S-110

Citation:

S-110. T.B. Stoughton, “The DIC Revolution in Metal Property Characterization“, Presented at 2021 Great Designs in Steel, Sponsored by American Iron and Steel Institute.

S-110. T.B. Stoughton, “The DIC Revolution in Metal Property Characterization“, Presented at 2021 Great Designs in Steel, Sponsored by American Iron and Steel Institute.

Z-15. D.J. Zhou, and K. Kannan, “The Effect of Combination Beads on Springback: Experimental Study & Virtual Study“, Presented at 2021 Great Designs in Steel, Sponsored by American Iron and Steel Institute.

Z-14. M. Zoernack, “New Advancements of Cold Forming TRB® AHSS,” Presented at 2021 Great Designs in Steel, Sponsored by American Iron and Steel Institute.

AHSS products have significantly different forming characteristics and these challenge conventional mechanical and hydraulic presses. The dramatically higher strength of these new steels result in higher forming loads and increased springback. Higher contact pressures cause higher temperatures at the die-steel interface, requiring high performance lubricants and tool steel inserts with advanced coatings. Although the decrease in ductility is not as severe as seen with HSLA grades of a similar strength level, there is a reduction in formability. Further complicating matters is that in addition to traditional stamping failures due to necking when the part strains exceed the forming limit curve, AHSS grades have additional failure modes such as reduced bendability and cut edge ductility (collectively called local formability failure modes) which are not predicted using current analytical techniques.

These challenges lead to issues with the precision of part formation and stamping line productivity. The stamping industry is developing more advanced die designs as well as advanced manufacturing techniques to help reduce fractures and scrap associated with AHSS stamped on traditional presses. Using a servo-driven press is one approach to address the challenges of forming and cutting AHSS grades. Recent growth in the use of servo presses in the automotive manufacturing industry parallels the increased use of AHSS in the body structure of new automobiles.

A servo press uses a servomotor as the drive source. Servo press systems are more flexible than flywheel-driven presses and are both faster and more accurate than hydraulic presses. A servomotor allows for control of the position, direction, and speed of the output shaft in contrast to a constant cycle speed of flywheel driven presses, for example. New forming techniques take advantage of this flexibility, achieving more complex part geometries while maintaining dimensional precision.

Mechanical presses are powered by an electric motor that drives a large flywheel. The flywheel stores kinetic energy, which is released through various drive types like cranks, knuckle joints, and linkages. Powering hydraulic presses are electric motors which drive hydraulic cylinders to move the ram up or down.

Servo-driven presses can be either mechanical or hydraulic. In servo-mechanical presses, the high-powered servo motor allows for direct driving of the mechanical press without using a flywheel and clutch. Up to the rated speed, maximum torque is available. Beyond this rated speed, the available torque decreases until reaching the maximum speed. If forming speeds remain below this rated speed, servo presses may have an advantage over flywheel driven presses since full tonnage is available even at lower strokes per minute. This is a useful feature if heat build-up limits how fast the part is capable of running.

Traditional hydraulic presses use variable volume pumps powered by constant velocity electric motors. Servo-hydraulic presses either combine conventional electric motors with servo (proportional) valves or pair servo motors with simple pumps and valves. Typically, servo-hydraulic presses reach higher slide speeds than conventional hydraulic presses, but usually are not faster than servo-mechanical presses over a complete cycle. Due to this advantage, most automotive stampers use servo-mechanical presses.

