approximately 7.0% to 11.5% by weight of iron.G-21 Zeta phase is softer and less brittle than the delta phase, but has a high coefficient of friction.G-22 Even with a fully delta phase surface, additional optimization is possible to produce targeted surface morphologies.S-56 The two right-most images in Figure 6 are both of delta phase surfaces, with the cubic surface (right image) associated with better formability than the rod surface of the center image (Figures 7 and 8).

Figure 6: Surface morphology and coating cross section of 3 galvanneal coatings. Left: Zeta surface; Center: Delta-rod surface; Right: Delta-cubic surface.S-56

Figure 7: Formability of galvannealed surfaces evaluated through a square cup test.S-56

Figure 8: Formability of galvannealed surfaces evaluated through a Limiting Draw Height (LDH) test. Higher is better.S-56

Low annealing temperature or time can result in excessive zeta phase. However, longer and hotter annealing cycles increase the risk of powdering and flaking. Producing the correct balance of ZnFe phases requires control of time and temperature of the galvannealing process.

![Figure 5: As-generated FLCs compared with FLCs after strain path, curvature, and tool contact pressure corrections [References 1 and 3]](https://ahssinsights.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/2.3.3.2_5.jpg)