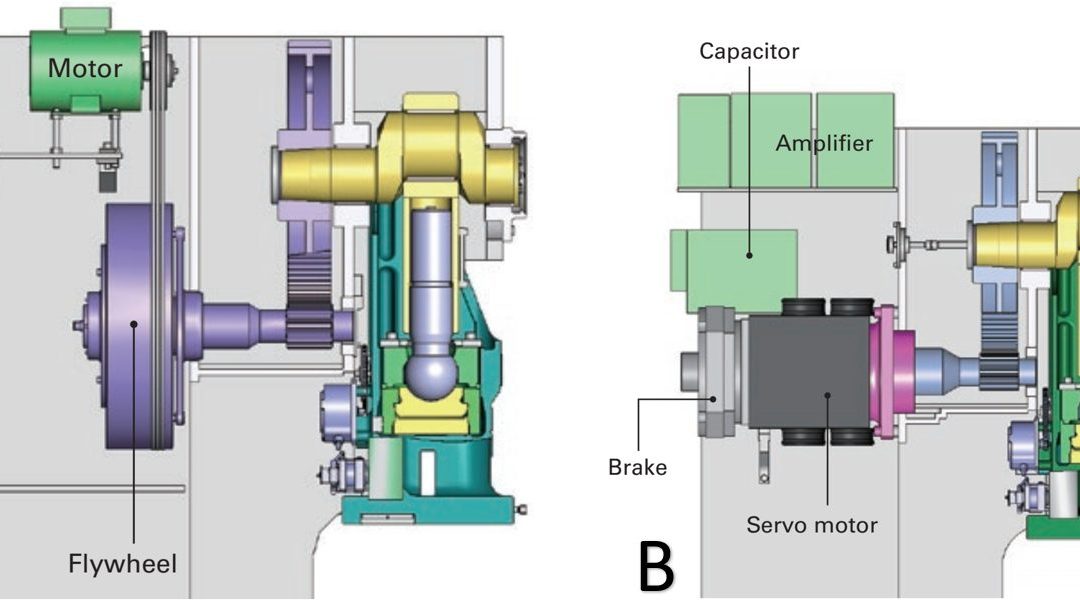

For both servo-mechanical and servo-hydraulic presses, the other press components remain the same as conventional presses. Figure 1 compares pertinent elements of a flywheel-driven mechanical press with one driven by a servo motor.

Figure 1: Drive components in a mechanical press. A) Flywheel driven; B) Servo motor driven.A-9

Servo press technology has many advantages compared to flywheel-driven mechanical presses when working with AHSS materials. Press manufacturers and users claim advantages in stroke, speed, energy usage, quality, tool life and uptime; these of course are dependent upon part shape and forming complexity. Figure 2 shows the difference between the available motions of flywheel-driven mechanical presses verses servo driven mechanical presses. The slide motion of the servo press can be programmed for more parts per minute, decreased drawing speed to reduce quality errors, or dwelling or re-striking at bottom dead center to reduce springback.

Figure 2: Comparison of Press Signatures in Fixed Motion Mechanical Presses and Free-Motion Servo-Driven Presses.M-3

Some examples highlighting the flexibility of servo press motions include:

Figure 3: Cycle rates for servo-driven and flywheel-driven mechanical presses.B-9

Figure 4 illustrates power storage and output in a servo-mechanical press system over the course of a cycle. In this example, the press operates with two main motors, each having a maximum output of 175 kW. An external energy device stores energy from the slide deceleration, and is tapped when the press motion requires more than 175 kW from each motor. The stored energy (maximum of 350 kW combined in the two 175 kW motors) is available during peak power requirements, enabling the facility power load to remain nearly constant at around 50 kW.B-9

Figure 4: Power storage and output in a servo mechanical press system.B-9

Categorizing both mechanical and hydraulic presses requires three different capacities or ratings – force, energy, and power. Historically, when making parts out of mild steel or even some HSLA steels, using the old rules-of-thumb to estimate forming loads was sufficient. Once the tonnage requirements and some processing requirements were known, stamping could occur in whichever press met those minimum tonnage and bed size requirements.

In these cases, press capacity (for example, 1000 kN) is a suitable number for the mechanical characteristics of a stamping press. Capacity, or tonnage rating, indicates the maximum force that the press can apply without damaging its components, like the machine frame, slide-adjusting mechanisms, pitman (connection rods) or main gear bushings.

A servo press transmits force (not energy) the same way as the equivalent conventional press (mechanical or hydraulic). However, the amount of force available throughout the stroke depends on whether the press is hydraulic or mechanically driven. Hydraulic presses can exert maximum force during the entire stroke as tonnage generation occurs via hydraulic fluid, pumps, and cylinders. Mechanical presses exert their maximum force at a specific distance above bottom dead center (BDC), usually defined at 0.5 inch. At increased distances above bottom dead center, the loss of mechanical advantage reduces the tonnage available for the press to apply. This phenomenon is known as de-rated tonnage, and it applies to conventional mechanical presses as well as servo-mechanical presses. Figure 5 shows a typical press-force curve for a 600-ton mechanical press. In this example, when the press is approximately 3 inches off BDC, the maximum tonnage available is only 250 tons – significantly less than the 600-ton rating.

Figure 5: The Press-Force curve shows the maximum tonnage a mechanical press can apply based on the position of the slide relative to the bottom dead center reference distance. This de-rated tonnage applies to both conventional mechanical presses as well as servo-mechanical presses.E-2

Press energy reflects the ability to provide that force over a specified distance (draw depth) at a given cycle rate. Figure 6 shows a typical press-energy curve for the same 600-ton mechanical press. The energy available depends on the size and speed of the flywheel, as well as the size of the main drive motor. As the flywheel rotates faster, the amount of stored energy increases, reflected in the first portion of the curve. The cutting or forming process consumes energy, which the drive motor must replenish during the nonworking part of the stroke. At faster speeds, the motor has less time to restore the energy. If the energy cannot be restored in time, the press stalls. The graph illustrates how the available energy of the press diminishes to 25% of the rated capacity when accompanied by a speed reduction from 24 strokes per minute to 12 strokes per minute.

Figure 6: A representative press-energy curve for a 600 ton mechanical press. Reducing the stroke rate from 24 to 12 reduces available energy by 75%.E-2

Rules of thumb are useful to estimate press loads. However, a better evaluation of draw force, embossment force, and blank holding force comes from simulation tools. Many programs enable the user to specify all of the system inputs. This is especially important when forming AHSS because the rapid work hardening seen in these grades has a major effect on the press loads. In addition, instead of using a simple restraining force on blank movement, incorporating the geometry and effects of the actual draw beads leads to improved simulation accuracy.

A common shortcut taken in simulation is the assumption that the tools are rigid during forming. In practice, however, tools will deform elastically. Further increasing this deflection of the dies (sometimes called breathing) is the higher work hardening of AHSS grades. This discrepancy leads to a significant increase in the determined press loads, especially when the punch is at home position. Hence, for a given part, the draw depth used for the determination of the calculated press load is an important parameter. Applying the nominal draw depth may result in an over-estimation of press loads. Similarly, assuming that the structure, platens, bolsters, and other components of the press are completely rigid may lead to variation in press loads, especially after moving the physical tooling from one press to another.

In all cases, validation of all simulation predictions is good practice. Every simulation contains assumptions, with some being more critical than others. Use practical stamping tests to determine the optimum parameter settings for the simulation. Quick items to confirm simulation matches with reality include draw-in amounts (lay draw panel on top of blank) and press tonnages (check load monitors). When physical panels match simulation results, confidence in the simulation accuracy rises.

In processes like restrike operations, simulation may not accurately estimate press loads. In these cases, run “what-if” simulations to observe forming trends for a given part, which helps to develop a more favorable forming-process design.

Air cushions and nitrogen cylinders are common on single action mechanical presses to give them a double action. There is a tonnage spike on initial contact with the blankholder and setting of the draw beads, occurring while the press is still several inches off Bottom Dead Center. This spike increases the likelihood of a mechanical press being damaged. Figure 7 shows the potential negative consequences when a mechanical press exceeds the rated capacity of the press and the associated components.

Figure 7: Broken connecting rod on a mechanical press.M-5

A nitrogen die cushion in a single-acting press needs to apply considerable force to set draw beads in AHSS sheets before drawing begins, as well as to apply stake beads at the end of the stroke for springback control. In some cases, binder separation may occur because of insufficient cushion tonnage, resulting in a loss of control for the stamping process and excessive wrinkling of the part or addendum. The high impact load on the cushion may occur several inches up from the bottom of the press stroke, where de-rated tonnage means a reduced maximum load to avoid press damage. Flywheel-driven mechanical presses are susceptible to damage due to these shock loads, since the impact point in the stroke occurs when the press is travelling at a higher velocity. The high shock loads dissipate additional flywheel energy well above bottom dead center of the stroke. Therefore, a nitrogen-die cushion may be inadequate for optimum pressure and process control when working with AHSS.

Staggering the heights of the nitrogen cylinders so they do not all engage at the same time is one way to reduce the shock load (Figure 8). A double-action press will set the draw beads when the outer slide approaches bottom dead center where the full tonnage rating is available and where the slide velocity is substantially lower. This minimizes any shock loads on the die and press with resultant load spikes less likely to exceed the rated press capacity.

Figure 8: Staggered nitrogen cylinders reduce the initial shock load when setting draw beads by engaging at different depths in the press stroke.M-5

The increased forces needed to form, cut and trim higher-strength steels create significant challenges for pressroom equipment and tooling. These include excessive tooling deflections, damaging tipping-moments, and amplified vibrations and snapthrough forces that can shock and break dies—and sometimes presses. Stamping AHSS materials can affect the size, strength, power and overall configuration of every major piece of the press line, including material-handling equipment, coil straighteners, feed systems and presses.

Here is what every stamper should know about higher-strength materials:

As steels becomes stronger, a corresponding increase in process knowledge is required in terms of die design, construction and maintenance, and equipment selection.

In a flywheel-driven mechanical press, the size of the main motor, flywheel mass, and rotation speed of the flywheel become critical. The main motor, along with its electrical connections, is the only source of energy for the press and it must have sufficient power to supply the demands of the stamping operation. As the flywheel is an energy storage device, it must be able to store and deliver the required energy when needed. The stored energy varies by the square of the speed; thus, flywheels can store a large amount of energy when the press is running at full speed. If heat generation and forming problems occur when stamping AHSS grades, operators may be inclined to slow down press speeds. However, this slowdown may lead to not meeting the energy requirements to form the part, ultimately resulting in the press stalling.

Take the example of a part with a draw depth of 2 inches. If stamped from HSLA 350/450, it may need 150 tons of forming force, for a total of 300 inch-tons of forming energy (2 inches times 150 tons). On this press, 14 strokes per minute is sufficient to generate enough forming energy, as indicated by the green dot in Figure 9.

Studies have shown that the forming tonnage of DP steels may be twice that of HSLA steels, which means that the 2 inch draw depth could need 300 tons of forming force, for a total of 600 inch-tons of forming energy. The red dot in Figure 9 shows that our press must run at 20 strokes per minute to ensure that there is sufficient forming energy. The speed is well within the capability of the press, but our strategy of running faster may not be appropriate for forming AHSS grades where heat generation could result in lubricant breakdown leading to die wear, galling, and scoring. Running the press slower to avoid these concerns increases the risk of stalling.

Figure 9: Higher strength materials requiring increased forming energy also require faster cycle times. If the greater cycle time cannot be maintained due to reasons like heat buildup or lubricant breakdown, a flywheel-driven press may stall.E-2

Predicting the press forces needed initially to form a part is known from a basic understanding of sheet metal forming. Different methods are available to calculate drawing force, ram force, slide force, or blankholder force. The press load signature is an output from most forming-process development simulation programs, as well as special press load monitors.

Most structural components include design features to improve local stiffness. Typically, forming of the features requiring embossing processes occurs near the end of the stroke near Bottom Dead Center. Predicting forces needed for such a process is usually based on press shop experiences applicable to conventional steel grades. To generate comparable numbers for AHSS grades, forming process simulation is recommended.

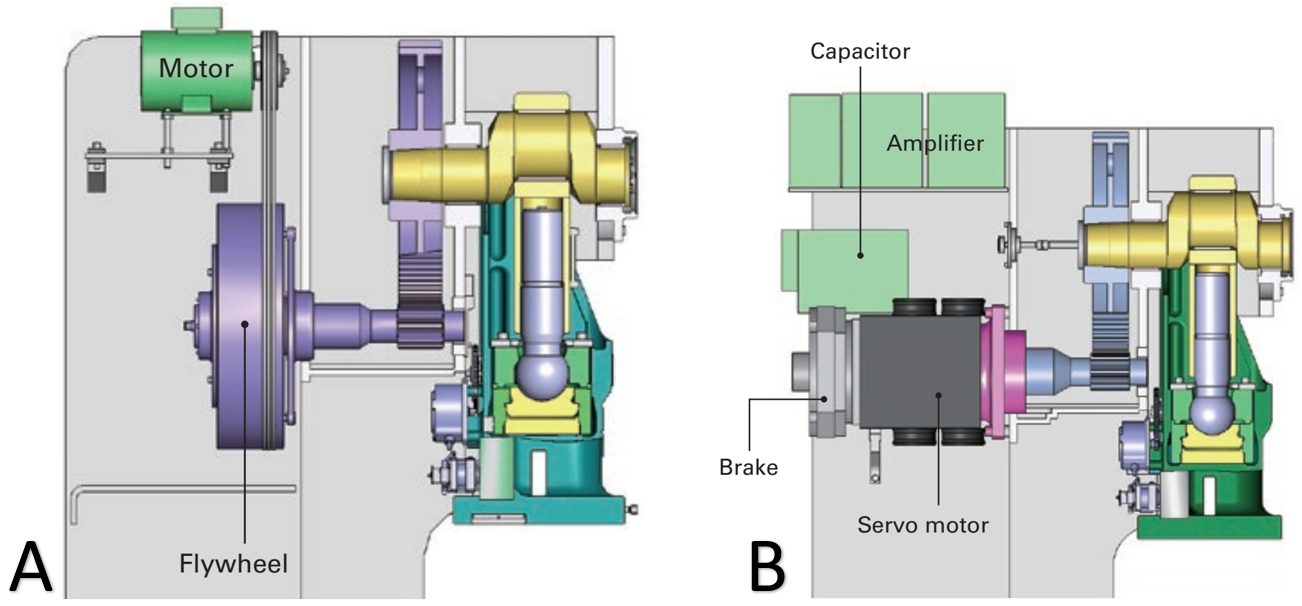

In Citation H-3, stamping simulations evaluated the forming of a cross member having a hat-profile with an embossment formed at the end of the stroke (Figure 10). The study simulated press forces and press energy involved for drawing and embossing a channel section from four steel grades approximately 1.5 mm thick: mild steel, HSLA 250/350, HSLA 350/450, and DP 350/600. Figures 11A and 11B clearly show that the embossing phase rather than the drawing phase dominates the total force and energy requirements, even though the punch travel for embossing is only a fraction of the drawing depth.

Figure 10: Cross section of a component having a longitudinal embossment to improve local stiffness.H-3

Figure 11: Embossing requires significantly more (A) force and (B) energy than drawing, even though the punch travel in the embossing stage is much smaller.H-3

Figures 12 and 13 highlight the press energy requirements, showing the greater energy required for higher strength steels. The embossment starts to form at a punch displacement of 85 mm, indicated by the three dots in Figure 12. The last increment of punch travel to 98 mm requires significantly higher energy, as shown in Figure 13. Note that compared with mild steel, the dual phase steel grade requires significantly more energy to form the part to home with the 98 mm travel.

Figure 12: Energy needed to form the component increases for higher strength steel grades. Forming the embossment begins at 85 mm of punch travel, indicated by the 3 dots.H-3

Figure 13: Additional energy required to form the embossment increases for higher strength steel grades.H-3

It is not only embossments that require substantially more force and energy at the end of the stroke. Stake beads for springback control engage late in the stroke to provide sidewall stretch. Depending on the design of the forming process, the steel into which the stake beads engage may have passed through conventional draw beads for metal flow control, and therefore are work-hardened to an even higher strength. This leads to greater requirements for die closing force and energy. Certain draw-bead geometries which demand different closing conditions around the periphery of the stamping also may influence closing force and energy requirements.

Using existing production data can estimate press loads for simple geometries, knowing just the thickness and tensile strength. There is a proportional increase in forming load (F) resulting from the product of thickness (t) and tensile strength (Rm). For example, in your current production (1), you know your drawing force F1, and the thickness t1 and tensile strength Rm1 of the steel you are forming. You are switching production (2) to a new tensile strength Rm2 and thickness t2, and you want to know the drawing force F2. Set up the following equation:

The work in Citation T-11 studied the press loads required to form a cross member with a simple hat profile from two steels of the same 0.7 mm thickness: HSLA 350/450 and DP 300/500 steels. Here, it was known that an HSLA coil with 433 MPa tensile strength required 791 kN of drawing force. Of interest was the drawing force required to stamp a dual phase steel with a tensile strength of 522 MPa. Using the equations above, the estimated force F2 was calculated as 954MPa:

![]()

This estimated 954 MPa compares favorably with the force measured during their trial stamping of 934 MPa. Using this technique typically is sufficient to estimate the press requirements, but may lead to an over-estimation of the actual loads.

The energy required for plastically deforming a material (force times distance) has the same units as the area under the true stress-true strain curve. For this reason, assessing the forming energy requirements of two grades requires comparing the respective areas under their true stress – true strain curves. The shape and magnitude of these curves are a function of the yield strength and work hardening behavior as characterized by the n-value. At the same yield strength, a grade with higher n-value will require greater press energy capability, as highlighted in Figure 14 which compares HSLA 350/450 and DP 350/600. For these specific tensile test results, there is approximately 30% greater area under the DP curve compared with the HSLA curve, suggesting that forming the DP grade requires 30% more energy than required to form a part from the HSLA grade.

Figure 14: True stress-strain curves for two materials with equal yield strength.T-11

Greater work hardening of DP steels results in higher forming tonnage requirements when compared to HSLA grades at the same incoming yield strength and sheet thickness. However, AHSS applications justify a thickness reduction, and along with this is a reduction in the required press load. The required power is a function of applied forces, the displacement of the moving parts, and the speed. The energy rating of a press is also a function of applied press load and the distance over which the load is applied. For example, pushing 200 tons through 3 inches of deep drawing requires 600 inch–tons of energy. Changing the part to AHSS could require 500 tons of force working through the same 3 inch distance, requiring 1500 inch-tons of energy. Each stroke of the press expends a given amount of energy, all of which must be replaced before the next stroke begins.

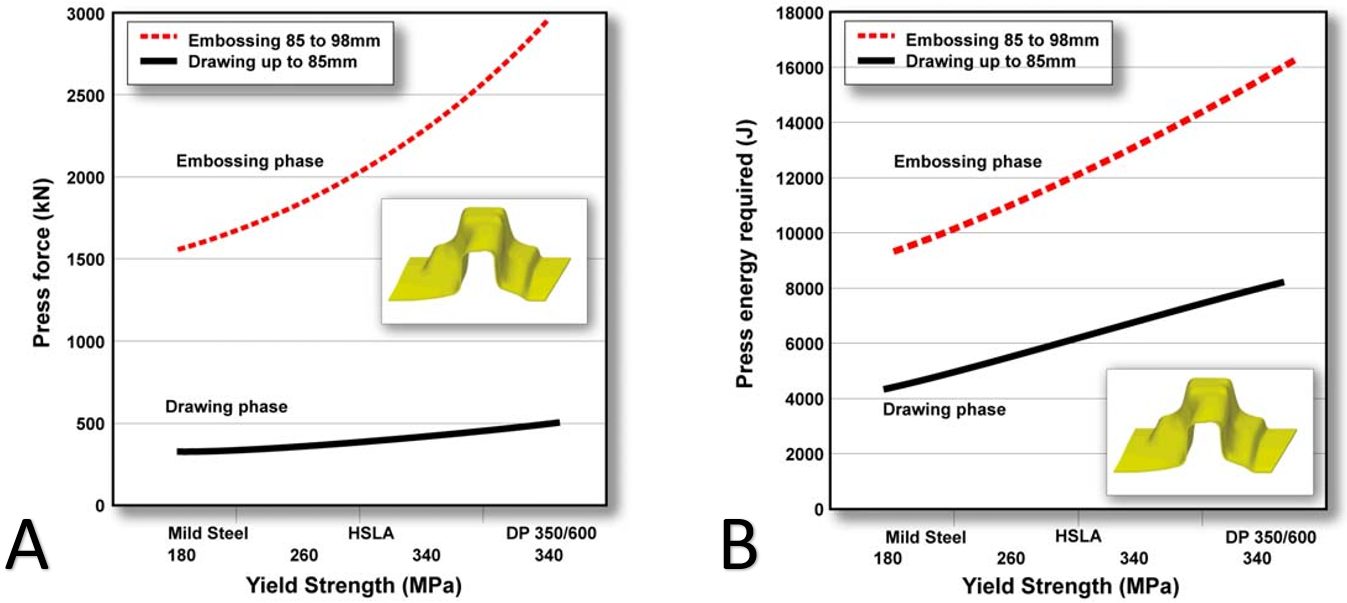

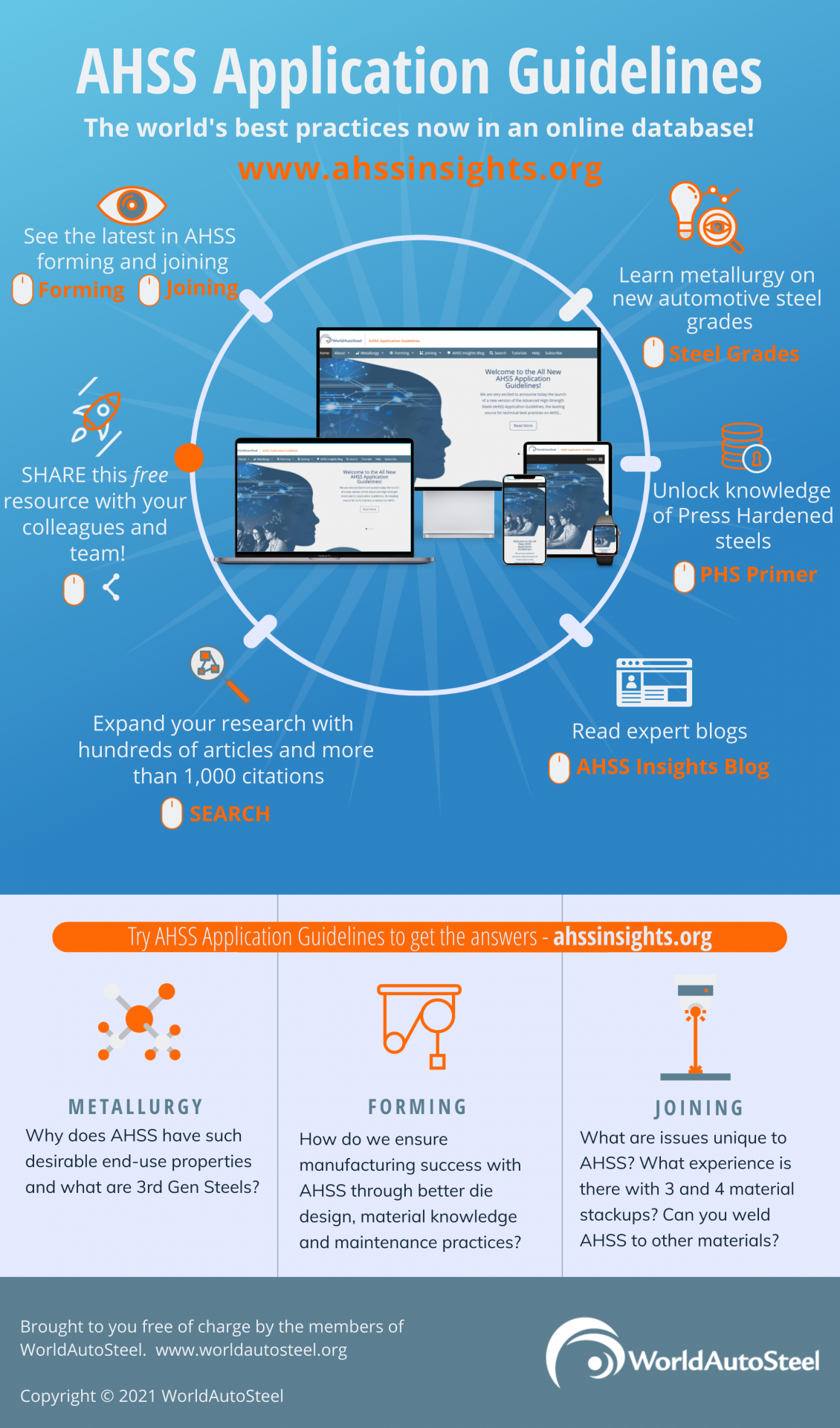

The leading source for technical best practices on the forming and joining of Advanced High-Strength Steels (AHSS) for vehicle manufacture is released today by WorldAutoSteel, the automotive group of the World Steel Association. The AHSS Application Guidelines Version 7.0 is now online at ahssinsights.org in a searchable database, allowing users to pinpoint information critical to successful use of these amazingly capable steels. WorldAutoSteel members make these Guidelines freely available for use to the world’s automotive community.

The leading source for technical best practices on the forming and joining of Advanced High-Strength Steels (AHSS) for vehicle manufacture is released today by WorldAutoSteel, the automotive group of the World Steel Association. The AHSS Application Guidelines Version 7.0 is now online at ahssinsights.org in a searchable database, allowing users to pinpoint information critical to successful use of these amazingly capable steels. WorldAutoSteel members make these Guidelines freely available for use to the world’s automotive community.

“More and more automakers are turning to AHSS to balance the needs for crashworthiness, lighter weight and lower emissions, while still manufacturing cars that are affordable,” says George Coates, Technical Director, WorldAutoSteel. “The AHSS Application Guidelines provides critical knowledge that will help users adapt their manufacturing environment to these evolving steels and understand processes and technologies that lead to efficient vehicle structures.” AHSS constitute as much as 70 percent of the steel content in vehicle structures today, according to automaker reports.

New grades of steel that are profiled in Version 7.0 show dramatically increased strength while achieving breakthrough formability, enabling applications and geometries that previously were not attainable.

“Steel’s low primary production emissions, now coupled with efficient fabrication methods, as well as a strong global recycling and reuse infrastructure all create a solid foundation upon which to pursue vehicle carbon neutrality,” notes Cees ten Broek, Director, WorldAutoSteel. “These Guidelines contain knowledge gleaned from global research and experience, including significant investment of our members who are the designers and manufacturers of these steels.”

Editors and Authors Dr. Daniel Schaeffler, President Engineering Quality Solutions, Inc., for Metallurgy and Forming, and Menachem Kimchi, M.Sc., Assistant Professor – Practice, Materials Science and Engineering, Ohio State University, have drawn from the insights of WorldAutoSteel members companies, automotive OEMs and suppliers, and leading steel researchers and application experts. Together with their own research and field experience, the technical team have refreshed existing data and added a wealth of new information in this updated version.

The new database includes a host of new resources for automotive engineers, design and manufacturing personnel and students of automotive manufacturing, including:

The new online format enables consistent annual updates as new mastery of AHSS’s unique microstructures is gained, new technology and grades are developed, and data is gathered. Be sure to subscribe to receive regular updates and blogs that represent a world of experience as the database evolves.

You’re right where you need to be to start exploring the database. Click Tutorials from the top menu to get a tour on how the site works so you can make the best of your experience. Come back often–we’re available 24/7 anywhere in the world, no download needed!